A Russian, a Korean, and a Mexican walk into a bar. How do they communicate?

In English, if at all, even though it’s not anyone’s native language. Swap out a bar for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in China this week, and the attending heads of state from those three countries still have to communicate in English: It’s the only official language of the APEC, even when the APEC gathers in Beijing.

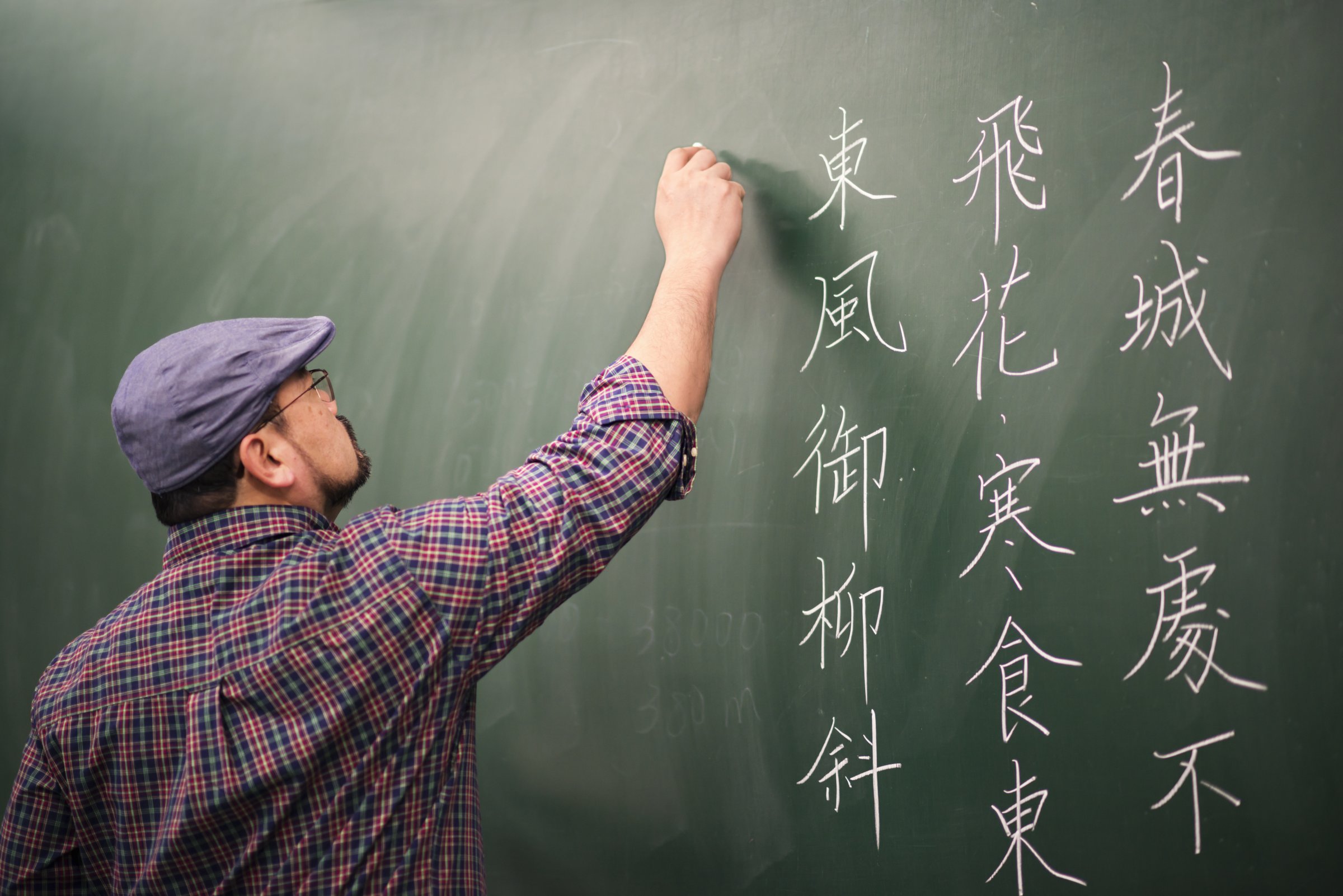

Mark Zuckerberg recently scored points during his own visit to Beijing when he made some remarks in Mandarin. The news sparked talk about whether China’s economic rise means Mandarin could someday rival English as a global language. Don’t count on it. Fluency in Mandarin will always be helpful for foreigners doing business in China, much like mastery of Portuguese will give you a leg up in Brazil. But Mandarin poses no threat to English as the world’s bridge language, the second tongue people turn to when communicating and doing commerce across borders.

Thanks to the British empire, native English speakers are strategically sprinkled across the globe. English is also the native language of shared popular culture – music, movies, even sport, with the recent ascendance of England’s Premier League. And English is undeniably the language of the technologies connecting us all together. Most languages don’t even bother to coin terms for things like “the Internet” or “text” or “hashtag.”

It’s little wonder that an estimated 2 billion people will speak functional English by 2020, the vast majority of them having learned it as their second language.

English is an inherently neutral language: There is no gender in English as there are in Romance languages. There are no class or generational distinctions baked into the language, as there are with so many languages that feature different you’s with different verb conjugations – the deferential you (boss, elder, stranger) versus the familiar you (friend, subordinate, child). Ours is a radically egalitarian and modern language, and it is simpler and more direct as a result.

English is also more politically neutral than we think. Even Islamist Jihadist propagandists would concede that English, is a convenience in spreading their word. And any relative decline over time of America’s global power and influence will actually help, rather than hurt, the cause of English worldwide, further decoupling people’s perception of the language from their perceptions of the United States and its influence.

The French – whose language was the last viable alternative in the race to become the world’s lingua franca – are understandably sore about the triumph of English. But even French companies have had to fall in line, accepting English as their organizational language. In what amounted to a telling parody of modern France, one grievance underlying a recent Air France strike was the airline union’s anger at the adoption of English as the default language for internal communications across its global operations.

The odds against a Chinese dialect ever gaining traction as an international language are formidable, for linguistic, economic, cultural, and political reasons. For starters, the language is just too hard for outsiders to attain fluency. Then there is the inconvenient fact that Mandarin doesn’t hold sway throughout all of China.

Indeed, resistance to any claim the Chinese language may have for global status may be strongest in the country’s own neighborhood, where nations are nervous about China’s intentions. The PEW Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project surveys show that people in nations like the Philippines, Vietnam, Korea, and Japan are far more comfortable with America than with China as regional superpower. And so it’s no accident that English is the only official language of ASEAN, the regional grouping of Southeast Asian nations.

This cordon sanitaire containing China’s cultural (and if it comes to it, military) expansion is one of the lesser appreciated dynamics of today’s world, one that augurs well for the cause of the English language and American cultural influence. All the hype surrounding China’s rise to great power status can make us lose sight of the fact that what realtors might call the “China Adjacent Region” (let’s call it CAR) – the crescent encompassing Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Indonesia, the rest of Southeast Asia, and India – far surpasses China in population and economic power.

So don’t expect Chinese to take on English for global preeminence. That’s the good news for us as Americans. The bad news – at least for Americans thinking they don’t need to learn a second language– is that English’s very universality will make more and more of the world’s population multilingual. If all our kids speak is English, they’ll be at a disadvantage in a globalized labor force – because everyone else will speak it too. But at least we get to pick our second language.

Andres Martinez is editorial director of Zocalo Public Square, for which he writes the Trade Winds column. He teaches journalism at Arizona State University.

Read next: Speaking More Than One Language Could Sharpen Your Brain

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com