When Larry Sultan died somewhat suddenly in 2009 at the age of 63, over 400 people attended his public memorial service. The majority of them were former students, who came in droves; Sultan had taught in Bay Area institutions for over three decades. His impact − as an artist and educator − was immeasurable. One person after another spoke that evening about the way in which Sultan had challenged their stake in the world, not only as artists but also as thinking, feeling human beings. “What a massive task this is,” said his former pupil Jon Rubin in his eulogy. “How many hundreds of students has he deeply affected? How can we, or I, account for his influence? What a remarkable and fortunate group of people we are.” Rubin was right: Sultan’s absence left a devastating, impossible void, but it also reminded those he left behind of what a terrific force he had been.

Five years later, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is holding Sultan’s first posthumous retrospective, called Here and Home. The exhibition consists of six substantial bodies of work made between 1975 and 2009. They may, at first glance, appear disparate. Swimmers legs entwine underwater in one series; Sultan’s parents appear in a retirement community in another; appropriated black-and-white images of enigmatic scenes in a third. But look closer. Each blends the tools of documentary and staged photography. Each probes desire and fantasy in relation to domestic life. Each examines emotional and physical displacement.

Larry Sultan was himself displaced, in a way. Born in Brooklyn, New York in 1946 to Jewish parents, he moved to the San Fernando Valley − just outside of Los Angeles, where his father got a job with Schick razors − as a child. It was a shift that would inform his life’s work. Despite settling in the Bay Area in his 20s, the suburban landscape, and its cultural implications, are threaded throughout Sultan’s photographic legacy.

The place to begin with Sultan’s work is Evidence (1977), which was conceived of as a book and exhibition along with his long-time collaborator, the artist Mike Mandel. To make the project, the duo combed through two million governmental and corporate archival photographs, ultimately settling on 59. The images − strange, dream-like, and sometimes-violent − were displayed with no accompanying caption or explanation. They depict an anonymous man hooked up to a sea of wires, a rope being held out like a noose by a gloved hand, and construction workers wading through a sea of heavy foam, among other things. Divorced from context, each photograph takes on a new, convoluted visual poetry, challenging how “documentary” photography can and should function. (This strategy of appropriating and dissociating images has since exploded with the Internet age, making it hard to remember a time in which this idea was novel and risky.)

Also featured in the exhibition are images from his book Pictures From Home (1992), an ambitious project that Sultan worked on for nearly a decade. It is, in some sense, an aggregate of mini-collections: Sultan’s aging parents, stills from old home movies, transcribed interviews with his parents, and family snapshots appear side by side, creating a quiet but profoundly stirring portrait of familial intimacy. Sultan ricochets between past and present, weaving together a portrait of his nuclear family that engages conditions of class, memory, and physical and emotional distance. There are countless artists who have made work on the subject of their own family lives and yet I am pressed to think of another who has done it in such a brilliant and sensitive way.

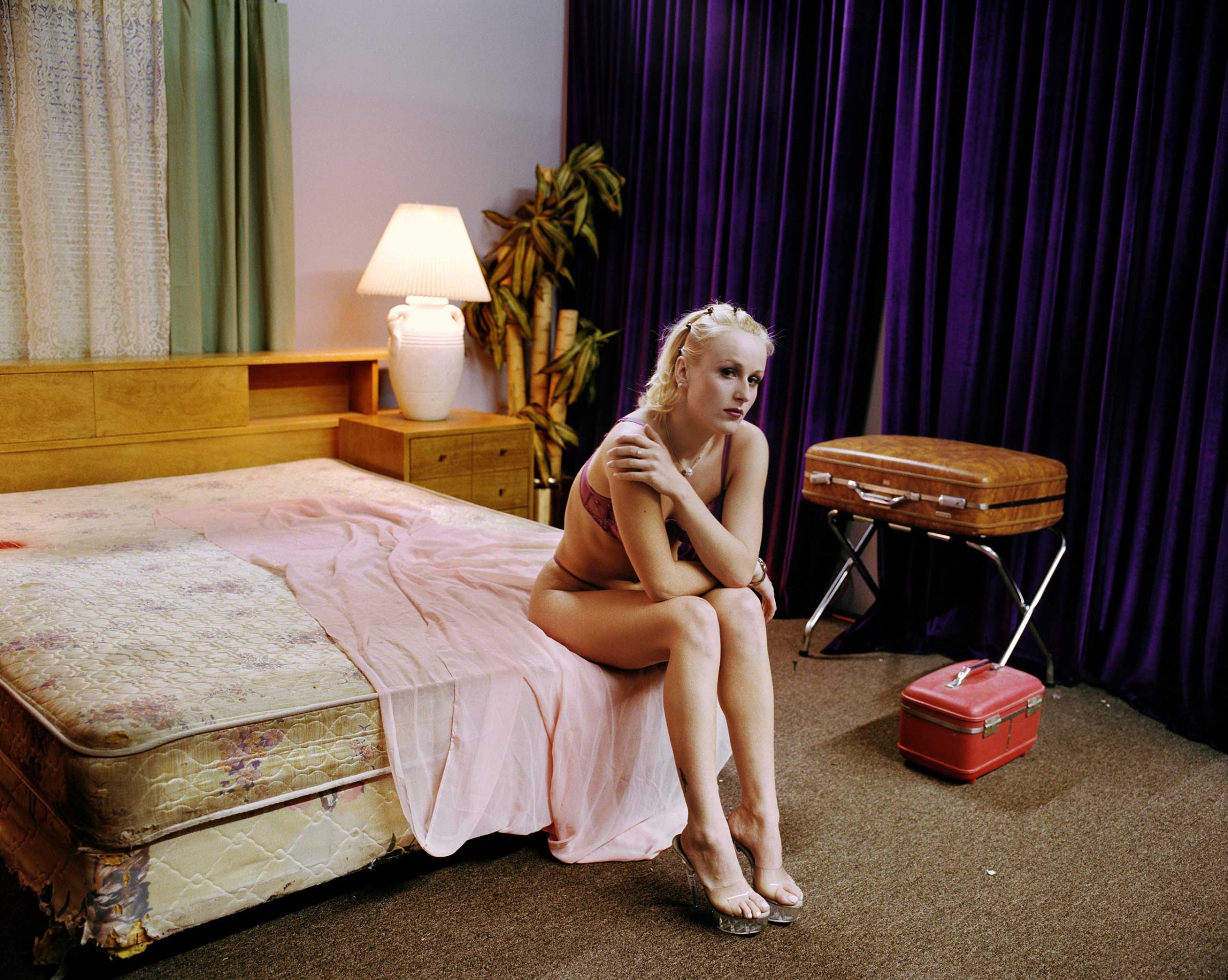

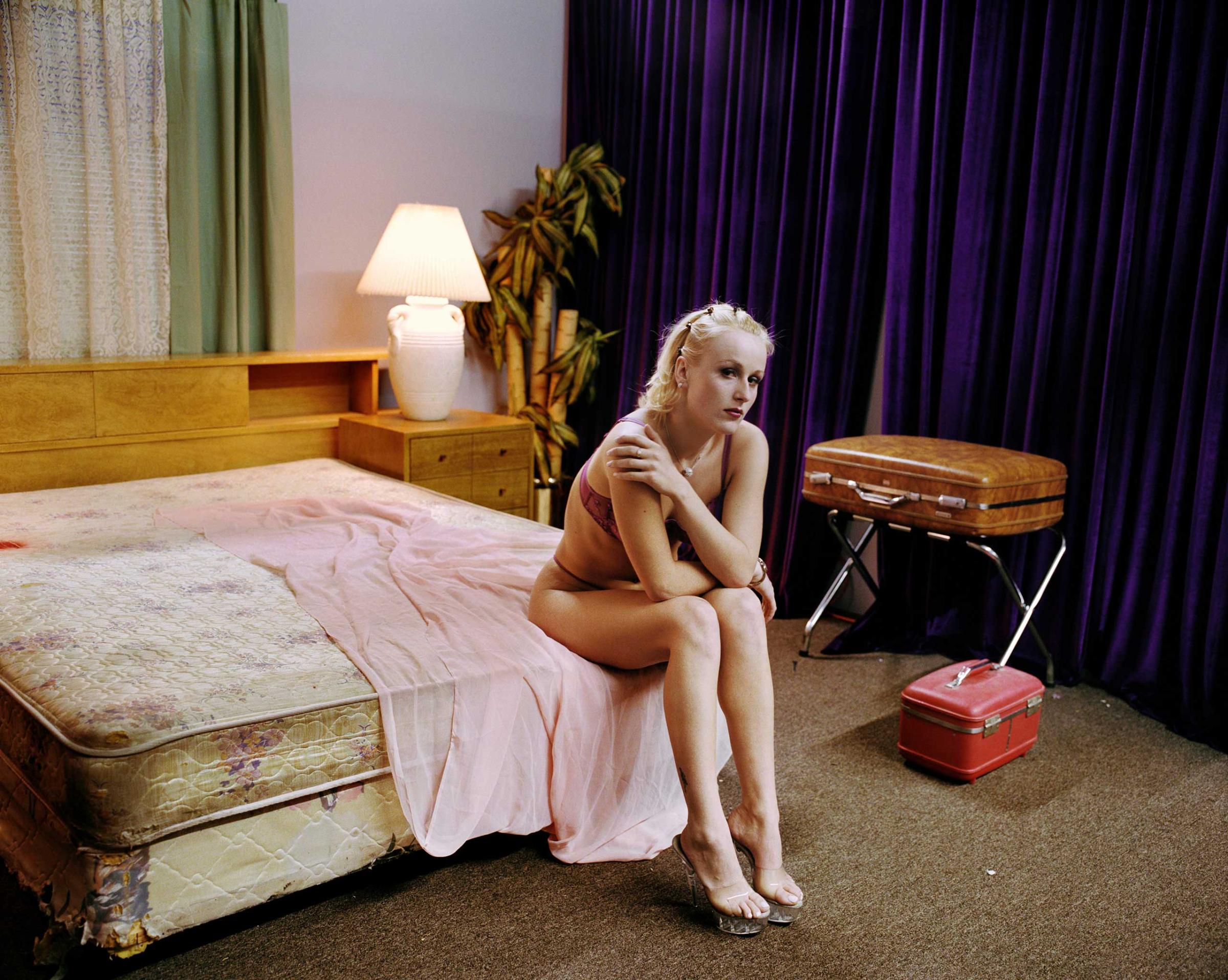

One of Sultan’s next projects, The Valley (2000) is, in some predictable and unpredictable ways, a logical extension of Pictures From Home. The titular valley in question is the San Fernando Valley, an area that has become home to one of the largest pornographic industries in the world. The first pictures in the series were taken on a one-day editorial assignment, in which Sultan photographed an adult film star at work. Sultan was so fascinated by the setting (domestic spaces nearly identical to those he grew up in) and the action (the staged performance of desire), that he continued the project for two more years. He photographed everything around the action, rather than the sex itself: actors and actresses lounging before and after shooting, interior facades, light stands, and dogs on set. The performance itself is referred to only in oblique shadows and partial limbs. Sultan is careful not to re-create the pornographic experience, even through a critical distance. Rather, and much like in Pictures From Home, Sultan utilizes the domestic construct to examine the space between fantasy and reality.

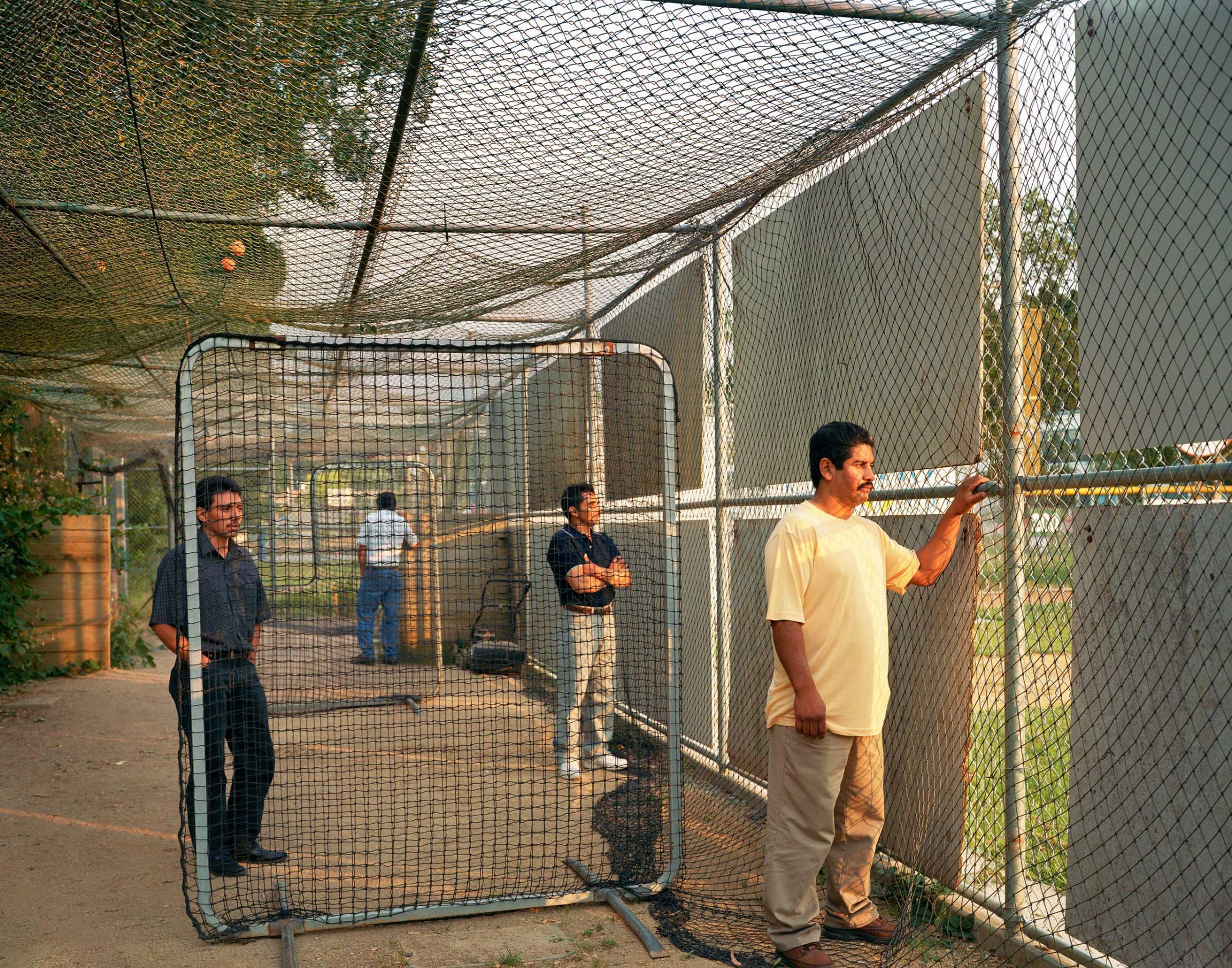

Homeland (2009) is Sultan’s final body of work. And perhaps fittingly so: the large prints, which picture Hispanic day laborers posed in California landscapes on the cusp of suburban tract homes, are his most somber and romantic work. Sultan drew from his own memories to pose the men, who string lights on a tree, row a boat in the river, and carry food in dishes. The activities are mundane; the images are lush and spectacular. They are a kind of grand finale, touching on each of Sultan’s lifelong interests: domestic ritual, suburban landscape and displaced personhood.

Sultan’s images are, as he was, at once sincere and seductive, guarded and vulnerable. He was ultimately interested in our lifelong search for placement, picturing people who lost their homes (immigrants in foreign landscapes), changed their lifestyles (his own parents in their newfound retirement community), or staged domestic scenes (porn stars). Even his early work, Evidence, was about making images homeless by exiling them from their contexts.

His sensibility has informed the generations that followed; if only he could be here to see it.

Carmen Winant is an artist, writer and assistant professor of visual studies and contemporary art history at CCAD.

Larry Sultan was a photographer and professor based in the San Francisco Bay Area. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art retrospective Here and Home opens on Nov. 9, 2014 and runs until March 22, 2015.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com