Scarlett O’Hara famously vowed she would lie, steal, cheat or kill to survive. And just like its heroine, Gone with the Wind has shown remarkable resilience. Celebrating its 75th anniversary this year, the film remains a fixture in popular culture. Its iconic status is more secure than ever, thanks to television, DVDs, parodies and revivals that roll around as regularly as national holidays. Just as amazingly, Margaret Mitchell’s 1,037-page novel has been in print since it became a best-seller in 1936, its life extended by a prequel, a sequel—and, of course, the movie.

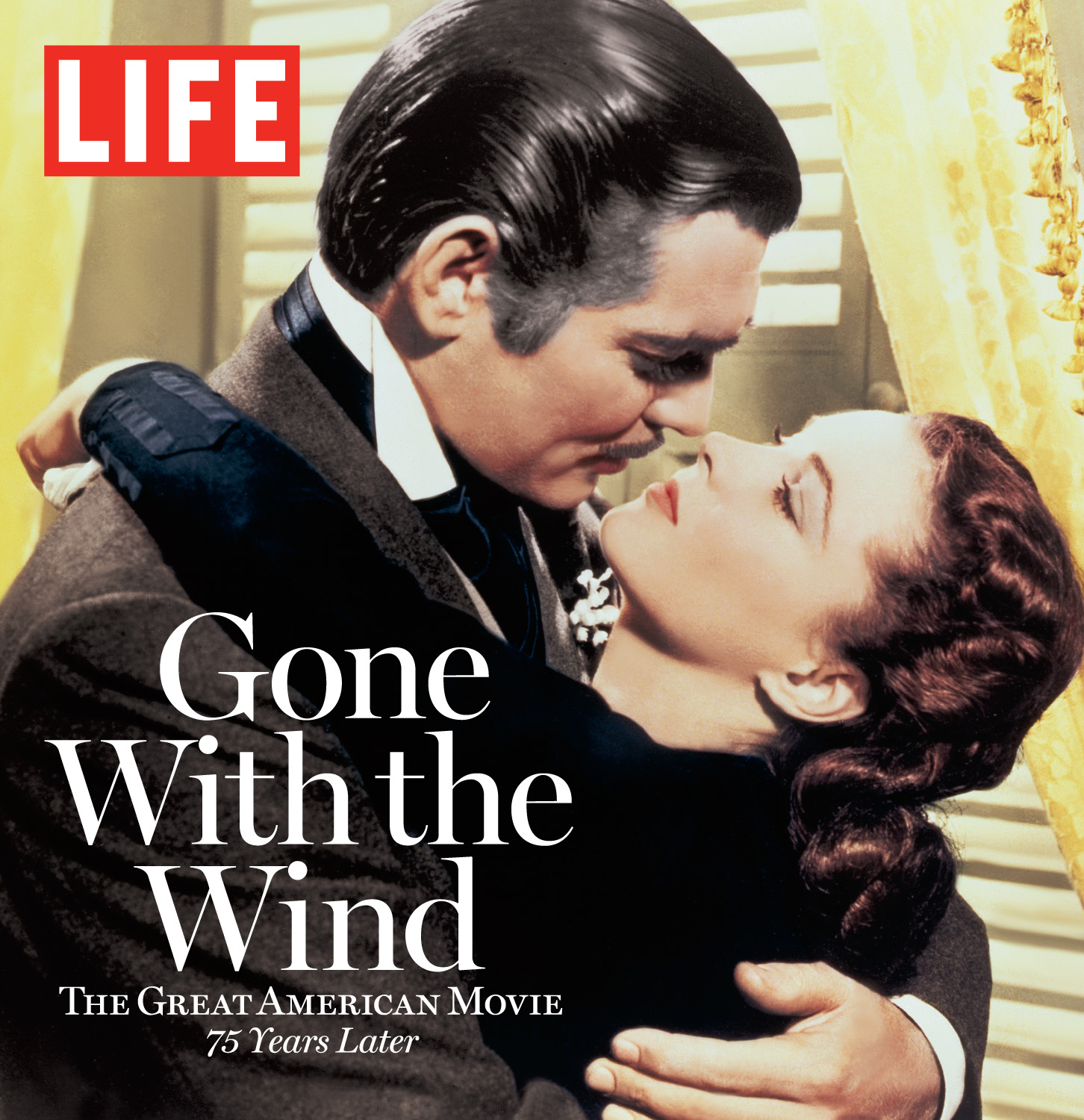

The story of a small corner of the South in the 19th century, a war movie with no battle scenes, revolving around a heroine of questionable morals, has proved uncannily adept at crossing barriers of geography and time. The poster of Scarlett and Rhett posed against the flaming sky is as instantly recognizable in China or Ethiopia or France as the American flag. The movie is still the biggest blockbuster in history with ticket prices adjusted for inflation. And if it doesn’t have quite the must-see thrill it once did, if many of its transgressions appear fairly innocuous today, others are as fresh and controversial as they were in 1939.

Politically incorrect and racially retrograde, GWTW has offended so many sensibilities that the overture should be preceded by a trigger alert: Beware! This is history written by the losers. The Yankees are irredeemable villains; the slaves too happy in their subjugation to yearn for freedom. The marital rape, in which Rhett forces himself on Scarlett and—horrors!—she enjoys it, can still raise the blood pressure of feminists. But the allure of Gone with the Wind is more powerful, fed by fantasies that run roughshod over ideology.

I came to it as a Southern teenager in the ’50s, when the book was a sort of underground bible. We consumed it under covers with a flashlight, much as Margaret Mitchell read the romance novels her bluestocking mother deplored. The movie, ideally cast, preserved all the disreputable qualities of its heroine, the delicious ambiguities of good boy and bad boy in her two lovers. As with the book, we embraced the movie in a state of critical and political innocence. Max Steiner’s sweeping score is nothing if not relentless, yet who can hear the first few chords of Tara’s theme without experiencing a frisson?

There is a reason so many studios turned the property down. The book was too long, its legion of admirers too passionate. They would detect any alteration, would brook no compromise. And who could play the crucial and near-impossible role of Scarlett? A known movie star would bring too much baggage, an unknown wouldn’t have the chops. The budget would be prohibitive. Only producer David O. Selznick had both the ego and cultural pretensions to even attempt it, and he passed many an insomniac, pill-fueled night as the $4.25 million production went through five directors, 15 screenwriters, firings and rewritings, not to mention finding the leading lady only after shooting had begun. In the end, what should have been one of the great disasters was a triumph, not just a blockbuster and winner of 10 Academy Awards, but a showcase of a kind of filmmaking that we would seldom see again. Yet the irony can’t have escaped spectators: The New World’s most democratic medium had given us the portrait of an aristocratic past whose seductiveness depended on the denial of unpleasant truths.

The scapegrace daughter of a high-minded suffragette, Margaret “Peggy” Mitchell was a tomboy truant, then a flapper who acted up at parties while her mother marched for the vote and attended to the sick. From this dividedness comes Scarlett, an unresolved amalgam of the high-spirited party girl, thumbing her nose at proprieties, and the lost girl, longing for the love of a disapproving mother.

Officially she would have nothing to do with Selznick’s film, thus providing herself with deniability should her fellow Atlantans be outraged by the movie’s vulgarities. In her letters, she took a line of baffled innocence. The book had “precious little obscenity in it,” she wrote disingenuously to a correspondent, “no adultery and not a single degenerate, and I couldn’t imagine a publisher being silly enough to buy it.”

Macmillan bought it, of course. With very little effort on the publisher’s part, Gone with the Wind sold 1 million copies in the first six months, then (with a great deal of effort on the part of Selznick et al.) it became an Oscar-winning movie, all with its degeneracy intact. I’m thinking of such no-no’s as a house of prostitution patronized by Rhett Butler and other Atlanta notables; the marital rape; a near rape in Shantytown (Scarlett is attacked by a black man in the book, saved by one—Big Sam—in the movie); adultery of the soul if not of the body between Scarlett and Ashley; and a farewell punctured by a four-letter word not allowed on the heavily censored movie screens of the time. The offenses against gentility include a harrowing childbirth and, against virtue and Hollywood conventions, a heroine of unprecedented selfishness who lies and cheats her way through Reconstruction, stealing her sister’s man in the process. Mitchell’s way of rationalizing her she-devil protagonist was to maintain that Melanie was the heroine, not Scarlett. Or was meant to be.

But we teenagers knew forbidden fruit when we tasted it. In the uptight, prefeminist ’50s Scarlett was a slap in the face to all the rules of white-gloved ladylike behavior in which we were steeped, a beacon (however tarnished) of female wiliness and defiance. She looked marriage and adulthood square in the face—a life on the sidelines, matronly chaperones in dowdy clothes—and would have none of it. Proudly adolescent, a rebuke to grown-up hypocrisy and conformity, she’s the opening salvo in the teenage revolution, pioneer of a new demographic that would become official with rebel James Dean.

Naturally, the first American readers and audiences saw GWTW as a fable of the Depression, when men were laid off and women were compelled to find ways to survive. Later it would inevitably echo the reality of the Second World War, with men fighting abroad and women going to work for the first time. Perhaps more surprising is the way the movie has enraptured hearts and minds around the world. From postwar France, left-wing cine clubs in Greece and prisons in Ethiopia, there have come stories of people who are by no means sympathetic to slave-owning Dixie, but who nevertheless identify with the South and see it as a mirror of their own travails. Maybe it’s because GWTW is not about bravery on the battlefield but the courage of resistance, of holding it together, of coming through in the clutch—in other words, gumption, Margaret Mitchell’s favorite word. The Darwinian struggle is between, as Ashley says, “people who have brains and courage . . . and the ones who haven’t.”

This confusion of good and evil, of winners and losers, is embedded in the very marrow of Gone with the Wind, as it is in the idealized vision of the South so long cherished by the former Confederacy. Margaret Mitchell spent hours as a child on her grandmother’s porch, listening to relatives tell war stories. She claimed not to have realized until she was 10 years old that the South had lost the war. And so it is that in the face of unacceptable defeat, she gives spiritual victory to her characters. If Scarlett is the motor, Yankee-like in her drive, the impractical, ungreedy Ashley embodies the South’s moral ascendancy. Audiences, as well as characters in the movie, tend to cut Scarlett a surprising amount of slack, rationalize her selfishness as necessary (and very American) expediency. GWTW is full of such questionable fudgings and South-justifying sentimentalities, and its reception, never unmixed, has been plagued by stories that haunt us. Butterfly McQueen could never escape the role, or voice, of Prissy. And though Hattie McDaniel would end up winning the Oscar for playing Mammy, she couldn’t attend the premiere in segregated Atlanta.

Still, it’s important to give Mitchell and Selznick the benefit of context—different time, different rules; and they were more progressive than many around them. As a Jewish man, Selznick understood persecution and didn’t want to go to his grave with the racist legacy of D.W. Griffith. He listened to advisers and blacks on the set, and dropped the word n-gger (used in the book by blacks in reference to one another). Mitchell was a product of the Jim Crow South, but wound up funding education for blacks at considerable risk to herself.

The film, with all its complications and controversies, with all its success, proved as much a burden for its authors as a joy. Margaret Mitchell was overwhelmed by attention and ailments and died at age 48. Selznick, too, suffered from the stress, and Vivien Leigh, the third obsessive of the trio, gave so much of her unstable self to the incandescent Scarlett that she displayed symptoms of burnout the rest of her life.

You are about to embark on a fascinating journey into the heart of an American epic—some would say the American epic. As you read the juicy stories about the making of the movie and the making of Mitchell, you may find, as I did, that the film remains a testament to the manic dedication of Selznick, Mitchell and Leigh . . . and to a fourth partner, the viewers, who have made the film—intensely—their own.

LIFE’s book Gone With the Wind: The Great American Movie 75 Years Later is available here.

See photos from the Gone With the Wind set here, and from the making of the movie here

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com