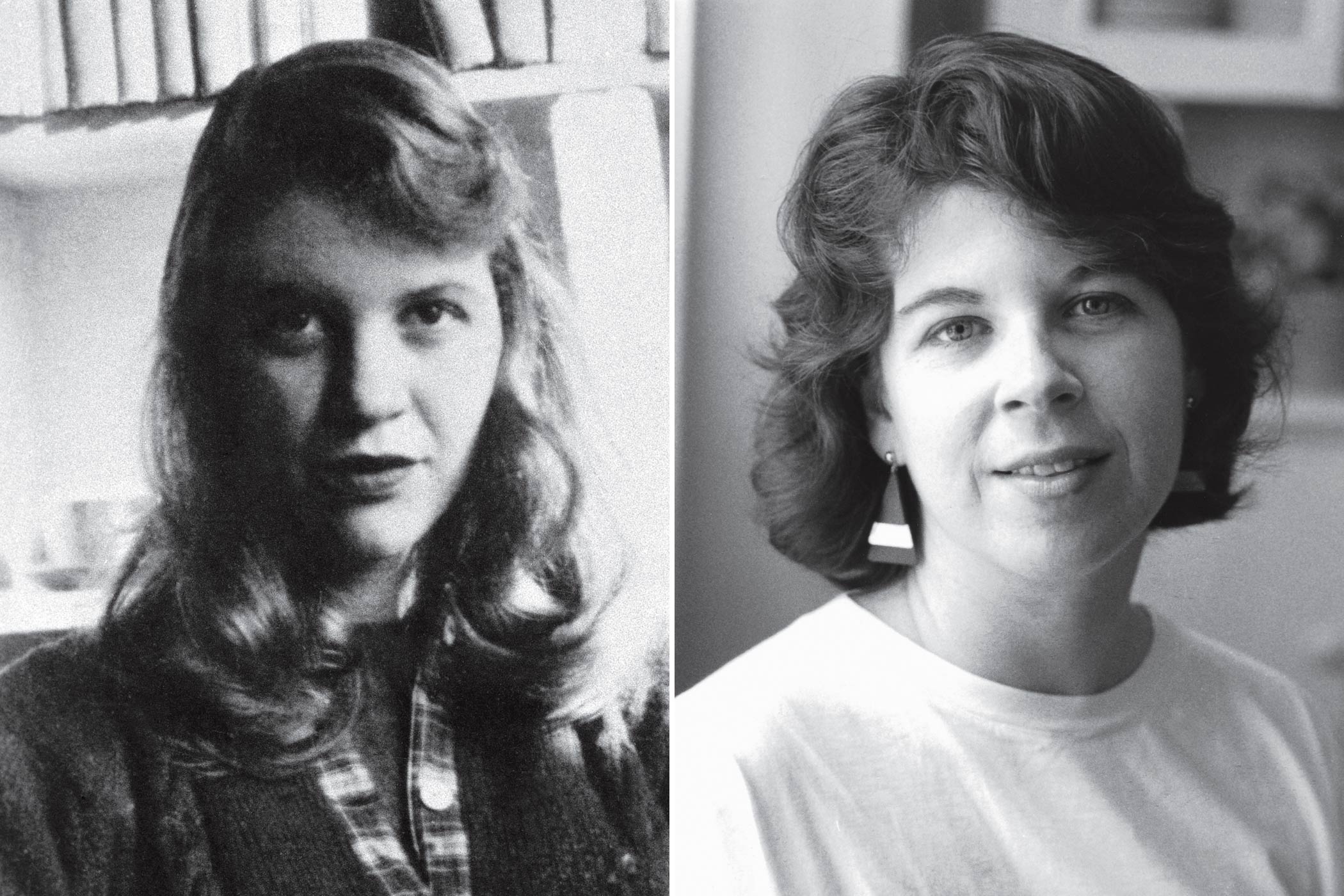

The first time I read Sylvia Plath’s autobiographical novel The Bell Jar, it was an emotional, chaotic experience. Her narrator has a nervous breakdown while a college student and attempts suicide, as Plath had. The story is so viscerally real and imaginable that I, then a teenager, was immersed. Plath, who recovered from her breakdown but committed suicide at age 30, left behind one powerful novel, many brilliant poems, a good deal of short fiction and voluminous journals. But it was in The Bell Jar that she used the detailed landscape of a novel to look bravely at her illness, and she compelled readers to look with her.

Flash-forward several decades. I had embarked upon writing a young-adult novel in which The Bell Jar plays a part. Belzhar (pronounced bel-jhar, a play on Plath’s title) is about a troubled girl, Jam Gallahue, who tragically loses her boyfriend and is sent to a therapeutic boarding school where she’s placed in a class that reads only one writer over the whole semester. This year, the teacher has decided they will read Plath.

Plath told the truth in The Bell Jar—I don’t mean only the autobiographical truth, though that was part of it—but also a larger truth about how emotional suffering can make people feel isolated under their own airless glass jars. Because of this truth, young readers like me were deeply affected and in some ways transformed. Had Plath been a famous suicide but not such a fine writer, her reputation would likely have fizzled out after her death. But she was uncommonly good, so she stuck. Teenagers read her when I was that age, and I sense that many teenagers still read her now.

And so, for research purposes, I read Plath again. But now, instead of responding only to the young narrator’s detachment and despair, as I had long ago, I also found myself, to my surprise, responding to the woman Sylvia Plath would never become. The writer who would never continue to mature with age. The mother who would never see her children off into the world. The person who wouldn’t have the chance to live a long life.

Younger me tended to take the short view, feeling everything along with the narrator as it happened and never thinking about that nebulous thing called the future. But now, as a middle-aged woman, I definitely took the long view. It occurs to me that not only readers but also writers often fall into the habit of taking either the short or the long view when they work. I’m a novelist whose fiction has mainly been for adults; my most recent adult book, The Interestings, lavishes a lot of time on its characters when they’re young. Then it keeps going, following them from age 15 all the way into their 50s—an age I can relate to well these days, as my children have left home, and I must remind myself to schedule my yearly mammogram.

But Belzhar, a novel about adolescents written for adolescent readers (although these days plenty of adults read YA too), takes place over the course of only one semester at boarding school. And while The Interestings is told from multiple points of view, Belzhar hews close to its narrator, letting her tell her story in a particularly close-grained way. Jam is someone who needs to talk, who is breathless and single-minded; making her a first-person narrator struck me as the best way to convey her voice, her neediness, her absolutely certain convictions about what had happened to her.

I couldn’t help but think, when writing this novel, of the two versions of me who had read The Bell Jar. Maybe there were two versions of me who should be writing Belzhar: one who was still close to the intensity of adolescence, for whom everything felt fresh and raw. That version, which still exists inside of me, took care of the parts in which I needed to drag up feelings buried in the overstuffed dresser drawer that is adolescence: What it’s like to make first-time emotional, romantic, even sexual decisions. What it’s like to manage the overwhelming new sensations and thoughts that invade you. What it’s like to feel rejected. What it’s like to realize that everyone is essentially on their own.

But then the older version of me had to put the whole thing into context, to remember that circumstances can change if you give them enough time, even if my narrator can’t know it. I wanted the older me to be somewhere in the mix of this YA book, though not to give Jam a goody-goody artificial voice of reason. Books aren’t morality plays; they don’t all need lessons. But given that Belzhar takes place in a special class at a special boarding school, it seemed appropriate that there would indeed be some kind of essential lesson conveyed.

And that’s the point at which Mrs. Q stepped in: Jam’s elderly teacher, a woman who knows quite a bit about how things can change. Without realizing it at first, I became part Jam and part Mrs. Q, shuttling between someone who takes the short view and someone who takes the long.

At book readings, audience members often ask how writers create characters. People want to know: Have writers actually experienced what their characters experienced? And if not, where do their ideas come from? My best, though incredibly vague, answer is that ideas come about through the long, slow process of living. Even if a character’s experiences aren’t your own, you are citizens of the same world, and you’ve had your experiences and witnessed other people’s too. While all that’s been going on, empathy has quietly been forming; it’s almost a chemical process.

And if you’re a writer, you’ve also been reading. A lot. And while Belzhar isn’t a ripoff or a retelling of The Bell Jar, it reflects on Plath’s novel and owes a debt to it. It’s not that you want to imitate the book you admire; you just want to do your version of what that writer did: you want to tell the truth, fiction-style.

There are quite a few of us former teenagers—women in the middle of their lives (and some men, for sure)—who have never forgotten what it felt like to read The Bell Jar for the first time. So what are we supposed to do with all that leftover feeling?

Me, I decided to write a book.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com