The Guinea worm is inching ever closer to extinction, but unlike just about every other endangered species, no one is going to try to save it, least of all scientists. On the contrary, the worm’s disappearance would mark the scouring of a disease from the face of the earth—a feat humanity’s only been able to celebrate twice before, with the end of smallpox in 1980 and of the cattle disease rinderpest in 2011. (Polio, despite the fact that a vaccine’s been around for more than half a century, has managed to hang on by its microscopic threads.)

What Is Guinea Worm Disease?

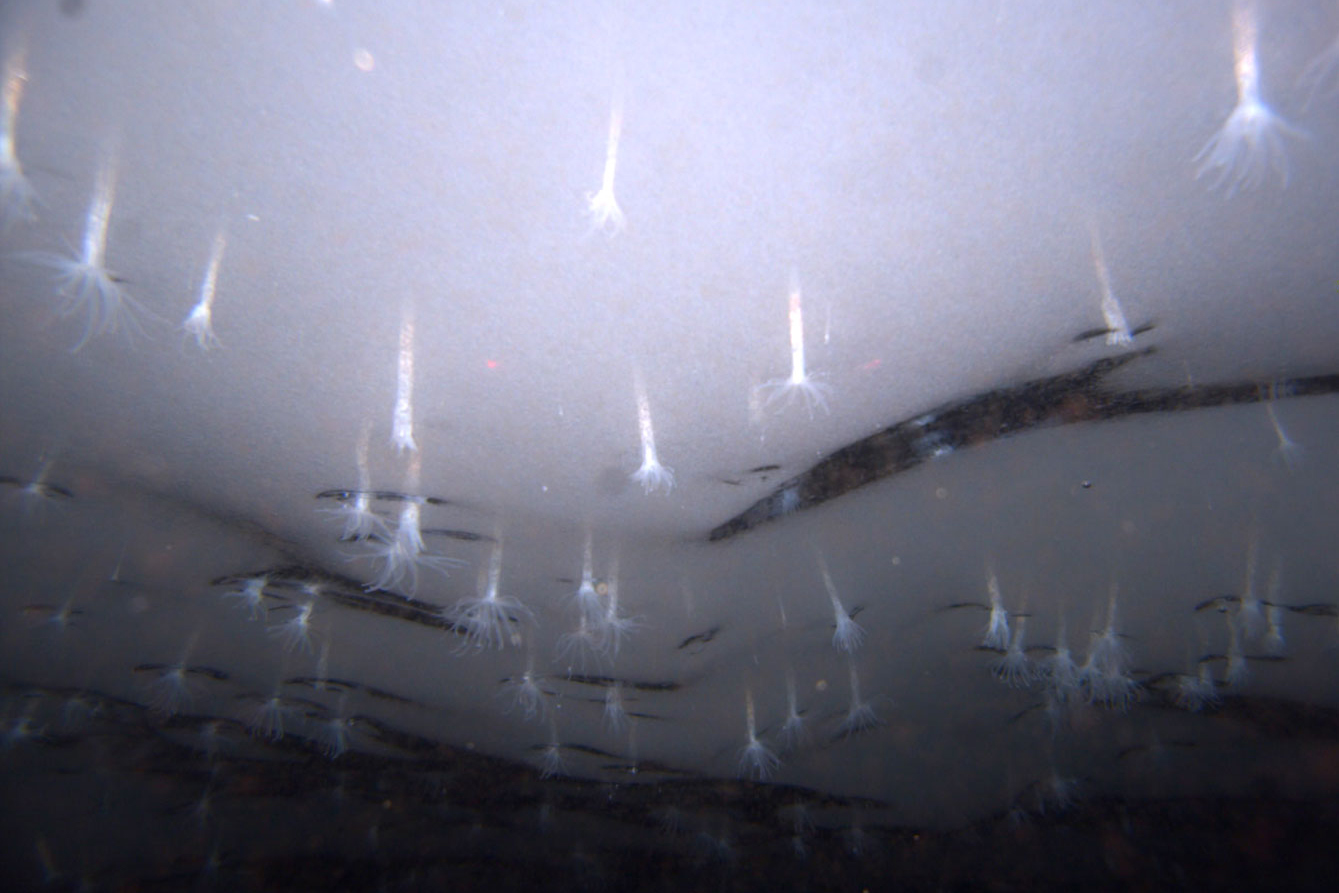

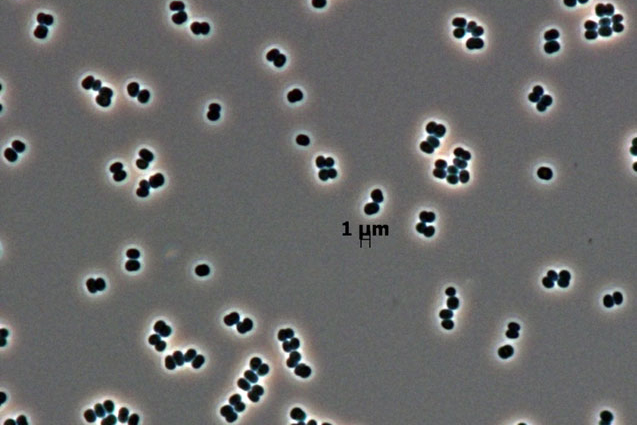

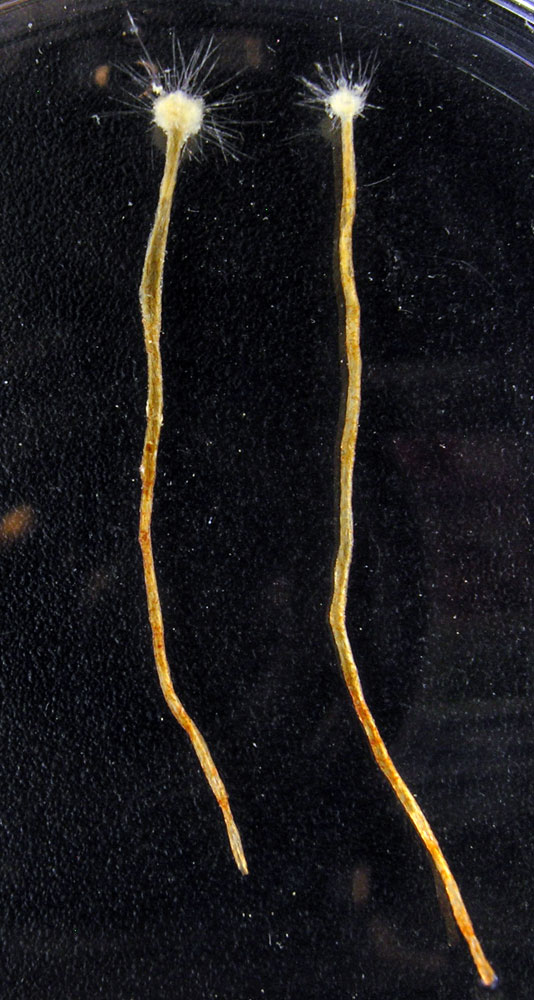

The Guinea worm is a parasite that enters the human body when the unwitting host-to-be drinks water contaminated with tiny water fleas in which Guinea worm larvae lurk. Once ingested, the fleas die and the Guinea worm larvae enter the host’s abdominal cavity and, unbeknownst to the host, begin maturing into a worm or worms that grow up to three feet in length. After about a year a painful blister forms on the host’s skin accompanied by itching and a burning sensation. Within about 10 to 15 days, one or more worms erupt from the person’s skin in a painful and drawn-out process. The emergence can occur from different parts of the body, including the roof of the mouth, the genitals, or the eye sockets, but around 90 percent of the worms emerge from the lower legs, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). (There are plenty of videos of Guinea worm extractions on YouTube, but be warned they’re quite unsettling.)

Top 10 New Species for 2014

While the disease rarely kills, it can leave the host debilitated and weakened for a short or long period of time.

“The lesions caused by the worms often develop secondary bacterial infections that migrate all along the tract where the worm was,” says Ernesto Ruiz-Tiben, the director of the Carter Center’s Guinea worm eradication program. “The pain and agony can last for weeks.”

To alleviate the pain, the infected person often dips the part of the body from which the worm has emerged into water, where the female worm that is emerging can lay more larvae, and begin the process anew.

A Disease on the Decline

Thanks in large part to the work of the Carter Center, the incidence of Guinea worm disease (also known as dracunculiasis, which is Latin for “affliction with little dragons”) has plummeted in recent years, falling from an estimated 3.5 million cases worldwide in the mid-1980s to just 148 in 2013 and 126 in 2014, according to the WHO.

How has such success been achieved? It’s taken the concerted effort of all involved—the scientists who have figured out how to contain it, community organizers who have helped spread the word on preventative solutions, and the people in areas where Guinea worm disease has been a big problem who are implementing the necessary changes to keep the parasite at bay.

“Guinea worm eradication is like an orchestra: Every player has to play their own instrument but play from the same page of music,” says Ruiz-Tiben.

WORLD SCIENCE FESTIVAL: The Rise of Preventable Illnesses

There’s No Cure for the Long-Lived Dracunculiasis, but Preventive Measures Are Finding Success

While it could disappear in the near future, dracunculiasis is a disease that has been around for centuries. It is believed to be the “fiery serpents” referenced in the Old Testament, and the calcified remains of a male Guinea worm were found in an Egyptian mummy.

The treatment has been around a long time too. A description found on an Egyptian papyrus from 1,500 BC outlines the treatment that’s followed today: Wind the worm around a stick as it emerges.

But unlike rinderpest and smallpox, Guinea worm disease cannot be vaccinated against. Preventing its infection is a matter of making sure people don’t drink the contaminated water. To that end, education and water filtration are key. Both cloth filters, used to filter large amounts of water in containers, and smaller pipe filters, used like a straw when drinking, can screen out the water fleas that carry the Guinea worm larvae. There are also ways of chemically treating water sources to reduce populations of water fleas, but the microorganisms eventually return.

“There’s no magic bullet against this disease,” Ruiz-Taben says. But “the more barriers we can put out there to interrupt the life cycle of this disease, the greater likelihood there is that we can interrupt transmission.”

Once spread across Africa, the worm is now holding on only in South Sudan, Mali, Chad, and Ethiopia. Stamping out those last few strongholds, says Ruiz-Taben, is just a matter of continuing the cooperative work that’s been going on since the 1990s. As the journalist Julius Cavendish wrote in the Bulletin of the World Health Organization this past December:

“Not only is guinea-worm disease relatively easy to control, in theory, but the benefits of eradication far outweigh the costs. … According to a 1997 World Bank study, the economic rate of return on the investment in Guinea-worm disease eradication will be about 29% per year once the disease is eradicated… removing guinea-worm disease translates into hundreds of thousands of communities better able to work their fields, send their children to school and escape the cycle of poverty and disease.”

WORLD SCIENCE FESTIVAL: How We Bounce Back: The New Science of Human Resilience

If Wiped Out, Could It Recrudesce?

If the number of cases drops to zero, there should be little chance of dracunculiasis coming back. There could be hurdles to its total annhilation, however. While Guinea worms (unlike Ebola) don’t seem to have a widespread tendency to hide out in animals when they’re not infecting humans, there have been a few reports of dogs with the worms reported in Chad; if this turns out to be a more common phenomenon, eradication efforts may have to turn to preventing those canine cases too. And if those countries that host the last areas of Guinea worm infestation were to suffer from war, famine, or other kinds of instability, that could slow the process of eradication. In Mali, for example, just seven cases were reported in 2012—but those numbers increased slightly in 2013 and 2014, when conflict with Islamist rebels hampered eradication efforts.

Still, the ultimate end looks to be within reach. Does Ruiz-Taben think he’ll see Guinea worm disease completely eliminated in his lifetime?

“I am very hopeful—more than hopeful,” he says.

WORLD SCIENCE FESTIVAL: What Will Happen to Your Body in 2015?

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com