The Yezidis – one of Iraq’s oldest and most secretive sects – believe that following the great biblical flood, Noah and his ark came to rest on Mount Sinjar, a range of mountains that run parallel to what is, today, the border between Iraq and Syria. But, for up to 50,000 of Iraq’s Yezidis, this sacred land has become a deadly prison.

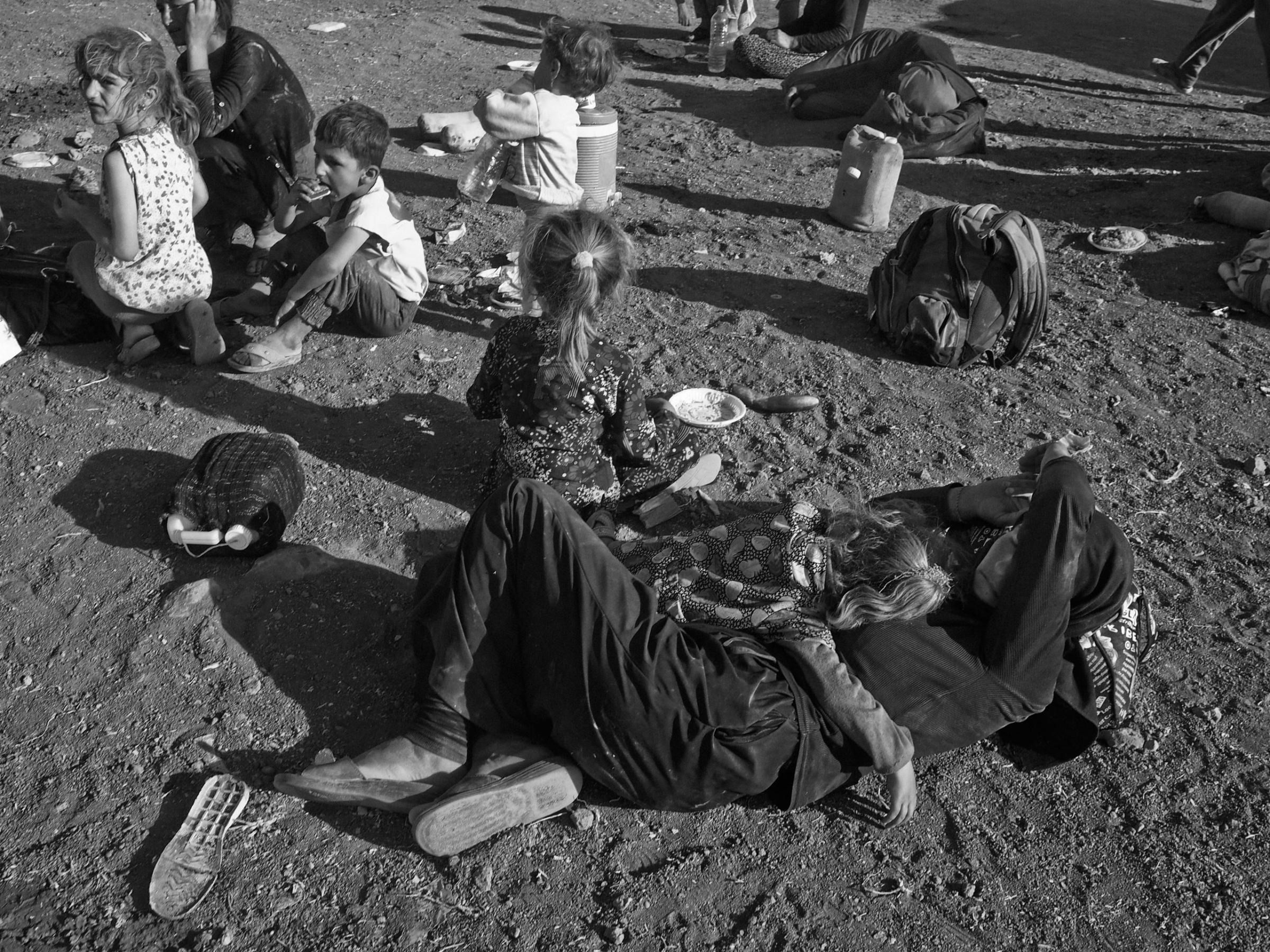

Forced from their homes by militants of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), the Yezidis – most of them women, children and elderly – were given two choices: face certain death at the hands of fanatics or flee to the uncertain refuge that is Mount Sinjar.

“It’s a spectacular mountain range,” says Magnum photographer Moises Saman, who was on assignment for TIME this week. “Everything is flat and suddenly, you see these mountains pop out of nowhere. On one side you have the town of Sinjar, where most of the refugees are coming from, and on the other side, there’s Syria.”

With temperatures reaching 100 degrees, the conditions on the Sinjar Mountains are dire. Most of the Yezidis ran for the hills without food and water. “That’s why it’s been such a dramatic situation for them,” says Saman. “Without supplies on a mountain like that, nobody can survive more than a couple of days.”

Kurdish fighters from Iraq and Syria have been trying to establish a humanitarian corridor to provide relief to the thousands of trapped Yezidis, but their resources are limited. “They are using two or three old and rusty, [Soviet-era] helicopters,” says Saman. “There hasn’t been a mass airlift effort – there’s not that much aid that’s getting there, and that’s one thing that I was surprised about.”

While the U.S. sent 130 military advisers Tuesday to help repeal ISIS’ forces, the Yezidis continue to endure their ordeal. “I would think that by now there would be more of an international, concerted effort to help them, but I haven’t really seen it,” says Saman. “I think the Kurdish authorities are doing their best with what they have.” And that’s not much, especially after these militias lost one of their helicopters on Aug. 12, when it crashed with refugees and journalists on board.

“When I first saw the helicopter, the thought obviously crossed my mind, ‘Oh man. I hope nothing happens’. But it happened,” says Saman, who boarded the doomed helicopter at a Peshmerga [Kurdish forces] base on the outskirts of Fishkhabur, in Iraq’s Dohuk province.

“We flew in with supplies – bread, water, bananas, ready-to-eat meals,” he explains. “The situation was chaotic because people, obviously, were trying to get in. I was standing in the middle of this group of refugees, holding on with one hand and taking pictures with the other when the helicopter lifted up. I just lost track of time, but it couldn’t have been more than a minute when it banked to the right and crashed into the side of the mountain.”

Then, everything turned black. “The next thing I remember [was the thought] that I was still alive,” says Saman. “I felt that nothing was hurting, but I was pinned down [by the weight of some of the other passengers]. It was very hard to breathe, and I just couldn’t move. At that point, I really thought I was going to asphyxiate.”

One of Saman’s colleagues, freelance photographer Adam Ferguson, who suffered minor injuries, was able to help him up. “Most of the passengers were hurt, several of them badly. And the pilot was dead. Everyone was in a state of shock.”

It took an hour before another helicopter was able to rescue them. In that time, Saman was able to photograph the crash’s immediate aftermath. A few hours later, after receiving three stitches at a hospital in the city of Dohuk, he filed his work, which were first published in color as news broke of the crash. But, says Moises, “when I started talking with TIME about this assignment, I really saw it as a black-and-white story,” he explains. “I wanted to give a sense of timelessness to the situation because, one way or another, the Kurds have been refugees for decades. We’ve seen these scenes of Kurds stuck in the mountains back in the 1980s and ’90s, and now it’s happening all over again.”

Like many photographers who have covered humanitarian crises before, Saman hopes his images will force authorities into taking action. “I hope people will realize how bad the situation is for these people, I also hope that they will find a way to relate somehow,” he says. “I know it’s going to be difficult because these things don’t often happen in the West. But, it’s such a dramatic and sad situation.”

Moises Saman, on assignment for TIME, is an award-winning photographer represented by Magnum Photos.

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com