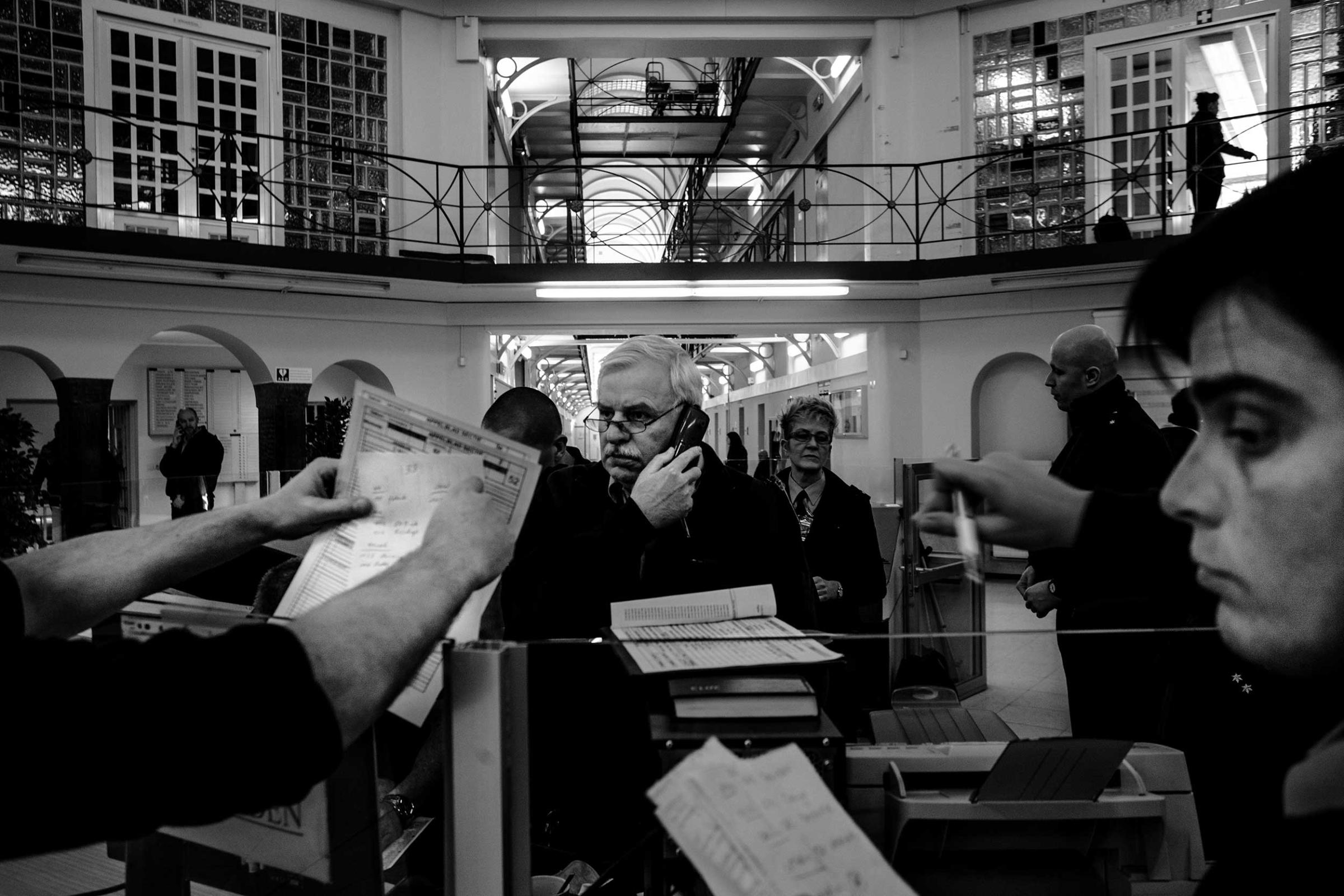

“My goal was to show the reality of these places, without the photographic clichés,” says Belgium photographer Sebastien Van Malleghem, who, for the past three years, has gained access to and photographed everyday life inside his own country’s prisons.

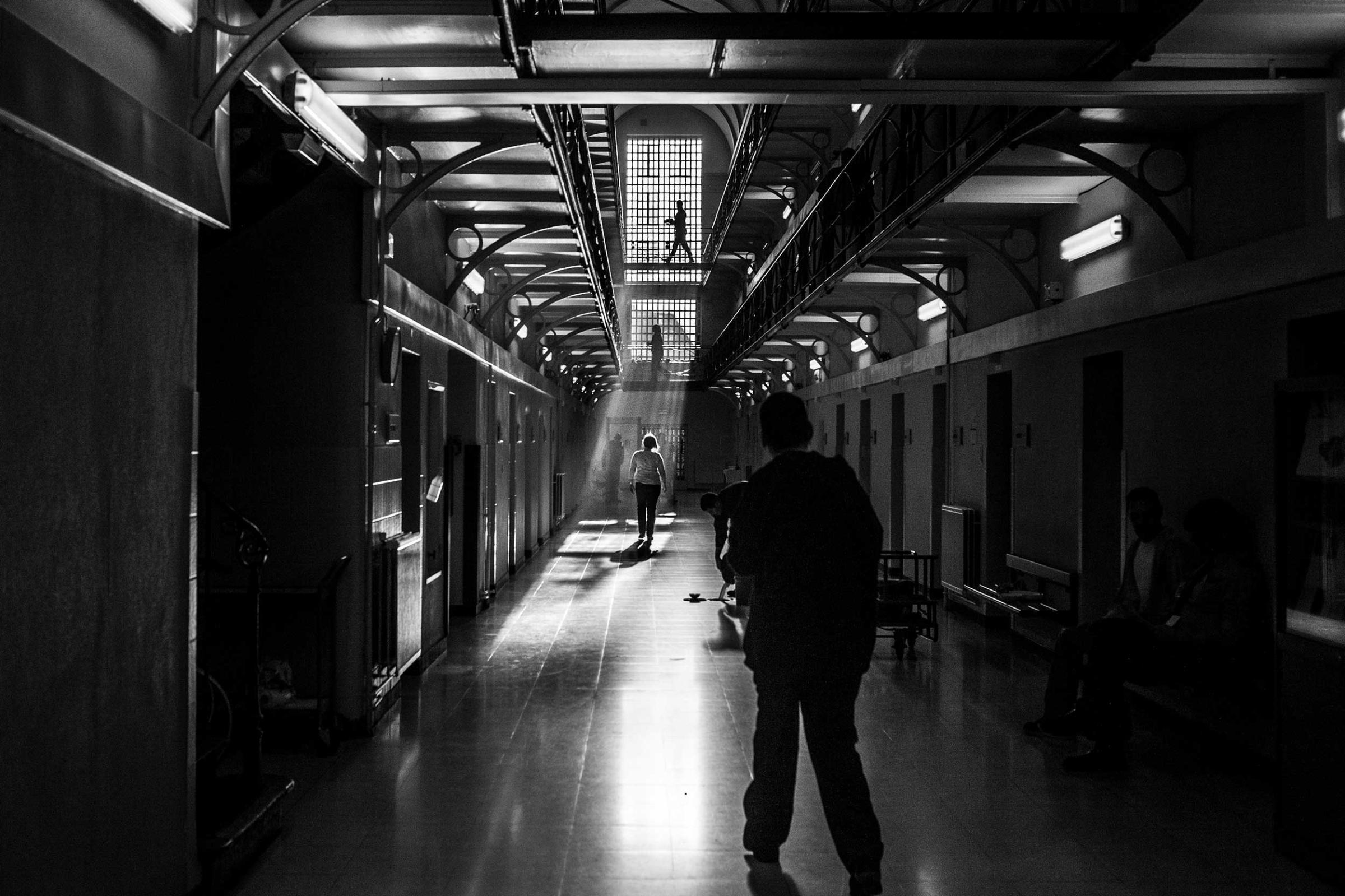

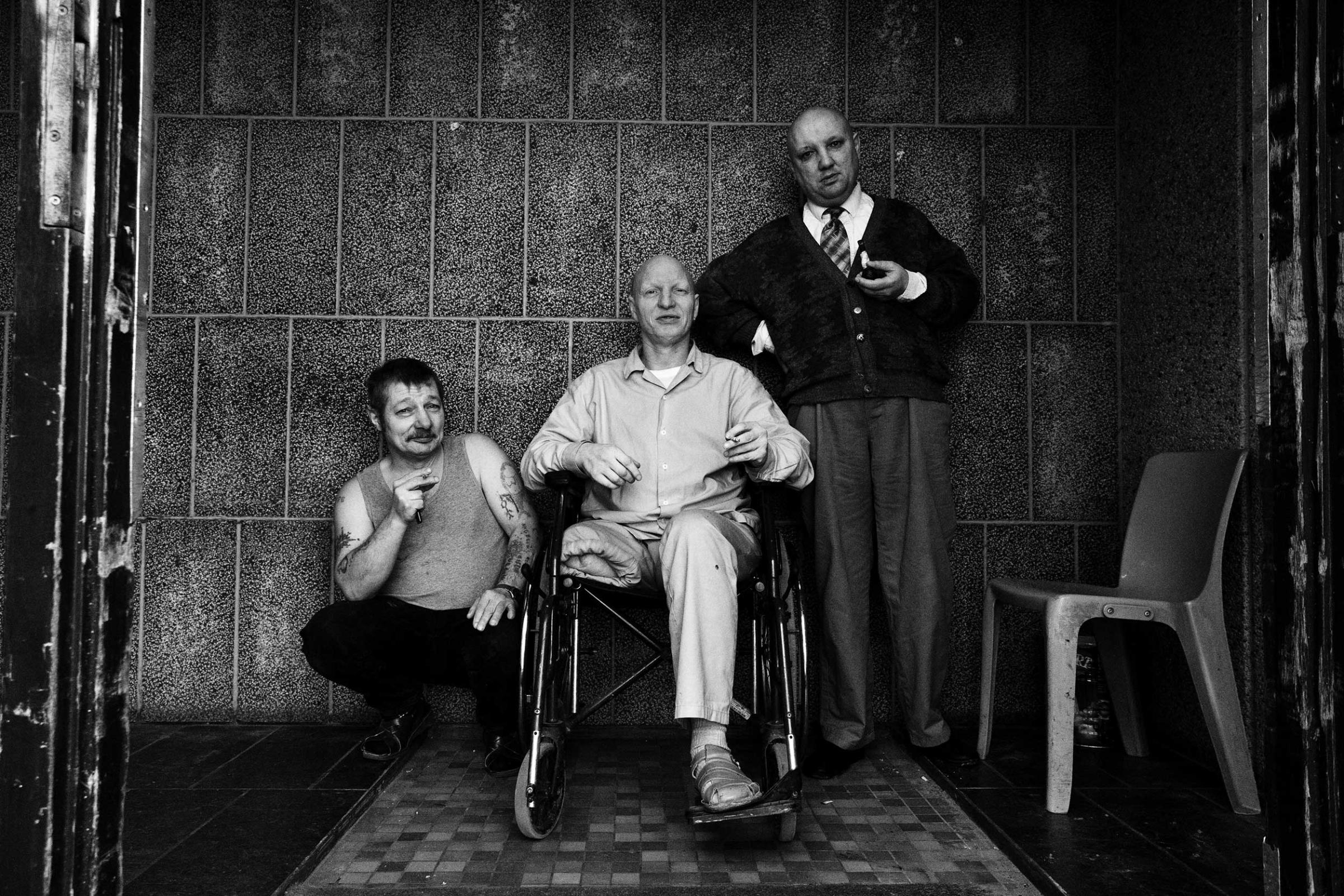

“These [penal] universes have been photographed many times before, but I was more interested in the psychological oppression created by these places,” Van Malleghem tells TIME. “Being locked up is a form of punishment, but once you’re inside you realize it’s just the beginning. There are many other forms of punishment—psychological and emotional ones. Once you’re in this box, they put you into another smaller box where your movements, your spirit and your ideas are confined.”

The 28-year-old photographer’s curiosity towards his country’s penal system came after four years spent following police officers for his Police project. “I wanted to start a story on justice and violence in Belgium, and I felt that the first step would be to follow the police.”

Van Malleghem readily admits that, as a younger man, he was attracted to this world of violence. It’s only after he finished that earlier project that he shifted his focus to another form of violence—namely, “a social violence; the one embodied in the relationship between a state, which is represented by these policemen and prison guards, and citizens. I wanted to see how a government sentences its own people.”

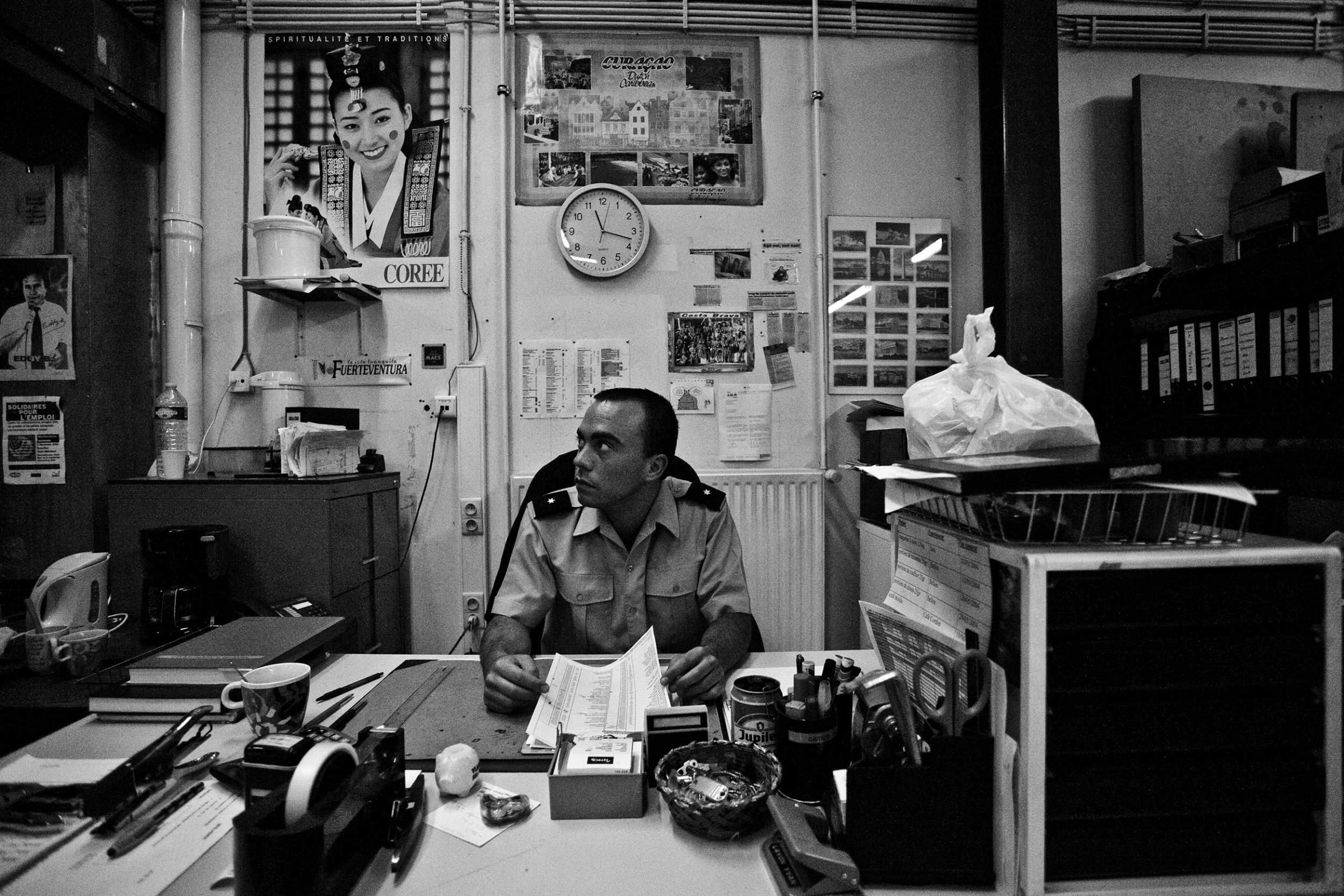

Gaining full access to these prisons, however, proved difficult. “It took me six to eight months to get permission from the Belgian government,” says Van Malleghem. “Once I received that general authorization, I still had to approach and convince prison directors to open their doors to me.”

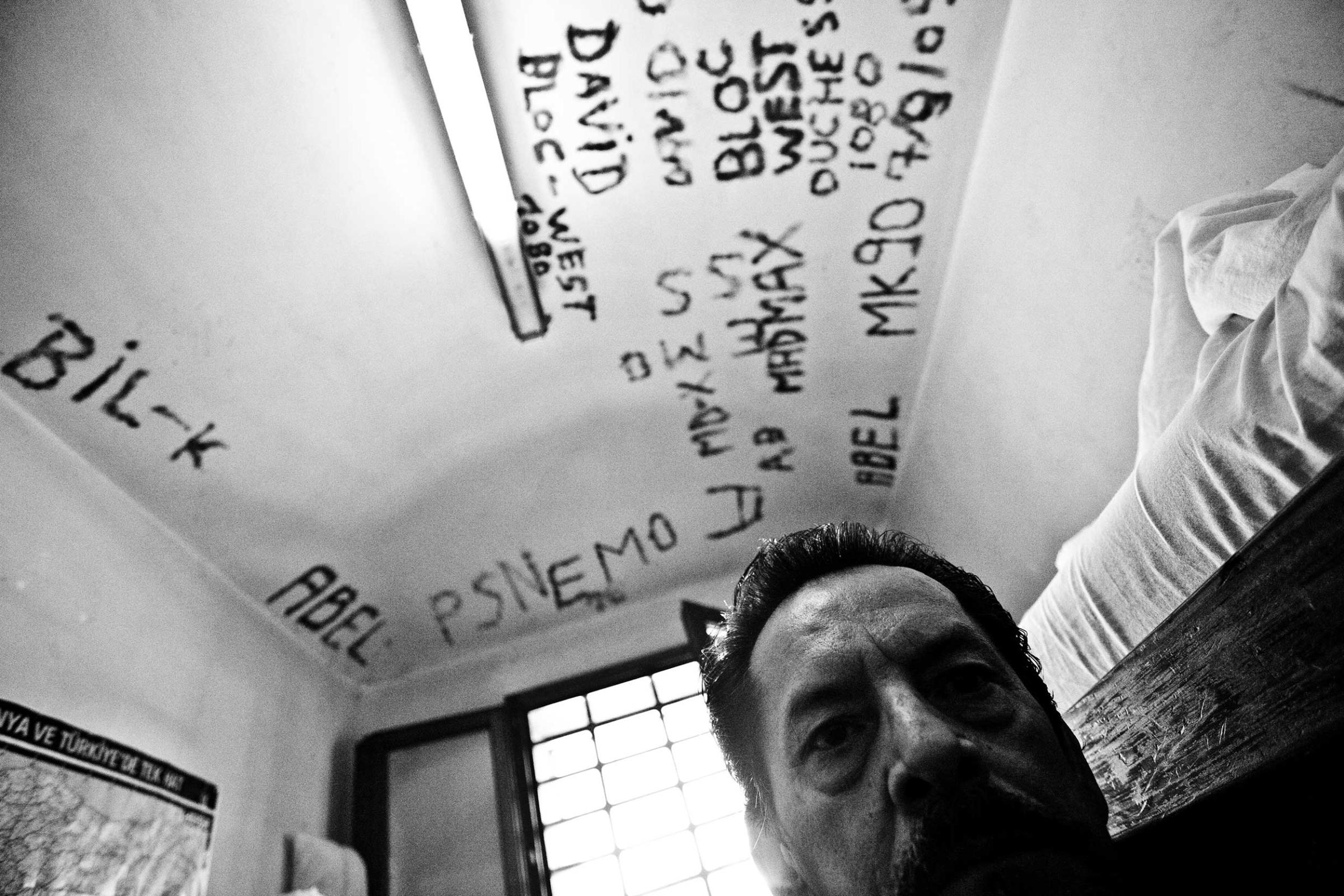

Most prisons couldn’t afford to dedicate resources for Van Malleghem’s project beyond just a few hours. “I had to be followed by a guard,” he notes. But, in some cases, the photographer was able to spend up to three months in the same place. “For some directors, my work represented a way to raise awareness about the state of their prisons,” he adds. “With the economic and social crises, the Belgium government doesn’t really have the budget to help renovate these prisons, some of which were built in the 1800s.”

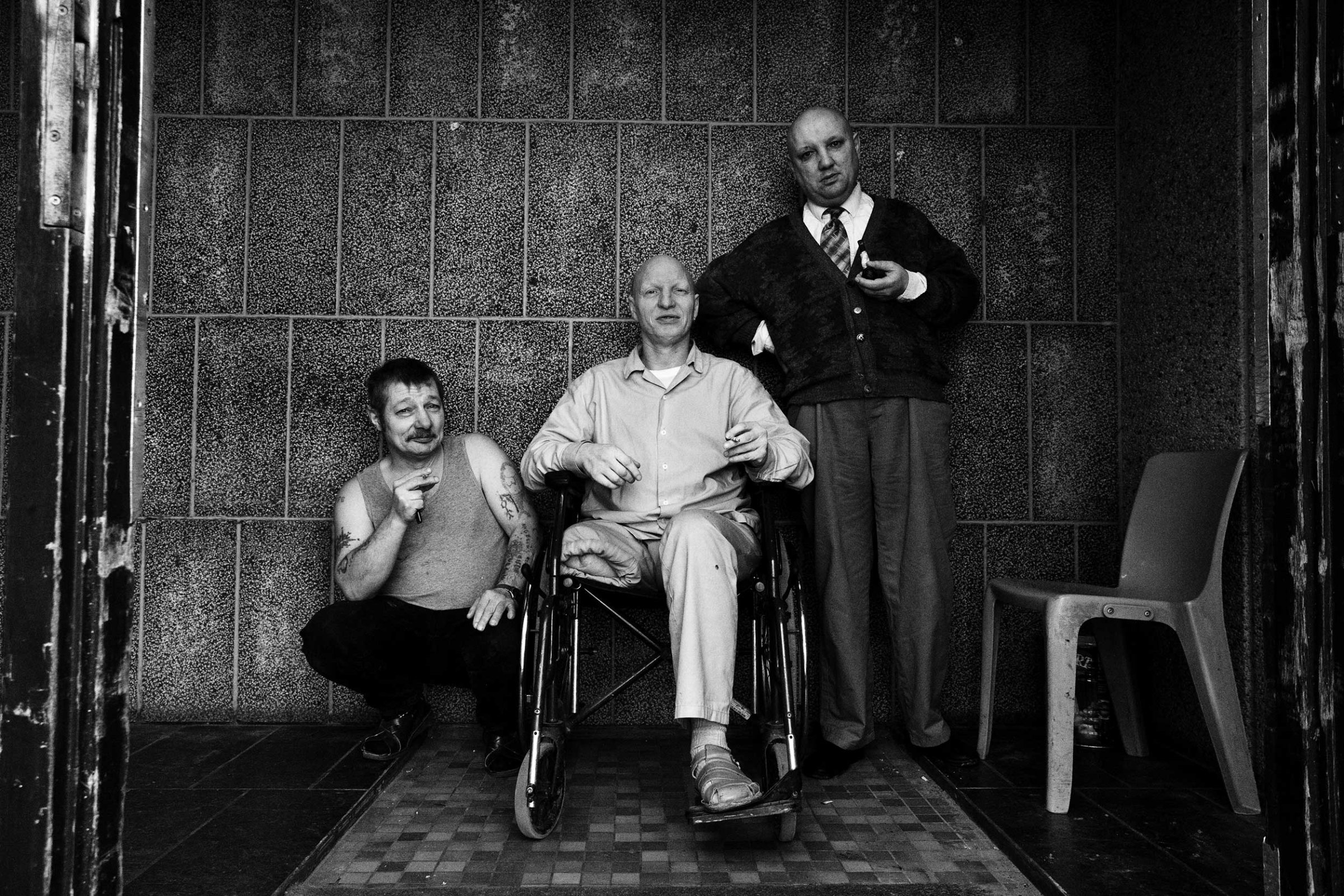

Once inside, Van Malleghem faced yet another hurdle: convincing inmates to let him photograph them. “In the beginning, it’s always a little bit tense,” he explains. “When you get in, people check you out. They try to define you. Are you working for the prison? Are you a psychological resource? What can you bring them? Are you a potential danger?”

All of these questions are asked with a stare. “They don’t say a word. It’s your role to come forward and explain the project, and when they realize that this work will really talk about them and the conditions they’re in, most of them welcome you. It’s like anywhere else: you have to break the ice once or twice, but when they realize that you keep on coming back, the ice has melted.”

At one point, Van Malleghem arranged to spend three days locked up in his own cell, in an attempt to understand how it really felt to be behind bars. “Everything is sanitized, everything is cold. You’re surrounded by grey concrete. It’s all straight lines and straight angles,” he tells TIME. “In fact, you never see something round. You never see curves. Everything is square. Everything is awful.”

For Van Malleghem, this environment is counter-productive to the process of rehabilitation. “I don’t think it helps reform these prisoners. On the contrary, I can understand, if you’re a young detainee, how this experience would foster a form of aggression toward an entire system.”

Sebastien Van Malleghem is a freelance photographer based in Belgium. His first photobook, Police, is available on his website.

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com