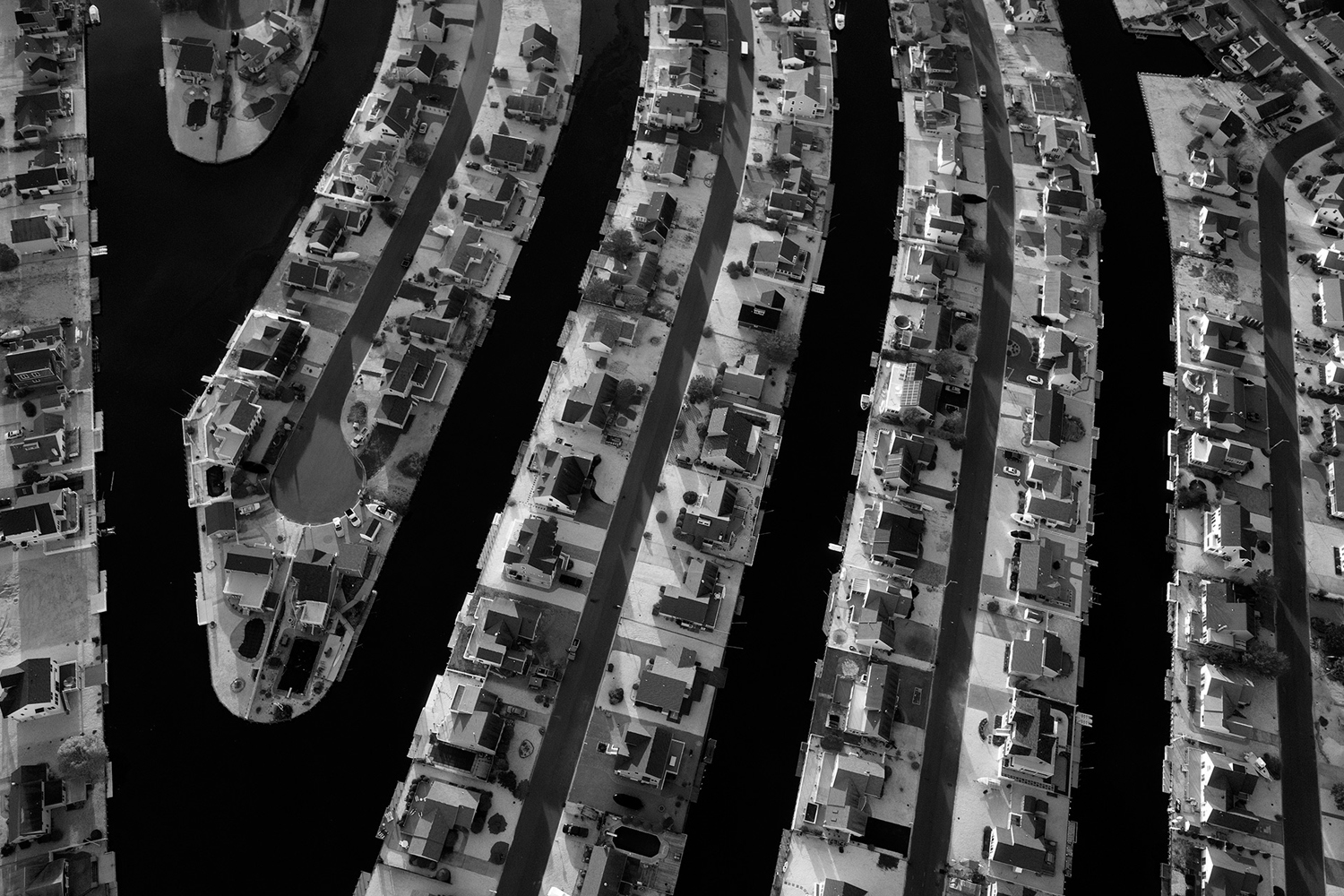

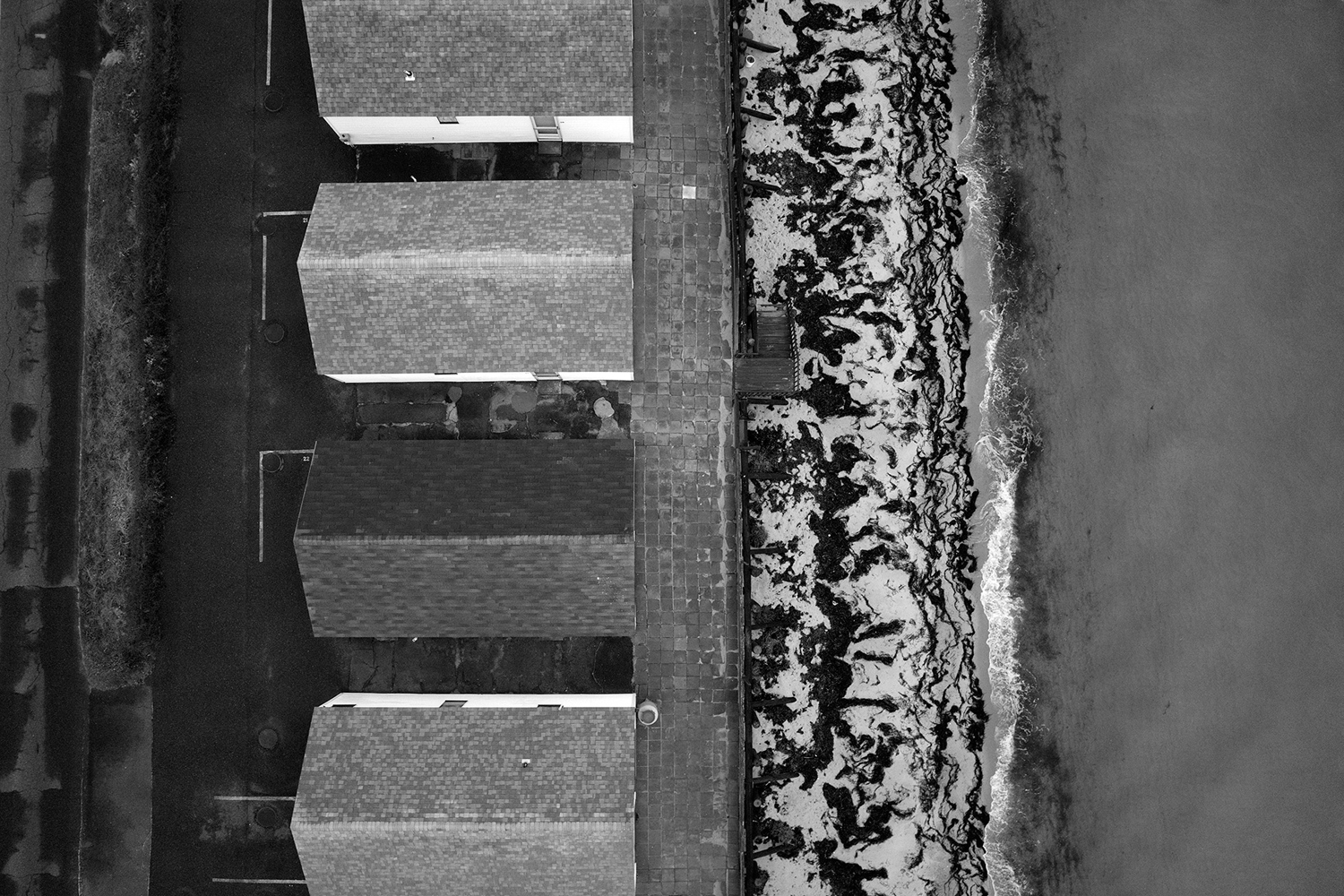

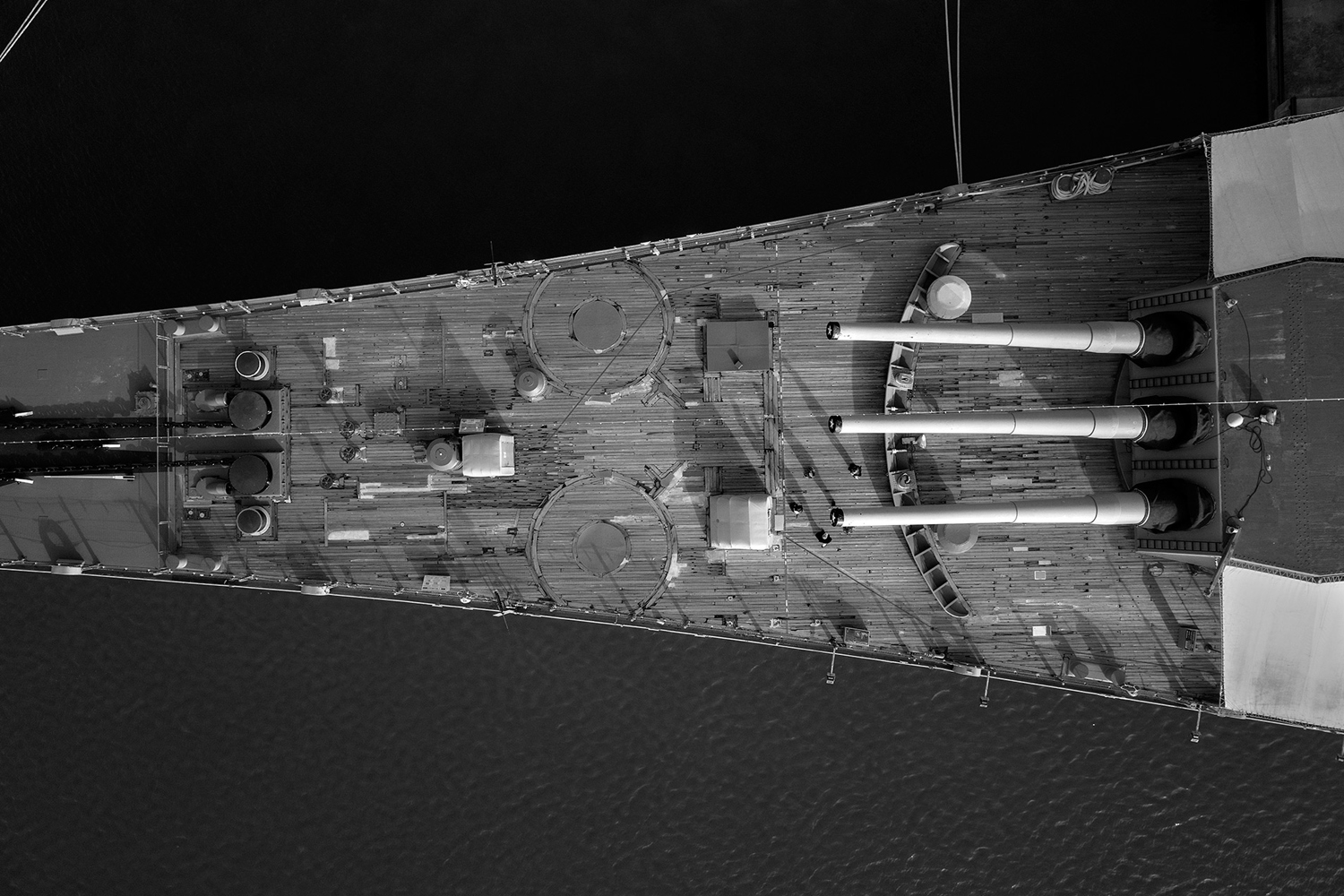

When a drone looks at a thing, that thing has a way of looking like a target. People become silhouettes at a shooting range. Buildings look vulnerable, their roofs helplessly exposed and defenseless. Most colors disappear, and the remaining blacks, whites and greys evacuate the scene of all human meaning. What we see becomes data: body counts, damage reports, strategic value.

In these photos, shot as part of an ongoing series, Belgian photographer Tomas van Houtryve looks at America through the eyes of a drone, a small quadcopter he bought online and equipped with a high-resolution camera. “A drone seems particularly appropriate because it’s increasingly how America views the rest of the world,” he says. “I wanted to turn things around. What do we look like from a drone’s-eye view? Suspicious? Prosperous? Free and happy?” Every age brings with it new technology for looking at the world. Van Houtryve has embraced the technology of ours.

Drones are becoming an increasingly common sight in our domestic airspace. Pilots have started spotting them from airliners: the FAA reports up to 40 cases a month in which drones are seen exceeding the legal ceiling of 400 feet. As they get cheaper, more popular and more plentiful—one online community for enthusiasts, DIY Drones, has over 60,000 members—they are bringing with them a host of unanswered questions, and the White House is scrambling to bring regulatory order to the aerial chaos. In December, the Federal Aviation Administration delayed its long-awaited guidelines on drone flights, initially due next year, until 2017. The questions are about safety, but also about privacy: we’re a lot more comfortable looking through drones than suffering their all-seeing, all-judging gaze.

From this godlike point of view, teenagers playing lacrosse on a field look like lunar shadows of themselves. A housing development in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., takes on an abstract geometric beauty. Everything everywhere looks silent and calm, still and waiting. Even scenes of economic and ecological chaos take on their own serene perfection. In California’s Central Valley, van Houtryve found order in rows of houseboats moored in a reservoir. Rings on the shoreline show how profoundly the water level has been reduced by months of drought.

That same order is echoed by rows of RVs parked near an Amazon fulfillment center near Reno, Nev. (coincidentally, Amazon is where van Houtryve bought his drone). Migrant workers flock there in RVs for the extra jobs that materialize during the holiday season and then, like the water in that California reservoir, evaporate into thin air. In a strange way, the pitilessness in the drone’s stare inspires its opposite in human eyes: empathy.

Tomas van Houtryve is a Paris-based photographer, artist and writer. His reporting on this story was supported in part by a grant from the Pulitzer Center.

Lev Grossman is TIME’s book critic and its lead technology writer. He is also the author of the New York Times bestselling novels The Magicians and The Magician King.

Myles Little, who edited this photo essay, is an Associate Photo Editor at TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com