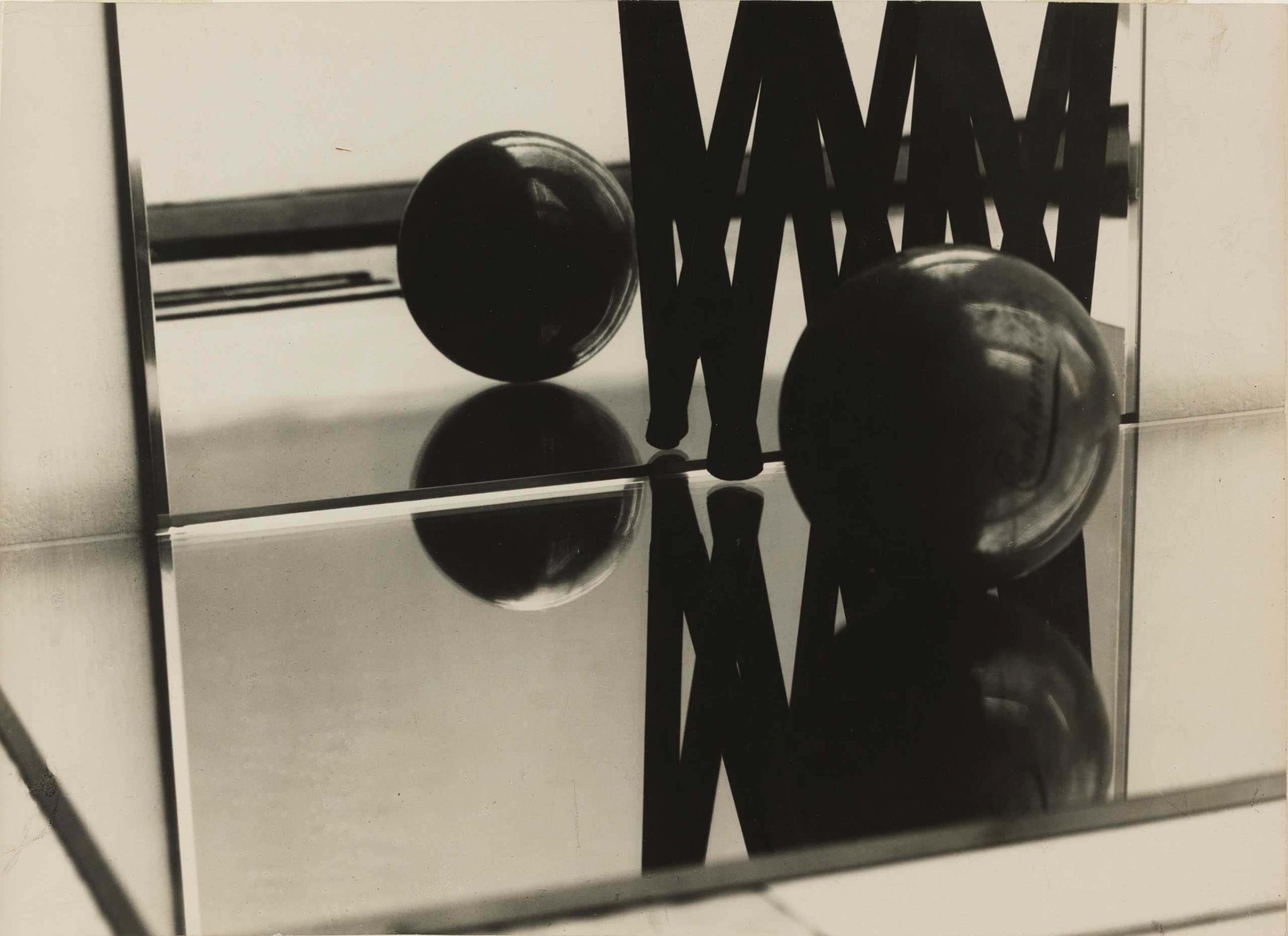

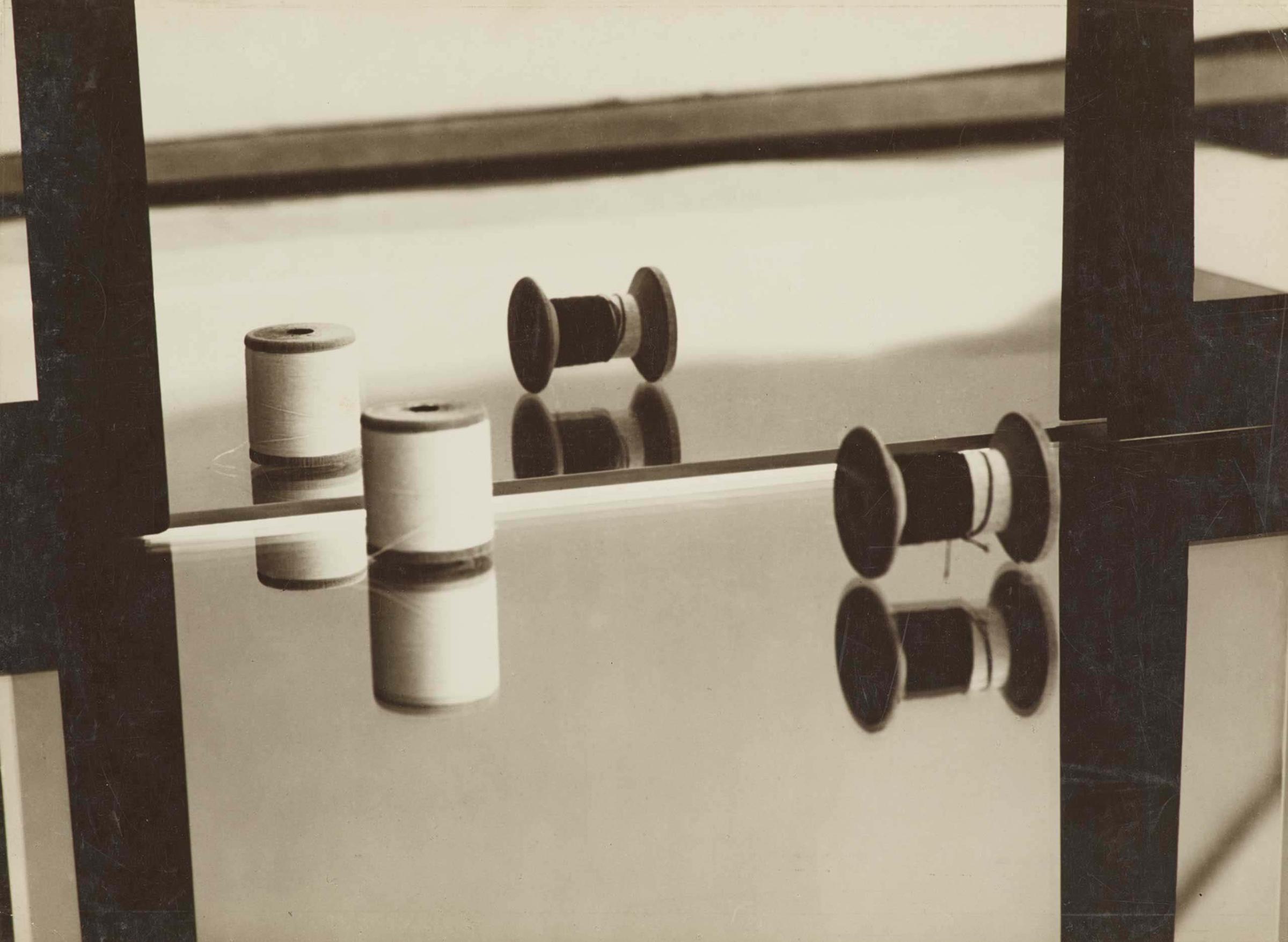

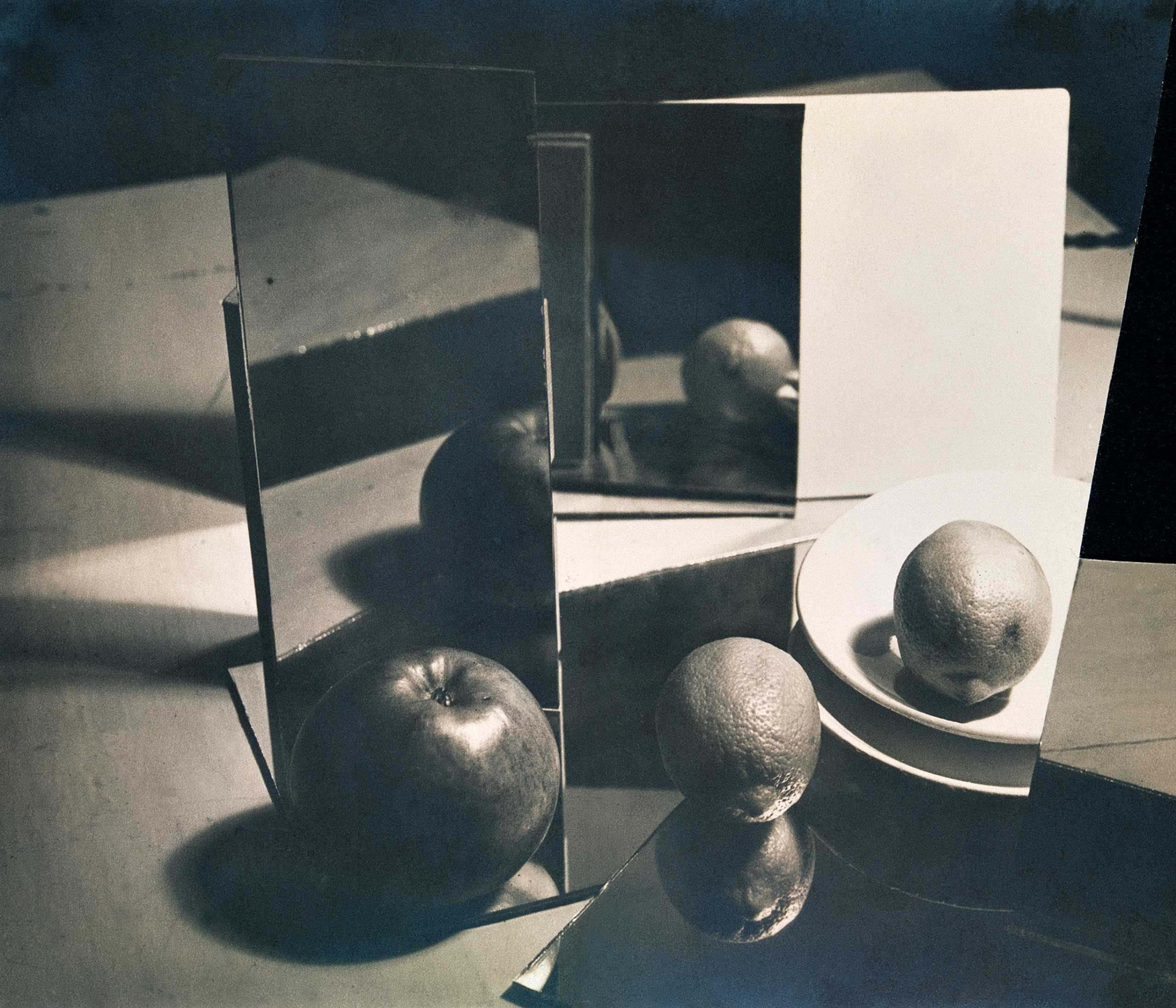

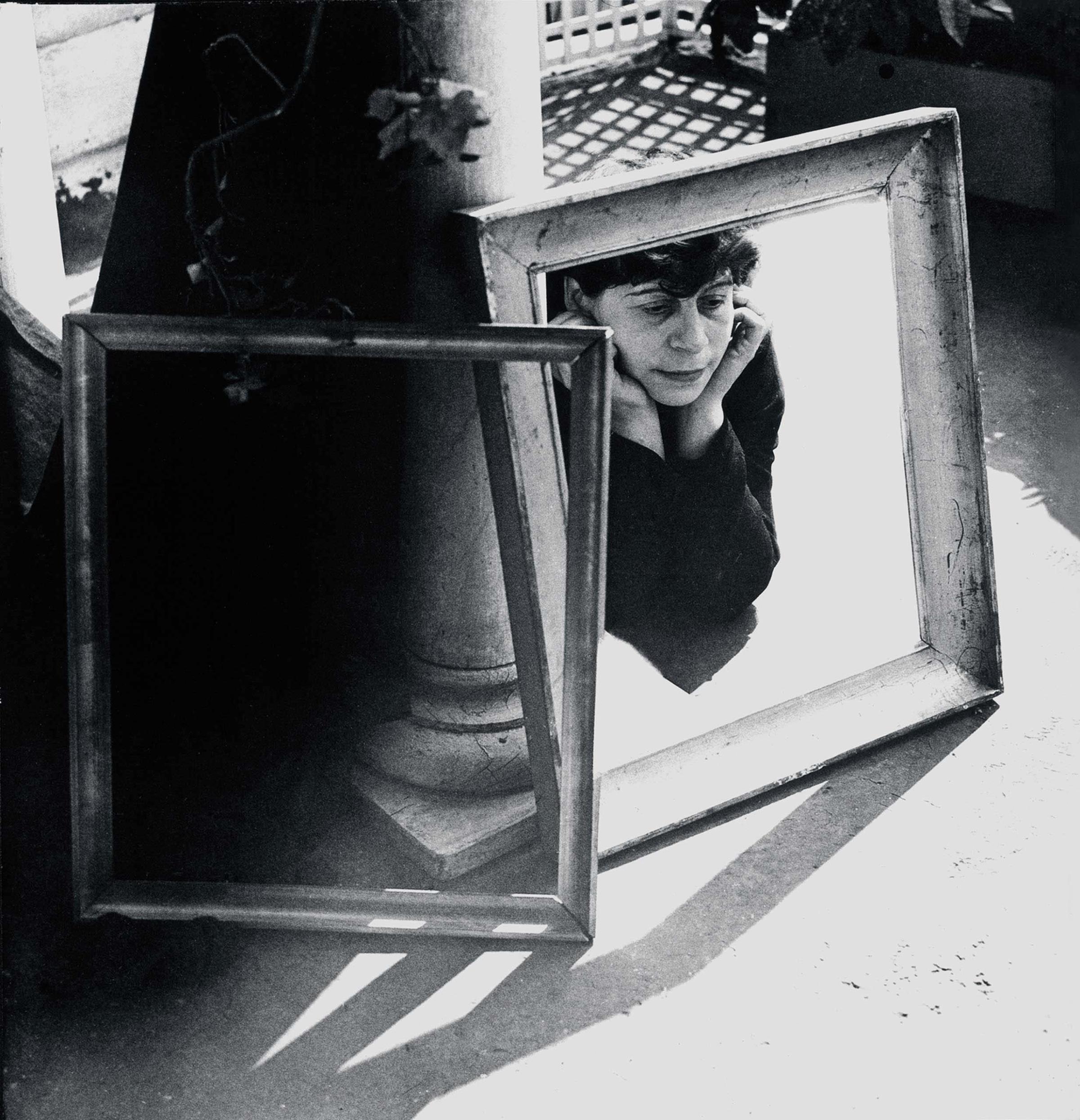

“What I want above all,” Florence Henri said near the end of her long life, “is to compose the photograph as I do with painting. Volumes, lines, shadows and light have to obey my will and say what I want them to say. This happens under the strict control of composition, since I do not pretend to explain the world nor to explain my thoughts.”

Henri began her artistic career as an abstract painter but, upon studying at the Bauhaus in Germany, turned to photography as what she perceived as the medium of the future. In 1929, just two years after leaving the Bauhaus, Henri’s Paris portrait studio became as well-known as that of Man Ray. She taught classes, and her students included future luminaries such as Gisèle Freund and Lisette Model

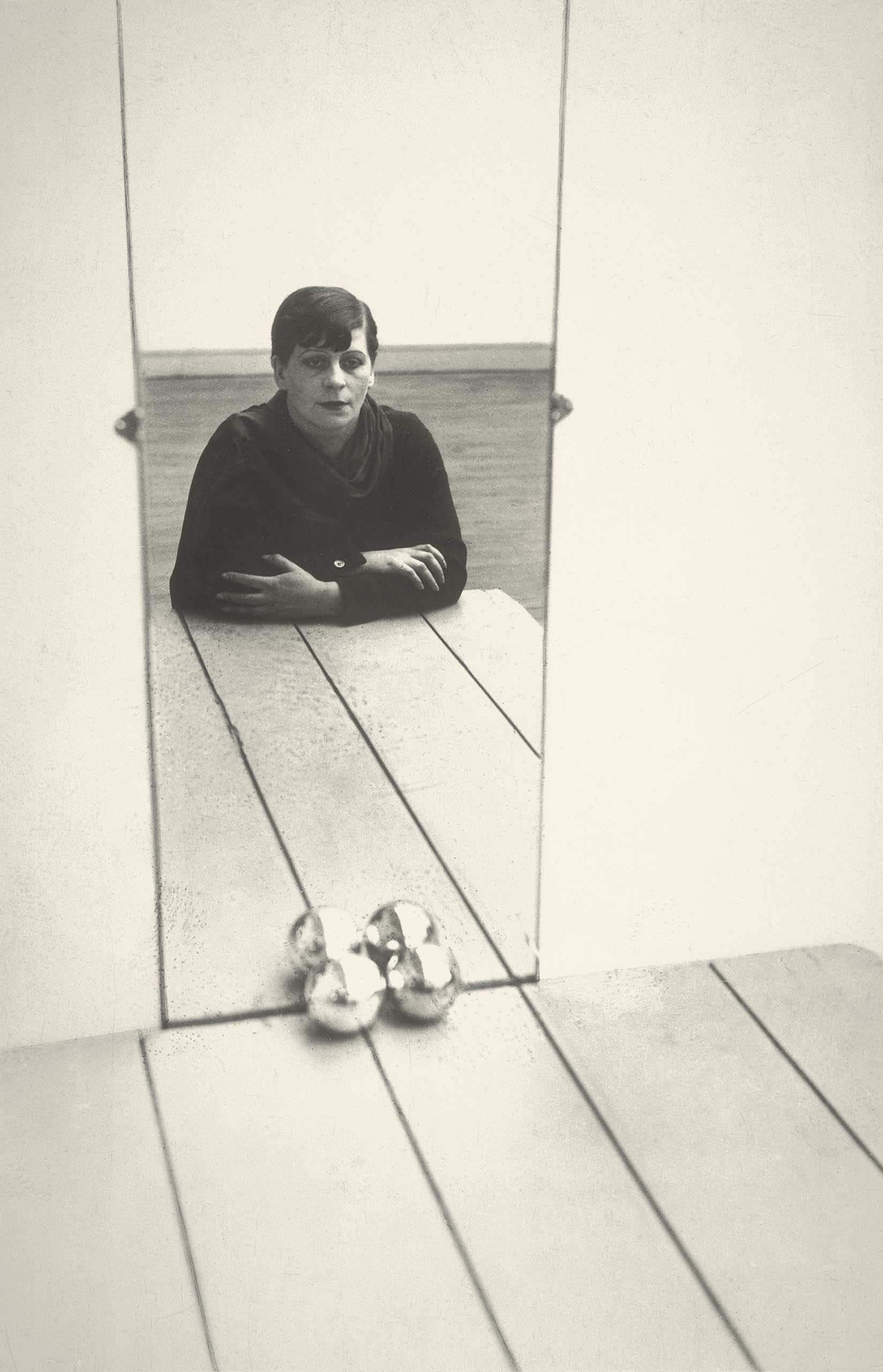

Early on, influenced by Constructivism and Cubism, Henri started experimenting with mirrors as a way to add more perspectives to her imagery. First she used them simply as reflections for her portraits and self-portraits, then gave them a much more central role. Her self-portrait with spheres, where she is reflected both by a mirror and by metal spheres, quickly became a famous modernist landmark. Henri’s photographs became part of seminal international exhibitions, such as Fotografie der Gegenwart (Contemporary Photography, 1929), Film Und Foto (Film and Photo, 1929) and Das Lichtbild (The Photograph, 1931). At that time, due to Henri’s fame in Europe, she became influential in the field: photographer Ilse Bing, for instance, explained that she wanted to settle in Paris because Florence Henri worked there and she felt close to her ideas.

Now, Henri’s contributions to the field are, for the most part, unknown to the larger public.

The new exhibition of Henri’s work, Mirror of the Avant Gardes at the Musée du Jeu de Paume in Paris, attempts to remedy this omission by bringing together 130 vintage prints from the Florence Henri Archive in Genova, Italy, as well as little-known publications and documents related to the artist’s life and work. The accompanying catalogue includes numerous documents from the period as well as reproductions of works by other artists of the time, drawing parallels and comparisons to Henri’s work and placing it in context.

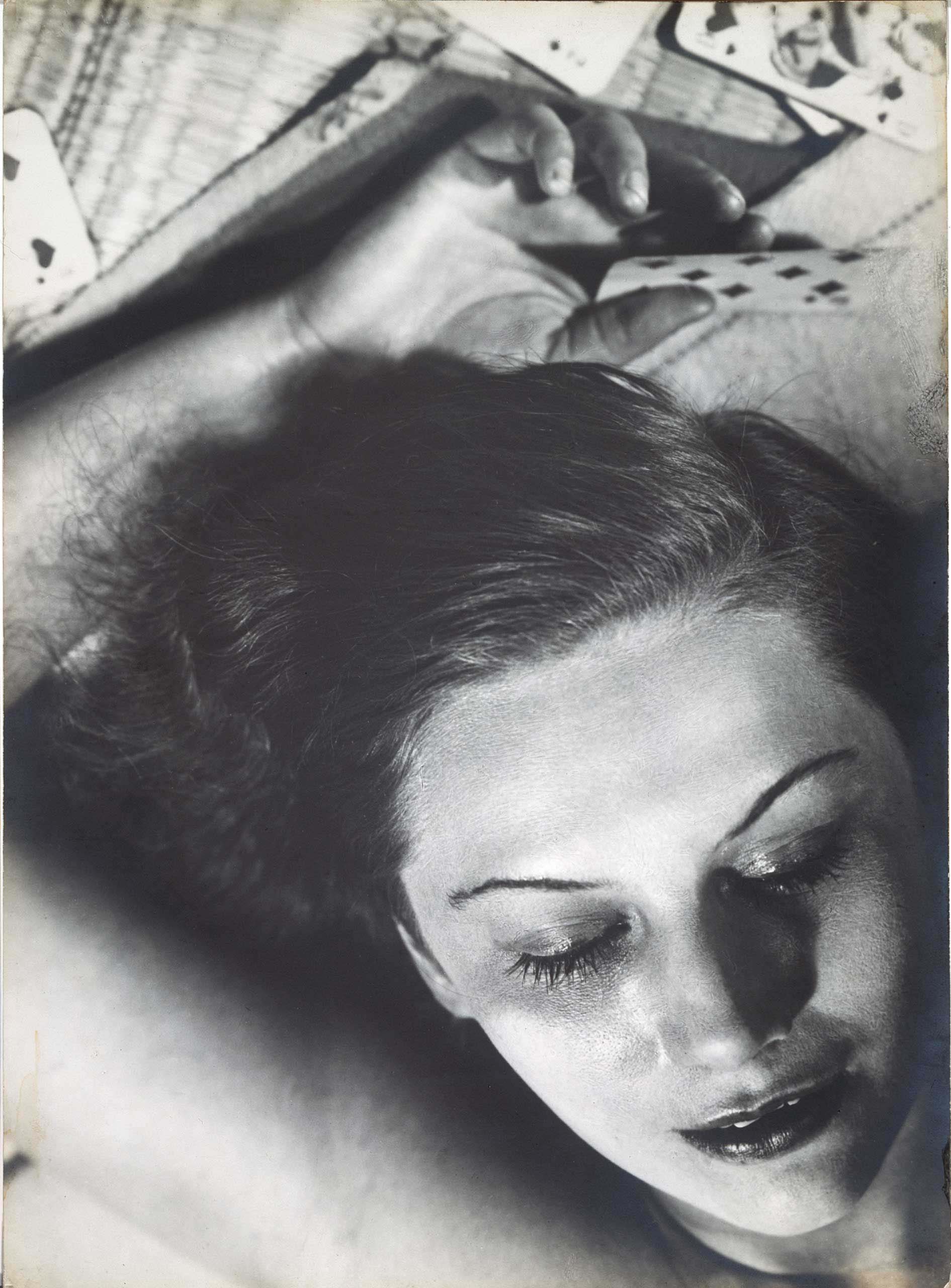

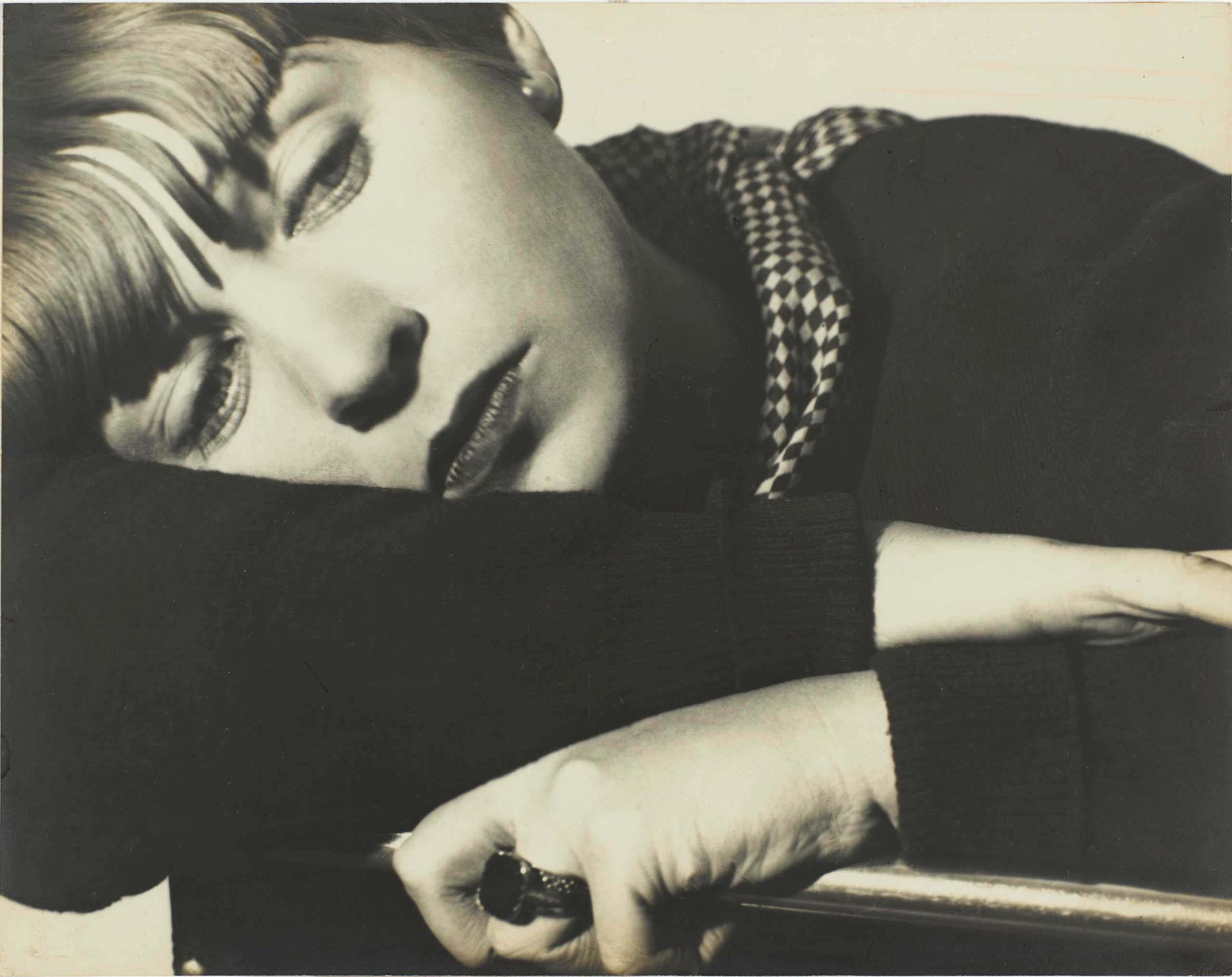

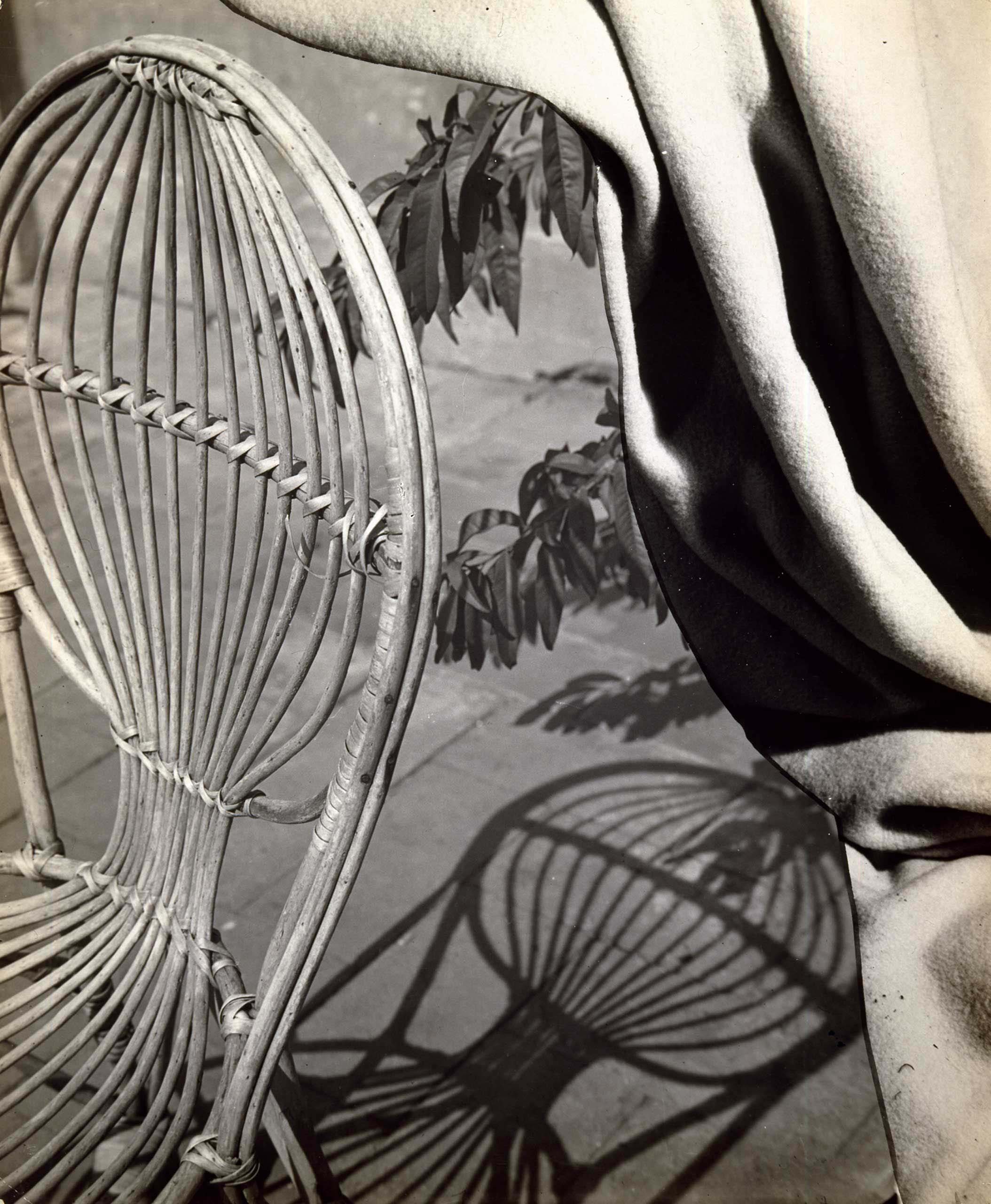

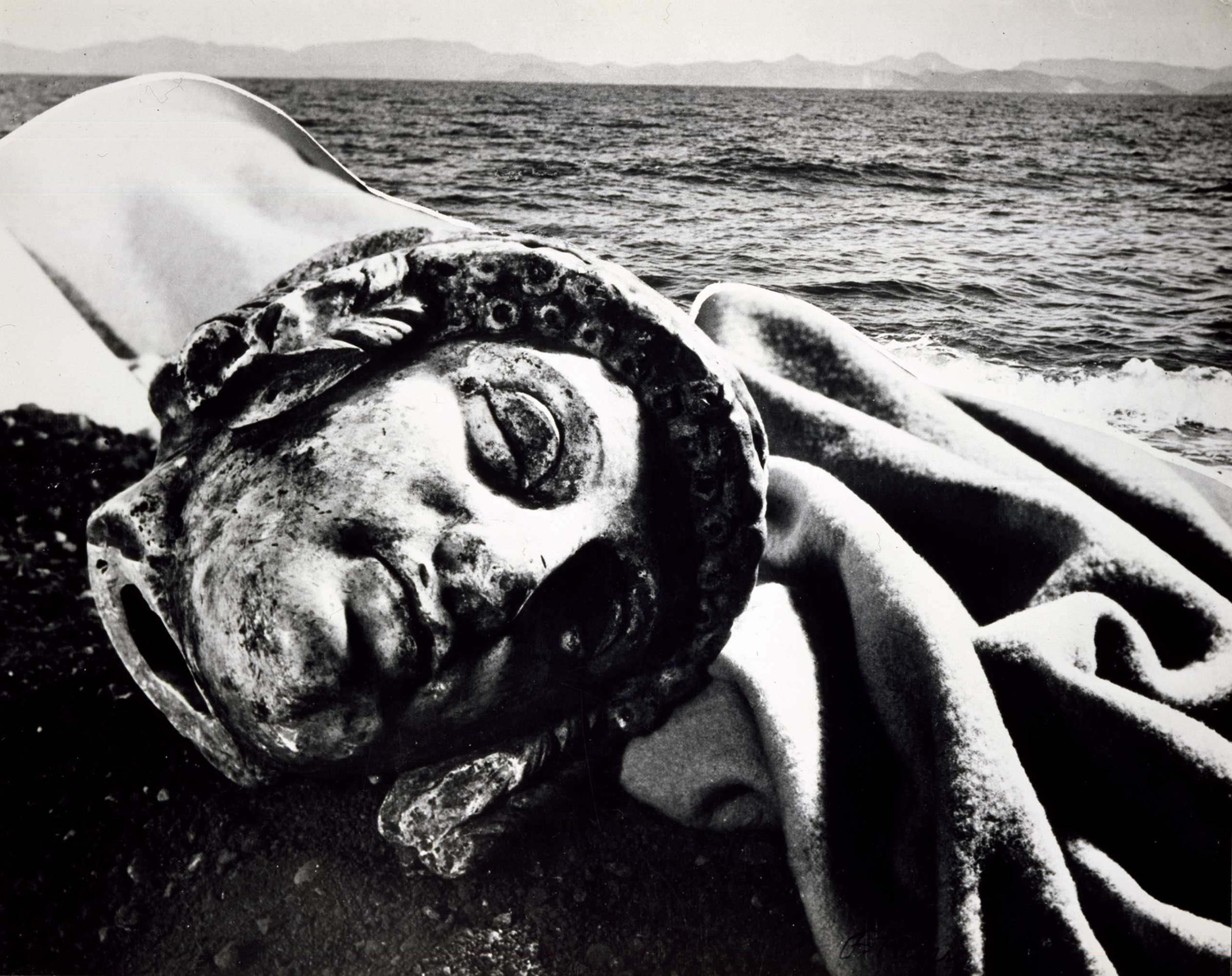

Henri’s wide-ranging work explores the mechanics of perception. They include numerous portraits of her artist friends (among them Jean Arp, Petra Van Doesburg, Sonia Delaunay, Wassili Kandinsky Fernand Léger, and Margarete Schall). There are also still lifes, mostly of industrial objects; abstract compositions; advertising photos (for products from Lanvin, Columbia, Ambre Solaire, and others); numerous self-portraits; sensual female nudes that often include natural elements such as shells or hyacinths (many were published as a book, Femmes Nues in 1935); and street photographs taken in Rome, Paris and Brittany.

There is also an exceptional Vitrines series, layered reflections from shop windows, as well as photomontages made from her own cut-up photographs of Roman architectural details. Henri often uses deep shadows that bisect and fragment the image. She also explores multiple exposures or combines several negatives to obtain dynamic juxtapositions. In a recent conversation, The show’s curator Cristina Zelich remarked that an “interesting trait is her work method of exhausting all the composition possibilities offered by a small number of natural or industrial objects. Her use of collage is original; it differs from that of the Surrealists, because for her it is not about creating a link with the unconscious, but about organizing in different patterns the reality that she photographs with her camera.”

The thread that weaves all these diverse subjects together is Henri’s designing eye, conditioned by her sensitivity to geometric abstract painting and the innovations of the New Vision photography as defined by her mentor Moholy-Nagy. Thanks to thoughtful exhibitions such as Mirror of the Avant Gardes, our knowledge of this complex period, which has been dubbed “The Second Birth of Photography,” becomes deeper and more nuanced, with a greater appreciation for the innovative work that can be viewed as having at times transcended today’s visual experiments.

Florence Henri‘s retrospective Mirror of the Avant Gardes at the Musée du Jeu de Paume in Paris, France runs until May 17, 2015.

Carole Naggar is a photo historian, poet and regular contributor to LightBox.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com