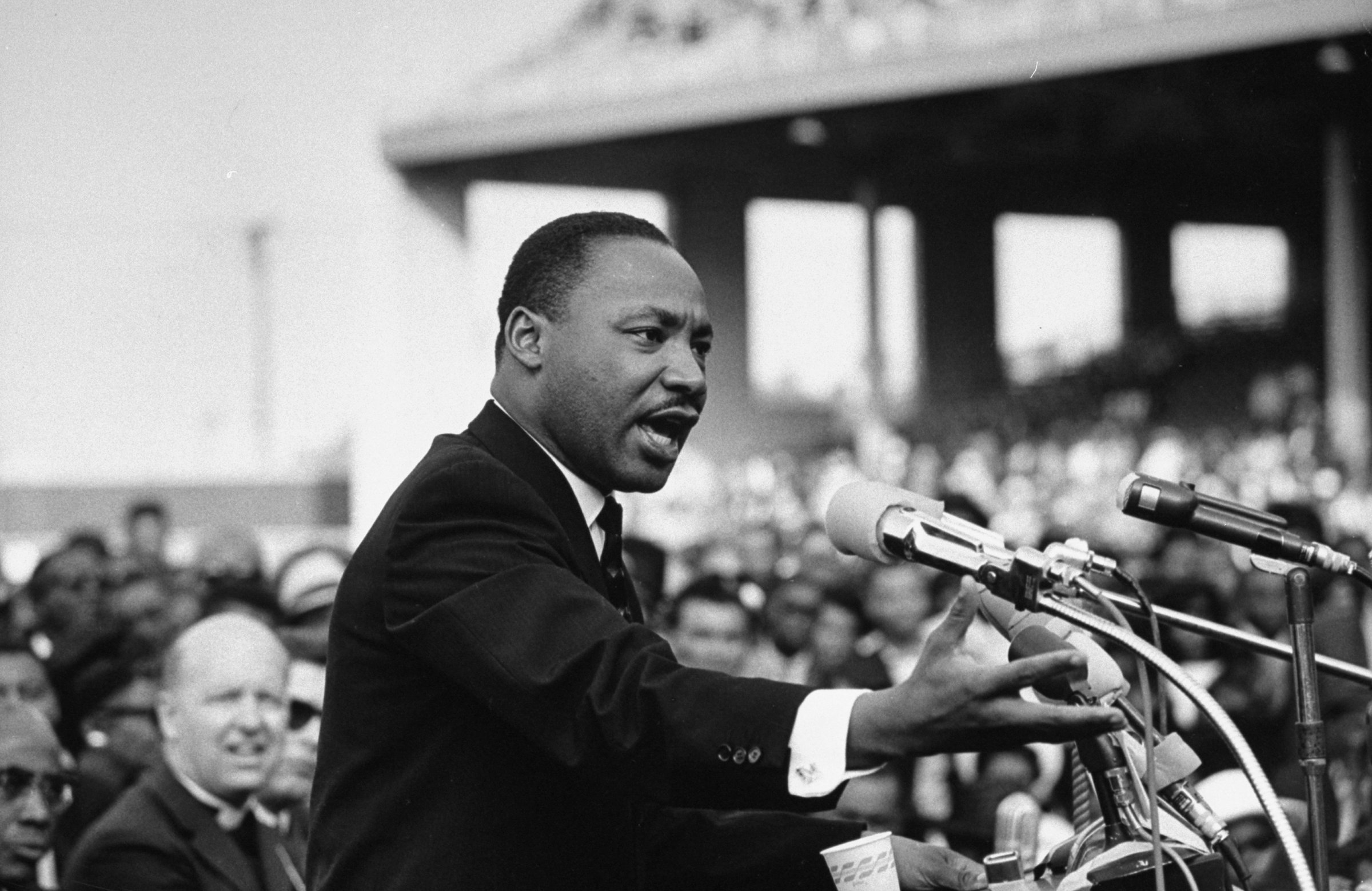

I have mixed emotions about Martin Luther King Jr. Day. For me, it’s a time of hopeful celebration — but also of cautionary vigilance. I celebrate an extraordinary man of courage and conviction and his remarkable achievements and hope that I can behave in a manner that honors his sacrifices. And while Dr. King still has his delusional detractors who have a dream of dismissing his impact on history, it’s not them I worry about.

His legacy may be in more danger from those who admire him.

Why? Because it’s tempting to use this day as a cultural canonization of the man through well-meaning speeches rather than as a call to practice his teachings through direct action.

For some, the fact that we have Martin Luther King Jr. Day is a confirmation that the war has been won, that racism has been eliminated. That we have overcome. But we have to look at the civil rights movement the way we look at antibiotics: just because some of the symptoms of racism are clearing up, you don’t stop taking the medicine or else the malady returns even stronger than before. Recent events make clear that the disease of racism is still infecting our culture and that Martin Luther King Jr. Day needs to be a rallying cry to continue fighting the disease rather than just a pat on the back for what’s been accomplished.

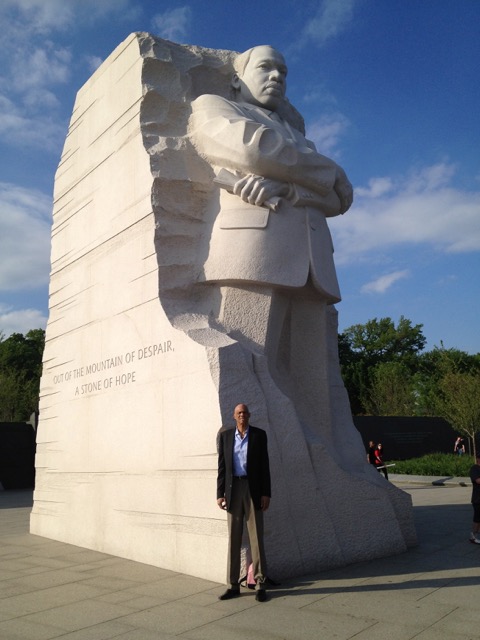

History has a tendency to commemorate the very thing it wishes to obfuscate. When you convince people that they’ve won, they lose some of their fire over injustice, their passion to challenge the status quo. In Alan Bennett’s brilliant play, The History Boys, one of the teachers explains to his students why a World War I monument to the dead soldiers isn’t really honoring them but rather keeping people from demanding answers as to how Britain unnecessarily contributed to the cause of the war and is therefore responsible for their deaths. By appealing to our emotional sense of loss, the government’s monument distracts people from holding the hidden villains responsible. The teacher says, “And all the mourning has veiled the truth. It’s not lest we forget, but lest we remember. That’s what this [war memorial] is about … Because there’s no better way of forgetting something than by commemorating it.”

One of the major debates this year has been whether or not racism exists anymore in America. Not surprisingly, polls indicate that most African Americans say, Yes, it does exist, while most white Americans say it doesn’t. Blacks point to disproportionate prosecution and persecution of blacks by authorities, and whites point to President Obama and dozens of laws protecting and promoting minorities.

They are both right. There are plenty of laws and government agencies dedicated to eradicating racism. The U.S. has made it a priority. Affirmative-action programs have created more opportunities for minorities, sometimes at the expense of whites seeking those same opportunities. That should be acknowledged and appreciated.

But suppressing racism is like pressing on a balloon: you flatten one end and it bulges somewhere else. Racism has gone covert. For example, the Republican effort to pass laws demanding IDs to combat voter fraud is itself fraudulent and racist. It is a form of poll tax, which was outlawed by the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The poll tax was designed to keep blacks from voting, as is the voter ID. It costs money and time away from work, which is too great a burden for the poor, many of whom are minorites. The justification given is to stop voter fraud. However, a recent study concluded that out of 1 billion votes cast, there have been only 31 incidents of voter fraud.

The reason whites don’t agree that racism is rampant is because most of them aren’t personally racist and they resent the blanket accusation. In fact, they see themselves as victims of reverse racism. They, too, are right. Dr. King would have acknowledged their pain and fought to alleviate it by reminding us not to confuse institutional racism with the good hearts of our neighbors. The civil rights movement would not have achieved as much as it has without the support and sacrifice of white America.

Dr. King would have been proud to see so many people across America — white and black — joining together to demand accountability in the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. He would have praised the millions who marched in France in support of freedom of speech. As he once said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

He would have also been disturbed by the violence and rioting that has occurred during these protests. We must remember that Dr. King’s cause was not just equality for all people but achieving that equality through nonviolence. The ends do not justify the means; the means and the ends are the same. Violence insults his legacy. To him, anything won through force is not won at all — it is loss. He wanted equality achieved through love because he wanted to win over his enemies, not defeat them. As he said, “Love is the only force capable of transforming an enemy into a friend.” His goal was to cleanse the community, not to cleave it.

Martin Luther King Jr. was only 39 years old at the time of his assassination nearly 47 years ago. When he died, those whom he had inspired were there to pick up the banner of the cause and continue marching. “I’ve looked over, and I’ve seen the promised land!” he told us. “I may not get there with you, but I want you to know tonight that we as a people will get to the promised land.”

Forty-seven years later, we must continue stepping lively, not in his name but for his cause.

Read next: The Return of the Protest Song

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com