You are getting a free preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. This story was originally published in the June 14, 1999 issue of TIME. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. Want access to more subscriber-only content, click here to subscribe.

Oliver Wendell Holmes once observed that every profession is great that is greatly pursued. Boxing in the early ’60s, largely controlled by the Mob, was in a moribund state until Muhammad Ali–Cassius Clay, in those days–appeared on the scene. “Just when the sweet science appears to lie like a painted ship upon a painted ocean,” wrote A.J. Liebling, “a new Hero…comes along like a Moran tug to pull it out of the ocean.”

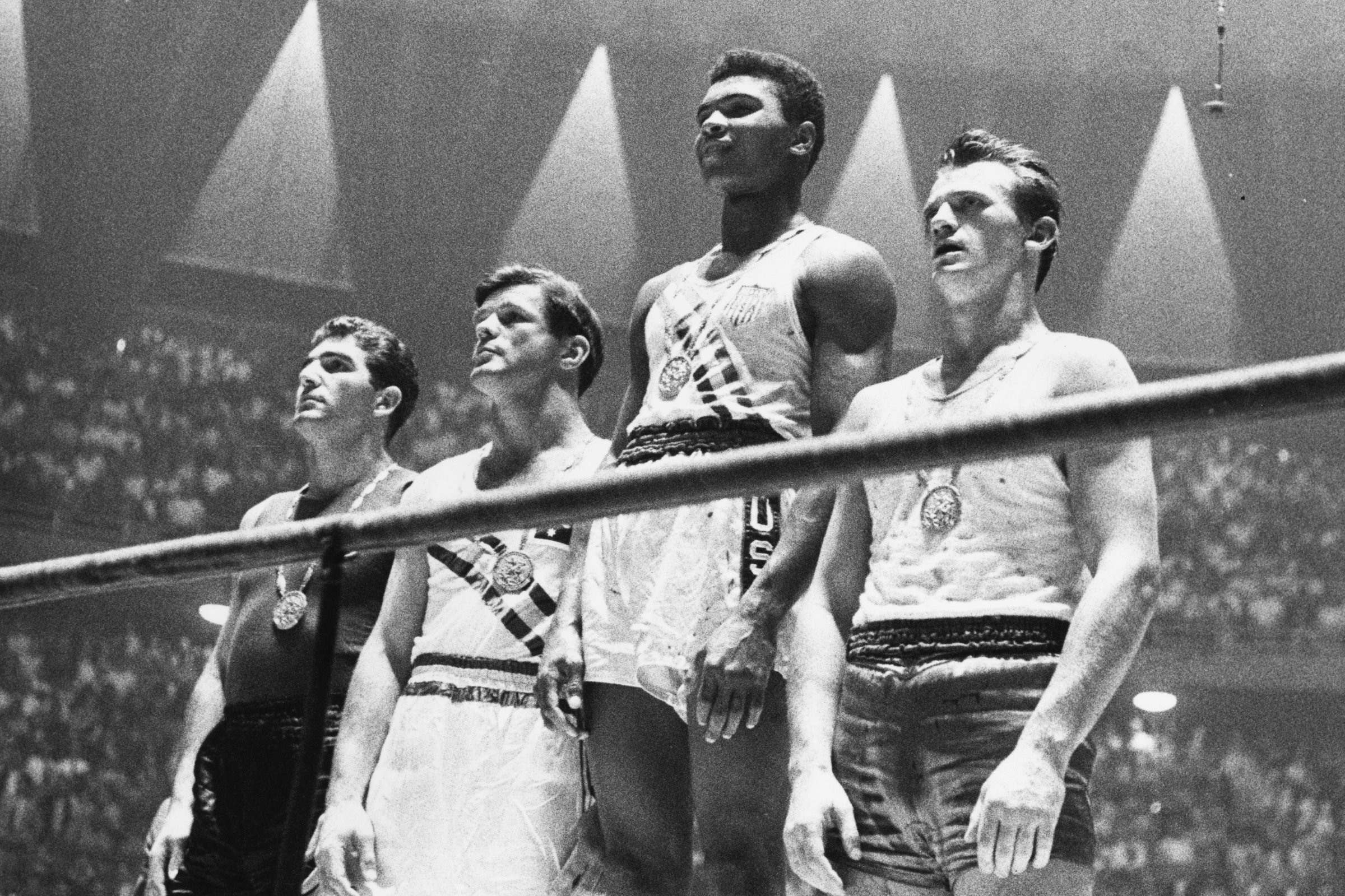

Though Ali won the gold medal at the Rome Olympics in 1960, at the time the experts didn’t think much of his boxing skills. His head, eyes wide, seemed to float above the action. Rather than slip a punch, the traditional defensive move, it was his habit to sway back, bending at the waist–a tactic that appalled the experts. Lunacy.

Nor did they approve of his personal behavior: the self-promotions (“I am the greatest!”), his affiliation with the Muslims and giving up his “slave name” for Muhammad Ali (“I don’t have to be what you want me to be; I’m free to be what I want”), the poetry (his ability to compose rhymes on the run could very well qualify him as the first rapper) or the quips (“If Ali says a mosquito can pull a plow, don’t ask how. Hitch him up!”). At the press conferences, the reporters were sullen. Ali would turn on them. “Why ain’t you taking notice?” or “Why ain’t you laughing?”

It was odd that they weren’t. He was an engaging combination of sass and sweetness and naivete. His girlfriend disclosed that the first time he was kissed, he fainted. Merriment always seemed to be bubbling just below the surface, even when the topics were somber. When reporters asked about his affiliation with Islam, he joked that he was going to have four wives: one to shine his shoes, one to feed him grapes, one to rub oil on his muscles and one named Peaches. In his boyhood he was ever the prankster and the practical joker. His idea of fun was to frighten his parents–putting a sheet over his head and jumping out at them from a closet, or tying a string to a bedroom curtain and making it move after his parents had gone to bed.

The public as well had a hard time accepting him. His fight for the heavyweight championship in Miami against Sonny Liston was sparsely attended. Indeed, public sentiment was for Liston, a Mob-controlled thug, to take care of the lippy upstart. Liston concurred, saying he was going to put his fist so far down his opponent’s throat, he was going to have trouble removing it.

Then, of course, three years after Ali defended the championship, there came the public vilification for his refusal to join the Army during the Vietnam War–“I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong”–one of the more telling remarks of the era. The government prosecuted him for draft dodging, and the boxing commissions took away his license. He was idle for 3 1/2 years at the peak of his career. In 1971 the Supreme Court ruled that the government had acted improperly. But Ali bore the commissions no ill will. There were no lawsuits to get his title back through the courts. No need, he said, to punish them for doing what they thought was right. Quite properly, in his mind, he won back the title in the ring, knocking out George Foreman in the eighth round of their fight in Zaire–the “Rumble in the Jungle.”

Ali was asked on a television show what he would have done with his life, given a choice. After an awkward pause–a rare thing, indeed–he admitted he couldn’t think of anything other than boxing. That is all he had ever wanted or wished for. He couldn’t imagine anything else. He defended boxing as a sport: “You don’t have to be hit in boxing. People don’t understand that.”

He was wrong. Joe Frazier, speaking of their fight, said he had hit Ali with punches that would have brought down a building. Coaxed into fights by his managers long after he should have retired, and perhaps because he loved the sport too much to leave it, Ali ended up being punished by the likes of Leon Spinks and Larry Holmes, who took little pleasure in what they were doing.

Oscar Wilde once suggested that you kill the thing you love. In Ali’s case, it was the reverse: what he loved, in a sense, killed him. The man who was the most loquacious of athletes (“I am the onliest of boxing’s poet laureates”) now says almost nothing: he moves slowly through the crowds and signs autographs. He has probably signed more autographs than any other athlete ever, living or dead. It is his principal activity at home, working at his desk. He was once denied an autograph by his idol, Sugar Ray Robinson (“Hello, kid, how ya doin’? I ain’t got time”), and vowed he would never turn anyone down. The volume of mail is enormous.

The ceremonial leave-taking of great athletes can impart indelible memories, even if one remembers them from the scratchy newsreels of time–Babe Ruth with the doffed cap at home plate, Lou Gehrig’s voice echoing in the vast hollows of Yankee Stadium. Muhammad Ali’s was not exactly a leave-taking, but it may have seemed so to the estimated 3 billion or so television viewers who saw him open the Atlanta Olympics in 1996. Outfitted in a white gym suit that eerily made him seem to glisten against a dark night sky, he approached the unlit saucer with his flaming torch, his free arm trembling visibly from the effects of Parkinson’s.

It was a kind of epiphany that those who watched realized how much they missed him and how much he had contributed to the world of sport. Students of boxing will pore over the trio of Ali-Frazier fights, which rank among the greatest in fistic history, as one might read three acts of a great drama. They would remember the shenanigans, the Ali Shuffle, the Rope-a-Dope, the fact that Ali had brought beauty and grace to the most uncompromising of sports. And they would marvel that through the wonderful excesses of skill and character, he had become the most famous athlete, indeed, the best-known personage in the world.

George Plimpton was the founding editor of the Paris Review and the author of Truman Capote.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com