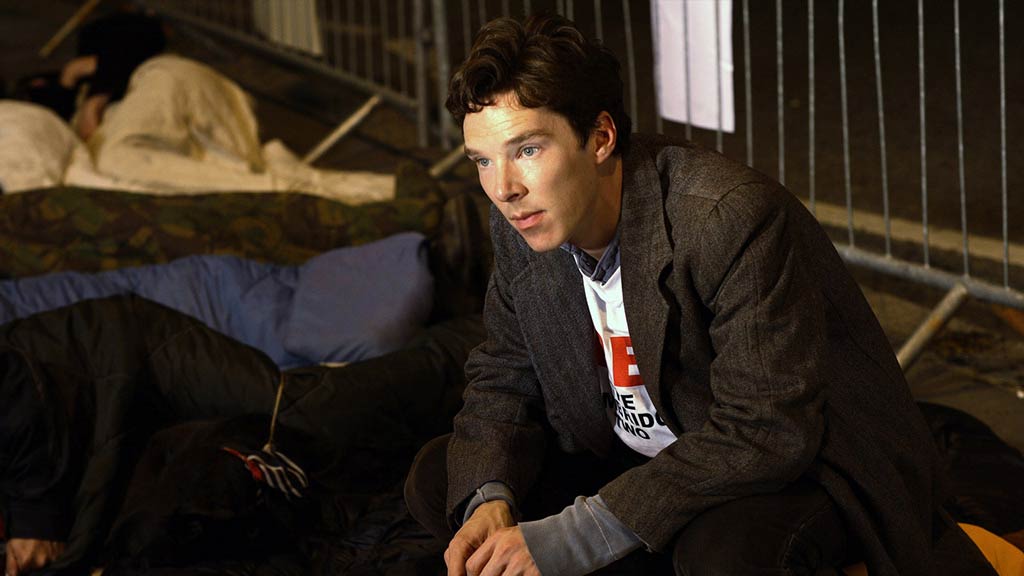

Cumberbatch: It sounds like something you’d find in an eccentric prelate’s vegetable garden. Benedict’s mother Wanda Ventham advised him to choose a moniker less … cumbersome … for his acting career; his father went by the stage name Timothy Carlton. But the young man must have appreciated the curious loftiness of this word, which comes from Old English and loosely means “stream in a valley.” And after all, the name was his. So he found roles suitable for a Benedict Cumberbatch: men above and apart, like Sherlock Holmes in the BBC series, Julian Assange in The Fifth Estate, Stephen Hawking in a TV movie. Fantasy filmmakers recognized his intimidating radiance and cast him as Khan in Star Trek Into Darkness and the Necromancer and Smaug in the Hobbit movies. Soon he will be Marvel’s Sorcerer Supreme, Doctor Strange.

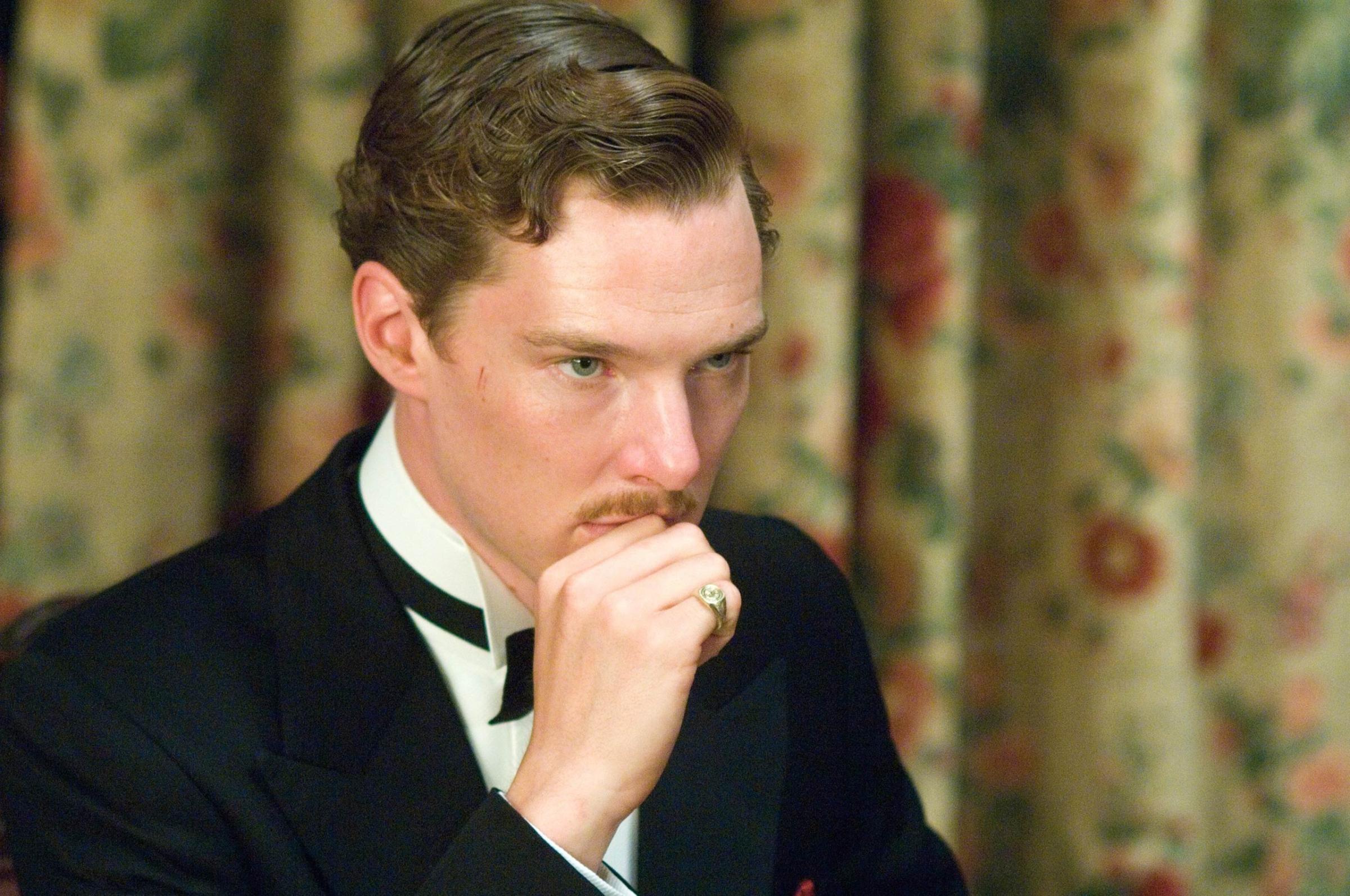

Alan Turing in The Imitation Game may be the actor’s oddest, fullest, most Cumberbatchian character yet. The Cambridge genius who fathered the modern computer, known as the Turing machine–and who presciently asked, “What if only a machine could defeat another machine?”–seems part machine himself. Carrying himself with the hauteur of some creature from an advanced species on its first trip to Earth, he joins the Bletchley Park team charged with breaking the Nazis’ devious Enigma code and airily dismisses the theories of team leader Hugh Alexander (Matthew Goode), while defying the orders of Army Commander Denniston (Charles Dance) by going directly to Winston Churchill. A marathoner as well as a mathematician, Turing is the lonely long-distance runner who intellectually laps his colleagues while insisting on making all the crucial decisions. Why? “Because no one else can.” They are merely clever; he is brilliant. And in wartime, when results trump politesse, brilliance wins.

On its bright face, The Imitation Game, written by Graham Moore and directed by Morten Tyldum, fits into that cozy genre of tortured-genius biopics that sprout like kudzu just in time for the Oscars. But that’s not fair to the film, which outthinks and outplays other examples of the genre (The King’s Speech, The Theory of Everything) just as Turing outraced those around him. For this is a superhero movie of the mind. Unlike the Marvel troupe, whose skills are physical and endlessly watchable, Turing makes magic in his head. The beautiful wheels spin inside; that’s where he flies. And he defeats the villains of unsolvable equations not with a punch but with a keypunch. The “action” here is Turing tinkering with his machine. Or simply thinking–which, as Cumberbatch portrays it, is adventure of the highest order.

The actor doesn’t play Turing so much as inhabit him, bravely and sympathetically but without mediation; that’s your job. He recognizes that this supernal machine had a flaw, or thought it did. Turing’s Achilles heel was his heart, and his shielding his sexuality from his colleagues helps explain his emotional reticence, as the bullying he suffered at school almost justifies the pleasure he takes in being top dog at Bletchley Park. He even proposes marriage to the Enigma team’s one woman, Joan Clarke (Keira Knightley), as a cover for homosexual activities that were illegal in Britain throughout his life, and the penalties for which hastened his death. This superhero is really a tragic hero, doomed not by his “crime” but by society’s ignorant prejudice.

Critics won’t need a Turing machine to pick one of the most smartly judged, truly feeling movies of the year or its most towering, magnetic performance. And though the star’s achievement should be its own reward, he is sure to receive many prizes this Oscar season. He deserves a Cumberbatch of them.

Benedict Cumberbatch Roles You Didn’t Know About

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com