The key to containing spread of a virus like Ebola, public health experts tell us, is tracking down every person with whom an infected person had direct contact. Such contact tracing includes people in their family who might have shared hugs or kisses, or health care workers who handled any specimens.

Who is currently being traced in this way? Here’s what we know.

How many people are being monitored?

48 people who had direct contact with Thomas Eric Duncan

For now, officials at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) say that 48 people had direct contact with Thomas Eric Duncan before he was isolated on Sept. 28 and diagnosed on Sept. 30. CDC has not clarified where those people might have had contact with Duncan. Four members of his immediate family who were staying in the same apartment as Duncan since he arrived in the U.S. have been quarantined for 21 days, the incubation period for the Ebola virus. But it’s not clear whether the remaining 44 include public citizens in the same apartment building or whether it also includes others in the community.

76 health care workers who cared for Duncan

Between Sept. 28, when Duncan was put into isolation at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, and Oct. 8, when he died, 76 health care workers participated in his care, performing duties that potentially exposed them to his infectious body fluids. All are being monitored, according to the CDC. At the minimum, that involves having the health care workers take their own temperature twice daily, and report any fever above 100.4F or any other symptoms of Ebola, including nausea, headache, vomiting and diarrhea.

It’s not clear how many, if any, are being actively monitored, which involves public health officials performing the temperature checks twice daily and asking detailed questions about any other possible symptoms.

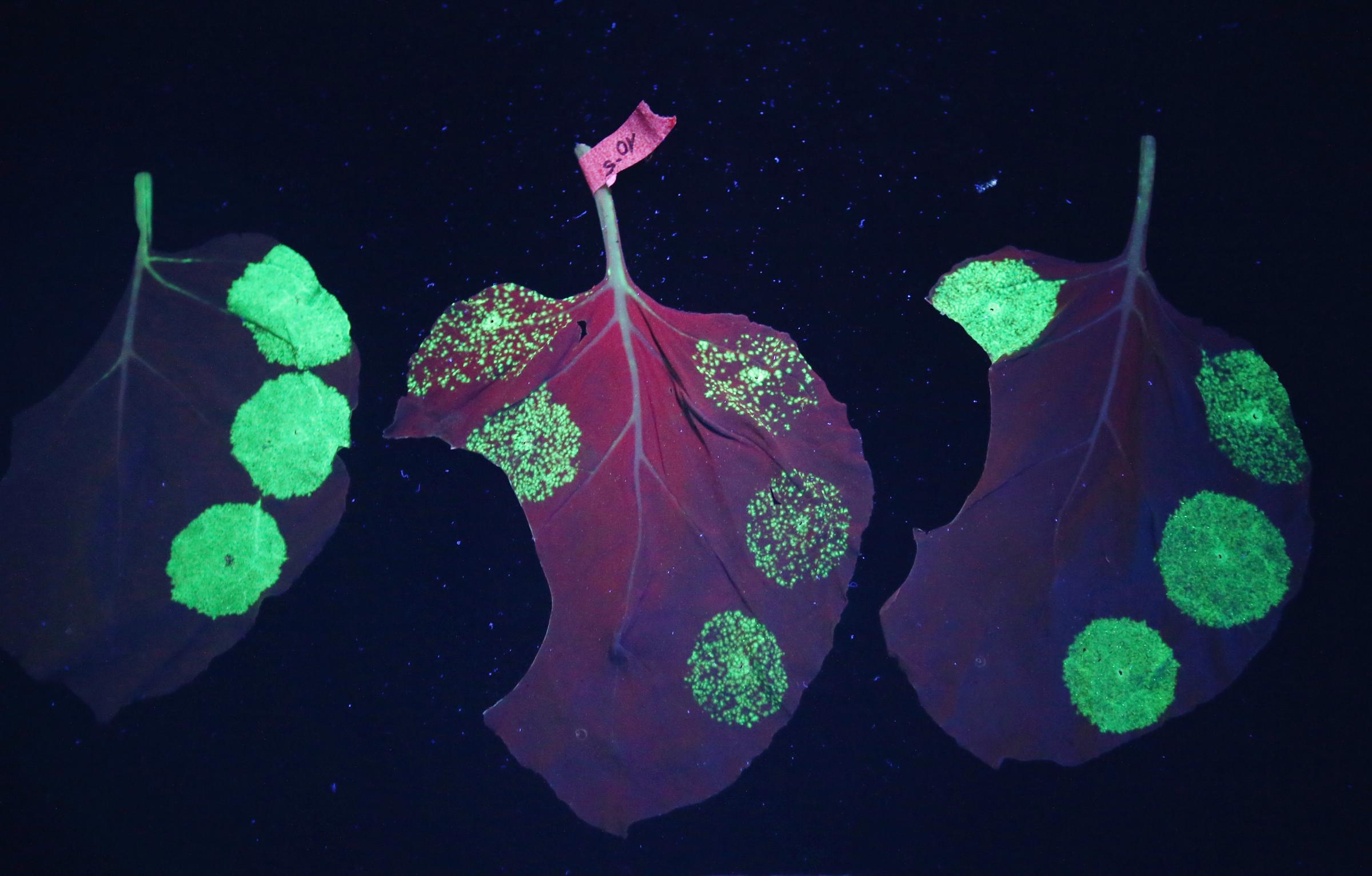

See The Tobacco Leaves That Could Cure Ebola

Can contacts travel?

According to CDC director Tom Frieden, people who are part of contact tracing are advised not to use public transport. They are limited to so-called controlled movement, such as a personal car.

Amber Vinson, the second nurse to test positive, however, traveled by plane from Dallas to Cleveland on Oct. 10, two days after Duncan’s death. Vinson had apparently been intimately involved in Duncan’s care while he was alive, including drawing his blood and inserting catheters. Even if she did not have a fever before she boarded the plane, Frieden said, “because she was in a group of individuals known to have exposure to Ebola, she should not have traveled on a commercial airline.”

While in Cleveland, Vinson reported a temperature of 99.5F. That is below the CDC threshold of 100.4F for Ebola isolation, but because of her direct contact with Duncan’s body fluids, Vinson was told by CDC to return to Dallas, according to a CDC spokesperson. She did, on Oct. 13, on a commercial flight.

Frieden said on Oct. 15 that Vinson reported no symptoms of Ebola; Ebola patients can only spread their disease when they are symptomatic and through direct contact with their body fluids, including vomit, diarrhea or blood.

Why isn’t every contact of Duncan’s under quarantine?

Because Ebola only spreads through contact with body fluids when the patient is symptomatic, the risk of contracting Ebola through casual interactions is very low. Passengers on the plane that brought Duncan into the U.S., for example, are not at risk because he was not symptomatic during this trip.

Passengers on Vinson’s flight from Cleveland to Dallas, however, are being monitored out of an abundance of caution. Because she had a fever, the CDC notified Frontier Airlines, the carrier, that Vinson “may have been symptomatic earlier than initially suspected, including the possibility of possessing symptoms while on board the flight,” according to Reuters. Those passengers are now being monitored for Ebola symptoms.

Duncan’s family members are under quarantine because they were in direct contact with Duncan when he first became ill, and have a high chance of having touched his infectious body fluids.

Health care workers are also at high risk, since they handled Duncan’s body fluids as he became more and more symptomatic in the hospital. They are supposed to be protected from exposure by personal protective equipment, but Frieden acknowledged that the gear used by health workers in the Duncan’s early hospitalization was “variable” and that both Vinson and Nina Pham, the first nurse to test positive for Ebola, might have been infected during this time.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com