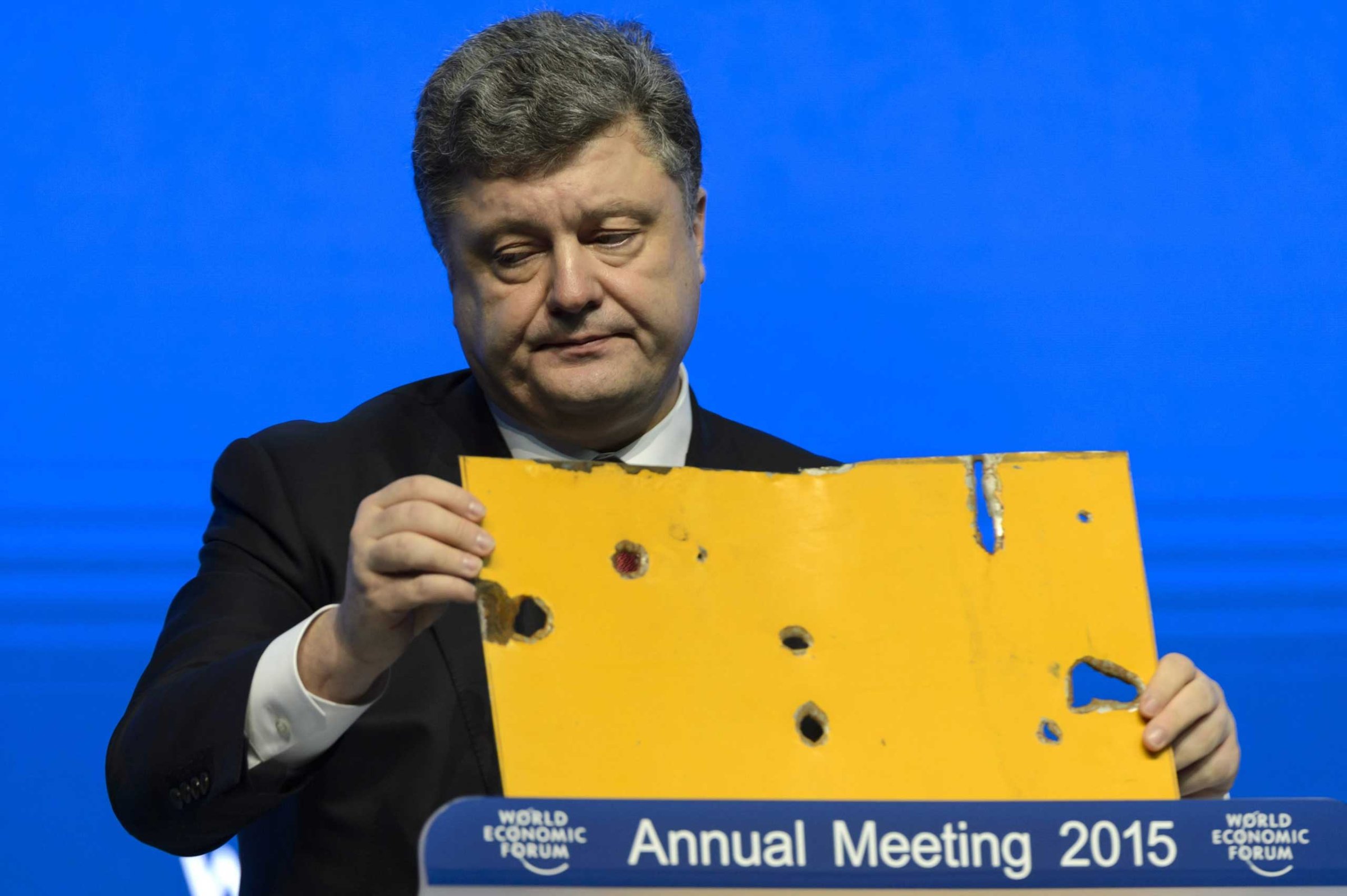

In the middle of his speech on Wednesday at the World Economic Forum, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko left the podium, walked to the edge of the stage and took a large hunk of metal from a man in the audience. It was a shrapnel-scarred panel from a public bus, Poroshenko explained, that was hit by a rocket on Jan. 13 near the Ukrainian town of Volnovakha, killing 13 of its passengers and wounding more than a dozen others.

“For me this is a symbol, a symbol of the terrorist attack against my country, the same way it is a symbol like Charlie Hebdo,” he said, referring to the French satirical weekly whose staff were massacred inside their newsroom on Jan. 9 by Islamist terrorists. Then Poroshenko pointed to a pin on his lapel that was inscribed with the words, ‘Je suis Volnovakha.’

The link he drew between these two tragedies was not an obvious one. The journalists of Charlie Hebdo were killed in a deliberate act of religious extremism, motivated by the newspaper’s publication of cartoons lampooning the Prophet of Islam. The passengers on the bus at Volnovakha were accidental casualties in a war that has already claimed almost 5,000 lives, most of them civilians. But Poroshenko needed to make that connection, not just to strike a chord with his audience of economists, investors and officials from around the world, but to push back against what Poroshenko later called “Ukrainian fatigue.”

By that he meant the growing wariness in the West with the Ukrainian crisis, and for Poroshenko’s government, it is nearly as dangerous as Russia’s military incursions. Nine months have passed since the war in Ukraine’s eastern provinces of Donetsk and Luhansk began, and there is still no clear prospect for a resolution. Despite the terms of a peace deal signed on Sept. 5, Russia has refused to close its border with Ukraine to the flow of weapons and reinforcements for the rebel militias. Indeed, just this week, Ukraine again raised the alarm over hundreds of Russian troops coming across the border to aid the rebels in a fresh assault.

But those developments have made far fewer headlines than they would have even a few weeks ago, before the world’s attention turned to the more shocking and immediate news from Paris and the threat from terrorism emanating from the Middle East. Already, it seems, Ukrainian fatigue is setting in and forcing Poroshenko to curb some of his hopes for Western support.

During his speech at the Davos forum, the President said that Ukraine is no longer asking for weapons supplies and other “lethal aid” from the West to help fight the conflict, even though that was one of Poroshenko’s key requests when he visited Washington in September to meet with President Barack Obama and other top U.S. officials.

His expectations for financial aid, however, seemed undimished in Davos. “We need a financial pillow [that] can support us during the reforms,” he said in his speech. On top of the $17 billion bailout that Ukraine secured in April from the International Monetary Fund, Poroshenko’s government needs about $15 billion more to plug a gap in its finances that could lead to bankruptcy if it continues to grow. A mission from the IMF has been in Kiev since Jan. 8, to review the possibility of providing that support, and in Davos on Wednesday, IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde said she would back a bigger funding program for Ukraine, though she did not provide any specific figures.

For Poroshenko, securing that aid will not just mean carrying out the steep budget cuts and other financial reforms that have come as a condition of IMF loans. He will also need to keep sympathy for Ukraine from fading in the minds of his Western counterparts and the taxpayers they represent. His rhetoric in Davos seemed geared to that purpose.

“We are fighting for European security. We are fighting for European values,” he said in his speech. “Somebody said that this is very expensive to fight for peace… They measured expenses by price and said that it is very expensive. We and all the civilized world are fighting for values,” he concluded. But now, as the war in Ukraine drags on, it will be up to Western lenders to judge how much support those values will be worth.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington Meet the 2025 Women of the Year Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer? Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love 11 New Books to Read in February How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in February

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com