Last week, Sen. Jeff Merkley announced that he will be introducing a comprehensive LGBT non-discrimination bill in the spring, which means, among other things, that a lot of lawmakers and media outlets are going to be making decisions about how they talk about LGBT people.

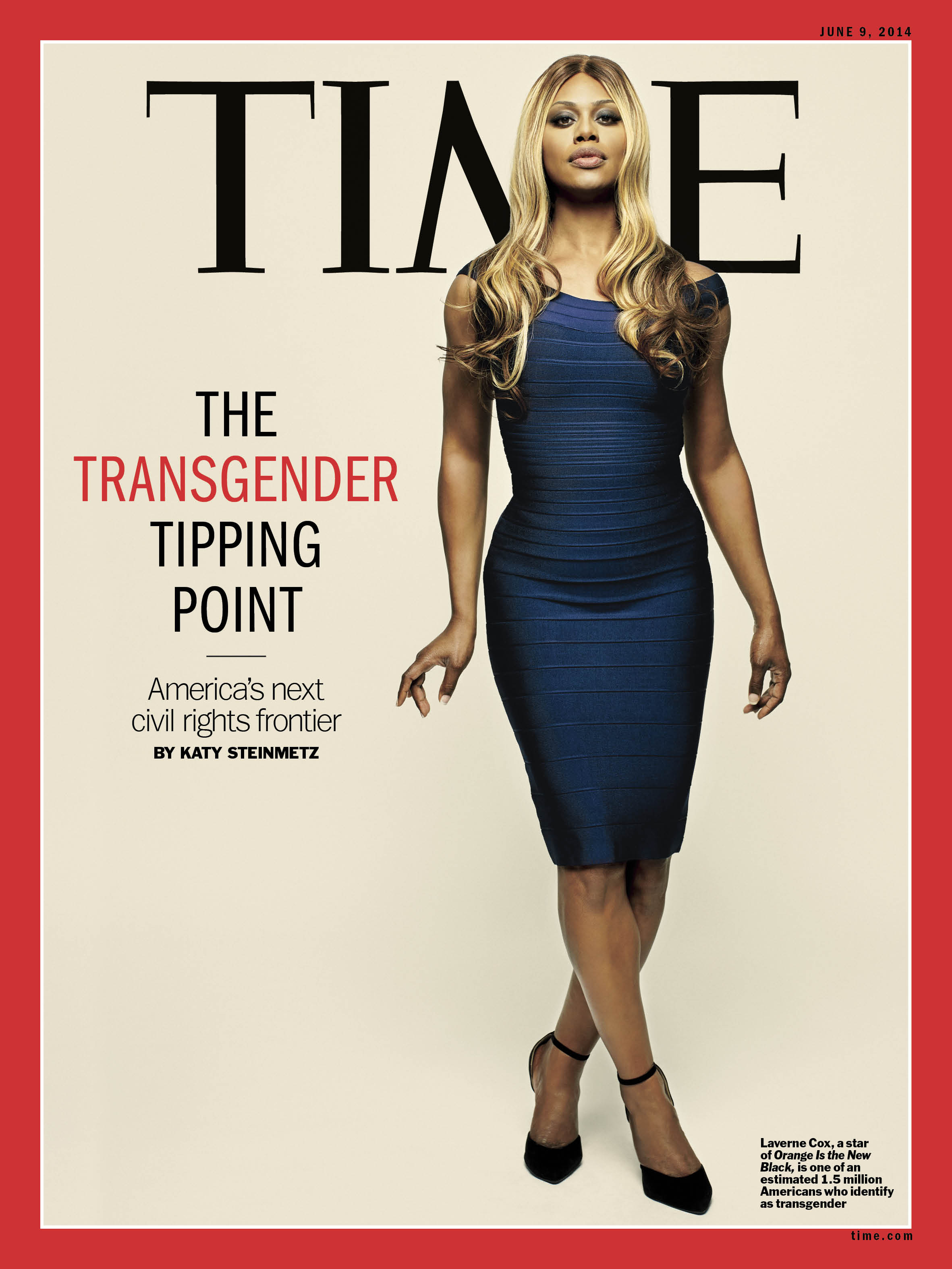

Reporting for TIME on transgender issues (particularly for what became the cover story “The Transgender Tipping Point”), there was one maxim that pretty much every person I interviewed seemed to agree on: there is no single story about being transgender that sums it all up, much like there’s no one story about being Hispanic or blonde or short or straight that sums that experience up. But I also came to learn that there are some good rules of thumb to follow when it comes to language.

For instance, if you meet a trans person—someone who identifies with a gender other than the sex they were assigned at birth—it’s generally a good idea to ask which pronouns (he or she, him or her) they prefer and to use whatever that is. If you meet a trans person, you should not ask about the particulars of their body, much as you would likely prefer strangers not to inquire about yours. And if you meet a transgender person, you should not refer to them as “a transgender” or “transgendered.”

Referring to someone as “a transgender” can sound about as odd as saying, “Look, a gay!” It turns a descriptive adjective into a defining noun and can make the subject sound distant and foreign, like they’re something else first and a person second. This guidance is part of GLAAD’s media reference guide, under the heading “Terms to Avoid”: “Do not say, ‘Tony is a transgender,’ or ‘The parade included many transgenders.’ Instead say, ‘Tony is a transgender man,’ or ‘The parade included many transgender people.’” These key language nuances haven’t been consistently adopted by the media. For example, on Dec. 15, the Associated Press listed this story in among their “10 Things to Know For Today:”

4. PHILIPPINE AUTHORITIES CHARGE US MARINE WITH MURDER

Prosecutor says the 19-year-old American is accused of killing a transgender in a hotel room. (The story has since been updated to say a “transgender woman.”)

This is something TIME has done in the past, too.

Of course it’s hard to find a word in identity politics that goes undebated, that is universally panned or lauded as just right. Julia Serano, author of Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity, says that older transgender people might prefer and use transgendered when speaking about themselves; in the 90s she recalls that term being de rigueur among trans activists.

But the language people use to refer to themselves, particularly minority groups, changes. Today some people prefer the abbreviated trans or trans*, and transgendered has largely fallen out of favor (though some media outlets are still using it). When I recently asked San Francisco-based attorney Christina DiEdoardo, a transgender woman, how many out of 10 trans people she knows would say they dislike the word transgendered, she quickly answered: “11.”

“The consensus now seems to be that transgender is better stylistically and grammatically,” DiEdoardo says. “In the same sense, I’m an Italian-American, not an Italianed-American.” The most common objection to the word, says Serano, is that the “ed” makes it sound like “something has been done to us,” as if they weren’t the same person all along. DiEdoardo illustrates this point, hilariously, with a faux voiceover: “One day John Jones was leading a normal, middle-class American life when suddenly he was zapped with a transgender ray!”

Moving away from the “ed”—which sounds like a past-tense, completed verb that marks a distinct time before and a time after— helps move away from some common misconceptions about what it means to be transgender.

One is that being transgender might be a choice that involves a person simply deciding to be that way or a result of something that happened to them, like sexual abuse. The majority of trans people I’ve spoken to have said they knew they had feelings of identifying as a boy (when assigned female) or girl (when assigned male) as far back as they can remember—even if they didn’t have the vocabulary or understanding to articulate what was going on—and even if they tried to change or stifle those feelings for half their lives. Imagine how it would sound if one described people as “gayed” or “femaled,” as if there was a point when that wasn’t the case.

Another misconception is that the defining part of being transgender is having surgery, as if a trans person isn’t really trans until they’ve gone under the knife and come out the other side fully “transgendered.”

“There’s a tendency in American culture for entertainment and news outlets to focus on surgery, surgery, surgery,” Mara Keisling, executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality, told TIME in a previous interview. But, she says, while surgery is very important for some trans people, others have no desire to have surgery; they might not have surgery for medical reasons, religious beliefs, financial constraints and so on. There’s an “authenticity issue that trans people face,” says Elizabeth Reis, a professor of women’s and gender studies at the University of Oregon. “People are so focused on whether or not they’ve had surgery, as if that’s the pinnacle of authenticity. Even if they haven’t had it or if they haven’t had it yet or they’re never planning on having it, they still have these feelings about their gender.” Avoiding the ed isn’t going to solve that authenticity issue, but it doesn’t hurt.

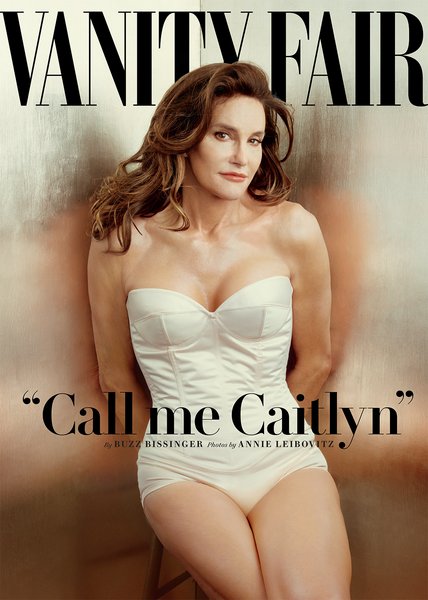

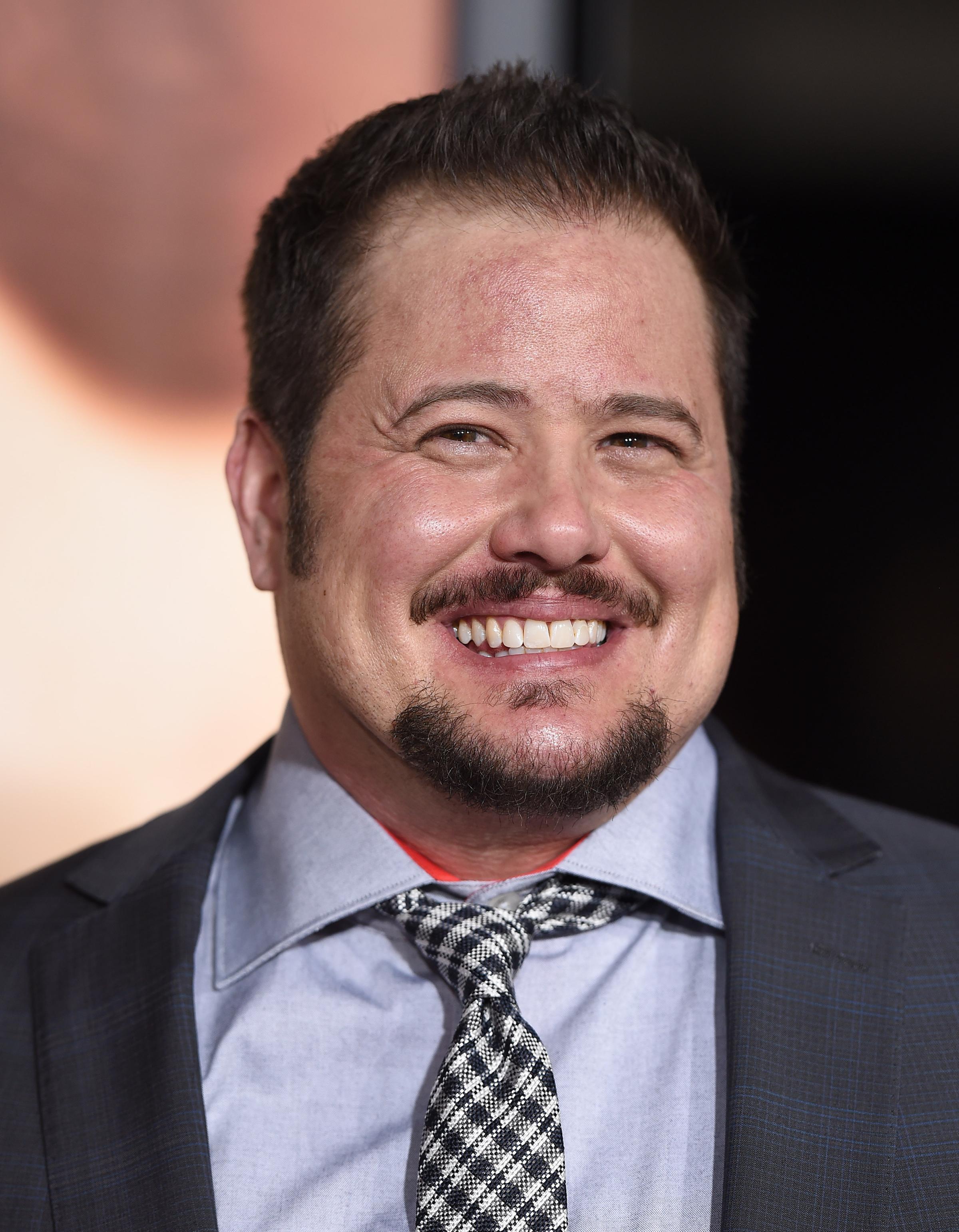

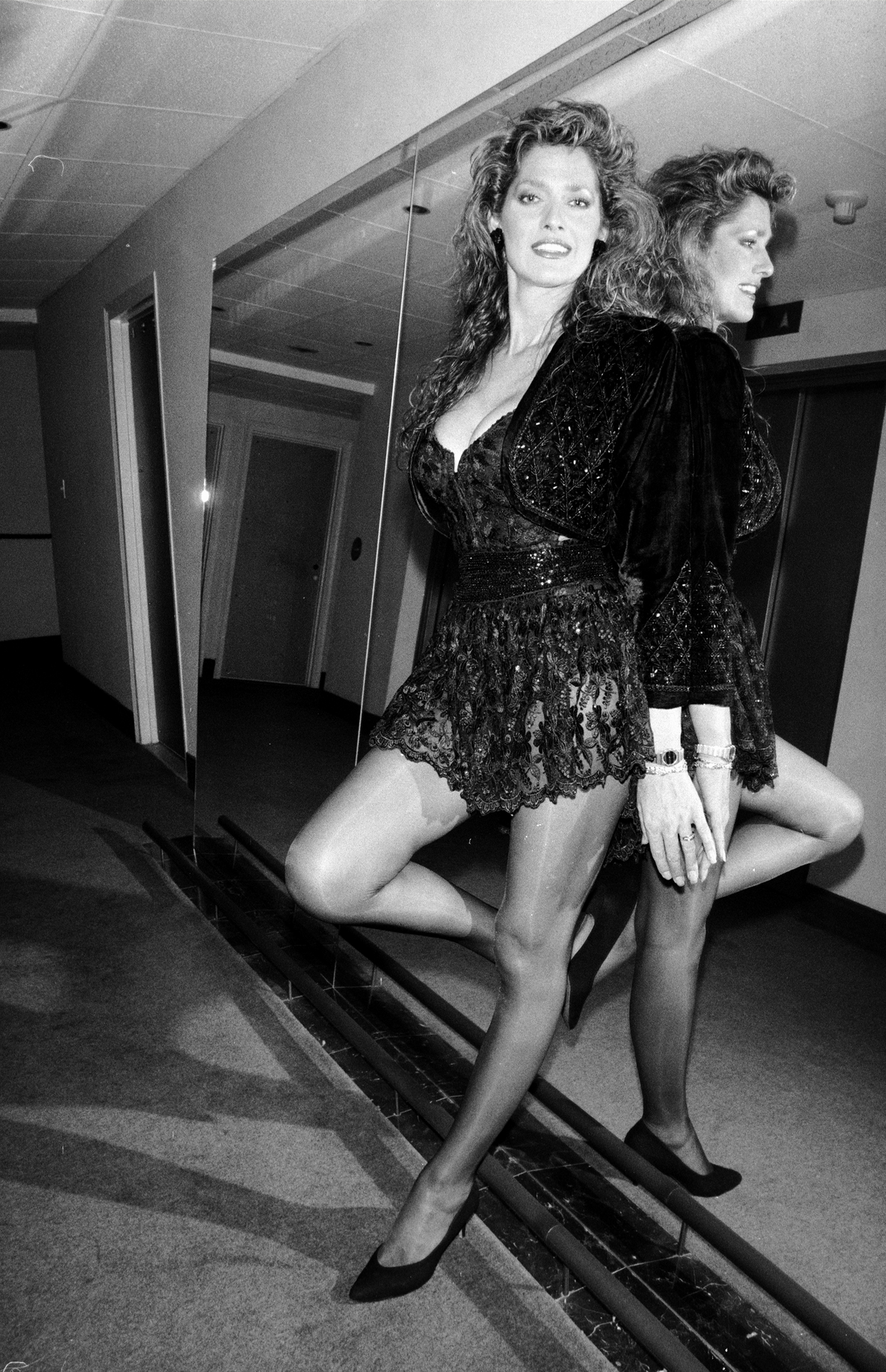

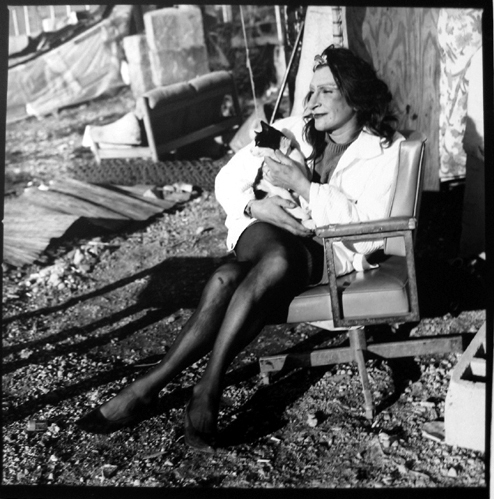

Photos: 25 Transgender People Who Influenced American Culture

However, Keisling also says that focusing on whether the “ed” is tacked on the end of transgender can be a distraction. She believes it’s more important for everyone to be having a conversation about LGBT civil rights issues than to wag fingers at people over terminology. “I don’t ever want to say that communities or cultures can’t have language variations,” she says. “Language is very important and what people want to be called is very important. But we have to have a common language that we can bring people into. We have to have language that they can grasp.” And, she says, just as transgendered has become unpalatable, there’s no telling what will be preferred down the line.

Still, “for now,” Keisling says, “I would use the word transgender. Particularly if you are outside of the family, that’s going to be okay.” (If you have more questions about terminology, the GLAAD media guide is a great place to start.)

Katy Steinmetz is a TIME correspondent based in San Francisco. In addition to writing features for TIME and TIME.com, she pens a feature on language called Wednesday Words and organizes the occasional spelling bee. Her beat is wide but it thumps hardest in the Northwest.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com