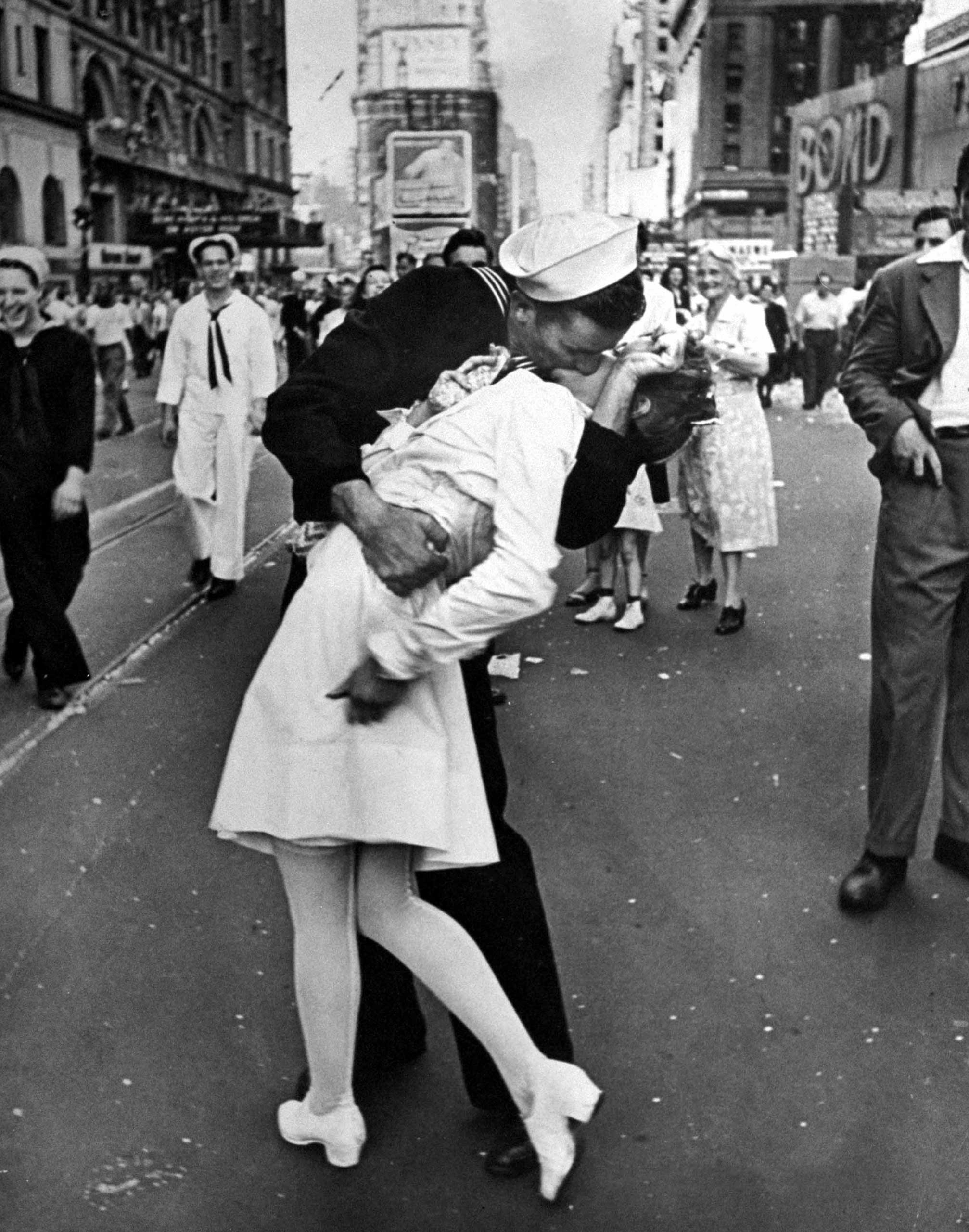

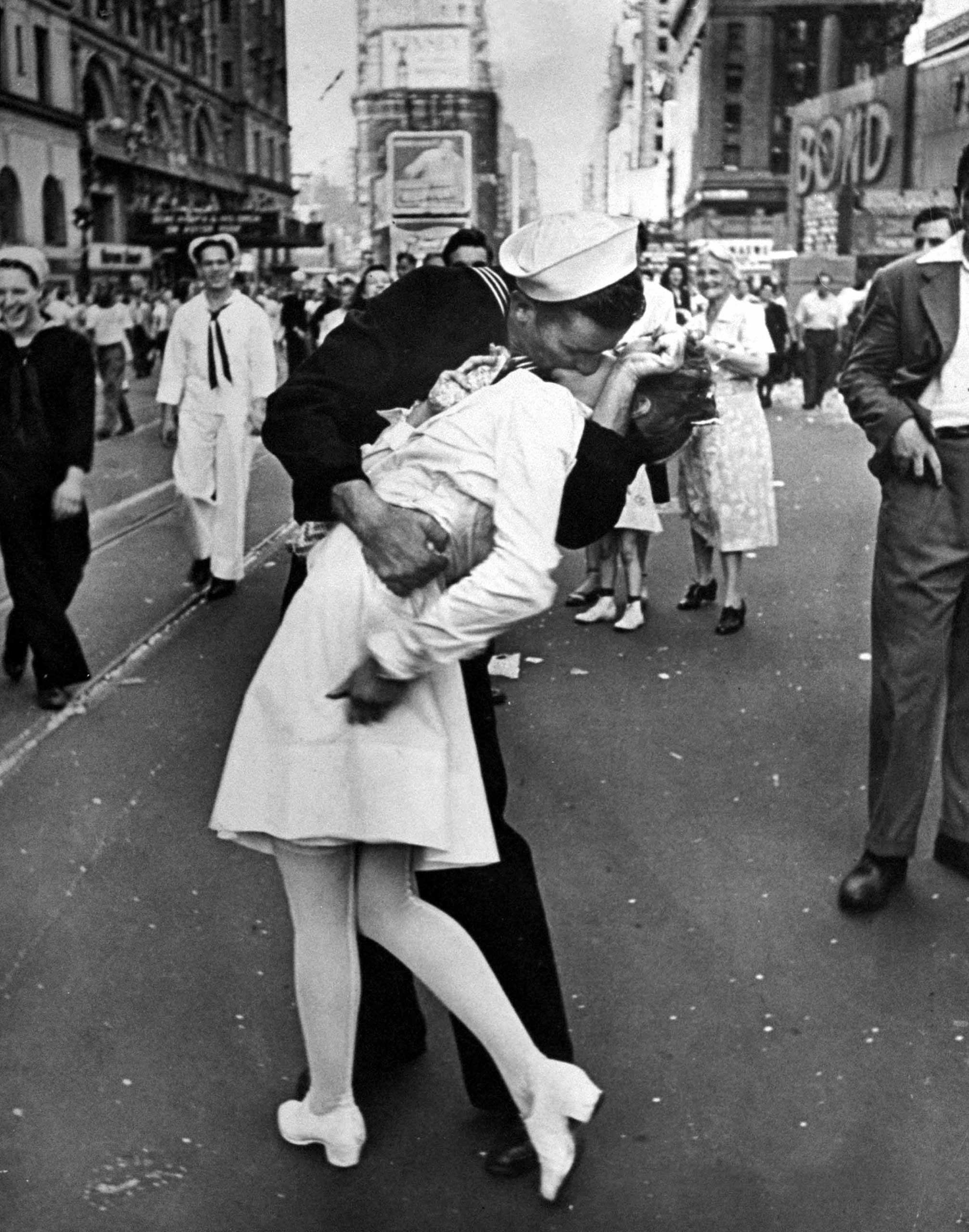

Made almost 70 years ago, it remains one of the most famous photographs—perhaps the most famous photograph—of the 20th century: a sailor kissing a nurse in Times Square on V-J Day in August 1945.

That simple, straightforward description of the scene, however, hardly begins to capture not only the spontaneity, energy and exuberance shining from Alfred Eisentaedt’s photograph, but the significance of the picture as a kind of cultural artifact. “V-J Day in Times Square” is not merely the one image that captures what it felt like in America when it was announced, after a half-decade of conflict, that Japan had surrendered and that the War in the Pacific—and thus the Second World War itself—was finally over. Instead, for countless people, Eisentaedt’s photograph captures at least part of what the people experience when war, any war, is ended.

(It’s worth noting that many people view the photo as little more than the documentation of a very public sexual assault, and not something to be celebrated.)

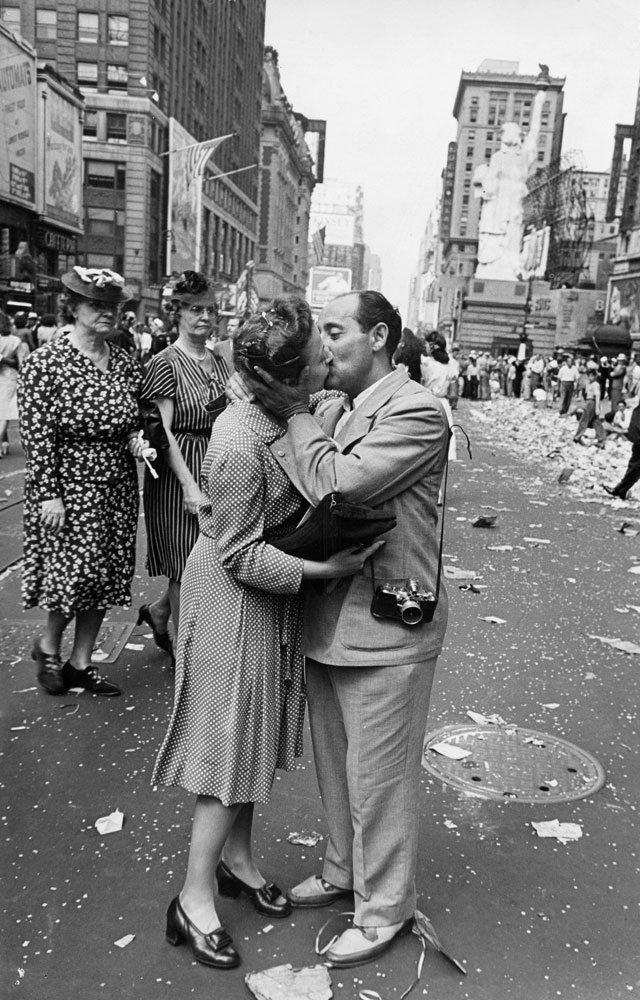

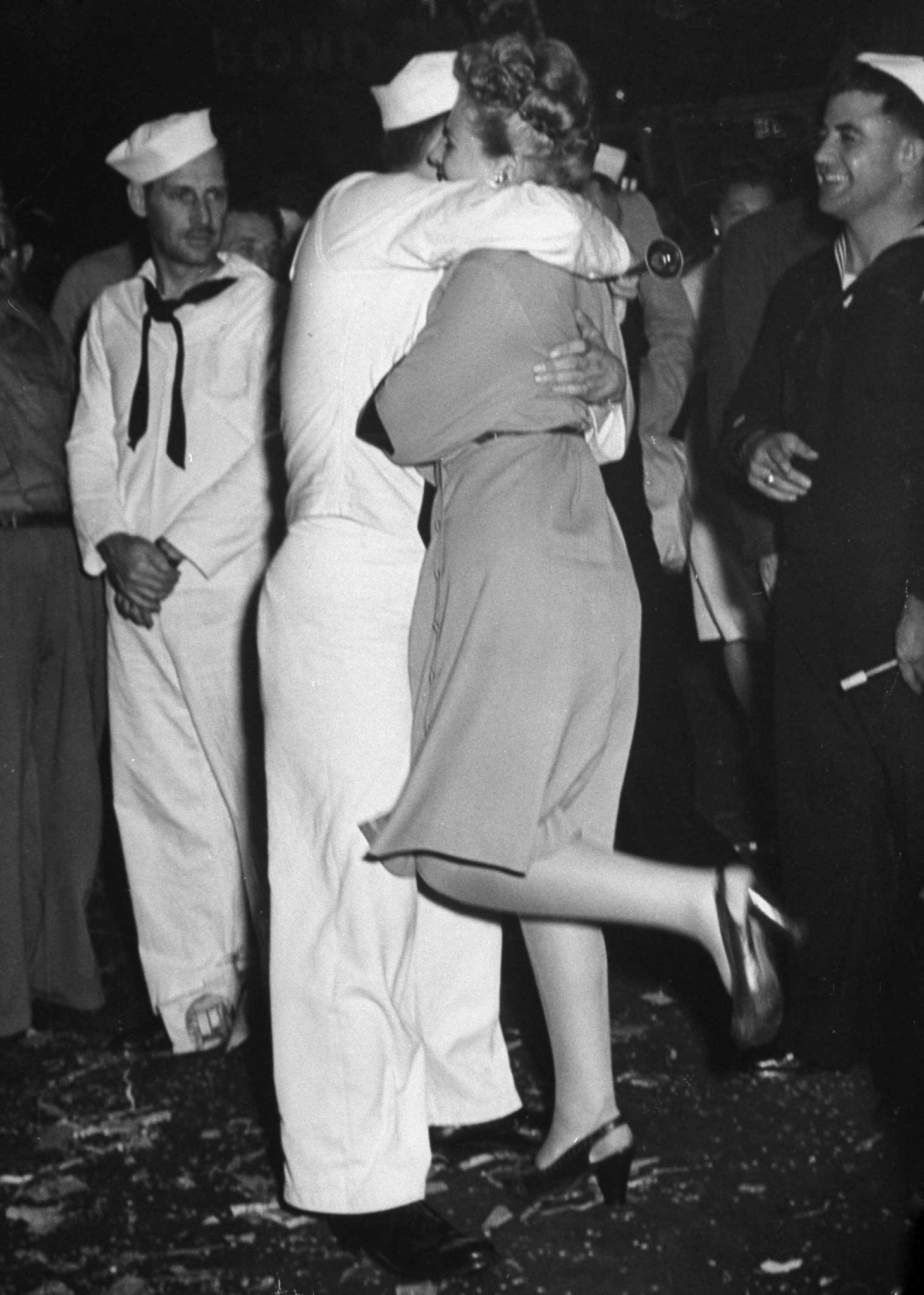

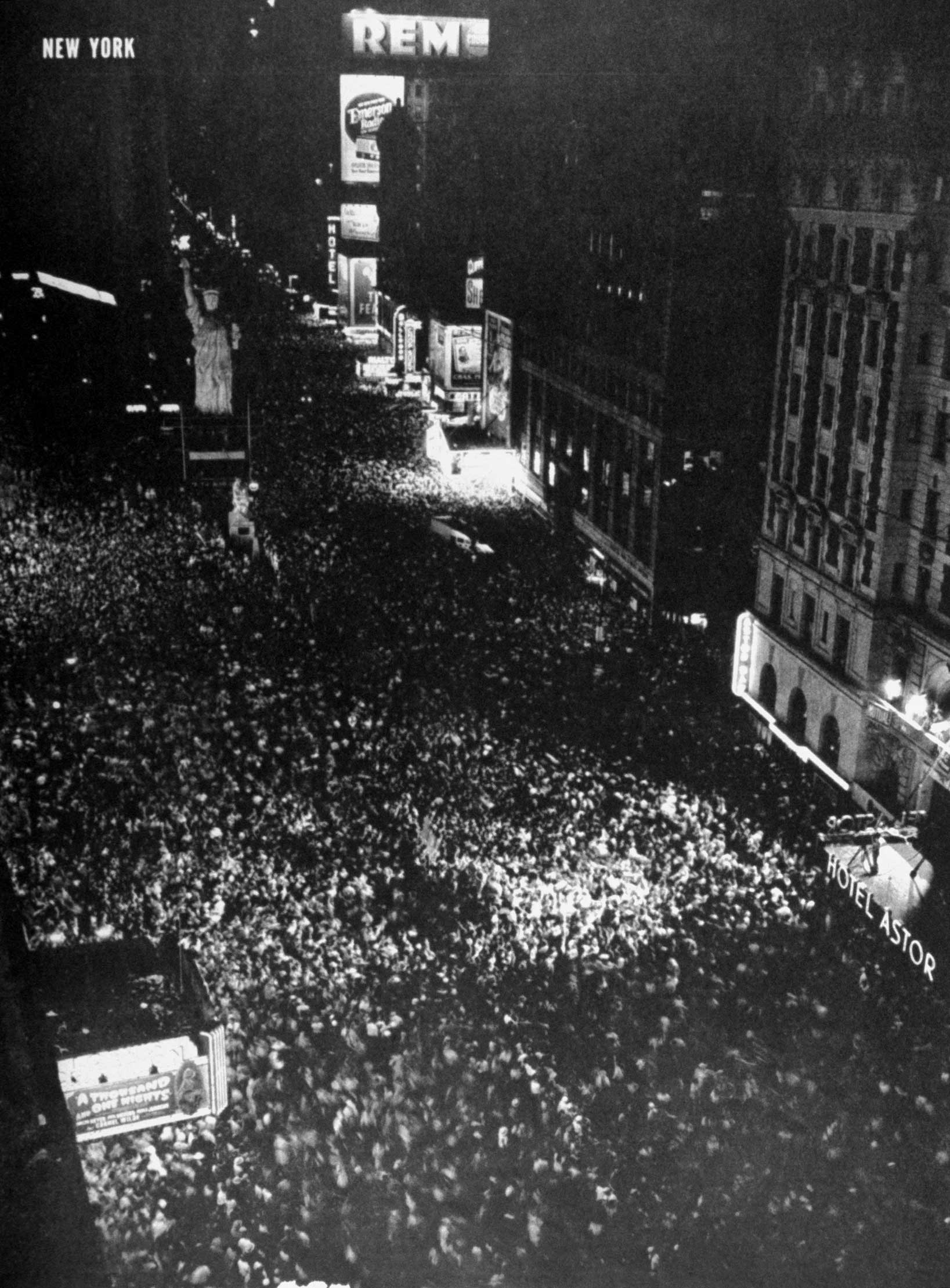

Here, LIFE.com presents not only Eisenstaedt’s storied photograph—and a picture of the man himself, along with a companion, in the midst of the hoopla (at right)—but photos made around the country by other LIFE photographers as word spread that Japan had, indeed, surrendered.

(The ceremony officially ending the war would not take place for another few weeks, when Japanese representatives signed the documents of surrender aboard the USS Missouri battleship in Tokyo Bay on Sept. 2, 1945.)

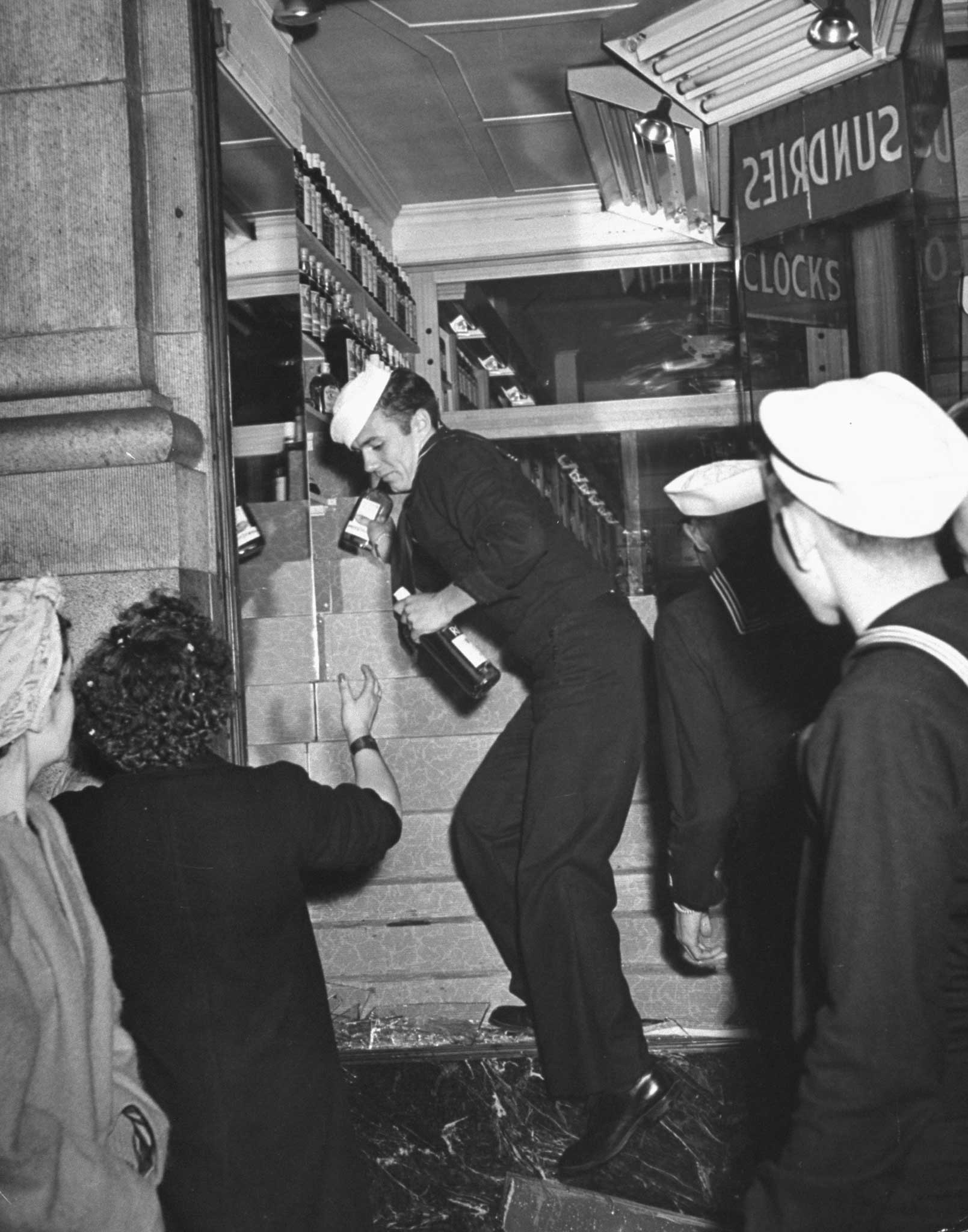

While the joy and relief that surged through the entire country—and across much of the globe, or certainly across those parts of it in which the Allies held sway—was heartfelt, the celebrations in many major cities were hardly all sweetness and light. In fact, as several of the pictures and captions here make clear, some of the tumult unleashed by word of Japan’s surrender quickly devolved into what can only be described as riots.

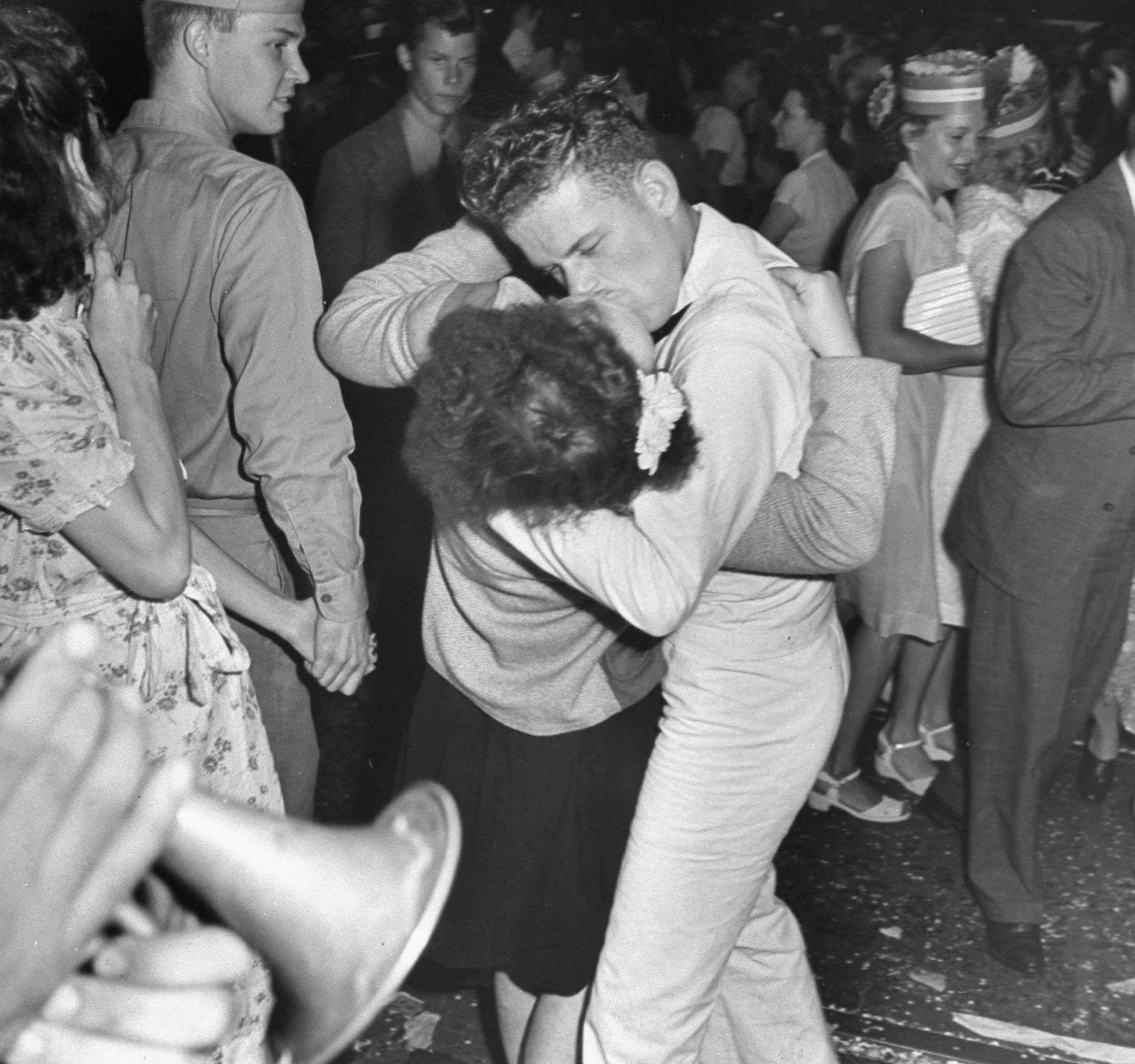

Booze flowed; inhibitions were cast off; there were probably as many fists thrown as kisses planted: in other words, once the inconceivable had actually been confirmed and it was clear that the century’s deadliest, most devastating war was finally over, Americans who for years had become accustomed to almost ceaseless news of death and loss were not quite ready for a somber, restrained reaction to the surrender. That response would come, of course. In time, there would be a more considered, reflective take on the war and on the enemies America had fought so brutally, and at such cost, for so long.

But in the giddy, chaotic first few hours after the announcement, people naturally took to the streets of cities and towns all over the country. And while some of the merriment was no doubt of a quieter, G-rated variety, it’s hardly surprising that countless grown men and women seized the opportunity for cathartic revelry, giving vent to joy and relief as well as to the pent-up anxieties, fears, sorrows and anger of the previous several years.

In other words: the nation let loose.

That sort of revelry is not always pretty. Sometimes it can be downright ugly. But to pretend it doesn’t happen (especially when a record of it exists right before one’s eyes) does a disservice to history; to the memories of the men and the women killed and wounded in the war and of those who lived to mark its long-hoped-for end.

Finally, two small but significant pieces of information related to Eisenstaedt’s rightfully famous “Kiss in Times Square” might come—especially when taken together—as a real surprise to fans of both photography and of LIFE magazine in general.

First, contrary to what countless people have long believed, the photo of the sailor kissing the nurse did not appear on the cover of LIFE. It did warrant a full page of its own inside the magazine (page 27 of the August 27, 1945, issue, to be exact) but was part of a larger, multi-page feature titled, simply, “Victory Celebrations.”

Closely tied to that first point is the fact that, while the conclusion of the Second World War might be something LIFE magazine, of all publications, could be expected to feature on its cover for weeks on end, the magazine’s editors clearly had other ideas. In fact, not only did Eisensteadt’s Times Square photo not make the cover of the August 27th issue; no image related to the war, or the peace, graced the cover. Instead the magazine carried a striking photograph of a ballet dancer. An underwater ballet dancer.

War is over! that cover seems to say. After years of brutal, global slaughter, our lives—-in all their frivolous, mysterious beauty—can finally begin again.

Amen to that.

Credits: Eisenstaedt in Times Square, William C. Shrout—The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images; LIFE cover, Walter Sanders—The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com