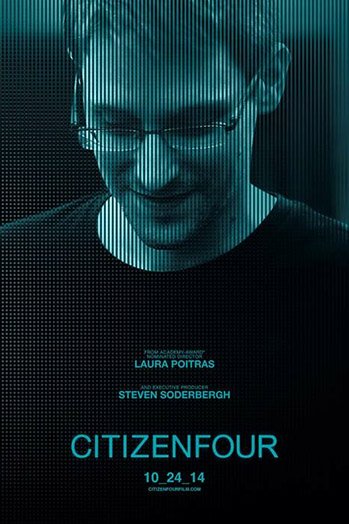

In December 2012, a mysterious person known only as Citizenfour contacted documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras with promises of important revelations about the U.S. government’s spy apparatus. Before they met, Citizenfour sent her this warning: “For now, know that every border you cross, every purchase you make, every call you dial, every cell-phone tower you pass, friend you keep, site you visit and subject line you type is in the hands of a system whose reach is unlimited but whose safeguards are not.”

As Edward Snowden typed that email, was he humming the 1983 Police song “Every Breath You Take” and transposing Sting’s threat of an ex-lover’s surveillance to the National Security Agency? (“Every single day/ Every word you say/ Every game you play, every night you stay/ I’ll be watching you.”) Snowden, an IT analyst under contract with the consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton, had downloaded thousands of NSA documents to present to journalists he could trust to sift through the material and publish what was pertinent. This included Poitras and political gadfly Glenn Greenwald, with Greenwald’s Guardian colleague Ewen MacAskill soon joining them in a Hong Kong hotel room.

The news stories from this cache stash revealed a program monitoring the phone calls and social media of U.S. citizens, and earned the 30-year-old Snowden runner-up status as TIME’s Person of the Year for 2013. (He lost to the Pope, who gets his inside information from an even higher source.) For his service, the U.S. government charged Snowden with espionage, invalidated his passport and stranded him in Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport for 5½ weeks, before he found temporary asylum in Russia, because no other country would challenge U.S. pressure and accept him as a political refugee. Snowden must believe that, for the rest of his days abroad, they’ll be watching him.

Moviegoers will too, through Hollywood’s lens. Oliver Stone is preparing The Snowden Files, possibly starring Joseph Gordon-Levitt and based on a biography by the Guardian‘s Luke Harding (which Greenwald called “a bullshit book” because Harding didn’t speak to Snowden). Sony Pictures has an option to make a movie of Greenwald’s No Place to Hide.

But for the pure, driven Snowden, you must see Citizenfour, an inside view from a filmmaker who is also familiar with government pressure in the Land of the Free: for her 2006 doc My Country, My Country, about a Sunni physician and democracy advocate in U.S.-occupied Iraq, Poitras earned a spot on the Department of Homeland Security’s “watch list.” (Every breath you take, every call you make …) Focusing on the eight days in June 2013 when Snowden first spilled his and his computer’s guts to the three journalists in his 10th-floor room at the Mira Hotel, this is a fascinating, edifying and creepy record of history in the making.

Why Citizenfour? Here’s a wild guess: Snowden sees himself as the latest American — following Daniel Ellsberg with the Pentagon Papers, William Binney for his 2002 NSA whistle-blowing and Bradley (now Chelsea) Manning with the WikiLeaks documents — to risk his liberty by revealing U.S. government secrets. (Ellsberg, like Snowden, was charged under the 1917 Espionage Act, before being acquitted. Manning, accused of “aiding the enemy,” was convicted in a military court of 17 other charges and is serving a 35-year sentence at Leavenworth. Binney, the subject of Poitras’ short film The Program, never did time, but in 2007 armed agents broke into his home and confiscated his computer and business papers.)

Snowden wasn’t a Harvard-educated Beltway insider like Ellsberg, a 30-year NSA veteran like Binney or a soldier like Manning. Getting his high school diploma through a GED and doing a brief spell at a Maryland community college, he impressed employers with his intelligence and his command of encryption. That secured him jobs in the government and eventually a spot as a Booz Allen contractor. Quiet but not a loner, he has a longtime girlfriend, Lindsay Mills, who lived with him in Hawaii and eventually joined him in Moscow. He is a vegetarian who sometimes eats pepperoni pizza, because who doesn’t love pepperoni pizza?

In Poitras’ closeup view, Snowden is a pretty impressive specimen of the genus Nerdus. He speaks in long, fluent sentences, and his tone is serious with occasional flecks of humor. He correctly anticipates what’s in store for him and makes clear that the need for the public to know the range of government eavesdropping is worth the price he will pay. He radiates an almost Zen equilibrium; on one application form he listed Buddhist as his religion because agnostic wasn’t one of the choices. He keeps saying, “I’m not the story,” in the hope that the impact of the revelations he’s providing will distract the media from putting a face, his face, on the news.

He must have known that that wouldn’t happen. For all his calm, Snowden pursues the meticulous safeguards of a hunted man in a John le Carré spy thriller. He devises elaborate codes for meeting Poitras — “I’ll be playing with a Rubik’s Cube” — and when fire-drill bells ring unexpectedly in his room, he gets so jittery that Greenwald says, “You’ve been infected by the paranoia bug.” Snowden covers himself with a sheet while typing a certain password on his laptop; he calls it “my mantle of power,” alluding to the World of Warcraft video games. He also alerts Poitras to the enormous reach, or perhaps simply the enormity, of the U.S. snoop system, telling her, “Your adversary is capable of 1 trillion queries per second.” It’s fruitless to try outracing the NSA megacomputers; the only option may be exposing what’s inside them.

Poitras’ movie works even better as a horror picture — perfect for Halloween week. (Even the title suggests a scare-film franchise: After Insidious 2 and Saw 3 comes Citizenfour.) The heroine of the new movie Ouija, who communicates with the dead through a Hasbro toy, can’t compete with Snowden. His Ouija board is his computer; it helps him access what he sees as the U.S.’s darkest real-life secrets. His hotel room is well lighted, but for eight days he’s trapped in it, like Cary Elwes in the Saw basement, with people he has to hope are on his side. The camera glare gives a ghostly pallor to the young man, who had spent his last few months in sunny Hawaii. He could be a specter reaching out from the other side to warn the living. When he picks up his hotel phone and tells the operator, “There’s no Edward Snowden here,” you almost believe him.

Now for the obligatory George Packer paragraphs. The New Yorker staff writer, in his Oct. 20 story based on his visit with Poitras as she completed the editing of her film in Berlin, criticized her for not taking a more skeptical view of her subject. Packer quoted Binney, a vocal supporter of Snowden and a prominent supporting voice in Citizenfour, as saying in USA Today that when Snowden went beyond leaking information about the NSA’s spying in the U.S. to revealing the agency’s spy strategies against China, he was “transitioning from whistle-blower to traitor.” Packer wrote, “This is a distinction that Poitras might have induced Binney to pursue.”

A Binney follow-up on this allegation would have been welcome, since elsewhere in the interview he lavishly praised Snowden’s efforts. But Packer can’t deny Poitras’ openness to potentially hostile journalists — i.e., him. Last year he wrote a piece for Prospectus called “The Errors of Edward Snowden and Glenn Greenwald” (and got his own assertions picked apart by Henry Farrell in “George Packer and His Problems”). Yet Poitras agreed to talk to Packer, who apparently never raised the question about Binney. That is a question he might have induced her to answer.

To state the obvious: Poitras didn’t intend her movie as a balancing act of pro- and anti-Snowden opinions — if any film or TV documentary has ever taken the impartial Olympian overview that Packer demands. Citizenfour is, at heart, a portrait of a man at the moment he chooses to change Americans’ understanding of what their government knows about them. And it ends with the hint of another lone wolf ready to spill more essential dirt. Greenwald doesn’t speak to Snowden of the new whistle-blower; he writes some information on papers he then tears into pieces. On one of the scraps we glimpse the word POTUS: President of the United States. Snowden sees this and whispers, “Holy shit.”

Stay tuned for Citizenfive.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com