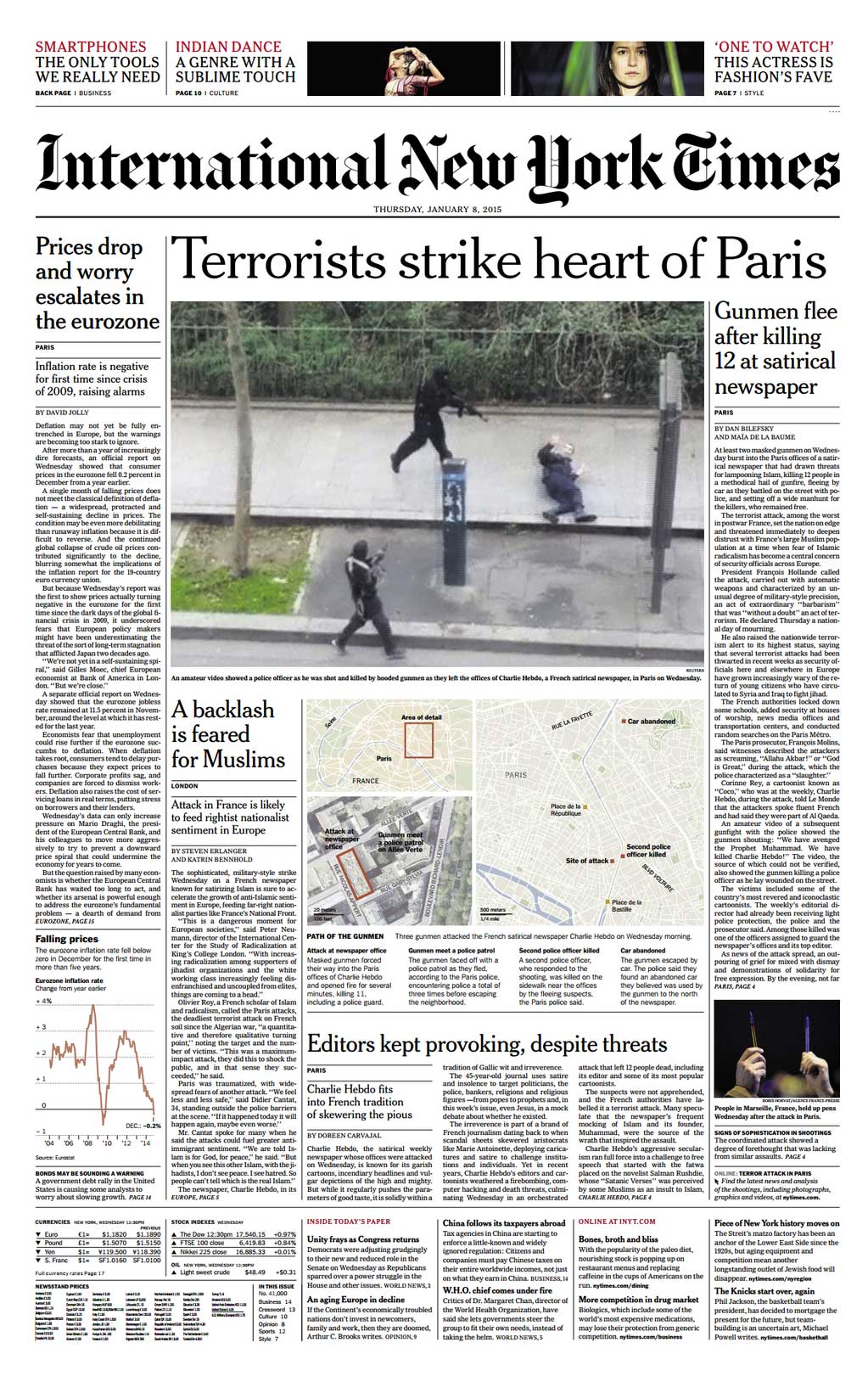

With news that the chief suspects in the massacre on Wednesday at the offices of the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo are French citizens, a new mystery emerges: how could the land of liberty, equality and fraternity have produced men hell-bent on destroying all three? While the attack may evoke comparisons to earlier tragedies in New York, London, or Madrid, France’s relationship with its Muslim citizens is particular — and particularly fraught. What sets France on a particular collision course with Islamic practices is the country’s radical brand of secularism — and this ideology’s impact on French Muslim life.

With more than 5 million Muslims, France may have Western Europe’s largest Muslim community, but its relationship with Islam has been tenser than, say, Britain’s or Germany’s. An older generation of French Muslims has been alienated by memories of the Algerian War in the 1950s, when local groups battled for independence from more than a century of French rule, with its heavy-handed disdain for local customs. Their children and grandchildren frequently feel excluded from mainstream society because of their Arabic names or the color of their skin.

Such feelings may be shared by other European Muslims, but French Muslims face not just social hurdles, but an officially-enshrined hostility to public displays of faith. Having fought its revolution, in part, to keep priests from meddling in state affairs, France has a passion for keeping church and state separate. “Secularism,” states france.fr, France’s official information website, “is a French invention.” Where the French cherish the neutrality of the public realm, free from any religious symbolism, mainstream Muslim culture embraces public declarations of religiosity through the veil or the call to prayer. France’s cherished codes of secularism clash with the public nature of the practice of Islam, a faith that in Muslim-majority countries is stamped on public life, from politics to laws to the wearing of beards and veils, or breaking for prayers in the middle of the work-day.

France prefers its faiths kept private: its 1905 law on the separation of church and state was the legal basis for the much-contested 2004 ban on veils, crosses and yarmulkes in schools. The veil debate pitted Muslim women’s desire for self-expression against the core French values of equality and universalism, noted Princeton political scientist Joan Wallach Scott in her book The Politics of the Veil. Supporters of the ban, wrote Scott, believed veils chipped away at the French ideal of “the oneness, the sameness of all individuals,” under the Tricoleur.

For many Muslims, it’s the official insistence on oneness and sameness that rankles. In 2008, a French court denied a Moroccan woman French citizenship on the grounds that her veil and her submissiveness to her husband were “assimilation defects.” Though the New York Times reported “almost unequivocal support for the ruling across the political spectrum,” one Muslim leader told the paper he worried the decision set a precedent for arbitrary decisions of what constitues a radical Muslim lifestyle. In 2010, the French Senate banned public wearing of face-coverings, including the Muslim face-veil, the niqab. And in 2013, the government launched what it called a Charter for Secularity in School, a set of guidelines on 15 key points of secularism to be posted in classrooms as an attempt to keep religion out of school. The then-government education minister, Vincent Peillon, insisted it was an attempt “to get everyone together,” but it had the opposite effect, with Muslim leaders claiming it stigmatized their community.

France Stands in Silence for Terror Attack Victims

The focus on the Charlie Hebdo murderers, and their spurious claims to be acting as pious Muslims, will obscure the fact that the vast majority of French Muslims embrace the Republic’s legal and cultural norms. As French scholar Olivier Roy has pointed out, France’s Muslim organizations are using legal proceedings, not violence, to challenge what they see as institutional discrimination.

But in fearful times, the loudest and shrillest voices tend to prevail. The massacre occurred on the publication day of a new novel by controversial writer Michel Houellebecq. In the novel, Submission, Houellebecq, who appeared in cartoon form on the cover of the latest issue of Charlie Hebdo, imagines France in 2022 as a country with a Muslim president, legal polygamy and the Quran required on university syllabi. Houellebecq told interviewers that his vision of an Islamic France was potentially “realistic,” and Marine Le Pen, leader of the right-wing National Front agreed. As Le Pen hones her anti-migrant, anti-Islam platform for the 2017 elections, the Charlie Hebdo massacre will only serve to help her cause.

As for those French who are both law-abiding and Muslim, the challenge is two-fold: coping both with their own grief at the attack on their nation’s values–and with the specter of a rising tide of Islamophobia.

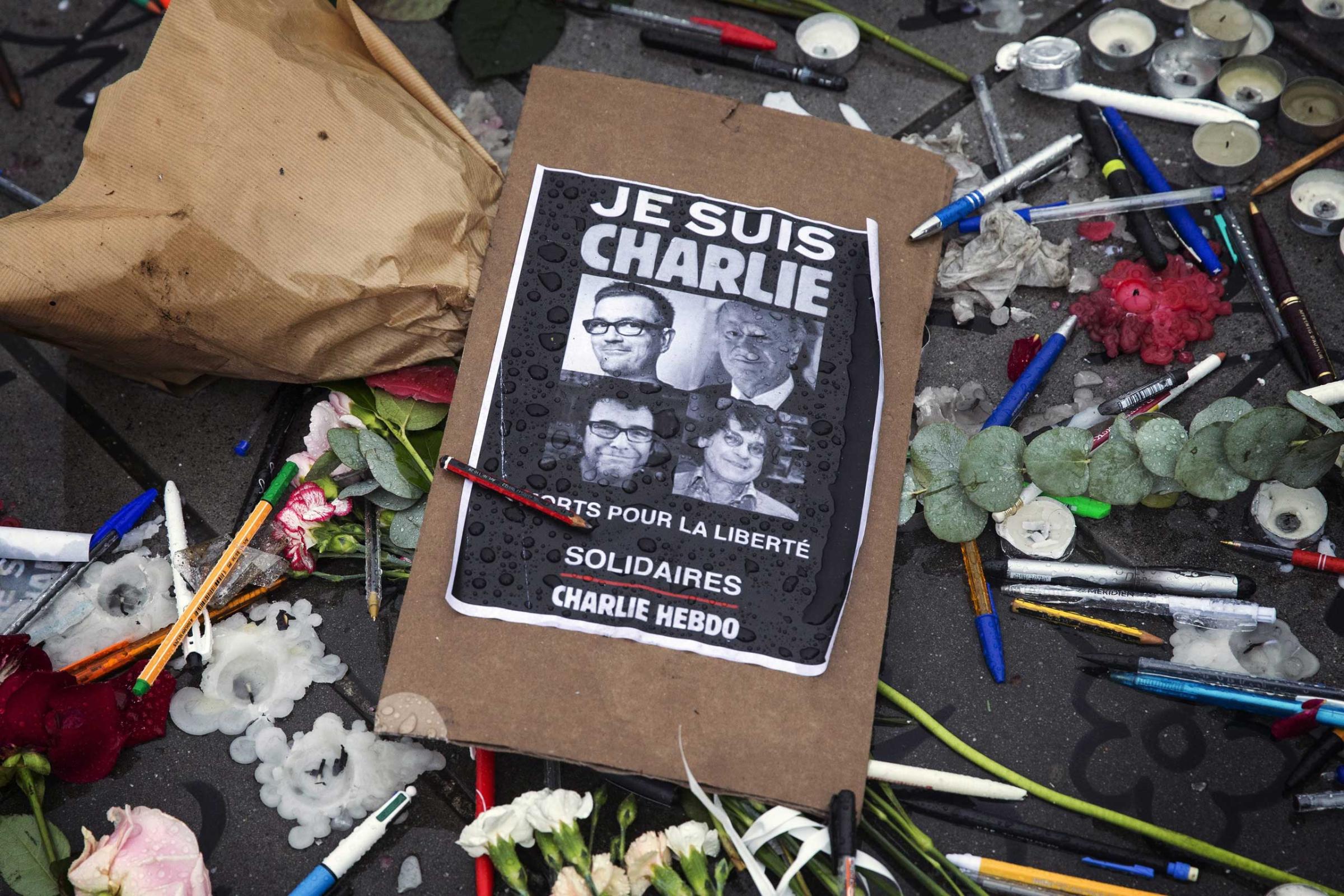

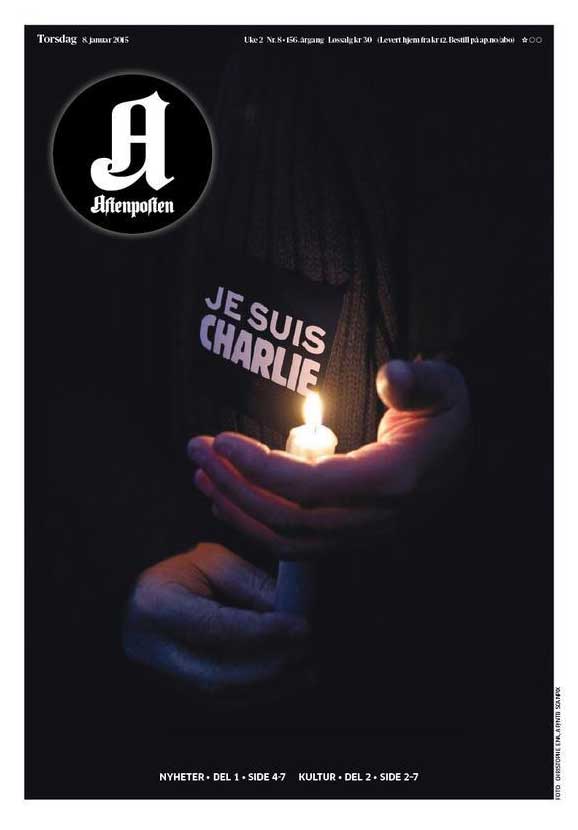

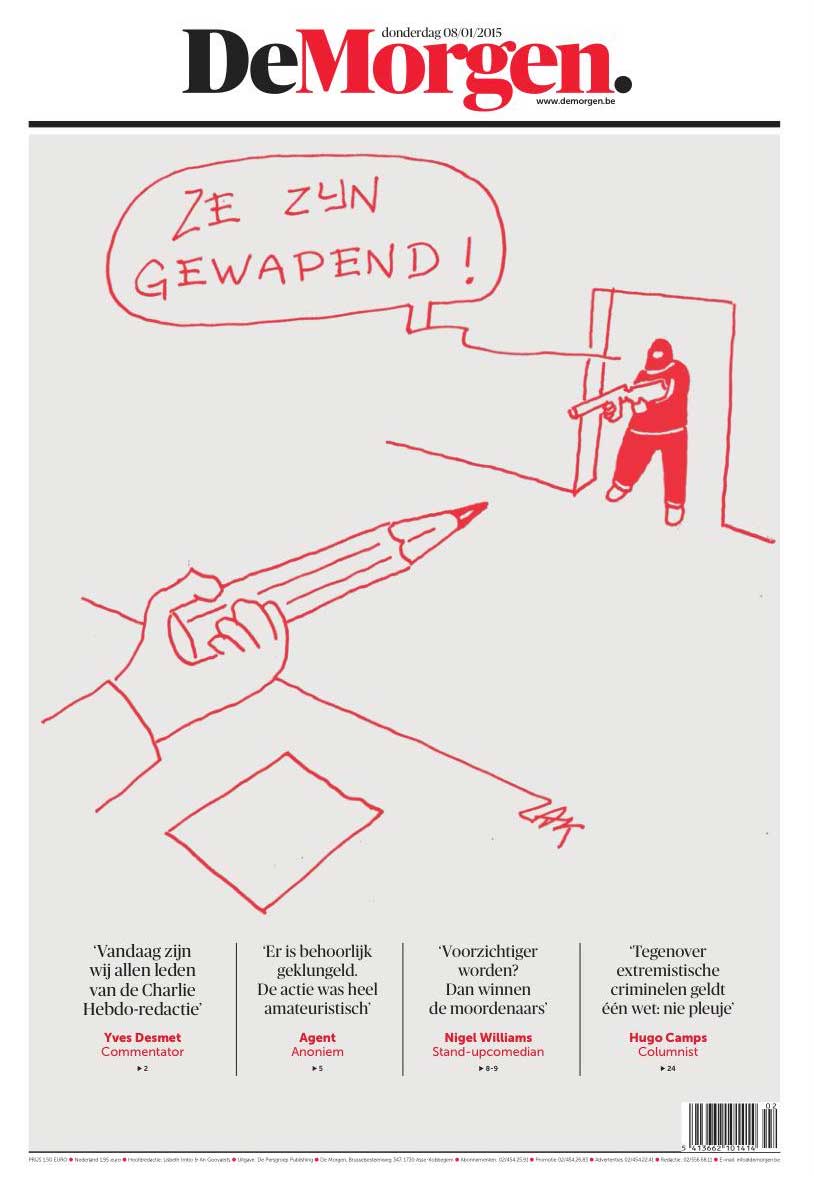

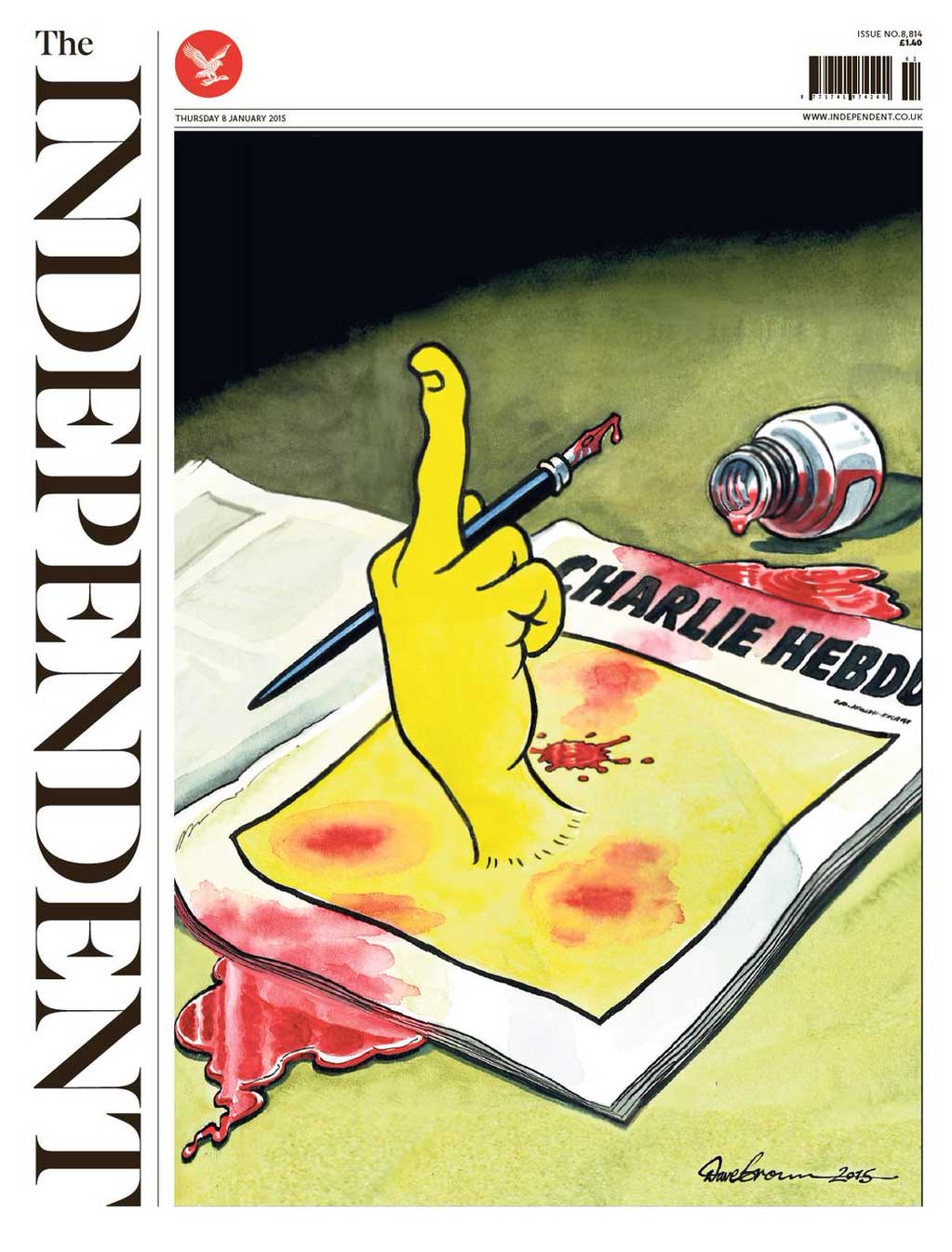

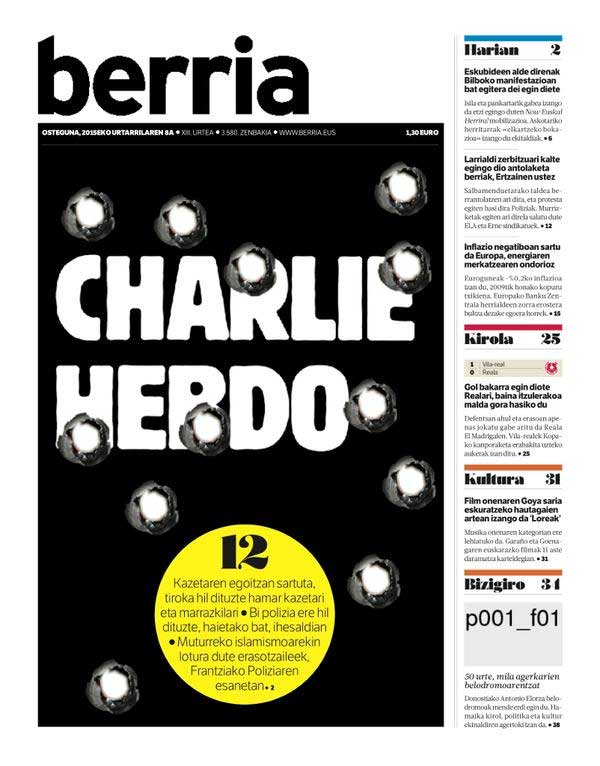

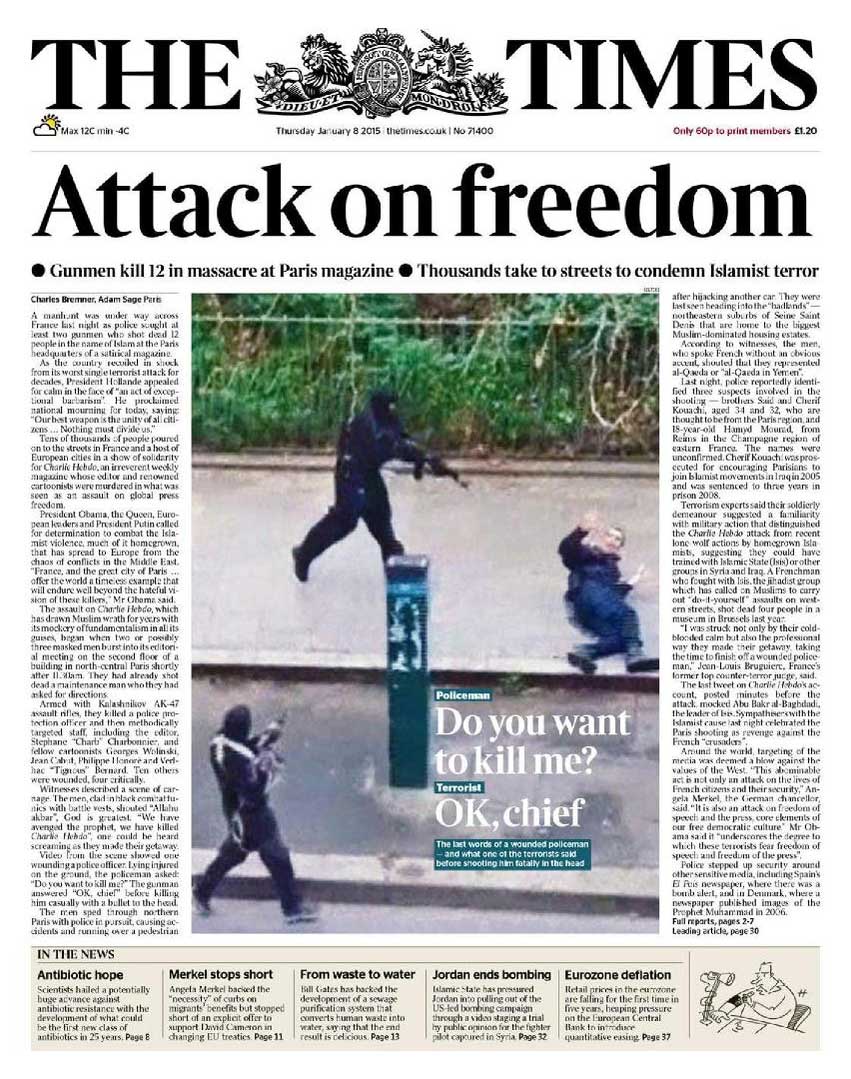

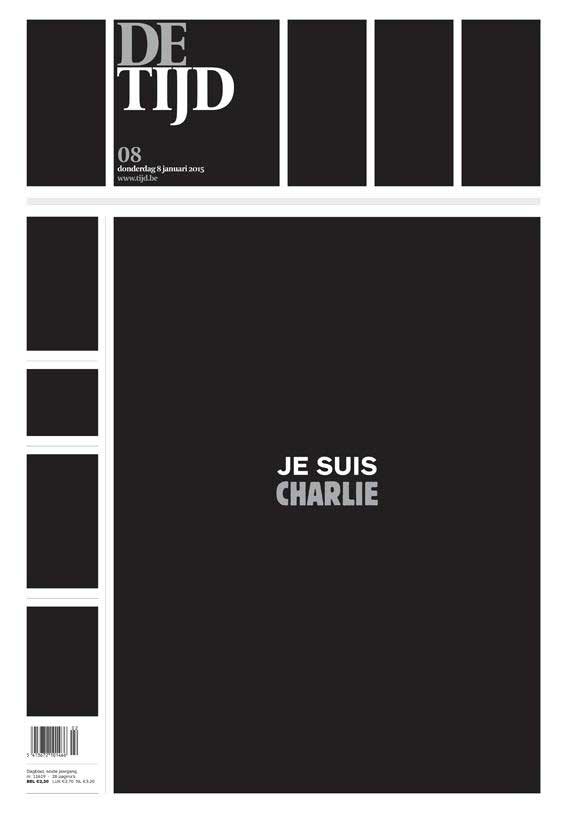

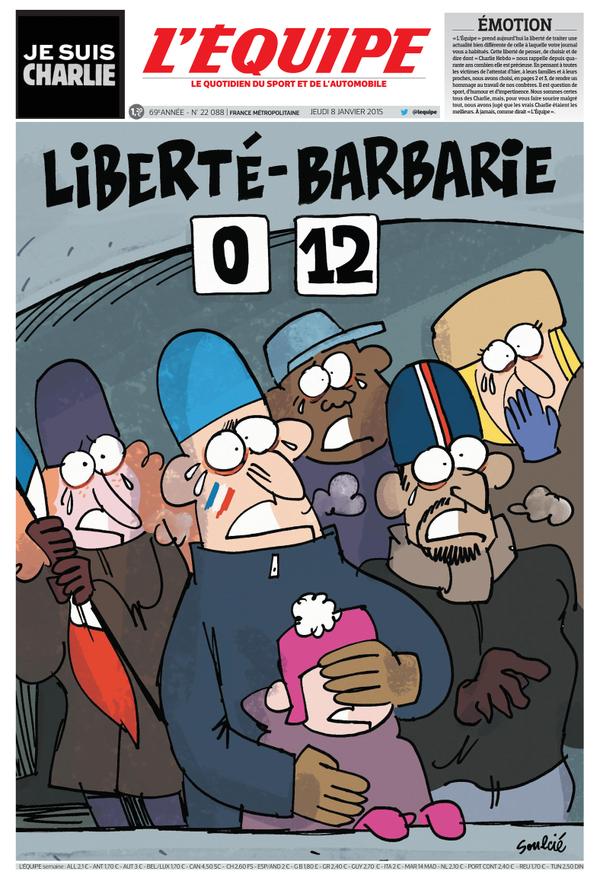

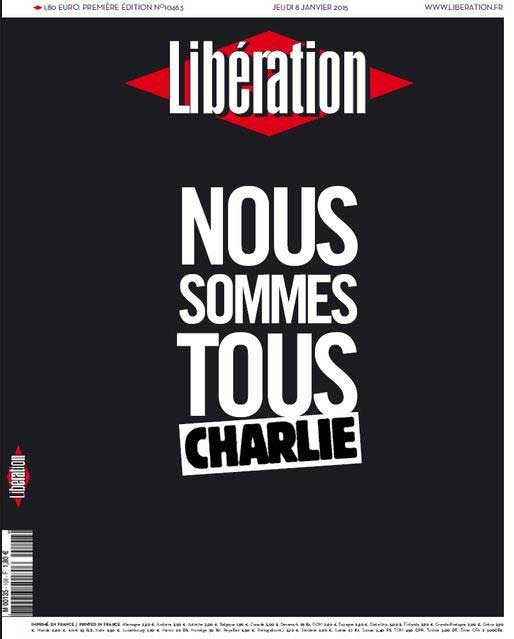

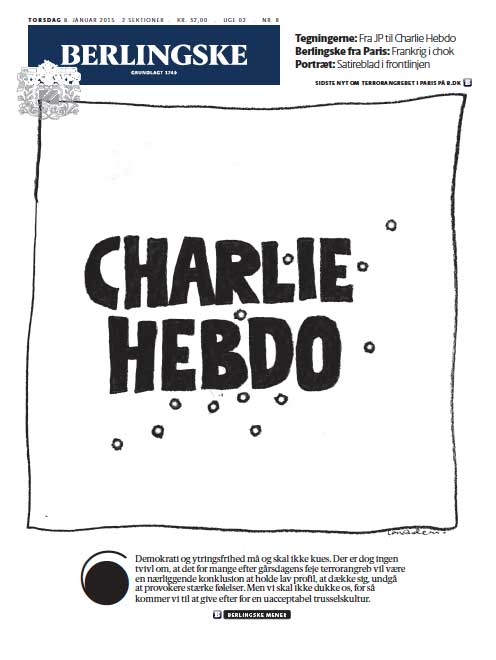

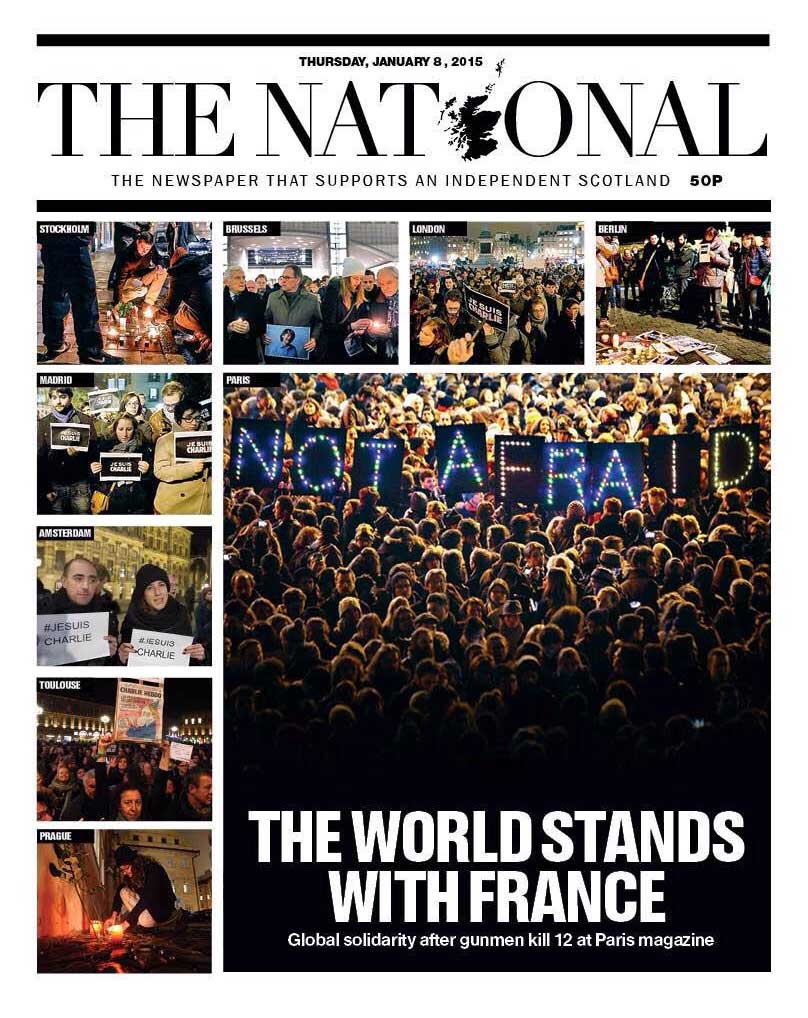

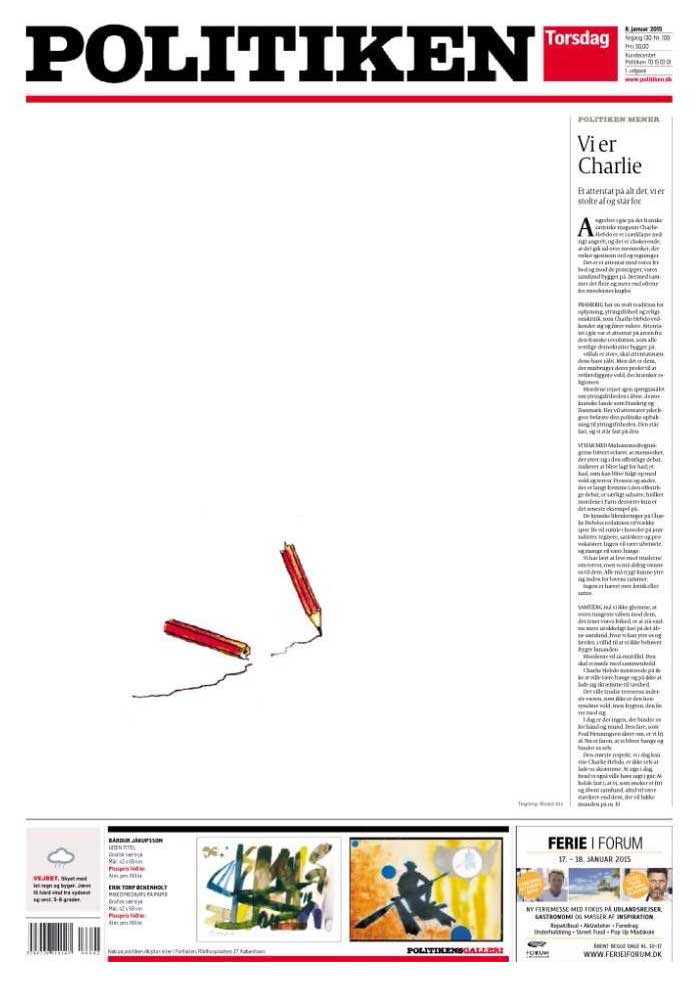

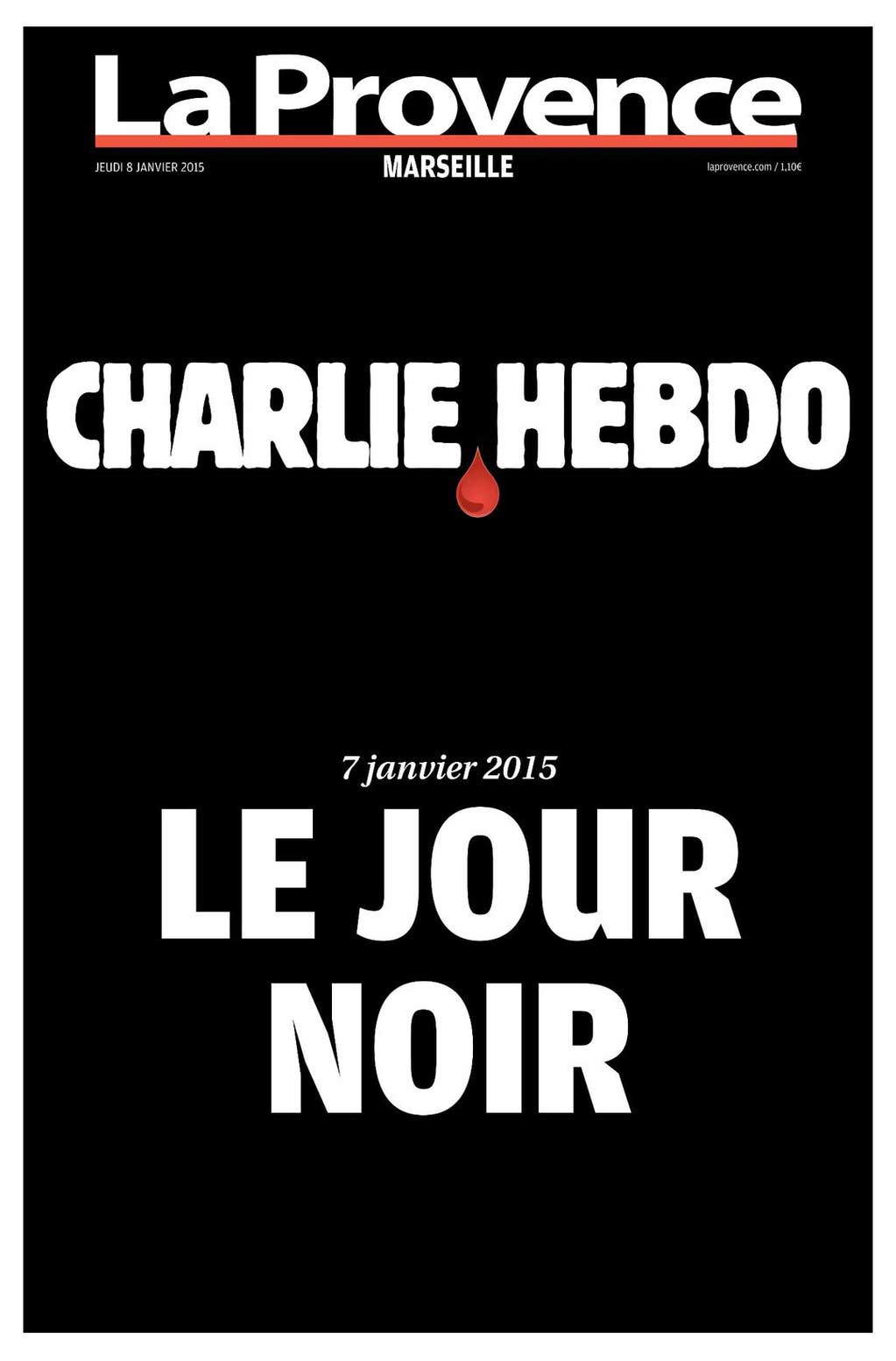

Front Pages React to Paris Terror Attack

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com