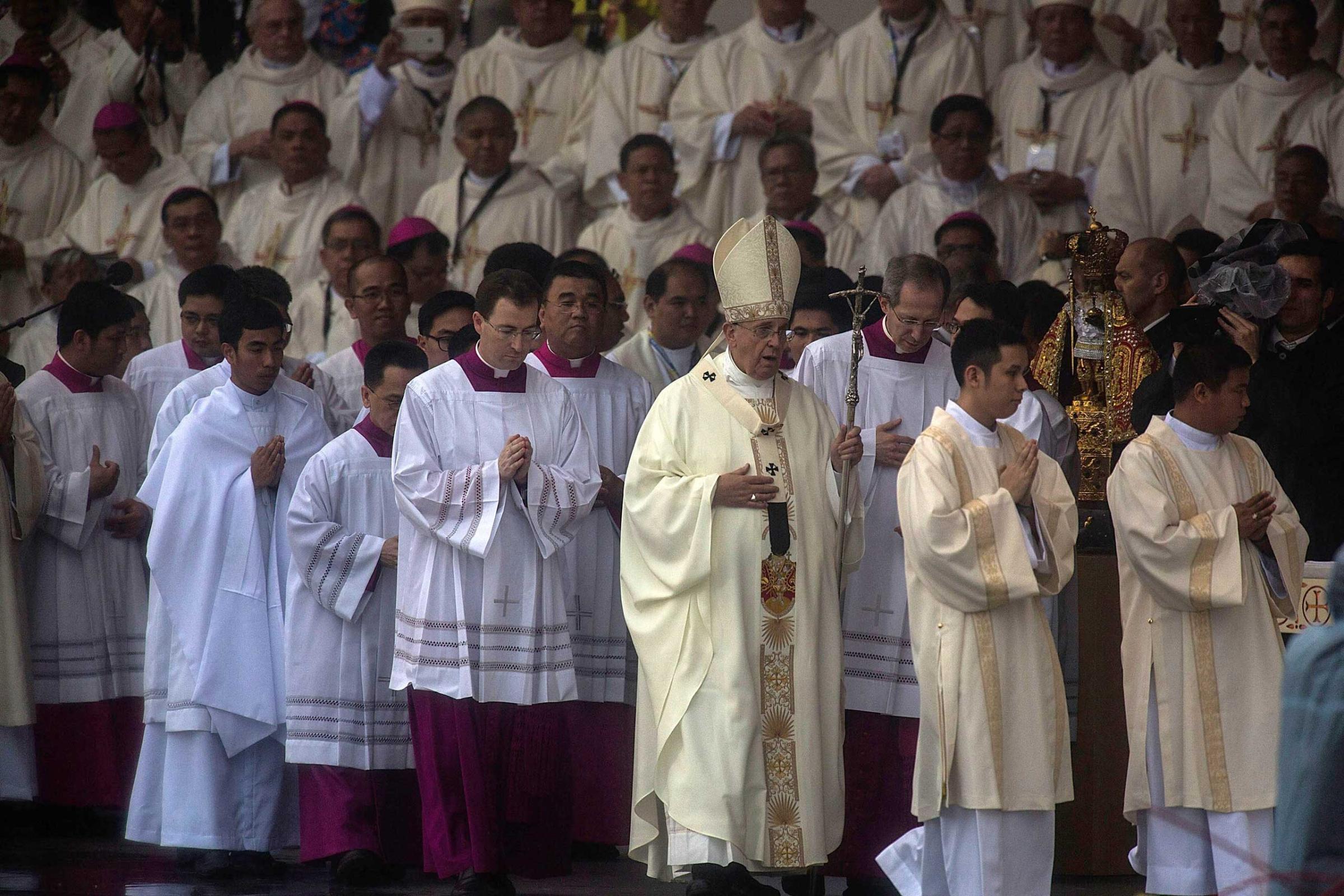

Pope Francis took the helm of the Catholic Church last year, vowing to refashion the institution “for the poor.” Yet during his recent five-day visit to the Philippines, where he presided over Mass for more than six million rapturous worshippers, it appeared many of the nation’s most impoverished were cruelly banished from view.

As the Pontiff touched down in Asia’s most Catholic nation, reports emerged that street children had been rounded up and caged in order to sanitize Manila’s streets. Local authorities vehemently denied this was a case, pointing out that the accompanying photographs of an emaciated toddler and young girl handcuffed to a metal pole had in fact been taken months earlier.

However, rumors continued to swirl as more anecdotal evidence arrived. So was the Philippine capital purged of unsightly urchins? In a word, yes, although only a small fraction of this was anything new.

According to local activists, street children are constantly being rounded up across this sprawling metropolis of 12 million. This is generally for vagrancy and petty crime — they are often scapegoats for the deeds committed by organized gangs — and, although numbers are hard to pin down, the Pope’s visit seemed to herald a slight uptick.

“There’s definitely been a ramp up,” Catherine Scerri, deputy director of the Bahay Tuluyan NGO that helps street children, tells TIME. “They were definitely told not to be visible, and many of them felt that if they didn’t move they would be taken forcibly.”

Those detained end up a various municipal detention centers sprinkled all over Metro Manila, says Father Shay Cullen, the Nobel Peace Prize-nominated founder of the Preda Foundation NGO. These local adult jails each adjoin euphemistically named “children’s homes,” which, like the adult facility, has bars on the windows.

Children are summarily kept for anything up to three months without charge, with little ones sharing cells with young adults. Many fall prey to serious sexual and physical abuse: Kids just eight-years-old are often tormented into performing sex acts on the older detainees, says Cullen. (Amnesty International documented such abuses in a December report.)

“They are locked up in a dungeon,” says Cullen, explaining that some 20,000 children see the inside of a jail cell annually across the Philippines. “We keep asking why they put these little kids in with the older guys.”

Nevertheless, Philippines Welfare Secretary Corazon Juliano-Soliman explicitly denies that homeless children were rounded up for the Papal visit, highlighting that they were, in fact, central to the 78-year-old Pontiff’s reception. Some 400 homeless kids — albeit in bright, new threads — sang at a special event (and posed awkward theological questions.)

Any children detained, explains Juliano-Soliman, were “abandoned, physically or mentally challenged or found to be vagrant or in trouble with the law, and we are taking care of them.” Father Cullen’s allegations, Juliano-Soliman suggests, are a sympathy ploy to win donations “One can’t help but think it’s a good fundraising action,” she says wryly.

However, Juliano-Soliman did confirm that 100 homeless families — comprising 490 parents and children — were taken off the street of Roxas Boulevard, the palm-fringed thoroughfare arcing Manila Bay along which Pope Francis traveled several times, and taken about an hour and a half’s drive away to the plush Chateau Royal Batangas resort. Room rates there range from $90 to $500 per night.

This sojourn lasted from Jan. 14, the day before Pope Francis’s visit, until Jan. 19, the day he left. It was organized by the Department of Social Welfare’s Modified Conditional Cash Transfer program, which provides grants to aid “families with special needs.”

Juliano-Soliman says this was done so that families would “not be vulnerable to the influx of people coming to witness the Pope.” Pressed to clarify, she expressed fears that the destitute “could be seen as not having a positive influence in the crowd” and could be “used by people who do not have good intentions.”

For Scerri, though, this reasoning doesn’t cut it: “It’s very difficult to believe that children and families who have lived on the streets for most of their lives need to be protected from what was a very joyous, very happy, very peaceful celebration.”

In fact, families involved were only told two days prior that they were to make the trip to Chateau Royal Batangas. “Many felt that if they didn’t participate that they would be rounded up,” says Scerri, adding that those who returned to their usual digs by Malate Catholic Church found large signs had been painted in the interim that prohibited sleeping rough.

Ultimately, whether jailed or stashed in a resort, “there’s nothing new,” says Father Cullen. “Every time dignitaries come it’s a common phenomenon for more children to be locked up.”

So where did Manila’s street children go? The truth is that most people didn’t really care, just as long as they did.

Pope Francis Holds Giant Mass in the Philippines

Read next: Pope Calls Out Philippines on Corruption and ‘Scandalous’ Inequality

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Charlie Campbell at charlie.campbell@time.com