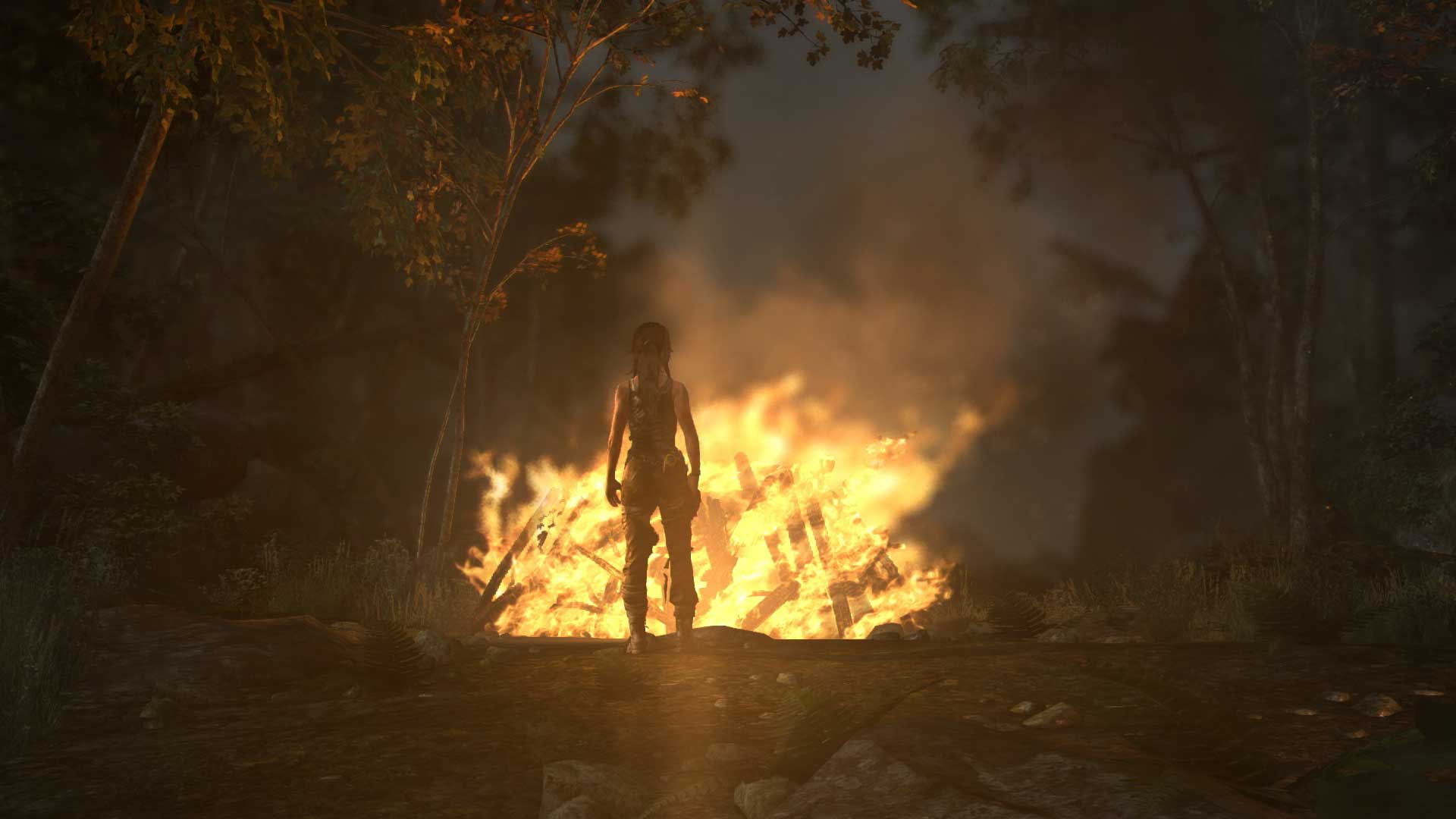

I’m perched on a Notre Dame gargoyle, Batman-like, some 70 meters above a rabble-thronged square. From here I can see the gabled roof of the Palais de Justice and Sainte-Chapelle, the royal church’s spire the next highest object punctuating Paris’s Seine-circled Île de la Cité. Across the river I spy the Louvre, and along the right bank, the Grand Châtelet.

Swiveling 45 degrees, a medieval temple overlooks the 3rd arrondissement. Turning another 45, there’s the Bastille, its broken crenellations like the jags of a giant shattered tooth. The cathedral’s shadow darkens the square below me, where hundreds of tiny figures jostle one another, dangling flaming effigies on poles, chanting, squabbling and occasionally scuffling with the guards, the city alight with hope and terror.

Assassin’s Creed Unity‘s attention to French Revolutionary Parisian detail is remarkable, every landmark and monument built to scale. (It’s also intimately scalable by the player.) Distractions abound: you could spend an hour registering the gothic minutia of a Rayonnant edifice’s tracery, or another enumerating biblical scenes in a church’s stained glass windows. Observe the burnished filigree crowning the massive wrought-iron gates to the Cour du Mai, the Corinthian portico of the triple-domed and frescoed Panthéon, or the sun glinting off lustrous iconography blanketing the dome of Les Invalides. It’s all here, and kind of nuts.

So is Unity a game or interactive diorama? Another tale of secret warring societies supported by its dazzling late 18th century metropolis, or architectonic fetish with a side of pulp?

Maybe both. But then you push a button and leap from your roost and start moving through this ridiculously intricate insurrection simulator, clambering over realistically uneven slate rooftops and corroded chimneys linked by fictional passage-smoothing plank and rope skyways, only to find the actual game sagging beneath the weight of its world design. In short, Unity is a phenomenal world-building achievement held back by a glitchy navigation system.

Moving through the Assassin’s Creed games has always been fidgety, but it’s steadily improved over the years. Unity feels like a step back, though it’s hard to pinpoint why. Perhaps it’s the busier world geometry, its handholds and footpaths multiplied who-knows-how-many-fold, making it even easier to snag on something. Sometimes it’s clearly the game’s impaired frame rate in large crowds lagging behind your input. (That’s not an idle complaint; the game actually stutters severely in spots.) Maybe it’s just buggy. Maybe some of that will be ironed out in future patches. What I do know, is that Arno, the game’s French protagonist–an assassin who’s confused revenge for redemption in the game’s story–sometimes has a mind of his own.

If I push one way, he’ll occasionally leap in another. If I zig, odds are one out of four he’ll zag. I expect some slack in any 360-degree motion system, but this is something else. I haven’t fought the controls like this since the original Assassin’s Creed. It’s harmless enough when you’re wall-crawling freeform, but under the gun, say in one of those target-tailing missions with bonus challenges like “don’t touch the water,” whiffing the mission because Arno decides to dive off a wooden post into the drink instead of leaping to the next one on the third or fourth replay is exasperating.

But the biggest problem is that sometimes Arno won’t do anything at all.

Climb a building with clearly navigable points and sometimes Arno gets stuck. Not “That next thing’s too high up, find another way” stymied, but “Why am I halfway up this continuous lattice and hitting all the right buttons and he’s frozen stiff?” I’m not misreading the path, because if I hammer the buttons or reset the thumbstick, he’ll swing into action and clear the distance, no problem. And I ran into this in even the simplest scenarios: dangling from a rope between buildings or hanging from the edge of an unobstructed platform (he’d neither climb nor drop), or trying to dive Dukes of Hazard style through an open window (hammering the button the game keeps telling me to hammer while ignoring my input). This is next-gen parkour?

It’s a shame, because so much else about Unity‘s design overhaul works. The new 3D overview map helps you better pinpoint objects in a 3D world. A downward free-run option (hold a button to climb down automatically) makes descending from even the highest points quick and safe. And Eagle Vision, the game’s spot-the-bad-guys radar system, now only works for brief periods, encouraging more judicious use.

There’s even a modest roleplaying angle: weapons, clothing, stealth moves and combat abilities–most familiar with a few wrinkles–are now spending-based unlocks that let you finesse your play style meaningfully. One of those skills, lockpicking, finally strikes the right balance between twitchy and skillful and now applies to doors that can open up alternate routes in missions. Those missions now feel like proper assassination puzzles, the game dropping you outside heavily patrolled fortresses and folding in optional goals you can engage to tweak your infiltration routes or unlock distractions. Carried over to the new cooperative play modes, where you and up to three other players can work together to dispatch operatives or recover loot, and Unity surpasses its predecessors.

Some of the improvements are simple subtractions: The removal of automatic counters revitalizes combat, which regains some the original’s brutal simplicity and timing-related volatility. Guards on alert can no longer be assassinated from hiding spots (like hay wagons), encouraging shrewder stealth tactics. The home improvement game has fewer spending tiers and ties this more to side missions like the frontier activities in Assassin’s Creed III. And assassin-recruiting, training and deploying is no more, eliminating a pseudo-strategic moneymaking layer I never particularly liked.

Other changes seem like half-measures or outright missteps. Adding a button that lets you crouch gives you more approach options (to say nothing of making you feel stealthier), but the new guard-luring gimmicks–cherry bombs or taunting guards to probe by letting yourself be spotted then breaking the sightline–often fail because the guards seem to know you’re waiting and stop short of your hiding spot, even as you absurdly pepper them with fireworks.

While combat is more gratifying and enemies more aggressive, your bag of tricks remains small and the opponent A.I. types still too undifferentiated. (I powered through the game using the same attack-parry-stun-attack combos.) The new press-a-button-to-stick cover system often disregards your input and can’t be depended on during hair-trigger maneuvers. And what passes for a future story about leaping between servers and playing through alternate timelines to avoid detection (the series is basically The Matrix meets Ken Follett) recalls the dreary “Desmond climbs” missions in Assassin’s Creed III, where you prosaically pushed the thumbstick in the direction you wanted to travel and watched stuff happen.

Speaking of the story, Ubisoft was wise to make it about Arno and keep most of the Revolution’s politicking in the background, but the character as written barely connects. Whatever we’re meant to feel about the things he endures, whatever the writers intended beyond a bit of brooding, debauchery and sense of being dragged along by tidal forces, Arno’s a little boring, his arc more an undifferentiated slope. His romantic interest has far more brio, and makes you wonder what might have been, had you been able to explore her story instead.

Shall I bother to malign the ending? Have endings in these games ever delivered? Here it’s another anticlimactic, predictable and tediously difficult mess, where–minor spoiler warning–you’re essentially dueling with Emperor Palpatine (think about what Palpatine’s known for), making use of none of the things you’ve just spent the entire game learning to do, while he chants “I have you now!” (Yes, that’s verbatim.)

“The past is not lost, the past lives inside us,” says a narrator during the game’s intro. It’s supposed to be a reference to the game’s parapsychological conceit about genetic memory, not ironic commentary on the game design. Unity has plenty of moments where some of its re-grounded systems harmonize, but too many where they don’t. Historical flavor and architectural verisimilitude alone can’t carry a game, and may in fact be part of what works against this one, even as I’ll admit to being gobsmacked at the audacity of Ubisoft’s city-replicating exercise, a towering achievement unto itself.

3 out of 5

Review using the PlayStation 4 version of the game.

See The 15 Best Video Game Graphics of 2014

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Write to Matt Peckham at matt.peckham@time.com