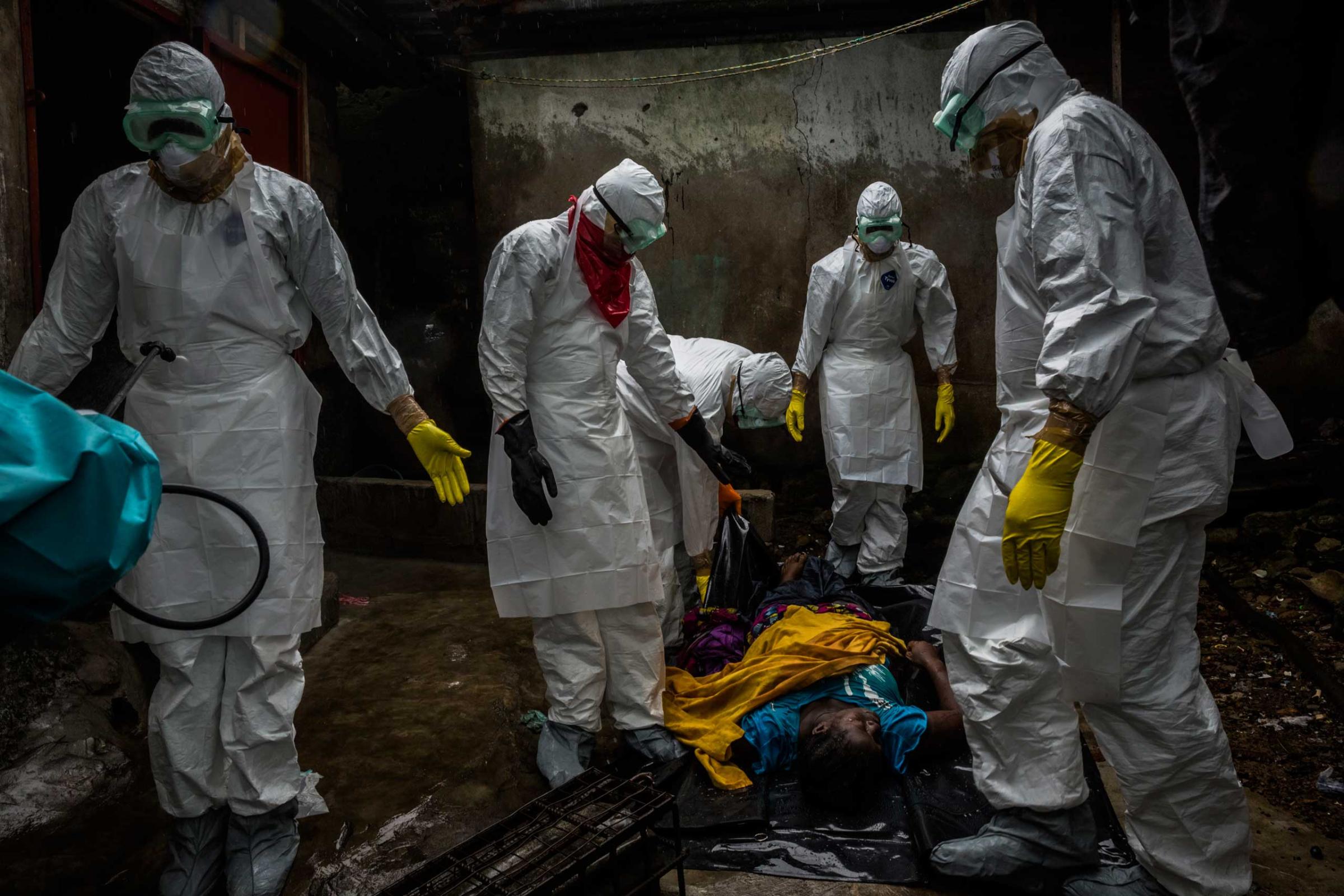

On Sept. 18, photographer Daniel Berehulak and New York Times’ correspondent Norimitsu Onishi were following a body collection and burial team in Monrovia, Liberia, when they visited the home of a woman who had contracted the Ebola virus and died surrounded by her family. “I went inside the house and saw physical proof of Ebola – blood around the victim’s mouth and on the sheets,” Berehulak tells TIME. “Meanwhile, Nori was outside talking to the family and the community. They all claimed Ebola had nothing to do with it.”

On that day, the burial team collected seven bodies and “every single family maintained that it wasn’t Ebola,” says Berehulak. “In some of these places, the burial teams were making their third or fourth visit to the same house.”

For the freelance photographer, the local population’s denial, compounded by a belief that doctors are contributing to the crisis, is further proof that the Ebola epidemic is out of control. Since the start of the outbreak in Dec. 2013, more than 6,500 people have been infected and 3080 have died in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. “In a lot of cases, families take no precautions and the virus is in an environment where it can spread easily,” he says, referring to Monrovia’s dense population and cramped infrastructure.

Berehulak has been on assignment in Liberia for the New York Times for the past five weeks – an unusually long time for such a sensitive and dangerous story [Photographer Samuel Aranda has also been on assignment for the same amount of time for the Times in Sierra Leone]. “Most media outlets have people that stay here for around five to 10 days,” says Berehulak. “Editors are extremely nervous – there’s a lot of pressure and a lot of restrictions.” Yet, covering a story where the “danger is not kinetic,” says Times’ International Picture Editor David Furst, comes with a different set of responsibilities. “This situation, in terms of coordination, is certainly different from what these photographers are used to,” he tells TIME. “I talk to Daniel very frequently about the need to remain vigilant in the procedures and keep safe.”

When Berehulak first arrived in Monrovia on Aug. 22 – armed with 300 pairs of gloves, 35 Personal Protective Equipment suits, goggles, surgical face masks, hand sanitizers and countless rolls of tape – he met with Getty Images photographer John Moore, who had been covering the Ebola crisis for a week. “I spent time finding out how he was working in the field, and I visited one of the Doctors Without Borders treatment centers, which was conducting training for their local staff.”

For several hours, Berehulak watched how the NGO’s staff members were preparing for high-risk areas – “sealing off every single part of the body so that nothing is exposed,” he explains, “taping off the edges of the PPE suits to the facemasks, ensuring that only the eyes are visible before putting on goggles.” He also studied the lengthy process involved with dressing down once out of infected areas – how to take off your gloves, how to use chlorine and how to dispose of your PPE.

That process is essential, says Furst. “It’s the only way you can mitigate the risks, and even though, after covering this heartbreaking situation day-in and day-out, you’re tired, you still need to make sure that you’re following the process of dunking your equipment into chlorine, using the appropriate gloves and wearing your PPE, despite whatever exhaustion you may be feeling.”

Fatigue, in fact, also has to be managed, especially considering the extended period of time Berehulak has spent on the field. “Daniel and I talk a lot about that,” says Furst. “We make sure that he takes days off to relax, to rest and to gather his strengths. We also talk frequently on whether he has the strength and is able to remain focused mentally on what is clearly a difficult story to cover.” Yet, there are also advantages to long-term assignments. “Daniel now has a lot contacts in Monrovia and he has a very good understanding of how to work in that environment. Plus, he very much wants to be there and presses me to stay.” Especially, Berehulak adds, since the situation is far from being over. “This is pretty dire. There are people dying in front of treatment centers because they are full. It seems to be getting worse and the biggest problem is this denial within local communities that Ebola is real.”

Earlier this month, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that, in its worst-case scenario, the number of Ebola cases could reach 1.4 million by January.

Berehulak sees signs of hope, but they are fleeting. “I’d like to think that the outreach is working thanks to the Ebola Response Teams and the Contact Tracking Teams, which are going out to find the source of all infections. But I think it’s going to take time before we see any visible changes, especially in such an urban environment as Monrovia with small alleyways and a dense population.”

Until then, there’s little doubt that more people will die, and Berehulak feels he has a responsibility to help raise awareness of how dire the situation is. “There’s been talk of whole villages where the entire adult population has been decimated,” he says. “So I’m planning to stay for another five to six weeks, but, of course, it’s up to David. He makes the call.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com