A lot’s already been written about what the Eric Garner and Michael Brown grand jury decisions reveal about America, and, admittedly, I haven’t read any of it. I’ve left the links unopened, scrolled past the headlines on my social media feeds, dodged Jon Stewart’s instant classic Daily Show (so I hear) rant along with Spike Lee’s Radio Raheem re-enactment. For the most part, I’ve been privately nursing a jarring exchange with a colleague.

“They’re not the same,” I assured my colleague shortly after the Garner grand jury decisions. “Different situations. Different parts of the country. Different grand jury proceedings. Race,” I proposed, “is just the most obvious explanation so we’re all jumping to that conclusion. It’s the easy target,” I announced. “I’d even venture to say there were more differences than similarities in the cases. Besides, we don’t know what evidence the jury heard in the Garner case.”

I thought I was being sensible and critical, not jumping to an emotion-driven conclusion or robotically conflating every incident involving race into the a racist incident. I asked my colleague if she agreed.

She didn’t blink. “No,” she said curtly. “They’re the same.”

I should probably point out here that my colleague is a 30-year-old white woman who grew up in a suburb on the East Coast and I’m a black man pushing 40 who’s faced the wrong end of more than one cop’s pistol and spent the past half-decade writing about racial bias and the law. Yet, curiously, in the moment, she was educating me on the realities of structural racism in America. It was… exhilarating.

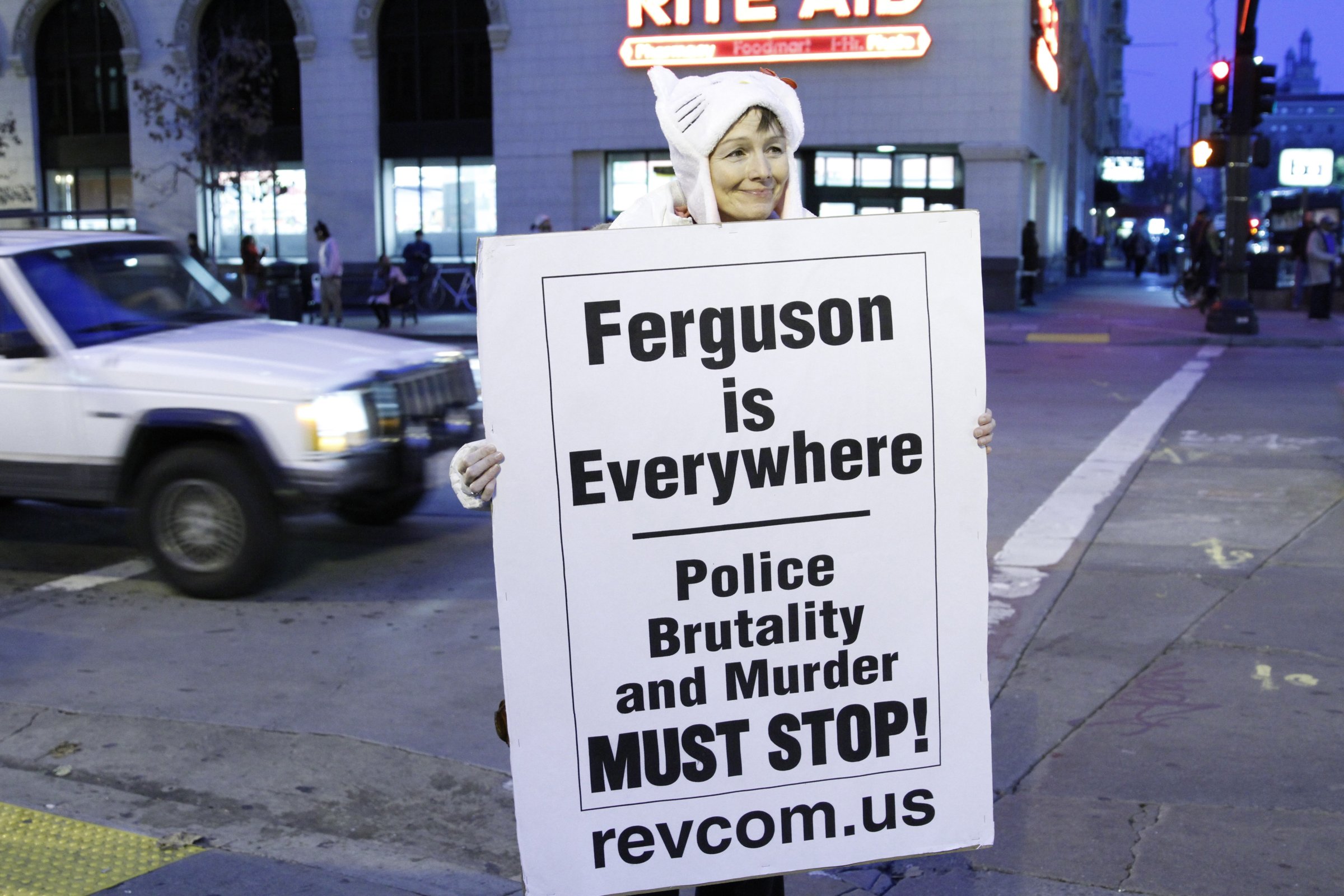

One of the most inspiring aspects of the protests both in Ferguson and New York City has been the presence of white people. For the first time in my lifetime I’ve felt like white people—not just a few friends—really get it. They’re not just sympathizing with black folks and going on about their day (though, of course, many still are). They’re not deflecting the race issue in favor of class analysis. They’re not retreating into white guilt and shame. They’re not pointing to black people who’ve made it or the progress we’ve seen in the last 50 years. They’re demanding racial justice. They’re calling out white cops who walk for killing black men. They’re calling out cowardly prosecutors who game the system to avoid accountability. They’re using the privilege that white skin yields to protect black bodies. Most importantly, they’ve stopped making excuses for a justice system that, in all candor, has relied on their complicity to maintain its aura of legitimacy for so long in the first place.

So the question remains: Why was I reluctant to see the Garner and Brown grand jury decisions as one in the same? And, by extension, why did it take a white woman bluntly calling out what I was trying to avoid to remind me that the evidence of wrongdoing is as plain as day?

On my way home after the grand jury decision I arrived at a possible explanation. Fighting the good fight can be exhausting. After a while, witnessing the same tragic episodes on repeat leaves you feeling defeated. Eventually, you’re left with two options: accept that you can be strangled or shot in broad daylight with impunity or you reject this reality entirely. You develop coping mechanisms just to survive and continue functioning. Without realizing it, you stop believing that the system will ever change. You lower your prospects, narrow your dreams. You do what’s necessary to get your own foot in the door. You play by the rules. You distinguish yourself. You rise.

Pretty soon you find yourself wondering if there’s more than a kernel of truth in the stereotypes about black men. Maybe we are our own worst enemy.… Maybe we aren’t trying hard enough. You strive to become so special, so unique, that the rules that apply to other black men won’t apply to you. You become an esteemed professor, world-class athlete, President of the United States. You try like hell to purchase an exemption. Time passes and while you may not contract full blown Stockholm Syndrome, you start justifying the unjust. He must’ve done something to provoke the cop.… Why was he selling cigarettes anyway? … Why didn’t he just get down on the ground when that cop told him to? You start apportioning blame like an insurance agent. Maybe the cop was 80% in the wrong, but the victim was at least 20% in the wrong. You train your mind to look at situations where race is involved in an “objective” manner because you don’t want to be perceived as an overly sensitive minority who blames everything on race, because that undermines your credibility among your colleagues and peers and threatens the rational foundation you’ve built your life on.

Accepting that Eric Garner and Michael Brown are one in the same was too much for me. The implications were too distressing. If everything I’d built could be taken away at so little cost, then what was the point? Why did I bother? My only alternative was to diminish the role that race played, look for other explanations.

As trivial as it may seem, my colleague’s brusque rebuff nudged me out of my sense of futility. Sometimes things are exactly what they appear to be. Witnessing so many white allies protesting in the name of black lives has had a similarly uplifting impact on me. Of course, the thought has crossed my mind that, on some level, the presence of whites gives the protests an aura of legitimacy in the eyes of mainstream America. But, maybe, I’ve just waited all my life to see white people as fed up with racism as I am.

Dax-Devlon Ross is the author of five books, a contributing writer for Next City Magazine and a nonprofit education consultant. You can find him at daxdevlonross.com.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Behind the Scenes of The White Lotus Season Three

- How Trump 2.0 Is Already Sowing Confusion

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- We’re Lucky to Have Been Alive in the Age of David Lynch

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Column: All Those Presidential Pardons Give Mercy a Bad Name

Contact us at letters@time.com