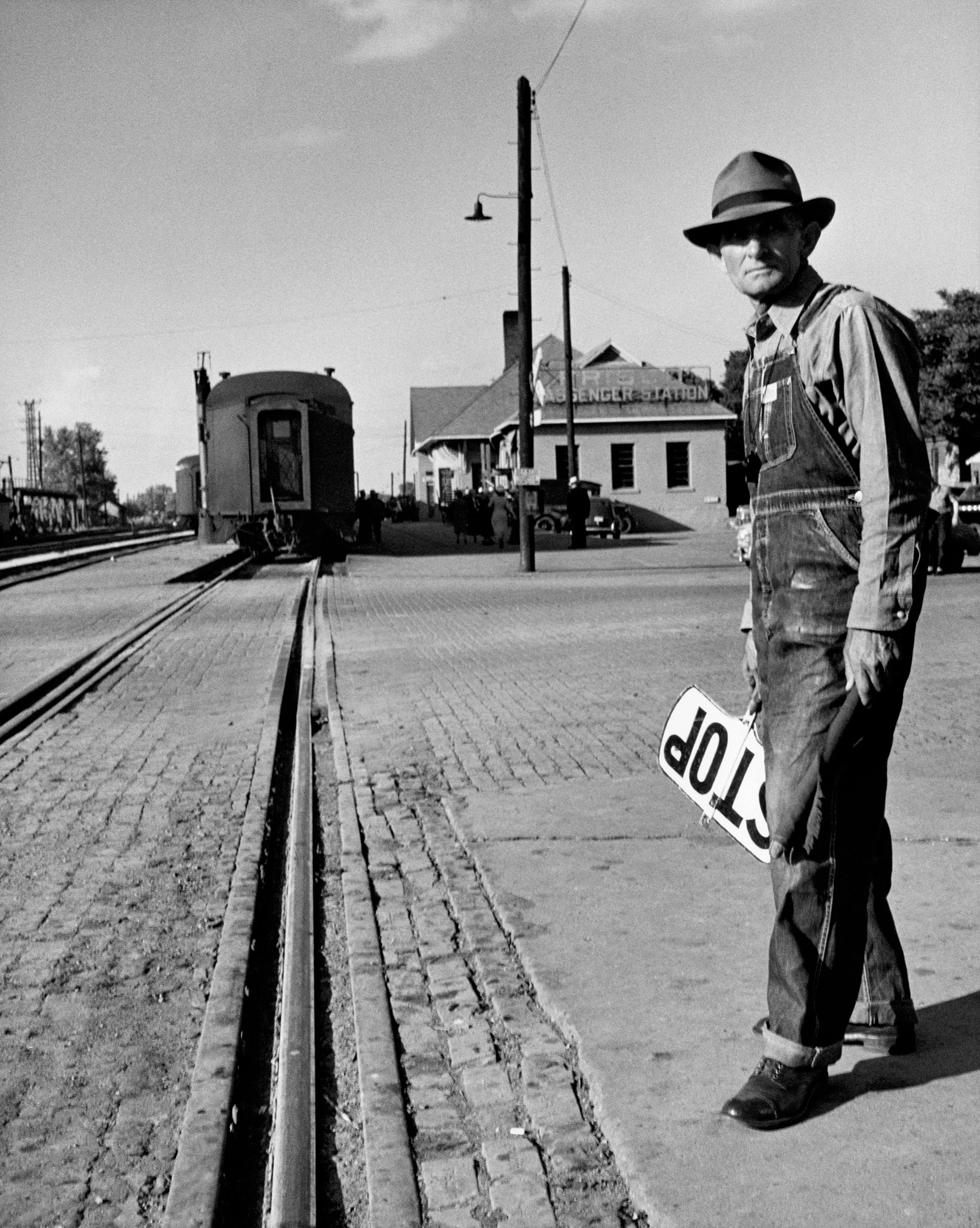

When Gordon Parks left his hometown of Fort Scott, Kansas, at the age of 15 in 1928, it was to escape a place he would later call “the mecca of bigotry.” Parks’ mother arranged for her son, the youngest of her 15 children, to live with an older sister in Minnesota, where, she hoped, Gordon would be spared the “bitter trials of Kansas.”

At 37, Gordon Parks returned to Fort Scott, sent by LIFE to photograph the bitter trials of Kansas that his mother had wanted him to escape. But his pictures would never be published, bumped from the magazine by stories deemed more newsworthy.

Now these rarely seen photographs are making their public debut in an exhibit, Gordon Parks: Back to Fort Scott, at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, which opens on Saturday, Jan. 17, as well as a book of the same name, forthcoming in June 2015. All but lost for more than half a century, the story behind the photographs is now being told for the first time.

There were plenty of places Parks could have chosen to go when LIFE assigned him a photo essay on school segregation in 1950. But he decided to train the camera on his own experience in an all-black school in Kansas, a front in the country’s growing battle over school segregation (the “Board” in the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision was that of Topeka, Kansas, a two-hour drive from Fort Scott). After a 23-year absence, Parks returned to Fort Scott to find and photograph his classmates from the Plaza School.

That wasn’t so easy. When Parks arrived, he found that all but one of his classmates had moved away. As he wrote in a partial draft meant to accompany the story—a finished version, if it existed, never surfaced—“My classmates from Plaza had drifted as if with the winds. The reports were varied concerning each; so varied that I decided to chart their course and find where they had dropped anchor.”

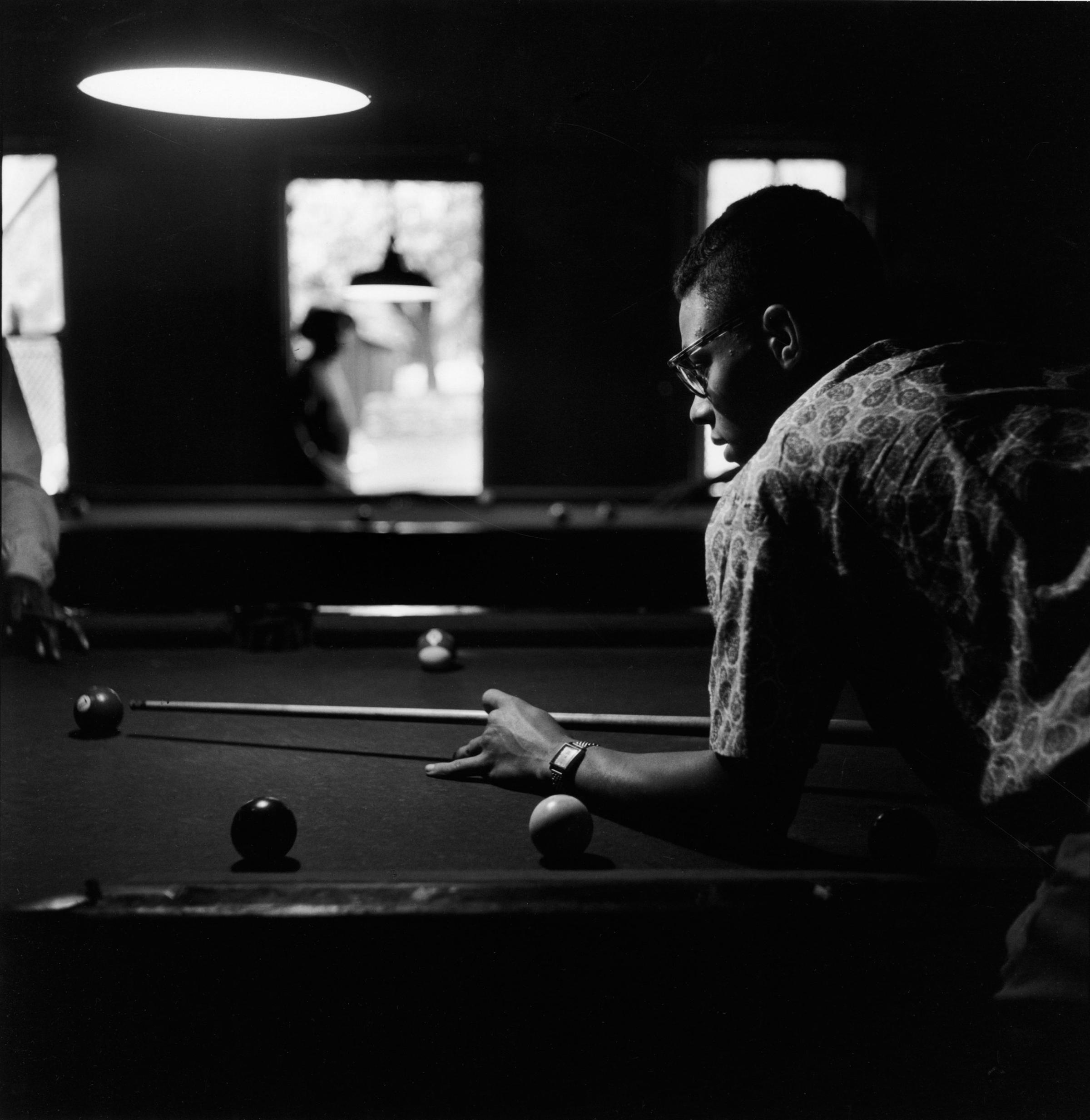

As he traveled the Midwest to find them, the story’s focus shifted, from the ill effects of school segregation to the faces of the Great Migration. Between 1910 and 1970, 5 to 6 million black Americans moved from the South to the North and West, and from the country to cities, seeking refuge from Jim Crow and work in industrialized urban centers. A handful of those millions were Parks’ schoolmates.

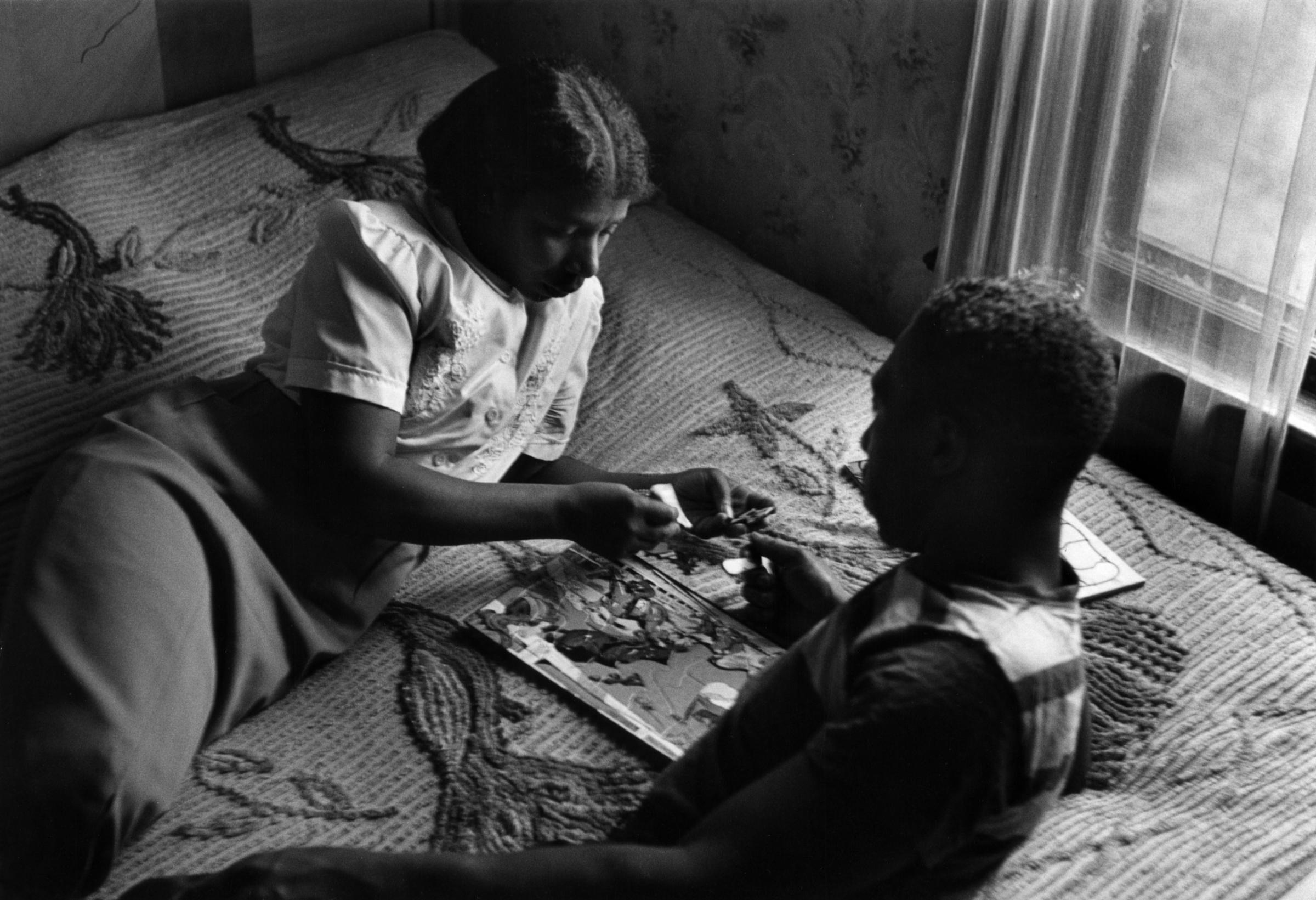

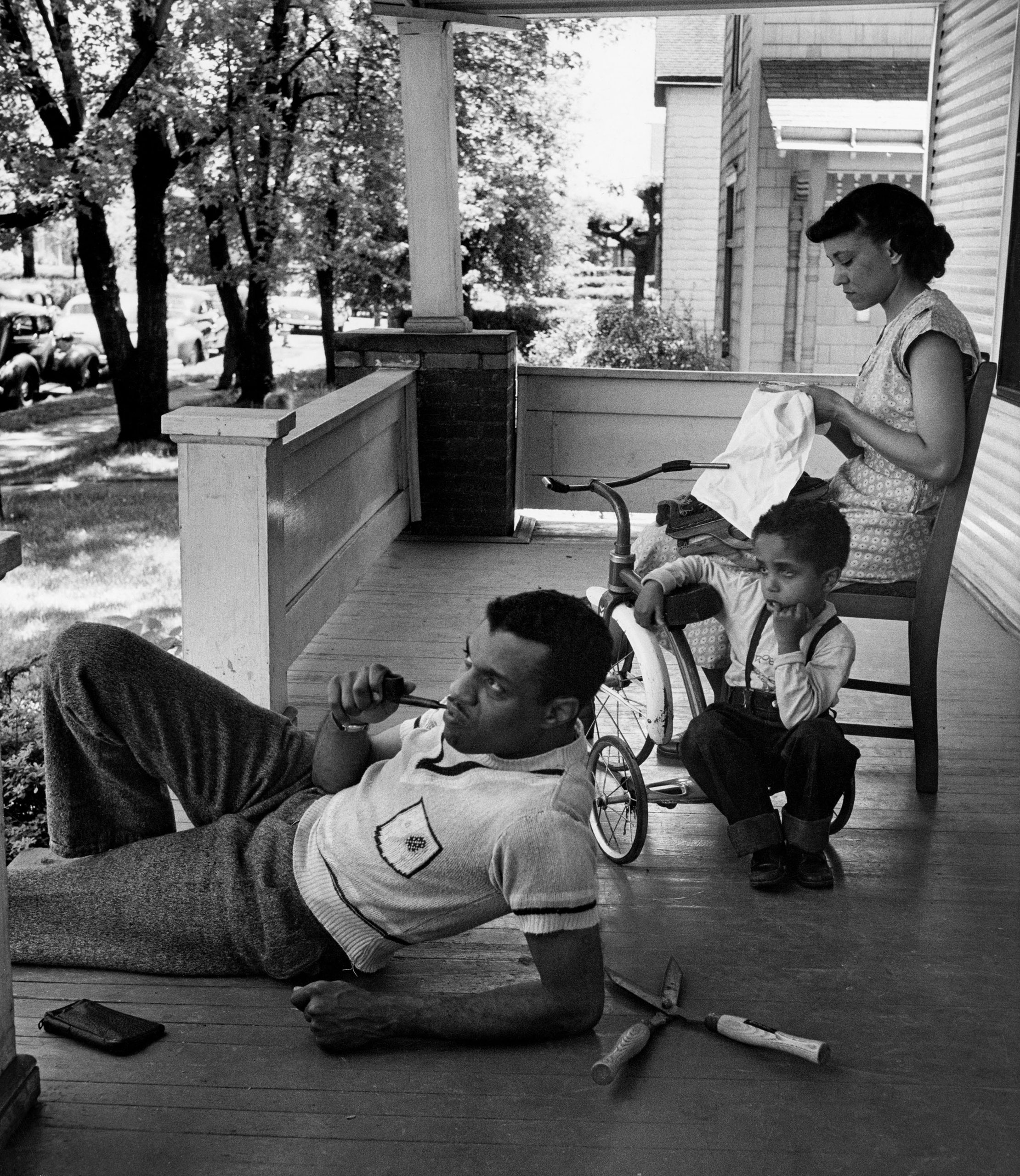

The varied reports Parks had heard proved true: He found friends who were thriving and friends who were struggling. Three classmates lived within a few miles of one another on the South Side of Chicago, then a center for African-American life. One of them, Mazel Morgan, lived in a flophouse motel with a boyfriend, who robbed Parks at gunpoint after he was through making their portrait. Another, Fred Wells, lived with his wife in a kitchenette apartment, making a living unloading boxcars for Campbell’s Soup.

One of these photographs belonged to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. While working on a book about African-American art during the summer of 2013, Karen Haas, the Lane Curator of Photographs at the museum, found herself struck by one particular image. It lacked any information about its subjects: a young couple standing in front of a movie theater on what looks to be a small town’s main street.

Haas pored over Parks’ catalogs and came up empty-handed. With the help of the Gordon Parks Foundation, Haas found herself on an expedition to Kansas, leading her to Wichita State, which has a collection of materials related to Parks, including photographs and documents about the Fort Scott assignment.

“When we were going through the boxes and we realized what we had,” says Lorraine Madway, Ph.D., Curator of Special Collections and University Archivist at the Wichita State University Libraries, “I knew that this was one of those special moments that an archivist has, when you know you have found the gold.”

The first time the story was slated for publication—Parks later wrote that the piece was meant to be a cover story with a 12-page spread—it was likely bumped by the news of the U.S. entry into the Korean War. The second time, nine months later, it was likely bumped by President Truman’s firing of General MacArthur. By that time, the story had to be fact checked again. Some of the subjects no longer wanted to participate. And many of the facts of their lives had changed in a short span of time.

In the series, Parks set out to show the breadth of the African-American experience.

“It really would have been something of an antidote to the emphasis on the downtrodden, the damaged, the gang member that so many of the stories in LIFE otherwise were about,” Haas says.

By showing his classmates in their Sunday best or spending time as a family around the piano, Parks sought to offer LIFE’s readers pictures of African-American life that reflected their own experiences. By posing his subjects in the style of Grant Wood’s “American Gothic,” Parks emphasized their dignity.

“A great storyteller is somebody who cares about his characters, who understands what makes them tick,” Madway says. “He genuinely wants to understand them, but he’s not just a reporter, he’s a participant in their lives. He reaches out and he cares about the characters and the people in his world.”

Parks discovered photojournalism as a waiter on the Northern Pacific Railway. Passengers would leave behind their magazines, and Parks studied pictures made by Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange. In 1948, after following in his idols’ footsteps with a fellowship at the Farm Security Administration, he walked into the offices of LIFE and became the magazine’s first black staff photographer. “I saw that the camera could be a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs,” he once said.

Six years after his visit to Fort Scott, Parks traveled to the outskirts of Mobile, Alabama, where he photographed an African-American family, depicting its experience of segregation there. LIFE did publish those images, in September 1956, in the form of a 12-page color photo essay titled “The Restraints: Open and Hidden.” The family Parks featured in that story was that of Mr. and Mrs. Albert Thornton. Thornton was a sharecropper and the son of a slave. He and his wife had nine children and 19 grandchildren.

“Although the Thorntons are thoughtful and, in private, articulate, they do not make many direct statements about segregation,” wrote Robert Wallace in the article. “This is because they fear yet another restraint—the constant fear of publicly speaking their minds.”

This fear was not misplaced. Two weeks after the article was published, the Thorntons’ daughter Allie Lee Causey and her family were intimidated into leaving their home in nearby Choctaw County. They lost their jobs and left their home behind as white citizens made it clear they were no longer welcome. A follow-up article in LIFE described the home they had left in haste: “On a bare bedroom wall between two windows hangs a calendar, still turned to the month of September.”

The assignment had been dangerous for Parks, as well. He wrote in a memoir that when two of LIFE’s editors traveled to Alabama to fetch some of the Causeys’ belongings, the town’s mayor said that if they had caught the photographer, “we’da tarred and feathered him and set him to fire.”

It’s impossible to know how the Fort Scott photographs would have landed had they gone public before today—and whether Mazel, Fred and the others would have been subjected to the same vitriol as the Causeys. But the second series, there is reason to believe, was inspired by the silencing of the first. According to Haas, the family later stated that despite the upheaval the LIFE story had brought to their lives, they didn’t regret doing it.

“They trusted Parks to do right by them.”

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com