Photographer Peter DiCampo and writer Austin Merrill never intended to start an international movement when they launched Everyday Africa in early 2012. Their initial goal was to act against the visual clichés and stereotypes about war, poverty and disease that permeate conventional media coverage of Africa. “As journalists who are native to Africa or have lived and worked on the continent for years at a time, we find the extreme not nearly as prevalent as the familiar, the everyday,” they explain.

Everyday Africa started as a Tumblr account with DiCampo and Merrill sharing the Hipstamatic cell-phone images of everyday life they had shot across Africa on their various assignments. For a few months, the project attracted modest attention—until its founders opened an Instagram account, transforming the project’s entire publishing and distributing processes.

Today, Everyday Africa has more than 95,000 followers and has spawned numerous spin-off accounts in Asia, Latin American, the Middle East, the U.S., Iran, Egypt, and even in the Bronx, where photographers are working to dispel the stereotypes that have come to define these places.

Next month, DiCampo will be bringing these photographers together in a global exhibition at the Photoville festival in New York. “The exhibition is going to be the first time that many of the Everyday projects will be exhibiting in the same place,” DiCampo tells TIME. “It’s also the first time a bunch of the people involved will be in the same place. It happened out of the blue: Pamela Chen, the Editorial Director at Instagram, and Teru Kuwayama, Facebook’s photo community manager, offered to host the exhibition.”

The exhibition will mix together images from the Everyday Africa account with work from the “official” Everyday feeds that have sought to link up with DiCampo and Merrill’s project in the past year. The organizers hope to show that anyone armed with a cell phone can now play a part in how a region and its people are represented through photographs. Earlier this year, Everyday Africa started welcoming submissions from non-photographers—pictures that are then curated and published on the project’s website.

“The first thing that comes to my mind with that type of show is the Family of Man exhibition,” say DiCampo, referring to Edward Steichen’s celebrated 1955 Museum of Modern Art show, which went on the become the most-travelled exhibition in the history of photography. “Obviously it’s not on that scale. But to me, the kind of work we’re doing is a modern update to that exhibition, especially considering it’s cell phone photography and it’s distributed through social media.”

For DiCampo, the exhibition is also a unique opportunity to bring the managers of the different Everyday accounts together to put on paper the core ideas that define the movement, as he calls it. More importantly, he believes they have a responsibility to establish best practices in an industry that has been deeply affected by the democratization and popularity of cell phones, but has, for the most part, failed to act in unison.

“I think we have a voice to talk about what cell phone photography is and to try, in some way, to lead the discussion on rights, usage and [the like],” he says. “You’ll see us coming out of this meeting with some sort of declaration of how we feel cell phone photography should be used and what the rights of photographers are.”

In the meantime, DiCampo will continue to encourage photographers to expand the Everyday movement. “I want people to use this anywhere they feel it’s needed to change people’s perceptions,” he explains. “Whether that’s a continent, a country, a city or a neighborhood, it’s really up to the person who has chosen to take that on.”

And, he adds, using a streaming feed as offered by the Instagram interface can only heighten the impact. “That idea of the stream as the narrative, which is what most social media platforms are built to be, is interesting. The stream as a narrative form addresses the issue of representation. You scroll through the images and you see the problems and the positive stuff, side-by-side. It reminds people that all these things happen simultaneously. And that’s the part that we often forget.”

The Everyday exhibition is on at Photoville from Sept. 18-28 at Pier 5, Brooklyn Bridge Park in New York. DiCampo will lead a panel discussion on The Everyday Movement and the Uphill Battle Against Media Stereotypes on Sept. 21. Below, we profile some of the different Everyday Instagram accounts that will be featured in the exhibition.

Everyday Eastern Europe (@everydayeasterneurope)

Eastern Europe is often represented in the media as bleak and grim, “with crumbling buildings and old people drinking and [looking back fondly] on Soviet times,” Latvian photographer Tina Remiz. Inspired by DiCampo’s endeavor, she launched Everyday Eastern Europe on Instagram. “These are some of the stereotypes we try to challenge,” she says. “Personally, I find it fascinating how the recent past and present exist side by side in this part of the world—I think it offers some striking visual juxtapositions,” which have translated into the account accumulating more than 2,700 followers in the last six months.

Defining what constitutes Eastern Europe was challenging, though. “It’s not a continent,” says Remiz, “so we had, and still have, a lot of debates defining the borders. I look at it from a cultural, rather than geographical perspective, as there are certain features that unite all these places, such as the Slavic language or our recent Communist past.”

The account is staffed by 12 photographers including Amanda Rivkin, Matt Lutton, Brendan Hofman, Fabian Weiss, Lesya Polyakova and Davin Ellicson. “The two defining factors [in selecting contributors] are talent and personal skills,” says Remiz. “Ideally, I’m looking for someone able to produce amazing images, as well as being organized and proactive, contributing work regularly, coming up with new ideas and helping us spread the word and grow the account. We also look for other ways to collaborate with photographers who don’t meet these criteria, featuring, every Friday, work from our followers hashtagged with #everydayeasterneurope.”

Everyday Latin America (@everydaylatinamerica)

“Everyday life in Latin America is full of contrasts,” says Elie Gardner, a former staff photographer at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and creator of the Everyday Latin America Instagram account. “[Life here] is loud and quiet, colorful and drab, hot and cold. It varies as much within a country as it does from country to country. Everyday life for a poor migrant living in Lima looks very different from the life of a banker who lives in a penthouse in Mexico City.”

Gardner, who relocated to Peru in 2010 with husband and photojournalist Oscar Durand, felt she had to join Instagram when the service launched that same year. “As freelance photographers, Instagram is one of the few outlets we have to share feature photographs,” she tells TIME. “Before blogs and Instagram, many of these images sat in negatives sleeves and on hard drives. It’s rare to see a nice slice-of-life photograph from regions such as Africa, the Middle East and Latin America in a U.S. paper. Instagram gives us unlimited space to share our everyday lives with the world, and if you dwell on that concept, it’s pretty powerful.”

The @everydaylatinamerica account has a long list of contributors—Orlando Barría, Oscar Castillo, Patricio Crooker, Felipe Dana, Oscar Durand, Ana Carolina Fernandes, Tatiana Fernández, Elie Gardner, Claudio Gutierrez, Francisco Mata Rosas, César Morejón, Janet Jarman, Alejandro Kirchuk, Meridith Kohut, María Madgalena, Gil Montaño, Federico Pardo, Luis Sergio, Danielle Villasana and Adriana Zehbrauskas, Christian Ugarte and Marie Arago—which has made it difficult to manage for Gardner and Durand. “We knew we couldn’t do it alone, so we co-curate the feed with Lima-based photographer Danielle Villasana and Bogota-based photographer Federico Pardo.”

The moderators haven’t set up a list of “dos” and “don’ts” for their contributors, but there’s one restriction: “All of the photos must be taken with a mobile phone.”

Everyday Middle East (@everydaymiddleeast)

“It should go without saying that every society has an ‘everyday’,” says Lindsay Mackenzie, the manager of the Everyday Middle East Instagram feed. “But Western media coverage of the Middle East tends to edit that out in the process of selecting which stories to tell.”

The Canadian photographer was based in Tunisia for two years covering the Arab Spring revolts, and she quickly realized that media representation of the region was skewed towards negativity. “I could only sell images of bearded Salafi men protesting and women wearing niqabs,” she says. “I found that troubling, [and I felt] I was part of the problem; part of the dehumanization of the region. I think that if we, in the Western media, ignore everything except the most extreme people and issues, the overall image that outside viewers get is not accurate, not balanced, and reinforces stereotypes. It goes against what we are supposed to be doing.”

Working with 24 contributing photographers, Mackenzie has included “a broad set of countries that are subject to a similar set of ‘Middle East’ stereotypes,” from Morocco to Iran, Turkey to Palestine and Yemen. The feed also includes images shot in Israel.

The rules to post on the Everyday Middle East feed are simple: only mobile phone images, and “stay away from too many breaking news and wire-type images, because the point of the feed is to show what exists beyond that—to illustrate the context within which the extreme images that we see in the mainstream media exist,” says Mackenzie. “Personally, I think we’re at our best when we can show images that are intimate, like Dalia Khamissy’s image of a gay Syrian couple sitting together at a home in Beirut. Or images that are unexpected, like David Degner’s photo of a polo match in Cairo. Or those that show common human experiences, like Hanif Shoaei’s elegant photo from behind the scenes at a wedding in Tehran.”

Everyday Asia (@everydayasia)

“As a freelance photographer, it often feels as if we operate in a vacuum,” says India-based photographer Ian Thomas Jansen-Lonnquist. “We have no office and no co-workers that we see regularly. So to connect with our peers, all we have are festivals and workshops. What I have come to value most of all about the Everyday phenomenon is the connections I’ve made with other photographers, within Everyday Asia and now with the founders and contributors that make up the other feeds.”

Jansen-Lonnquist created Everyday Asia a year ago. “At that time, I was working alone in a remote area of India that has a reputation for conflict, drugs and diseases, but in my six months living there I found a rich art, sport, theater and music culture. People were more welcoming, caring and community-minded then in many of the places I’ve ever been before.”

Armed with three simple rules—“no selfies, no screenshots, and no DSLR photography”—Jansen-Lonnquist looked for photographers who had shown a commitment to using mobile phone photography and Instagram in their work. “I also wanted to make sure I had a balanced mix of local and foreign photographers, [male and female], and with a variety of backgrounds within photography.

Unlike Everyday Africa, whose aim was to dispel negative notions, Everyday Asia faces the opposite problem, says Jansen-Lonnquist. “Asia tends to be portrayed as [this exotic place]—the colors, spices, clothing. So our job really is to bring our followers into the lives of people who make up our communities.

Everyday USA (@everydayUSA)

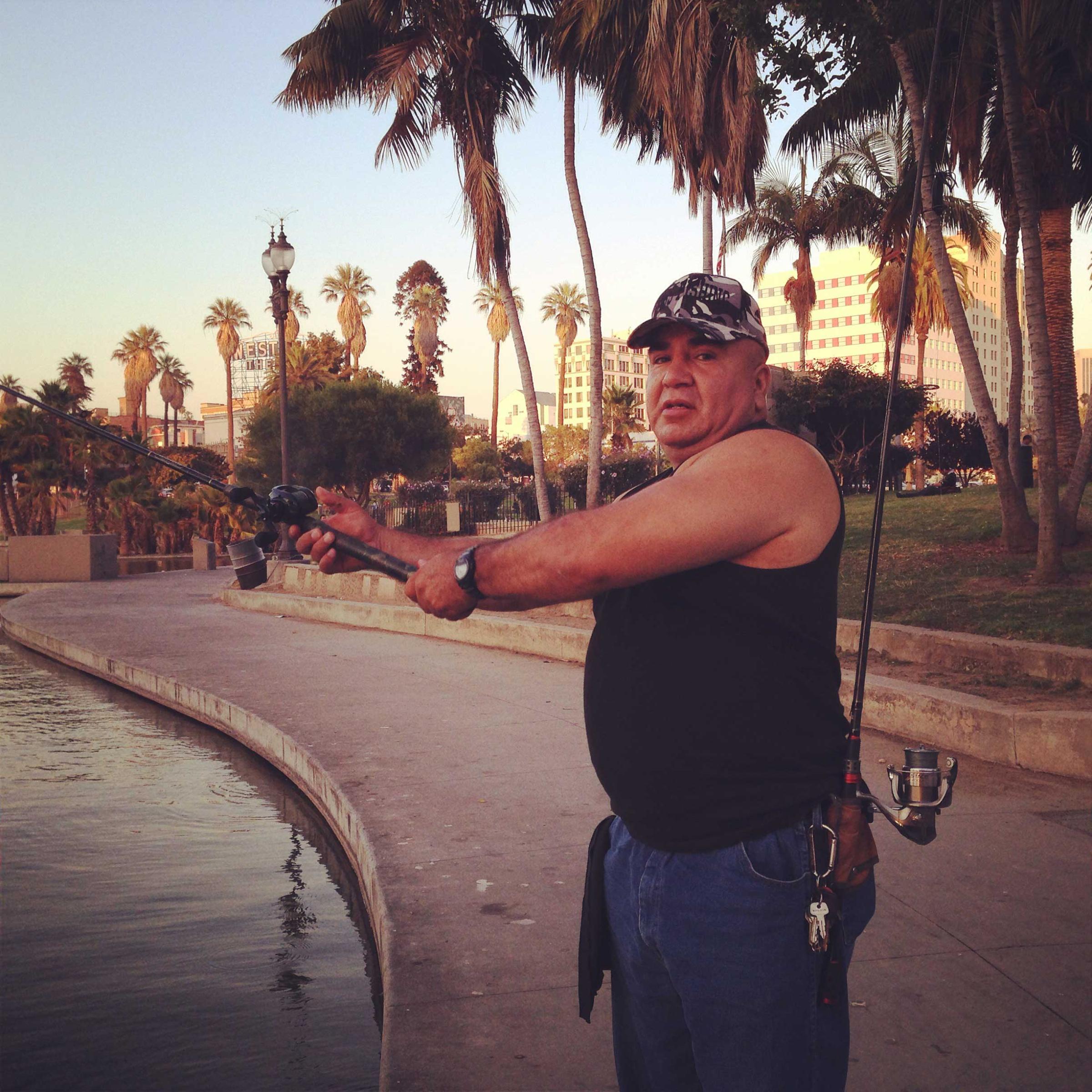

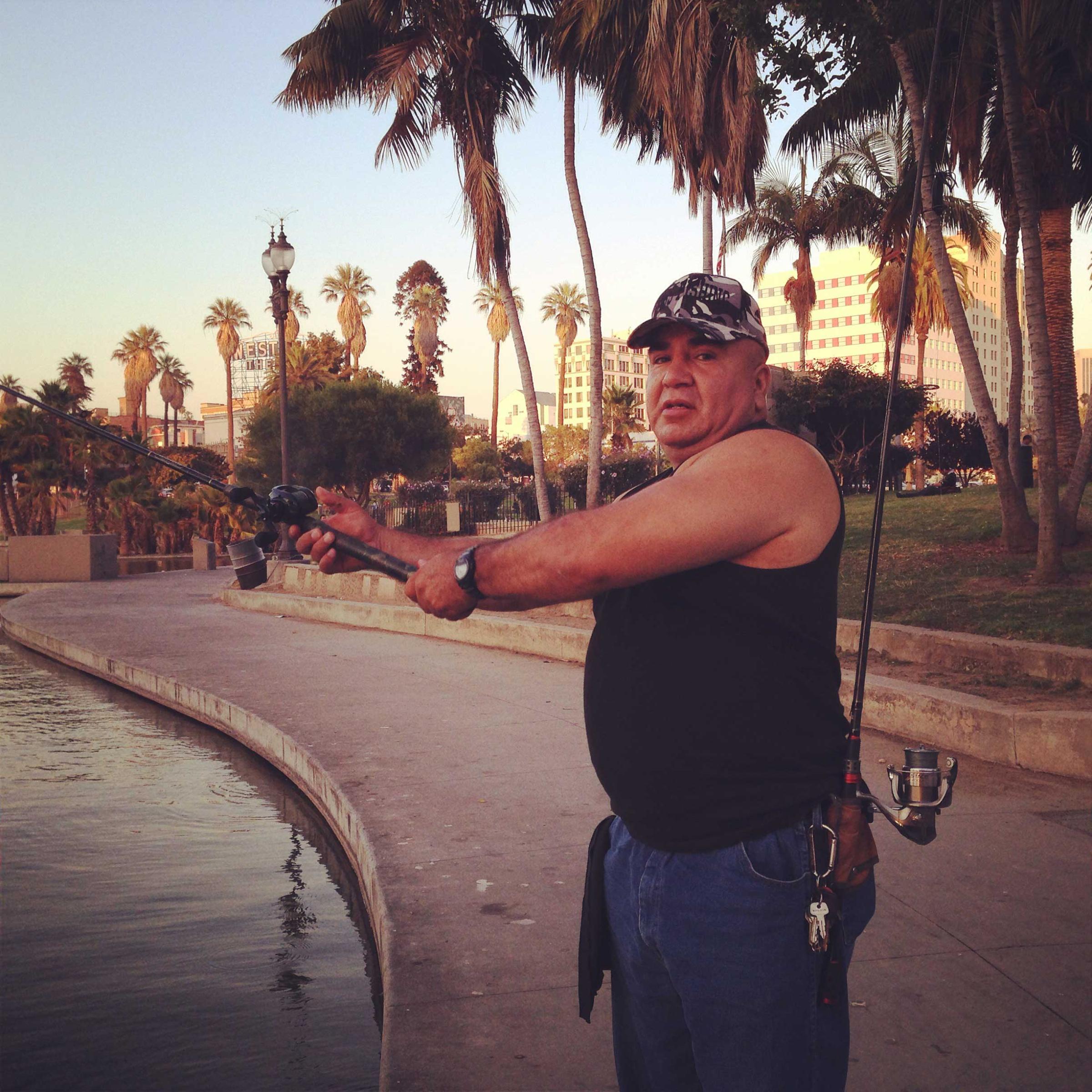

Launched on the 4th of July by former Associated Press photographer David Guttenfelder, Everyday USA takes a different approach to the “Everyday” formula. “We have a tradition of feature photography in our newspapers so I don’t think that portraying the everyday—the normal, the happy—is the problem in the U.S.,” Guttenfelder told National Geographic. “The Everyday USA feed is about trying to photograph things that people overlook or refuse to see, things that come from places that they don’t go or they don’t know about.”

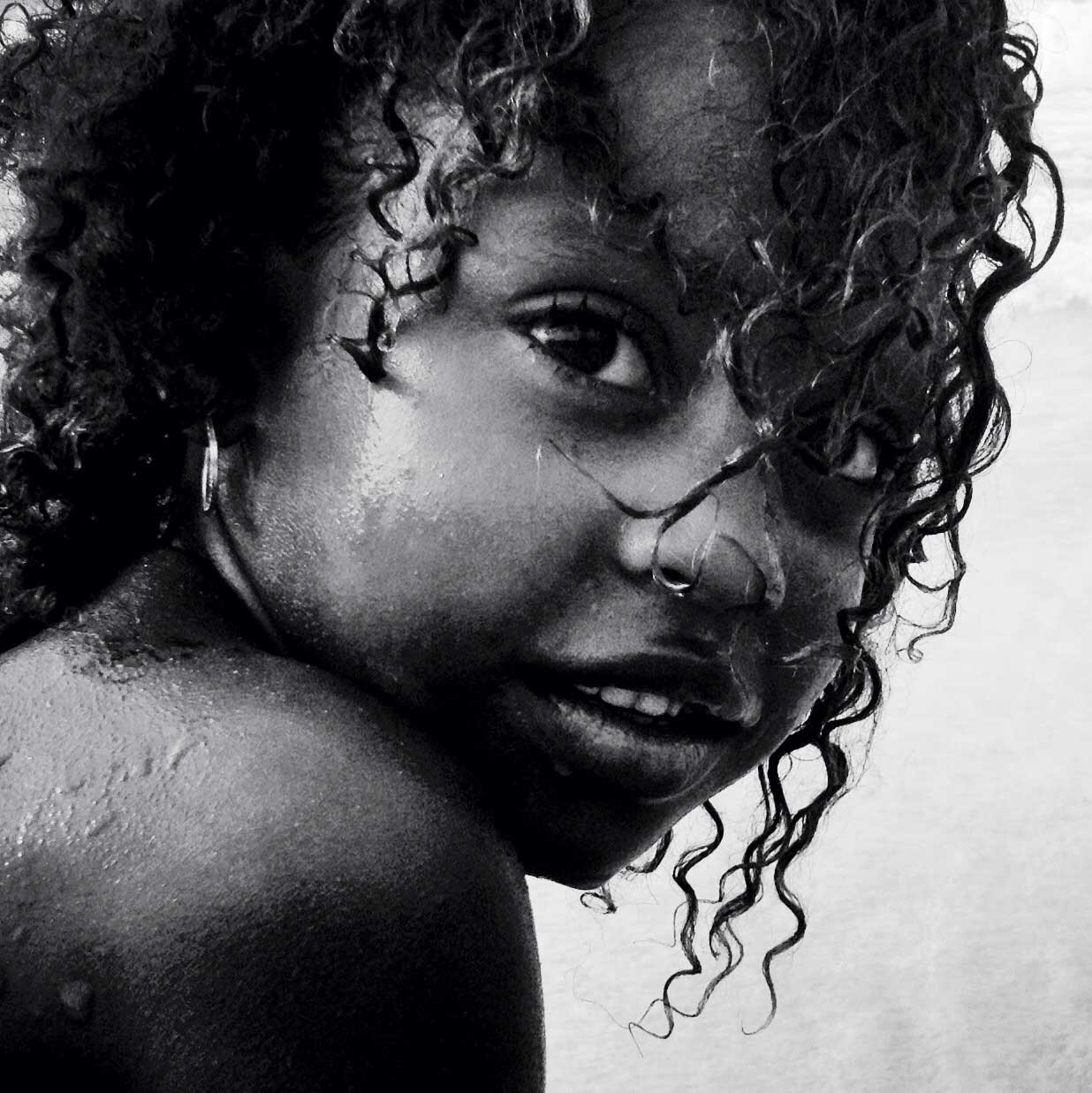

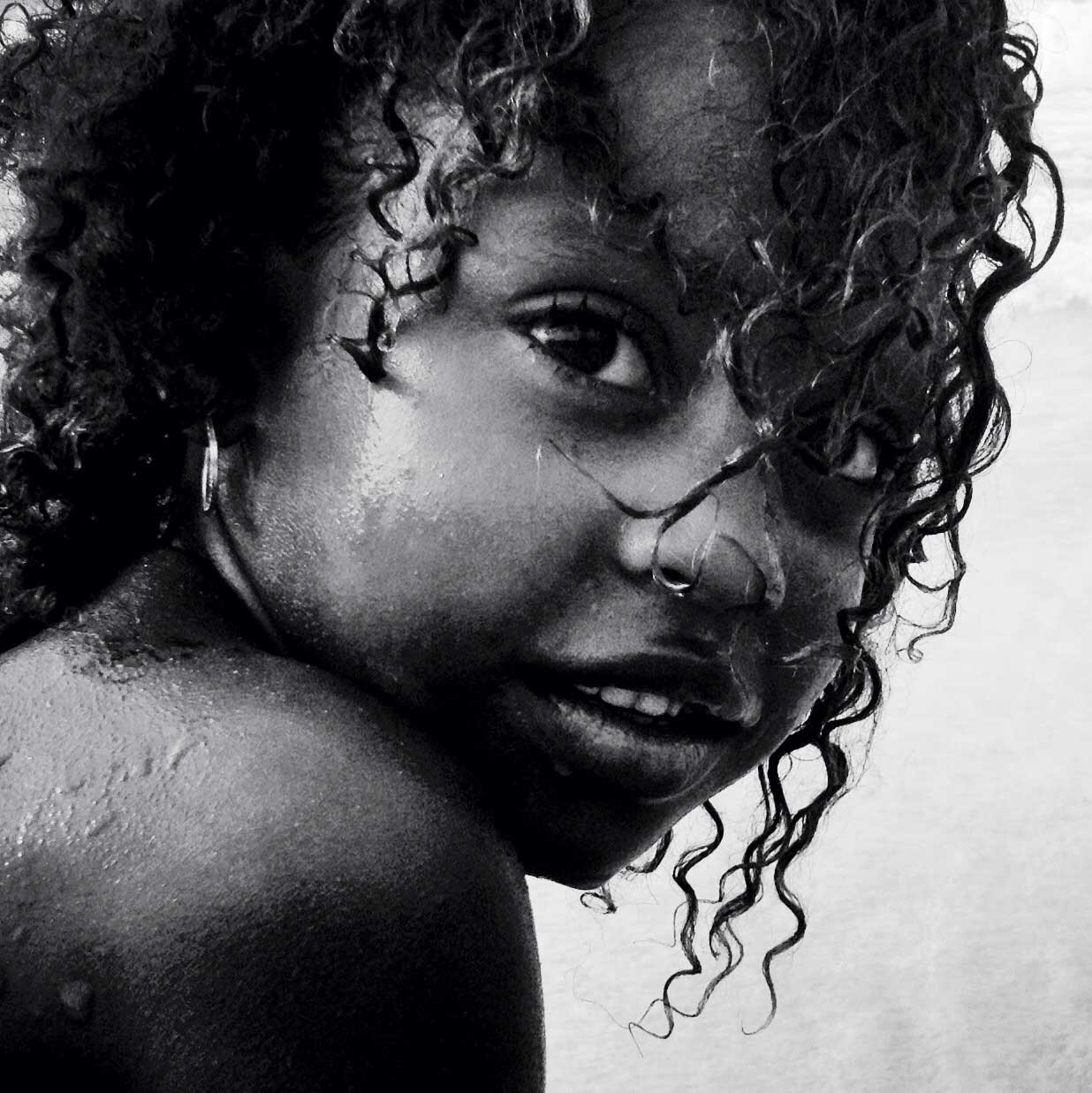

Everyday USA also distinguishes itself from other feed for its mix of contributors, who all come with different styles and approaches to photography—from pure photojournalism with Jon Lowenstein to a more artistic approach with Alec Soth. Other photographers include Nina Berman, Matt Black, Malin Fezehai, Danny Wilcox Frazier, Balazs Gardi, Krisanne Johnson, Stacy Kranitz, Miki Meek, Jared Moossy and Ruddy Roye. “Our hope is that through many voices we’ll create a collective view of the country,” Guttenfelder said.

Everyday Iran (@everydayiran)

Everyday Iran’s feed is an open platform for Iranians, says photographer Ramin Talaie, who manages the Instagram account. “We ask people to tag their images with the #everydayiran hashtag and then we select the best images which, after a group review, are published to our feed.”

The goal, as with most Everyday accounts, is to create a visual narrative that goes against the established Iranian stereotypes. “The typical media portrayal of Iran is mostly about anti-U.S. and anti-West demonstrations and politics,” says Talaie. “We hope that people following our feed are able to see something different and even a little more intimate. We show both the inner life of Iranians and what is seen in public.”

The feed has attracted particular attention since the feed obeys some of Iran’s strict rules on what can and cannot be shown in pictures. “There are the so called ‘red lines’ that we do not cross and our contributors act the same way. For example, we do not show women in bathing suits. However, there are still images that are surprising to some of us. Last week we published a photo of a woman selling make up in a women-only metro car in Tehran. That image was unique.”

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent

Follow TIME LightBox on Facebook.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com