The murders at Charlie Hebdo are a case of darkness wrapped in darkness, multiple layers of horror that have turned the local slaughter into a global trauma. There’s the hijacking of a religion, with evil committed in the name of a gentle faith; then there’s the threat to free expression, one of the best tools the civilized world has against barbarism. And, of course, there are the killings themselves, methodical executions conducted by pitiless gunmen.

Central to all of that is the mystery of the people whom police believe carried out the killings — no different in some ways from terrorists who’ve gone before them, but very different in one critical way: They were brothers. Cherif Kouachi, 32, and Said Kouachi, 34, both French citizens, were the central—and apparently only—targets in a manhunt that spread across France and enlisted the support of law enforcement experts around the world before they were killed in a police raid Friday after taking a hostage.

The drama played out at the very moment that, 3,500 miles away, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, 21, is standing trial for the Boston marathon bombing, an act of terror he is accused of committing in 2013 with his older brother Tamerlan, who was killed in a shootout with police just days after the crime.

That, inevitably, raises questions about the sibling bond itself. How do the Tsarnaevs and Kouachis compare with other wicked siblings, like Lyle and Erik Menendez, who murdered their parents in 1989 in a case that became a national obsession? Are they all merely outliers, bad characters who would have each done wrong no matter what? Or is there a particular power the sibling relationship has to hothouse the worst traits in the people who are part of it?

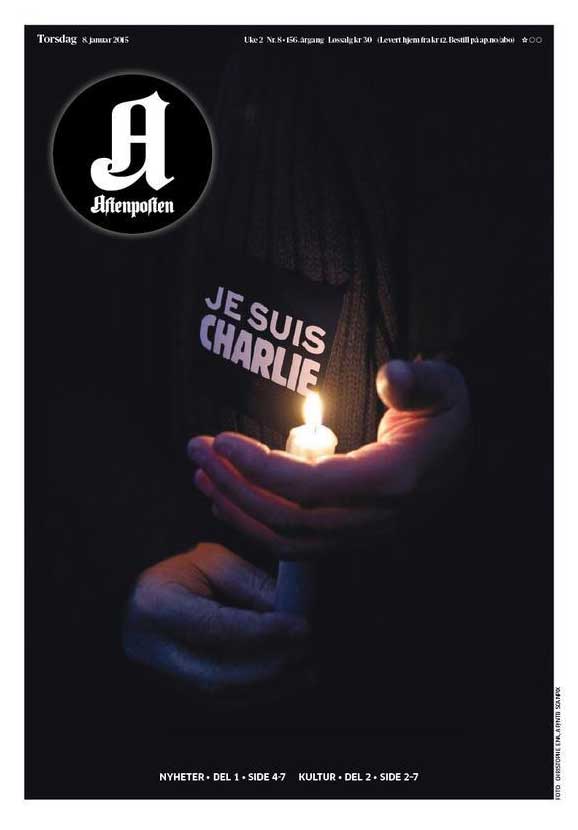

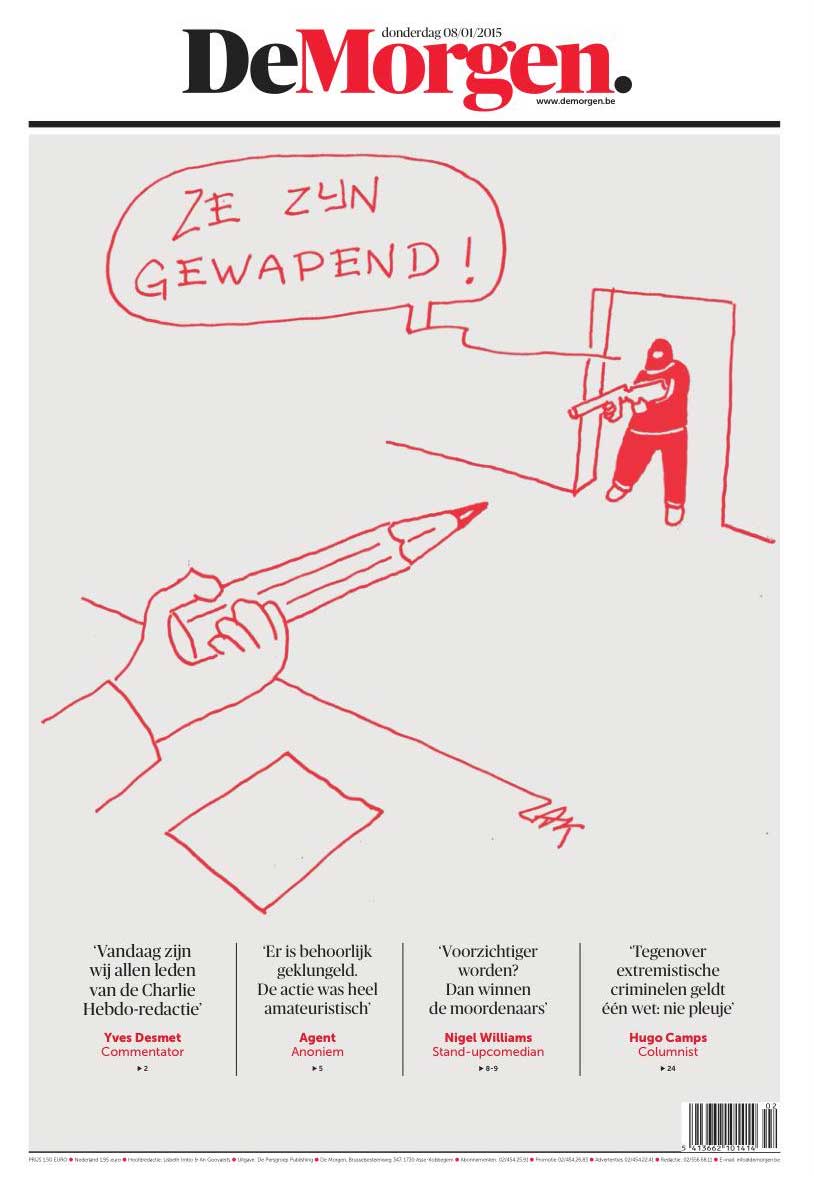

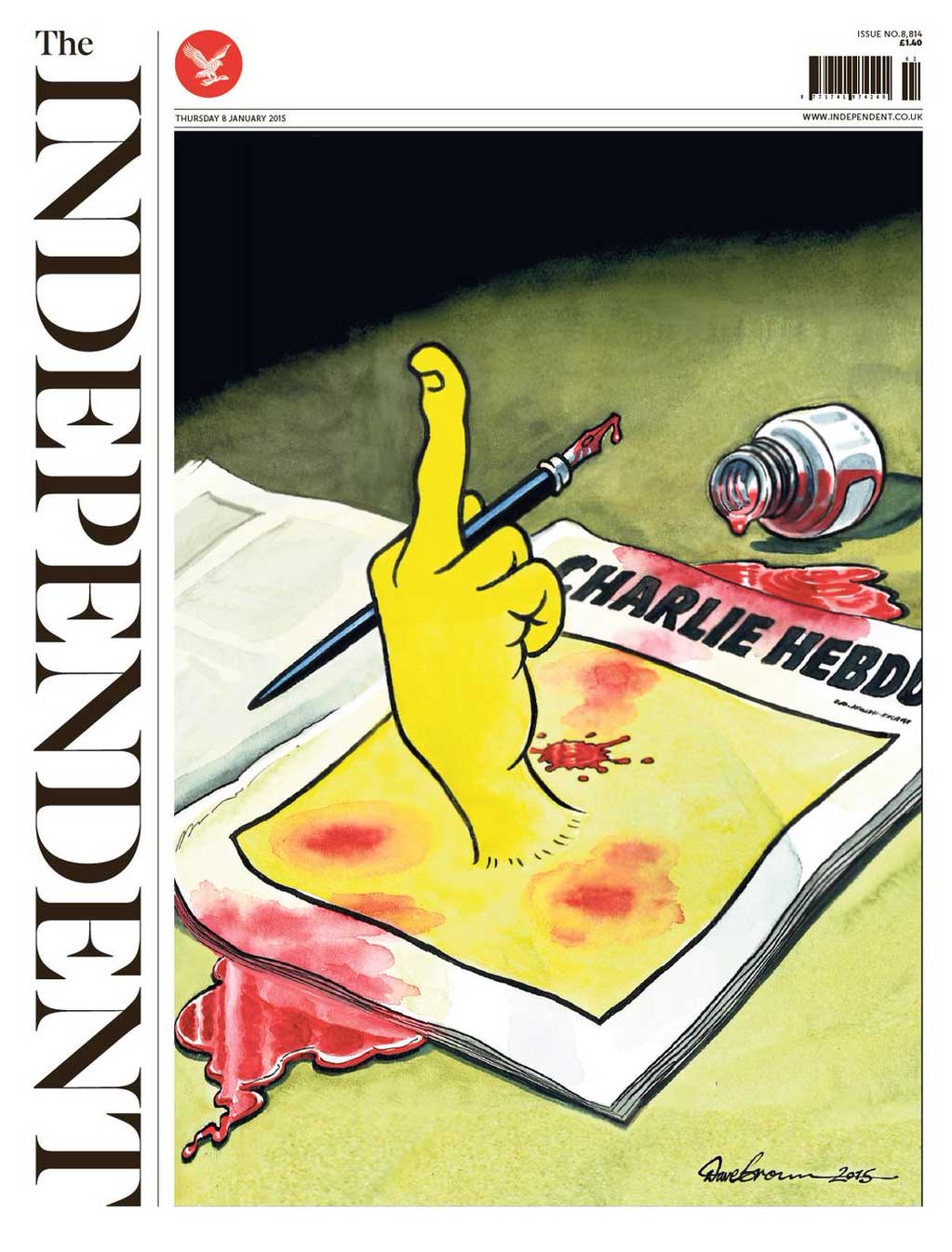

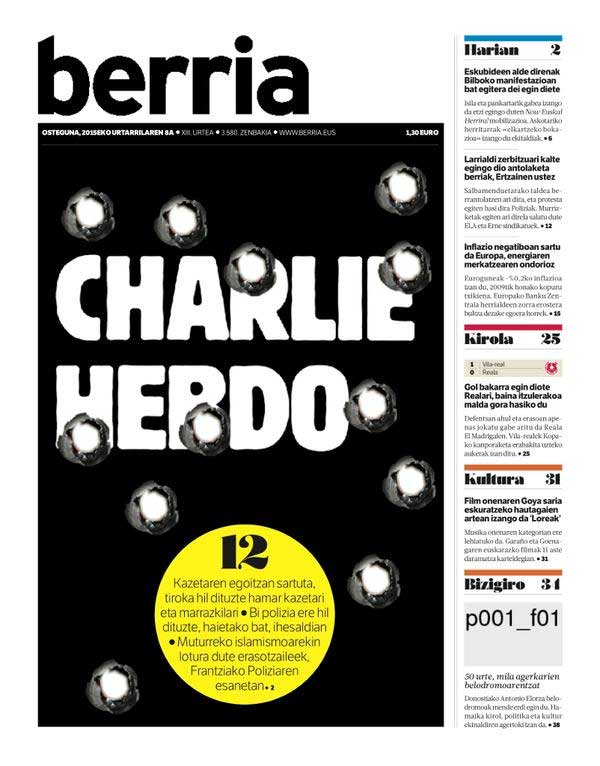

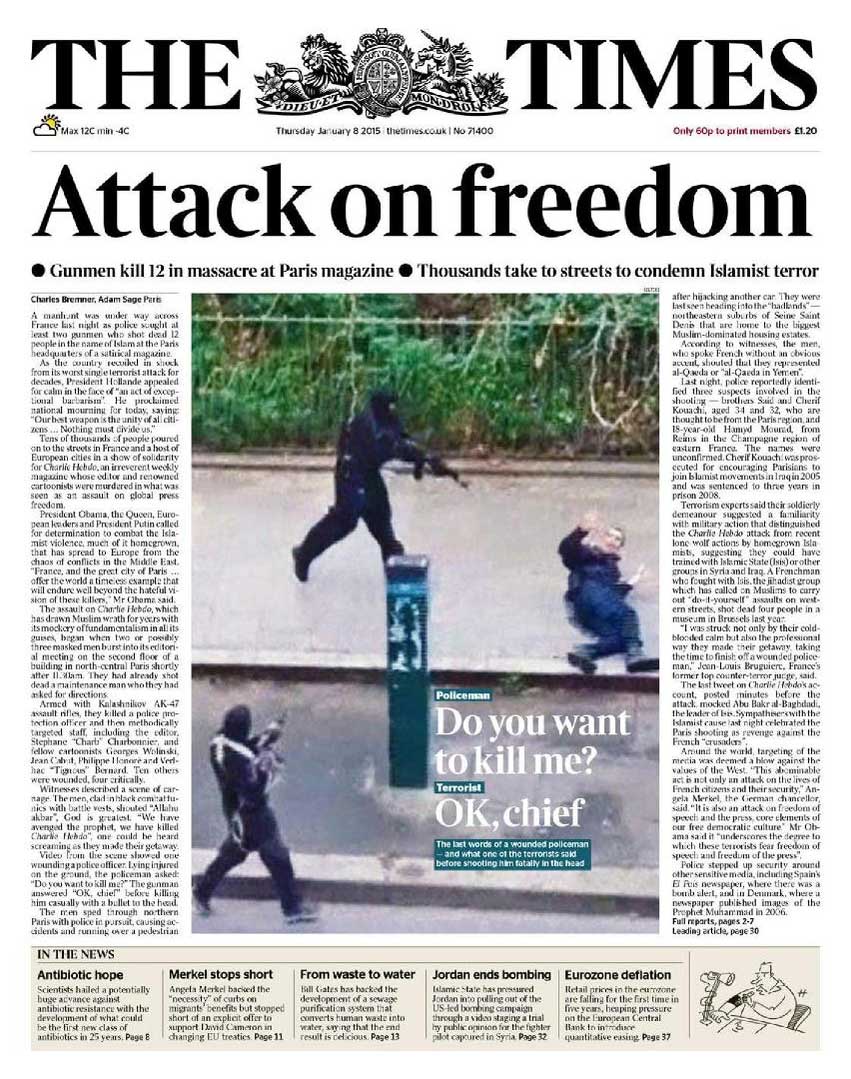

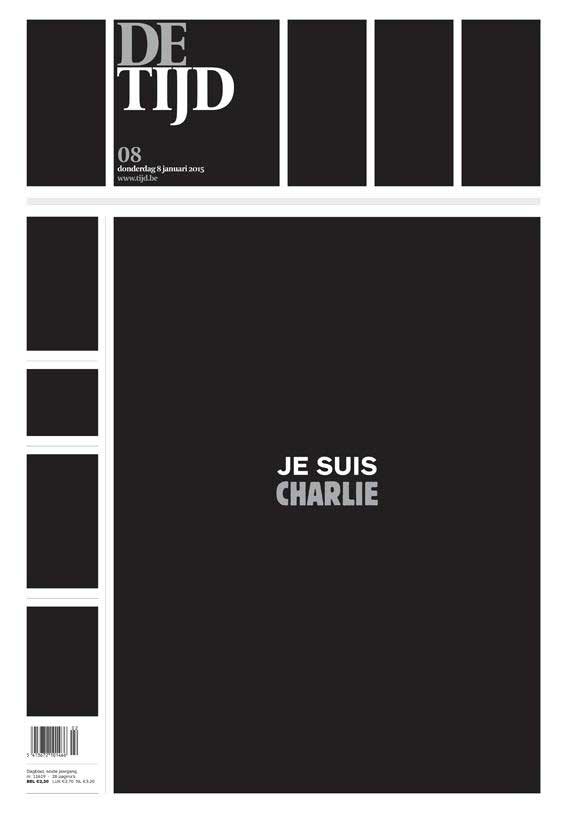

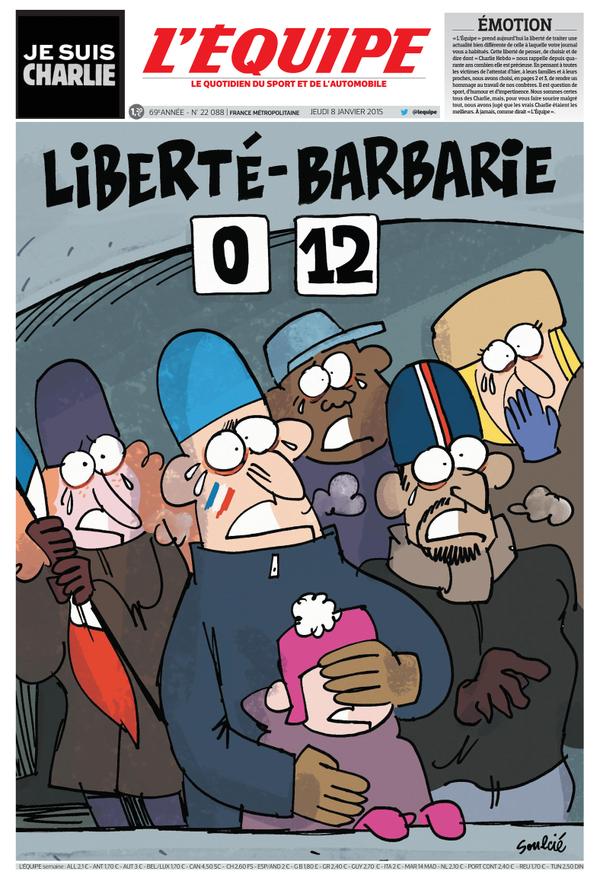

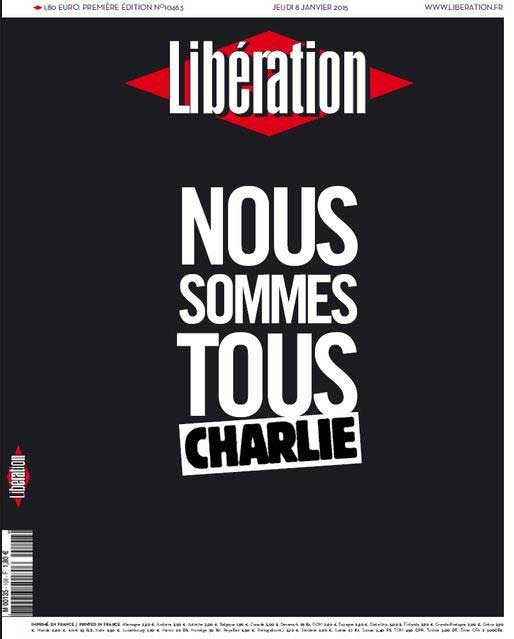

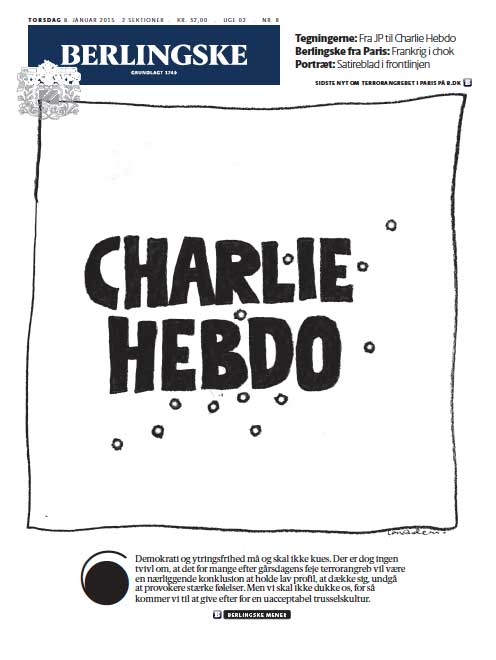

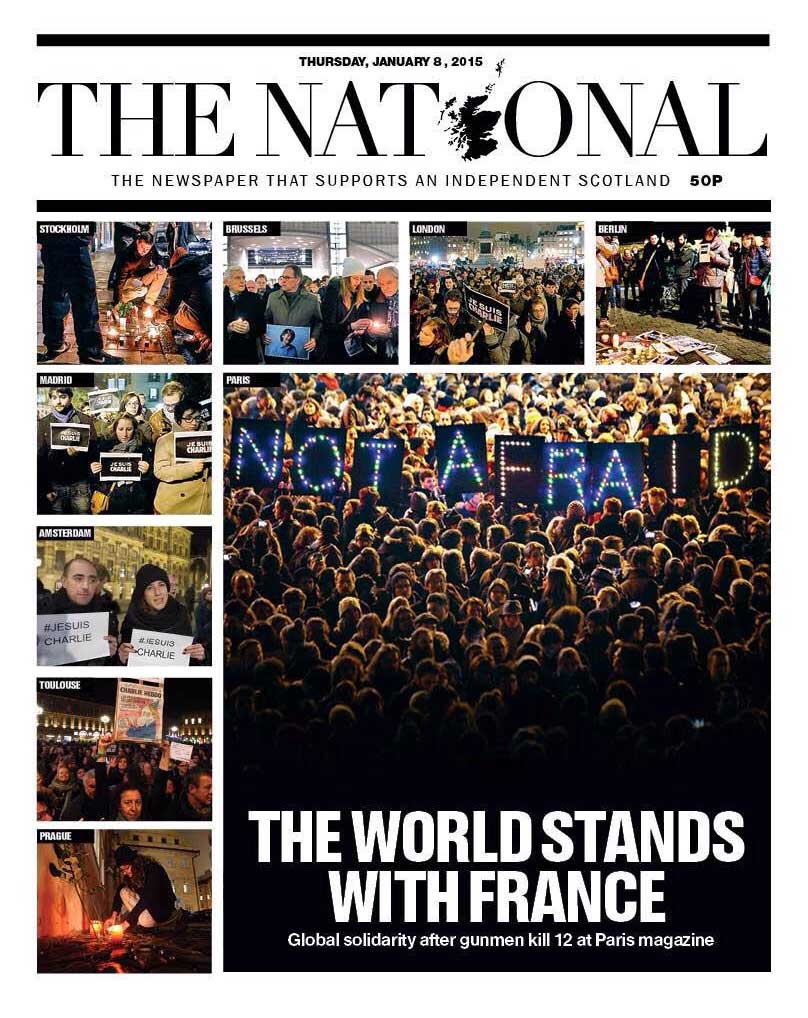

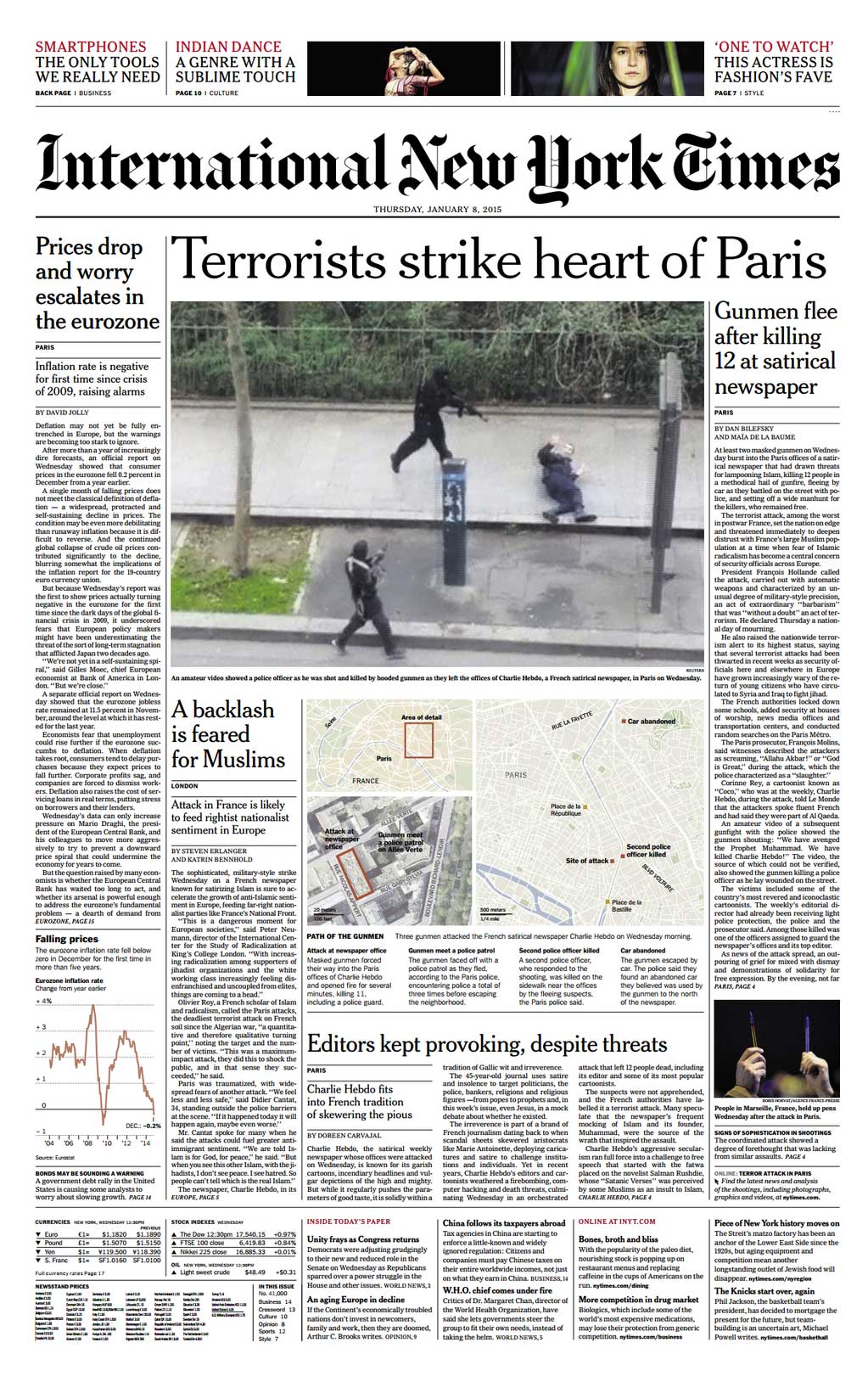

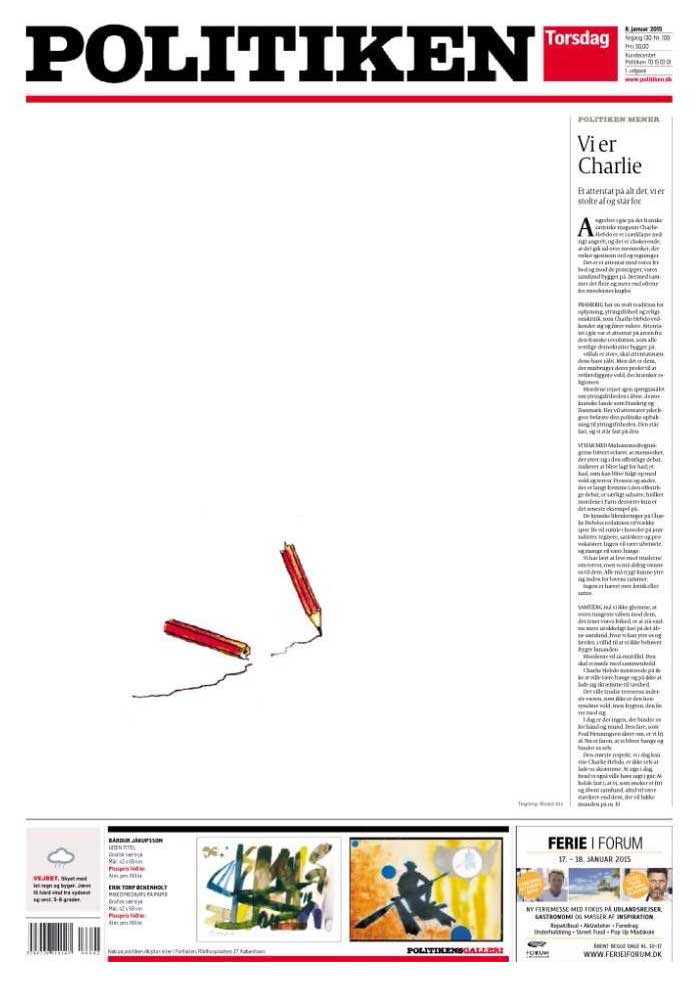

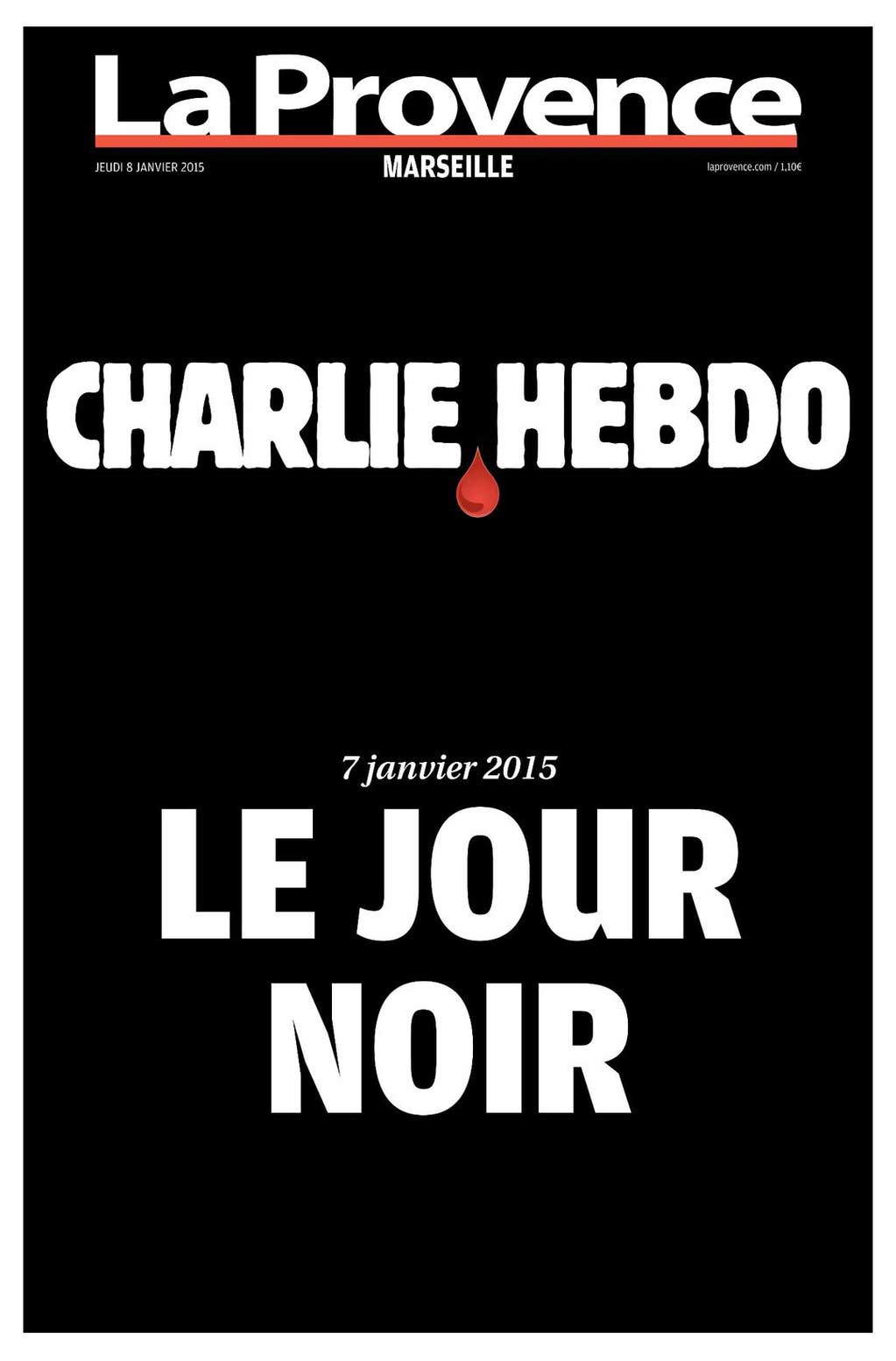

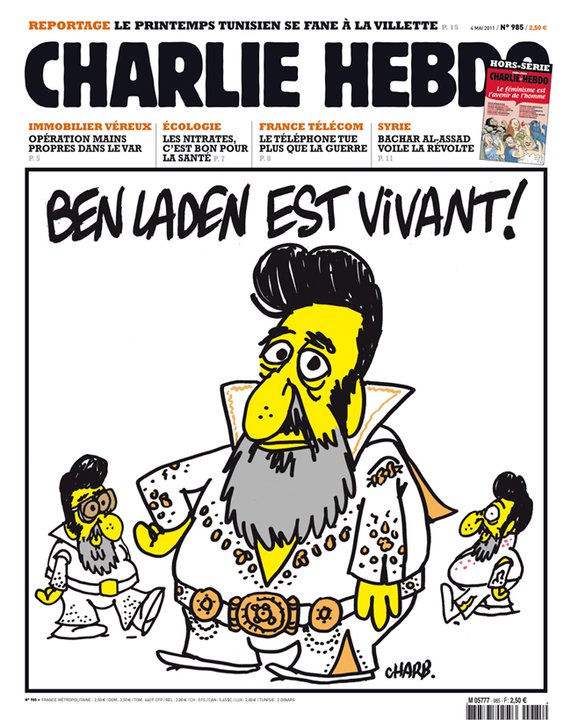

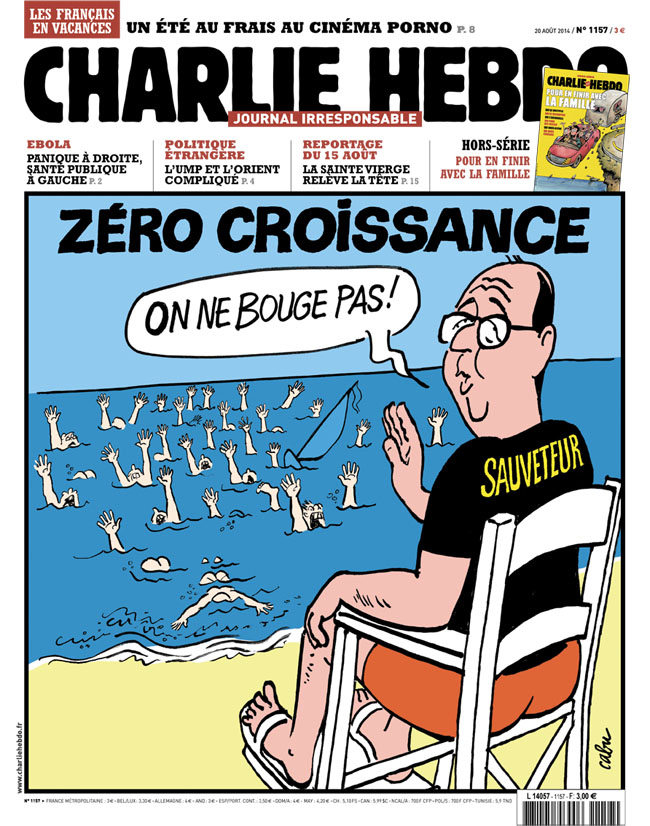

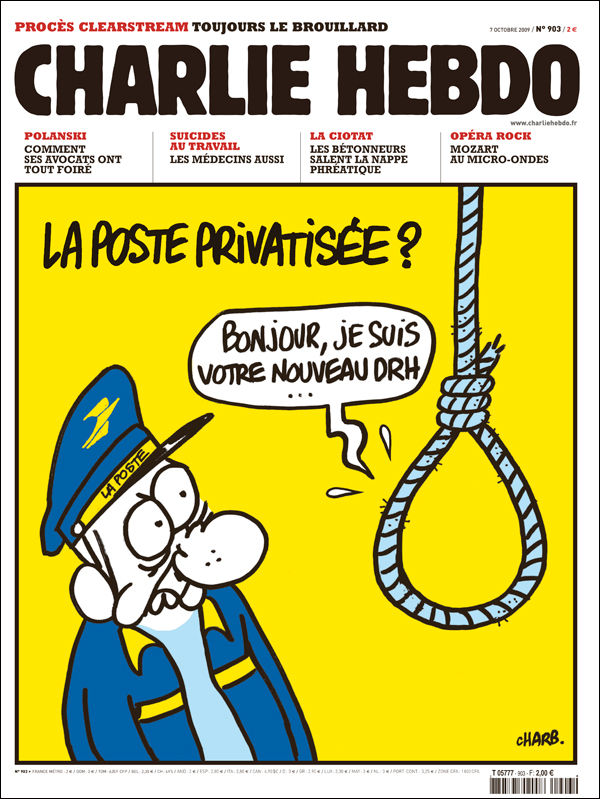

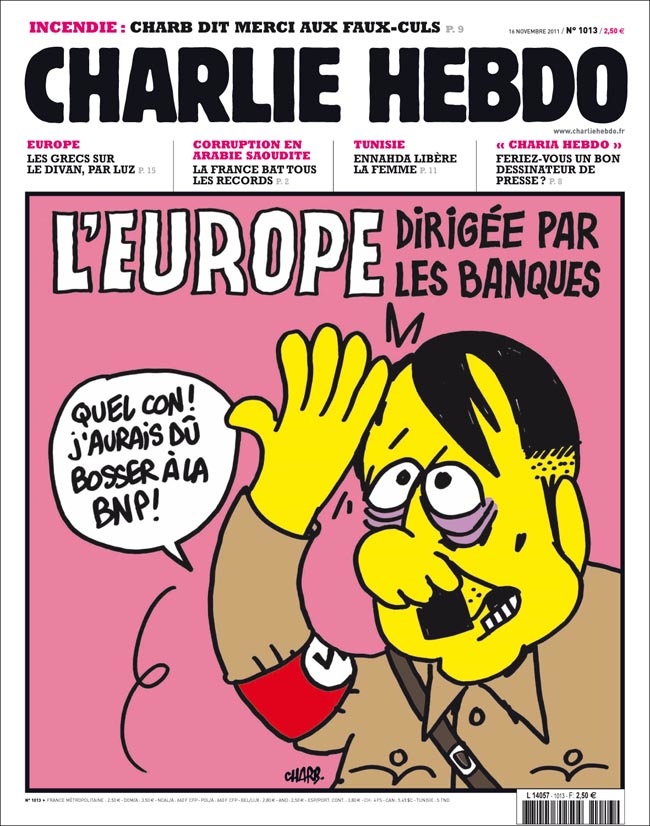

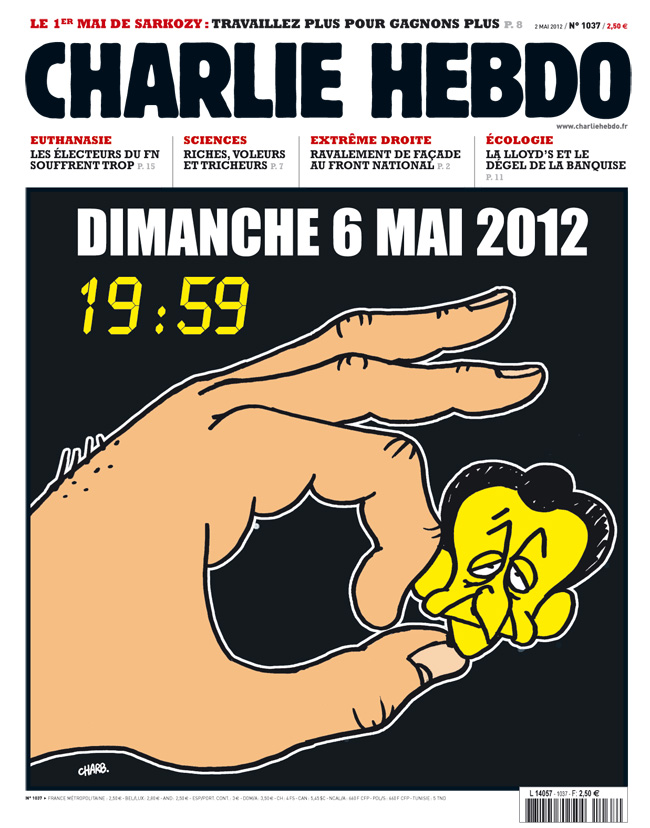

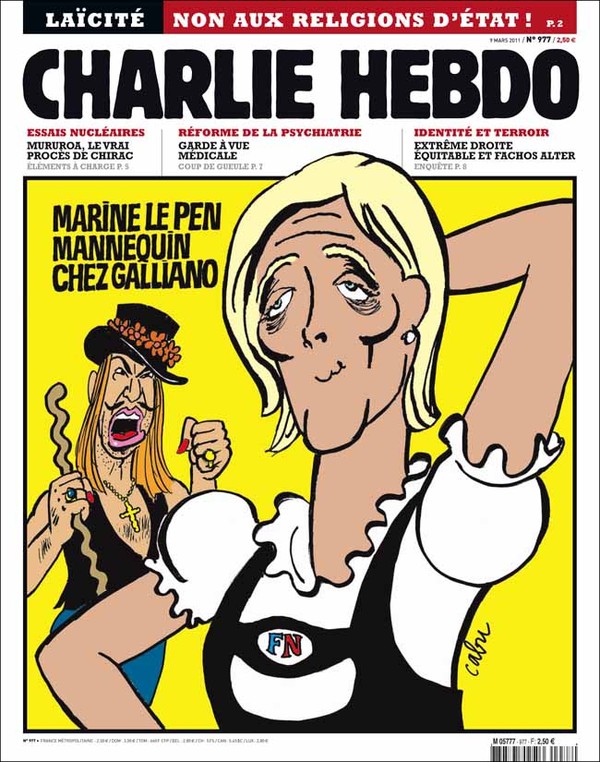

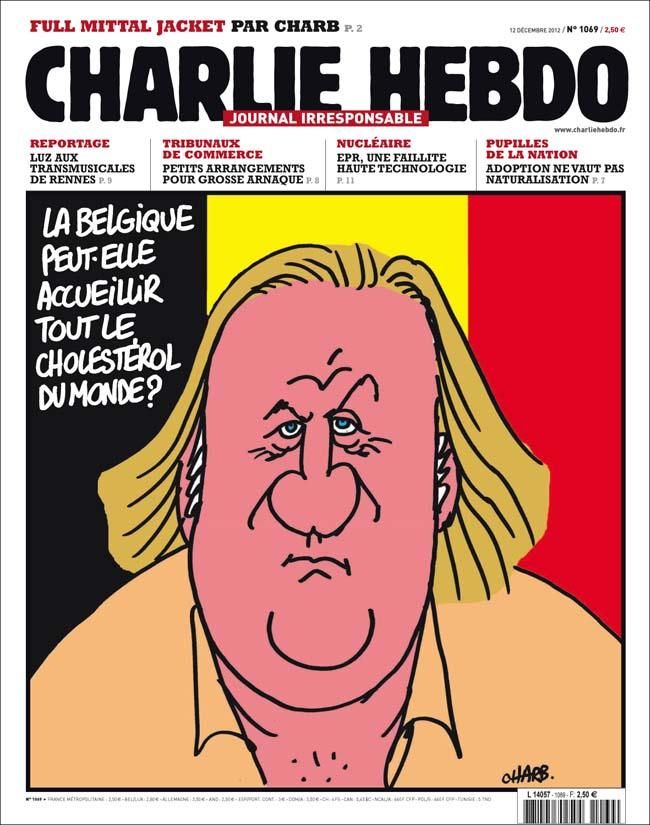

Front Pages React to Paris Terror Attack

One thing is certain: brothers and sisters influence one another’s behavior in a way that no other person in their lives—not parents, not teachers, not friends or spouses—seems to be able to, especially when it comes to bad behavior. A younger brother or sister is twice as likely to drink and four times as likely to smoke if an older sibling has already picked up the habits, according to research I reported in my 2011 book The Sibling Effect. Younger sisters are four to six times likelier to become pregnant in high school if their big sisters were teen moms first.

“Having an older sibling exposes you to things firstborns simply aren’t exposed to,” Susan Averett, a professor of economics and a siblings expert at Lafayette College, told me. “You see things you wouldn’t otherwise have seen. In some ways your innocence gets taken away.”

Smoking and drinking, of course, are behavioral misdemeanors. But older brothers and sisters can lead their little sibs into much larger crimes too. Theft, assault, drug-dealing, even murder can all be part of a sibling-to-sibling legacy that psychologists and sociologists call “delinquency training.” The hand-me-down misbehavior is more common brother-to-brother, but it’s by no means absent in sisters. More troublingly, it doesn’t take long for learned behaviors to become permanent behaviors—even if the siblings drift apart.

“Siblings train each other, they influence each other,” says psychologist Jennifer Jenkins of the University of Toronto. “A person is fashioned from all these small things.”

Even true felonies, of course, are nothing compared to what the Tsarnaevs and the Kouachis allegedly did. For that kind of savagery, you need something more—and typically that something is grievance, a shared sense of being wronged, which the siblings echo back and forth to each another, repeating and reinforcing the perceived outrage. In most cases, the influence runs from older to younger.

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, a Chechen immigrant like his older brother, was a scholarship student who wanted to study nursing and was variously described by his friends in all of the ways people who wind up doing something terrible often are—generous, compassionate, thoughtful, never showing a sign of trouble. Tamerlan, on the other hand, never quite adjusted to life in the U.S. and retreated further and further into isolation and resentment. “I don’t have a single American friend because I don’t understand them,” he complained in 2010.

But he did have Dzhokhar, and once Tamerlan began flirting with jihad in 2011, it might have been relatively easy for him to bring his little brother around—especially because no matter how well Dzhokhar assimilated in the U.S., he was still an outsider by birth, language, culture and, in the case of Chechnya, violent, religiously driven politics. Working with that emotional clay, a big brother could easily shape his little sib into nearly anything he wanted.

“When siblings are very close,” psychologist Elizabeth Stormshank of the University of Oregon told me, “that relationship becomes more powerful and meaningful and can enhance risk behavior as well.”

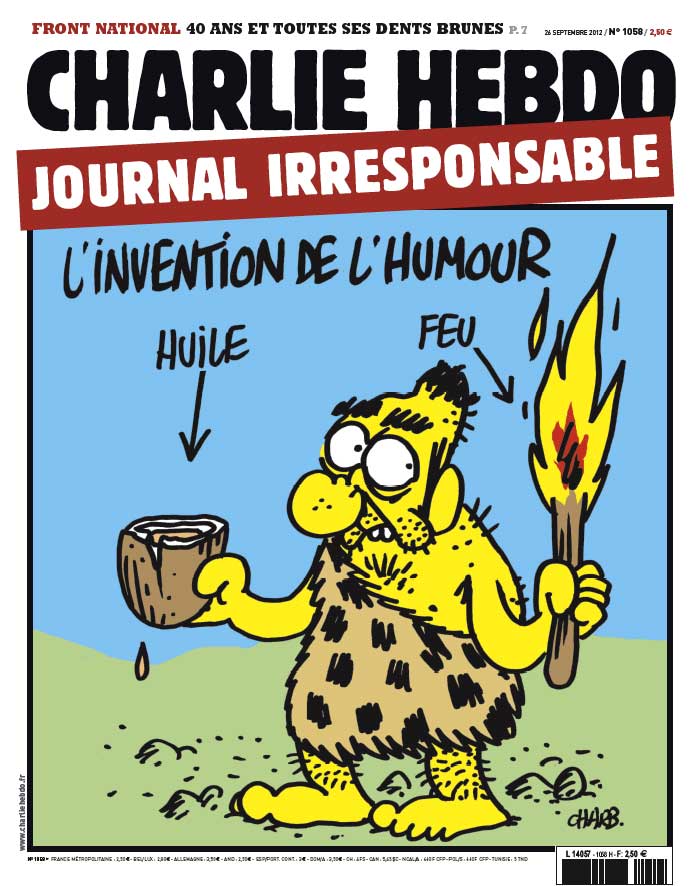

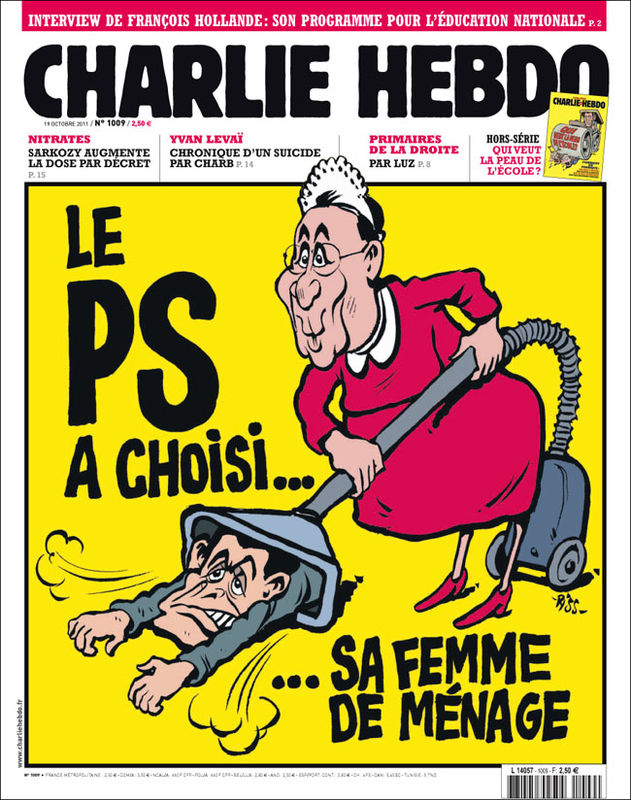

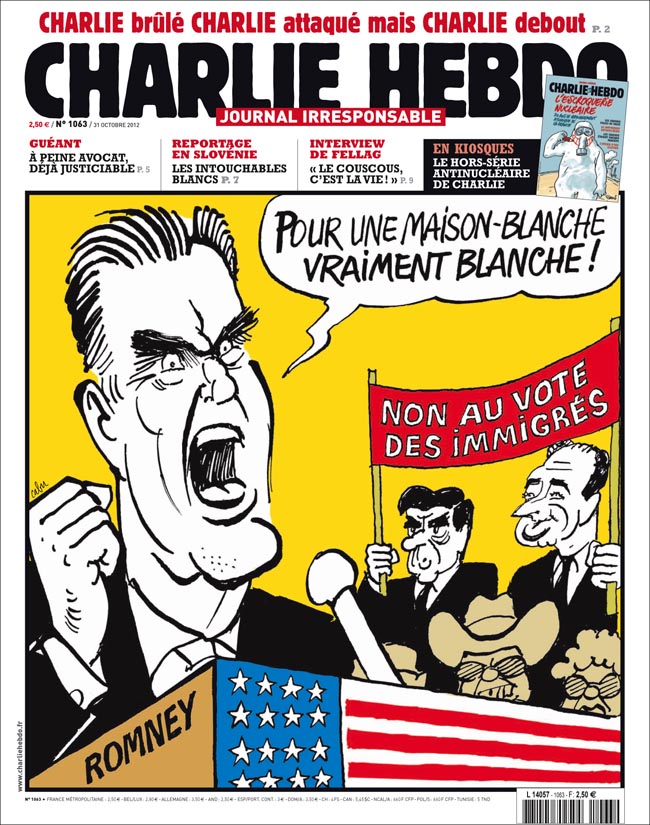

See Covers Published by Charlie Hebdo

If the Kouachis underwent a similar radicalization, early reports suggest it was younger brother Cherif, not big brother Said, who took the lead. Cherif had already spent time in prison in 2008 for being part of an organization that was recruiting jihadis, while Said’s rap sheet is said to be clean. Both brothers were in Syria within the past year, however, and might well have come back radicalized. According to a witness at the scene of the Charlie Hebdo killings, one of the masked shooters said, “You can tell the media that it’s al-Qaeda in Yemen.”

The Menendez brothers may have similarly schooled one another in grievance, sharing both a home and a hall of mirrors relationship in which they convinced each other that their wealthy parents had done them wrong and that nothing could be more just than for them to die for their crimes and lose their fortune to the sons they’d mistreated. Indeed, the idea that they’d been abused was at the center of the failed defense the brothers mounted at trial.

Certainly, it’s not just siblings who can share a poisonous—and ultimately murderous—relationship. John Allen Muhammad and Lee Roy Malvo, the Beltway snipers who terrorized the Washington metropolitan area in 2003 weren’t brothers. Nor were Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, the Columbine killers. But in both cases there was a dominant partner—very similar to an older sibling. Muhammad was much older than Malvo—41 at the time of the killings compared to Malvo, who was only 17. Klebold and Harris were classmates, but Harris was the far stronger, far more lethally charismatic personality, someone who would likely have turned out a monster no matter what. Without Harris, Klebold may have had a chance.

It’s way too early to say anything with certainty about the Kouachis’ relationship. Even if both survive the ongoing manhunt and are captured, it may be impossible to unravel their shared pathology. It matters—some—to try, because understanding the mind of evil may help prevent such crimes in the future. But in some ways the effort is irrelevant. The 12 people killed in the Charlie Hebdo attack are never coming back; the 11 people who were injured can never be fully uninjured. It is a sad fact of this latest human atrocity that the sibling relationship—which can be one of the richest and most nurturing of all—may have been the source of so much suffering.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com