In a report published in the journal Lancet, scientists led by Dr. Robert Lanza, chief scientific officer at Advanced Cell Technology, provide the first evidence that stem cells from human embryos can be a safe and effective source of therapies for two types of eye diseases—age-related macular degeneration, the most common cause of vision loss in people over age 60, and Stargardt’s macular dystrophy, a rarer, inherited condition that can leave patients legally blind and only able to sense hand motions.

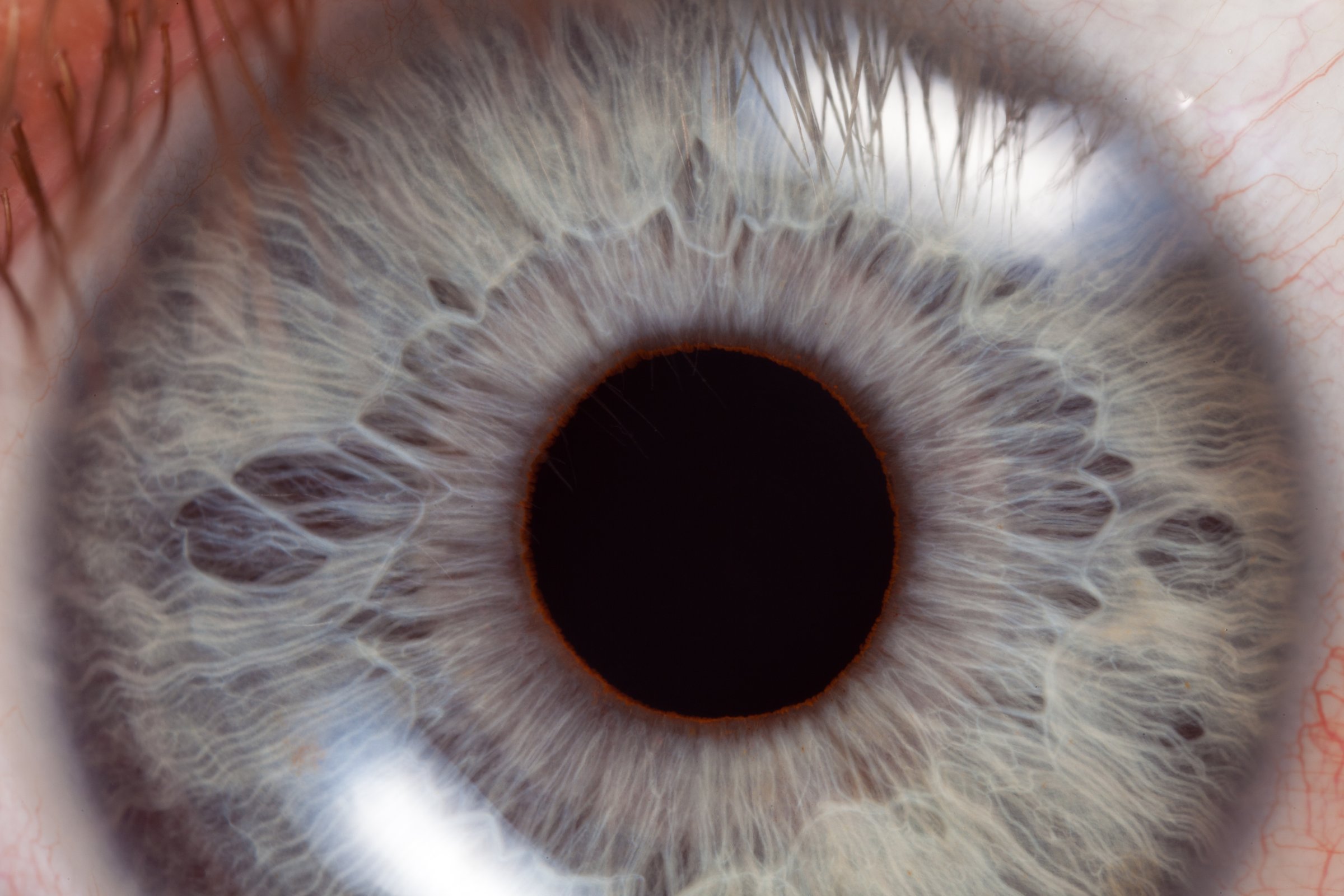

In the study, 18 patients with either disorder received transplants of retinal epithelial cells (RPE) made from stem cells that came from human embryos. The embryos were from IVF procedures and donated for research. Lanza and his team devised a process of treating the stem cells so they could turn into the RPE cells. In patients with macular degeneration, these are the cells responsible for their vision loss; normally they help to keep the nerve cells that sense light in the retina healthy and functioning properly, but in those with macular degeneration or Stargardt’s, they start to deteriorate. Without RPE cells, the nerves then start to die, leading to gradual vision loss.

MORE: Stem Cell Miracle? New Therapies May Cure Chronic Conditions Like Alzheimer’s

The transplants of RPE cells were injected directly into the space in front of the retina of each patient’s most damaged eye. The new RPE cells can’t force the formation of new nerve cells, but they can help the ones that are still there to keep functioning and doing their job to process light and help the patient to see. “Only one RPE can maintain the health of a thousand photoreceptors,” says Lanza.

The trial is the only one approved by the Food and Drug Administration involving human embryonic stem cells as a treatment. (Another, the first to gain the agency’s approval, involved using human embryonic stem cells to treat spinal cord injury, but was stopped by the company.) Because the stem cells come from unrelated donors, and because they can grow into any of the body’s many cells types, experts have been concerned about their risks, including the possibility of tumors and immune rejection.

MORE: Early Success in a Human Embryonic Stem Cell Trial to Treat Blindness

But Lanza says the retinal space in the eye is the ideal place to test such cells, since the body’s immune cells don’t enter this space. Even so, just to be safe, the patients were all given drugs to suppress their immune system for one week before the transplant and for 12 weeks following the surgery.

While the trial was only supposed to evaluate the safety of the therapy, it also provided valuable information about the technology’s potential effectiveness. The patients have been followed for more than three years, and half of the 18 were able to read three more lines on the eye chart. That translated to critical improvements in their daily lives as well—some were able to read their watch and use computers again.

“Our goal was to prevent further progression of the disease, not reverse it and see visual improvement,” says Lanza. “But seeing the improvement in vision was frosting on the cake.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com