The spy is having a moment in television. Tonight, The Americans, the FX show about two KGB spies posing as stars-and-stripes-loving suburban Americans, returns for a third season. Premiering Feb. 5, NBC’s Allegiance will follow the CIA agent son of a former Soviet spy. From State of Affairs to Homeland, viewers can’t seem to get enough of the wigs and fake mustaches and regular brushes with death.

Tracing TV history back to the 1950s, every decade had its go-to secret agent men (and they were mostly men). In that decade it was Shadow of the Cloak’s Peter House and Biff Baker, U.S.A.’s titular character. In the ’60s and early ‘70s it was Maxwell Smart (Get Smart) and Jim Phelps (Mission: Impossible). Ever since the Cold War first captured Americans’ fears, it also captured their imaginations. And as potential spy rings are revealed in present times–just this week three Russian citizens were charged with espionage in New York City–the possibility of spies among us is not just old-fashioned paranoia.

Some of these shows have taken pains to mimic actual spy tactics as closely as possible. The creator of The Americans and producers of State of Affairs are former CIA officers. Sixty years ago, I Led 3 Lives and Behind Closed Doors based episodes on real cases, Law and Order-style, and received federal approval before airing. Ex-spy advisors and government approval have meant that these shows can, on the one hand, come fairly close to accurate portrayals, while still, on the other hand, refraining from revealing anything too sensitive.

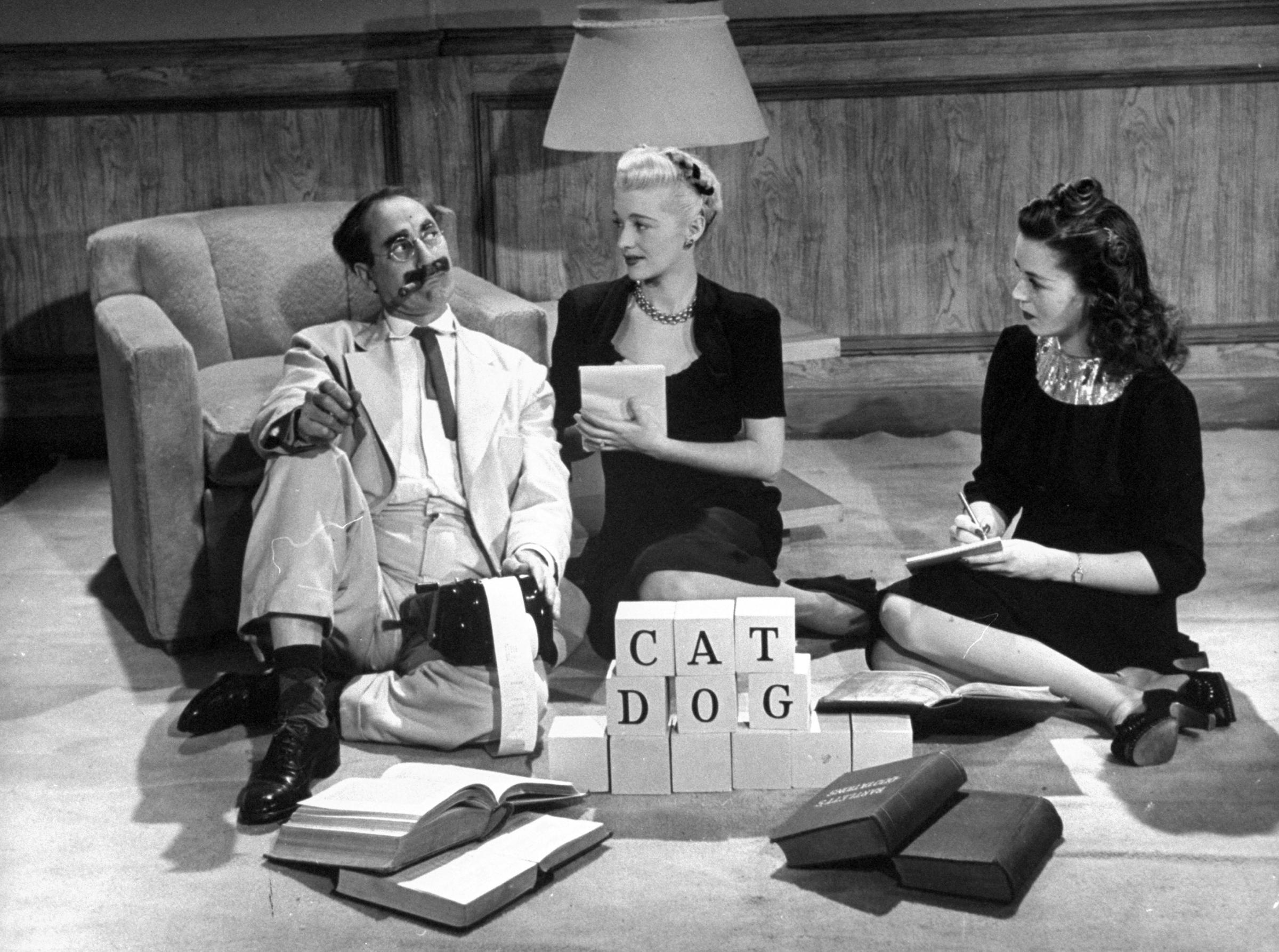

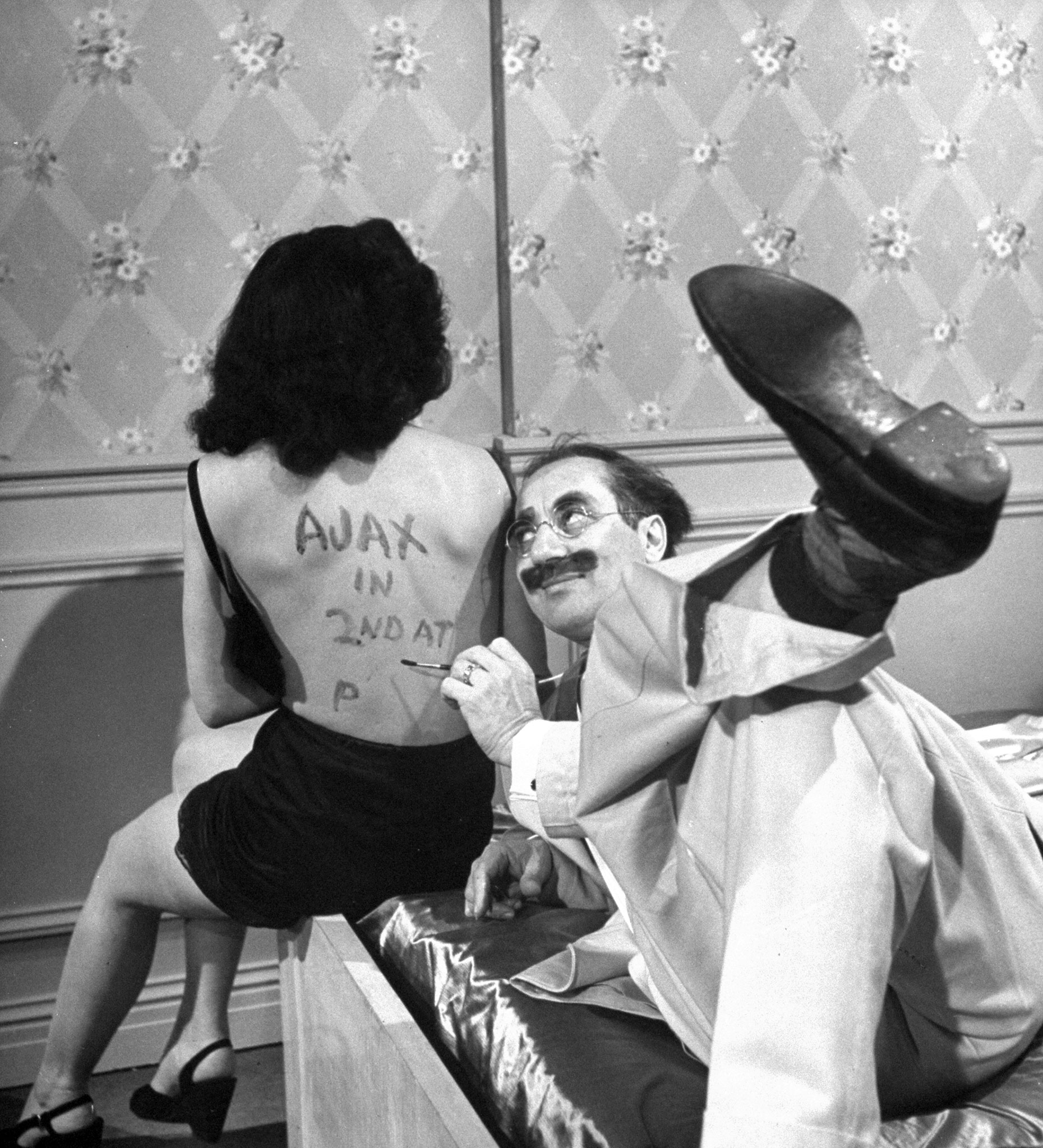

Plausibility was not, however, a concern for Groucho Marx, whose commitment to absurdity was as fervent as Americans creator Joe Weisberg’s is to verisimilitude. Appearing in LIFE in April 1946 to promote his forthcoming movie (with brothers Harpo and Chico), A Night in Casablanca, Marx offered the only take on espionage that could be expected of him: an utterly facetious one.

Pulling the kind of careless stunts that would have The Americans’ Philip and Elizabeth shipped back to the motherland for treason, Marx’s “How to Be a Spy” would have been more honestly titled, “How to Fail Your Country and Give Away All Your National Secrets.” Marx’s modus operandi is one of comfort and leisure: Chewing on a cigar, seducing women, peering through keyholes at half-dressed ladies, his spying, LIFE wrote, “is generally done in pleasant surroundings.”

The movie itself, the twelfth of the brothers’ 13 films, focused not on Soviets but on a Nazi war criminal–WWII had ended less than a year before, and it would be another year until President Truman would announce his strategy for the containment of Communism. A Night in Casablanca was meant to spoof the spy genre at large, and its parodic take would become increasingly rare for a period of time as the Red Scare became, to many, increasingly scary.

Photographer Bob Landry took the pictures in the spread, but Marx crafted the scenarios and the captions. As LIFE explained:

The Marxian machinations which resulted from his study are presented here. All incidents and commentary were devised personally by Mr. Marx in his capacity as Marx the Master Spy. More than that, all research is offered free to the Office of Strategic Services as Mr. Marx’s contribution to national security.

Safe to assume they respectfully declined.

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com