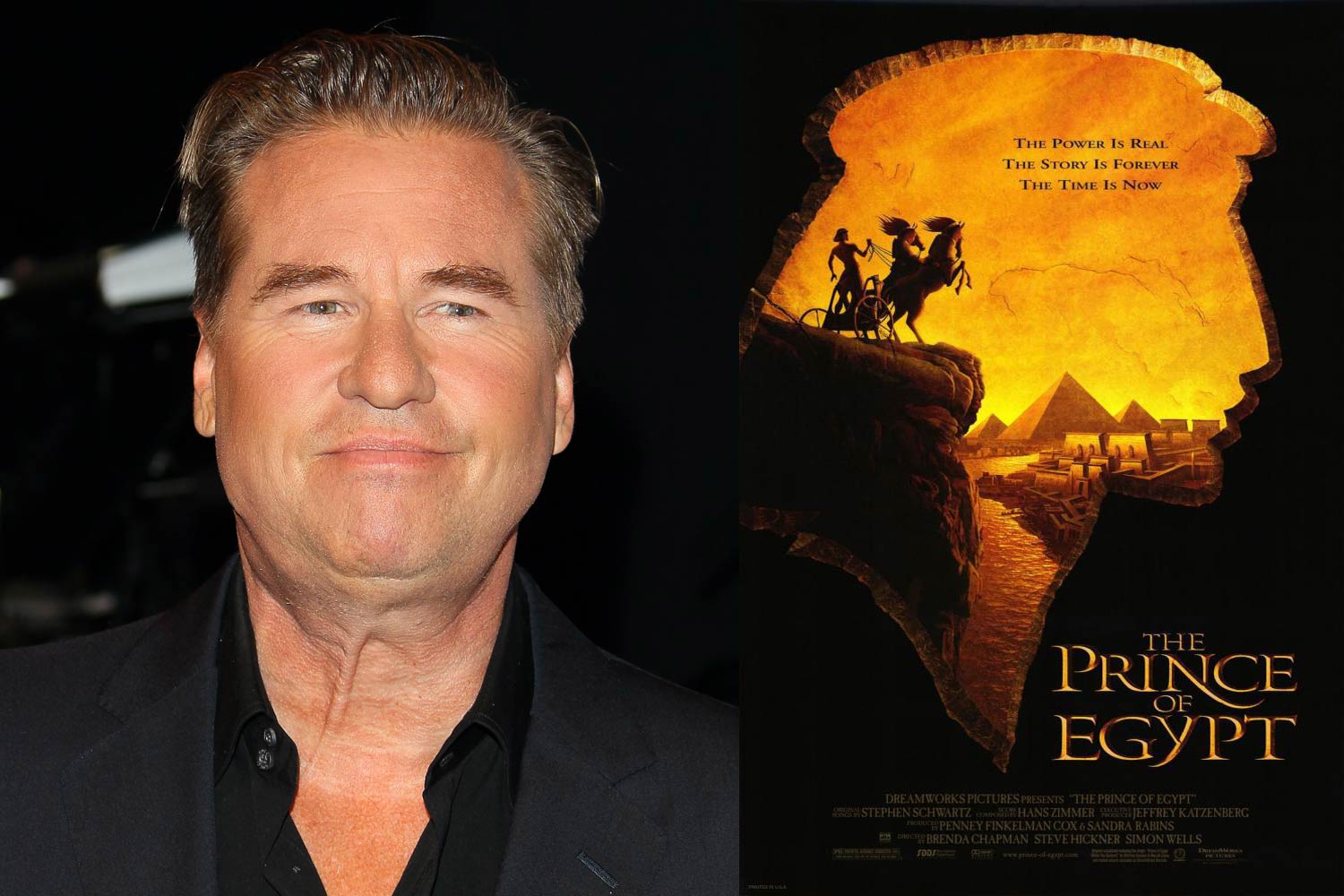

“And this is your famous Uncle Moses,” a Hebrew man says to a child in Ridley Scott’s Exodus: Gods and Kings. “He was once Prince of Egypt.” Renowned in movie history as in Bible history, Moses was indeed the star of the 1998 The Prince of Egypt, DreamWorks’ first animated feature, also known in the industry as The Zion King. In the 1980 comedy Wholly Moses! he was the upstart who swipes the Ten Commandments from Herschel, the would-be Hebrew hero played by Dudley Moore. Most memorably, Moses was Charlton Heston of the sturdy torso and stentorian voice in Cecil B. De Mille’s The Ten Commandments, released in 1956 and still, in terms of tickets sold, sixth among all-time box-office hits.

In Exodus: Gods and Kings, famous Uncle Moses is Christian Bale — also a looker, but employing an accent that wanders like the nomadic Jews from stately Brit-speak to American Urban-Tough. The movie got swathed in controversy during pre-production when certain groups complained that white actors had been cast as the Egyptians and Hebrews, anyway the Semites, of 1300 B.C. The director’s retort was brusque and businesslike. “I can’t mount a film of this budget [$130 million, plus about $70 million in tax rebates], and say that my lead actor is Mohammad so-and-so from such-and-such,” he told Variety. “I’m just not going to get it financed. So the question doesn’t even come up.” Somehow this assertion that no Islamic performer would be a significant lure — plus the casting of an actor named Christian as the Jewish prophet who leads his people out of 400 years of Egyptian slavery — didn’t calm the protesters.

Racial sensitivities aside, this Exodus is a stolid mess, bleakly laughable without being an entertaining hoot like De Mille’s camp classic. On the plus side there are some vividly depicted plagues — alligators turning the Nile red, locusts, hailstones, a toad torrent (the frog of war), boils for the soulless, helpless Egyptians — and, in the parting of the Red Sea, the snazziest “enormous wall of water” since… well, since Interstellar last month. On the minus side is everything else.

MORE: Exodus and the True History of Moses

Working from a script by Steven Zaillian (an Oscar-winner for Schindler’s List) and three lesser scribes, plus possibly a few uncredited Pharisees, Scott presents Moses as a wise warrior, hunky dude and favorite of the Pharaoh Seti (John Turturro). Seti’s son Ramses (Joel Edgerton) is an envious coward who boasts of achieving the military triumphs actually earned by Moses. In Ramses we have the standard friend-rival figure who hounds the lower-born hero, as seen in Biblical and Roman movie epics from The Ten Commandments and Ben-Hur (Heston and Stephen Boyd) to Scott’s own Gladiator, where Russell Crowe is the solider soldier and Joaquin Phoenix the Emperor’s sicko son.

Scott’s royal Egyptians — Seti, Ramses and the Queen Mum Tuya (Sigourney Weaver) — are, in a way, colored. They’re golden, as if they’d rolled around in the largesse of Smaug’s cave and emerged as six-foot versions of the Oscar statuettes this movie will not be receiving. (According to Edgerton, he was also obliged to wear “gold underpants.”) A few actors from sub-Saharan Africa play minor roles, but only as slaves — another nettle for prickly reviewers. At least Wholly Moses!, a Life of Brian-esque parody of the Bible, had the racial grace to cast Richard Pryor at the Pharaoh.

Buff and buttery, with a sideline in snake-wrestling, Ramses sports heavier makeup than a Real Housewife of Memphis, or Lipsinka. He and his family swan around the palace, rolling their blue eyes and signaling almost as much homoeroticism as you’d find in a Seth Rogen bromance. Ben Mendelsohn, as Viceroy Hegep, is a fruit salad of gay mannerisms and Jewish jibes. (He calls the Israelites “a conniving, combative people,” adding, “And I thought you people were supposed to be such good storytellers.”) The one performer having ostensible fun with his role, Mendelsohn may also be the only one who watched the De Mille film and took his cue from Yul Brynner’s preening Pharaoh.

Ten Actors Who Have Played God (In Film)

All this might be news to Scott, whose cinematic gifts are for marshaling strong images around dead-serious stories and not for sly satire with a feygele touch. Perhaps he means to portray the decadence of the Egyptian hierarchy, or of any family long in power. But most directors would try to give the imperial bad guys a little majesty, so the hero’s victory over them might have something to savor. The royals here are just fops who, with or without Moses, might have died out on their own, of inbreeding or ennui.

Stinting on the Moses backstory — of being set afloat by his mother for discovery by Pharaoh’s daughter — Scott first presents him as an outsider adopted by the Egyptian court. In an ancient variation on the famous Saturday Night Live “Jew, Not a Jew” sketch, Moses is an adult before becoming fully aware of his Hebrew heritage. When Ramses learns that his military better is a foreign slave, he banishes Moses. In the wild, the outcast builds a family, meets his God and fulfills his destiny.

MORE: How Ridley Scott’s Exodus Strays From the Bible

In another case of foot-in-mouth disease, Scott called religion “the biggest source of evil” — maybe not the most judicious way to promote an expensive movie that relies on the support of fundamentalist Christian audiences. He promised that his skepticism would make him the ideal fellow to tell a Bible story, because he’d first have to convince himself of its dramatic plausibility. That approach worked for Darren Aronofsky, the director of Noah earlier this year; he turned that Genesis tale into a climate-change parable of spiraling ambition and hallucinogenic wonder.

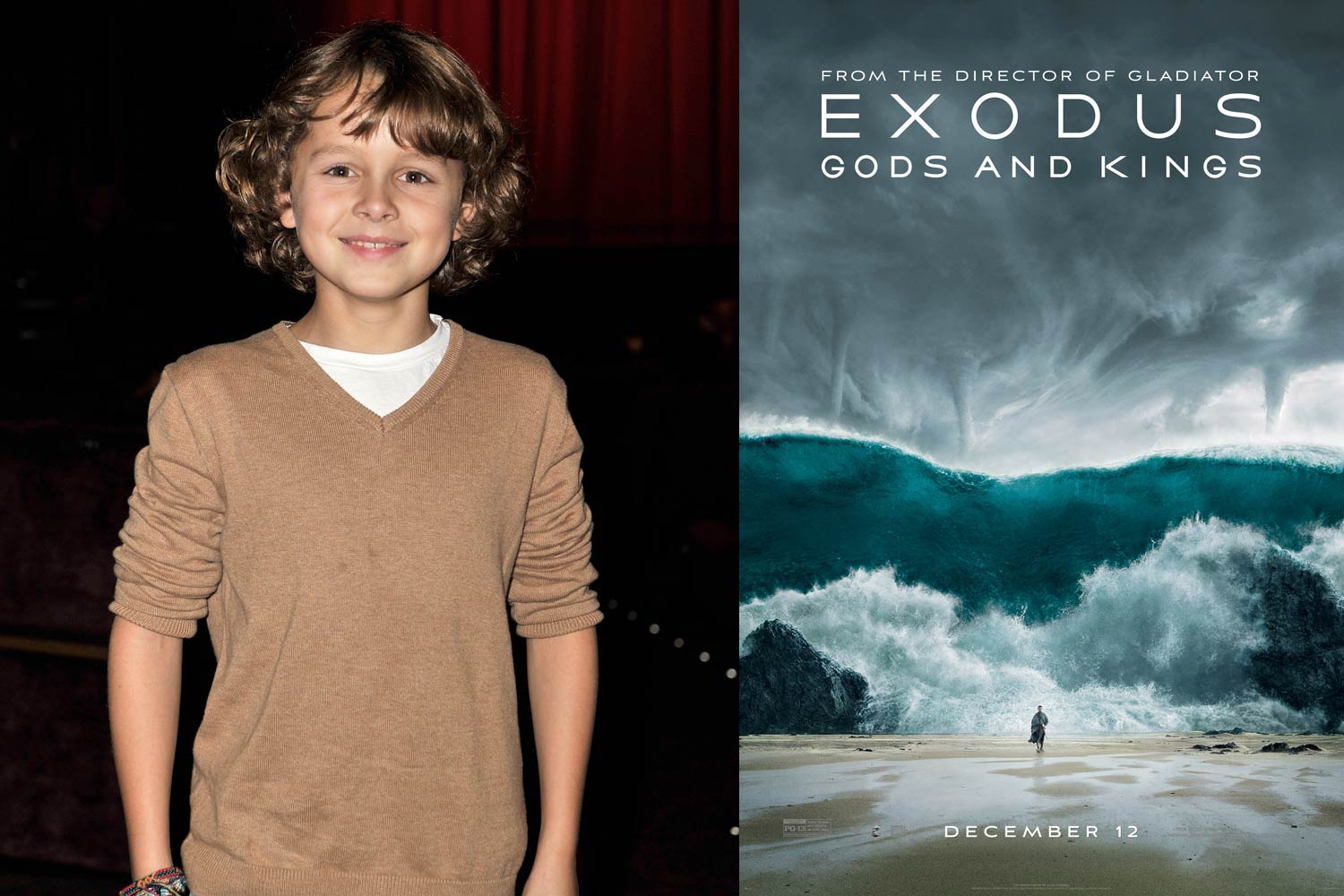

Not so for Scott, whose only risky choice was to make the Old Testament deity an 11-year-old boy (Isaac Andrews) with a balky disposition. He’s not genteel but a Gentile — a boy-God with a Goy bod — whose plan to free the Jews is to rain plagues on the Egyptians. Moses isn’t convinced. “From an economic standpoint, what you’re saying is problematic, to say the least,” he says, in clunkily verbose contrast to the God-child’s Pinteresque conciseness. When Moses asks, “Who are you?”, He replies simply, “I am,” which is arguably an improvement on the King James translation (“I am that I am”) or the Basic English Bible’s “I am what I am.” Popeye said that too.

He Who Is sets about tormenting the Jews’ tormentors, capped with the slaughter of every Egyptian first-born male — the event that Passover celebrates — while famous Uncle Moses leads his people through the CGI miracle of a parted Red Sea. The sequence is technologically impressive but, like everything else in Exodus: Gods and Kings, it lacks passion. Most secular audiences don’t care whether a movie like this is canonically faithful or a libel on the Bible. It also shouldn’t matter whether the director of such a film is Jewish, Christian or agnostic. But he has to believe in something, if only in his hero’s commitment to a quest or the thrill of Almighty spectacle. Otherwise, it’s not an epic; it’s just a waste of time and effort.

The movie’s sole genuine emotion comes at the very end, with the director’s dedication “For my brother, Tony Scott.” The younger Tony, who committed suicide in 2012, was known for highly sexualized, very American modern melodramas such as Top Gun and True Romance. Ridley usually took the loftier road of period epics like The Duellists, Kingdom of Heaven and of course Gladiator, which won the Oscar for Best Picture in 2001. “Nobody does toga movies like my brother,” Tony said.

Tony Scott didn’t live long enough to see Ridley’s kaftan movie, or to ask him the question that hangs over the full 150 mins. of this stillborn epic: If you don’t have something new to say or show, why make it?

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com