In 1987, photographer Michel du Cille immersed himself in the lives of Miami crack addicts inside a dangerous apartment complex known to its residents as the Graveyard. Working alongside the tough and talented young reporter Lynne Duke, du Cille produced a definitive document of the social and human tragedy that was the crack epidemic. Michel’s work for the Miami Herald’s Tropic magazine won the Pulitzer Prize—one of three Pulitzers honoring this important and influential photojournalist.

His editor on the piece, Gene Weingarten, was struck by the fact that Michel went to work without a camera. For weeks, he haunted the Graveyard with empty hands, learning to see human beings before making them his subjects. Knowing them meant revealing himself. “I want them to get to know me as a person,” Michel said. “First comes trust, then the work.”

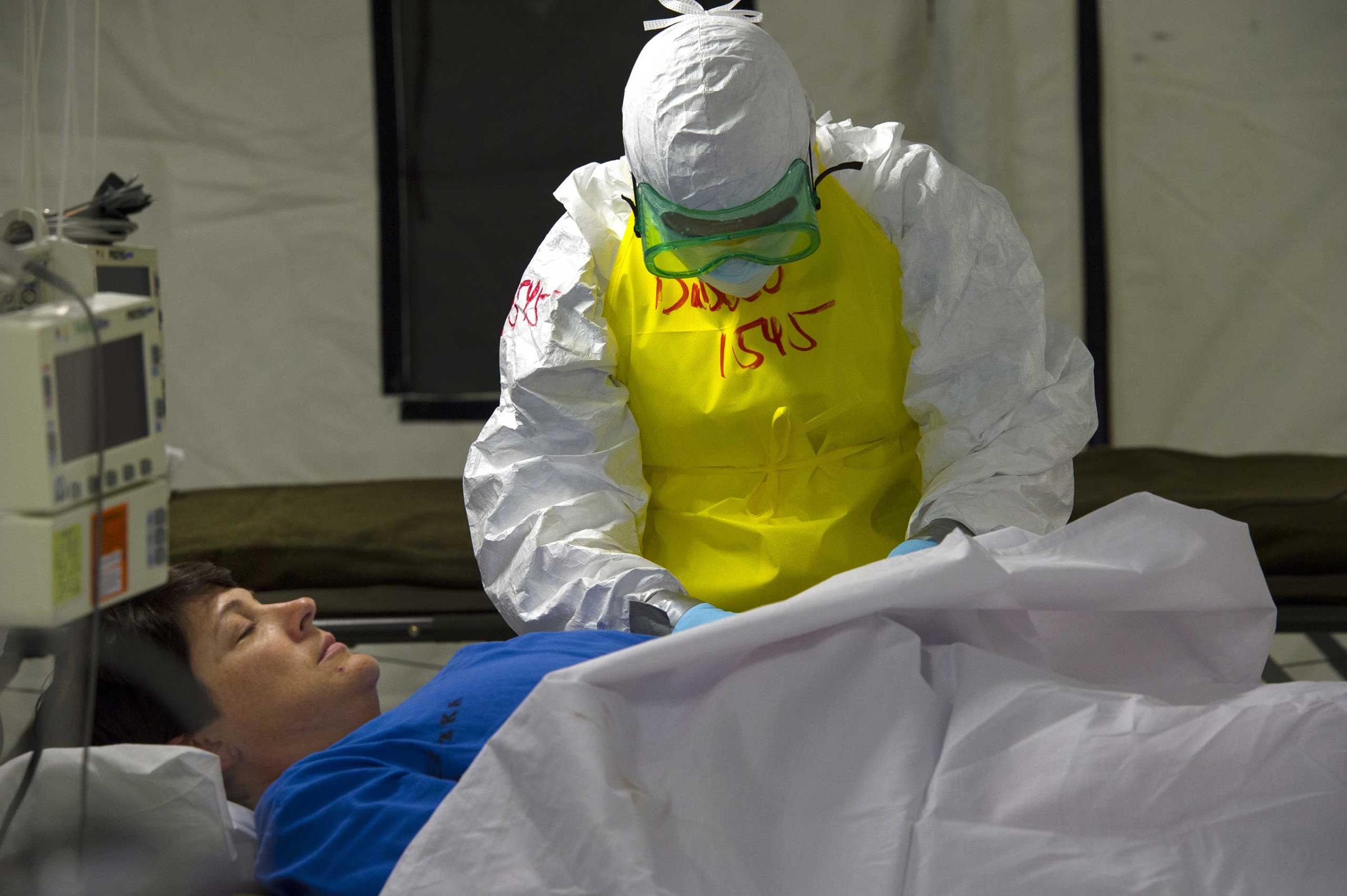

Du Cille died this week as he lived, taking the long, honest path. He despised shortcuts. At 58, he was hiking miles of remote West African trail in pursuit of the Ebola epidemic for the Washington Post. Evidently, he suffered a heart attack.

A great news photograph—and Michel du Cille made many of them—reveals its subject in a way that writing can never match. What may be less obvious is that a great photograph also reveals the photographer. Writers can sketch scenes based on interviews; spin tales from notes and transcripts. The photographer must be present at the critical moment; there can be no substitute. This almost always means hours, days and weeks of preparation before the moment comes.

I was honored to work with Michel for many years at the Herald and the Post, and I remember him as a journalist of unrelenting integrity. He spoke in a soft voice with the faintest seasoning of his native Jamaica, and his was the still, soft voice of conscience. He demanded the best from himself and expected nothing less from the rest of us.

Together with the brilliant and hilarious editor Joe Elbert, du Cille built the Post’s photography department into one of the most distinguished in newspaper history. They were yin and yang, boisterous Joe and quiet Michel, but they prided themselves on their shared commitment to utter candor. They critiqued portfolios like Marine drill instructors, breaking the photographers down before rebuilding them in stronger form.

When Michel stepped down from senior newsroom management to resume life as “a shooter,” he immediately reminded us that he could walk the walk. His deeply humane work documenting the neglect of wounded soldiers at Walter Reed Army Medical Center perfectly complemented the wrenching investigation by writers Anne Hull and Dana Priest, and earned the Pulitzer gold medal in 2008.

That he eagerly volunteered to go into combat in Afghanistan after cancer treatment and a pair of knee replacements tells you a lot of what you need to know about Michelangelo Everard du Cille. That he wrote with searing openness about the challenge of honoring the dignity of Ebola patients while documenting their wretched suffering tells you the rest. He worked in images, but his passion was reality. No picture could be worthy unless it was honest.

Chip Somodevilla of Getty Images says that he leans daily on a lesson he learned from du Cille. “He said to always look at the subject—the action—from all angles. He said to literally walk a circle around your subject to see it from a different angle, and wait for the surprises to come. That is very sound and sage advice from a man who never stopped telling stories that surprised, touched and moved us all.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com