Coming at a time of year distinguished by tasteful biopics and elegant prestige dramas, Birdman (opening in limited release on Friday) makes its impact felt by doing something entirely different. The new film by director Alejandro González Iñárritu tells the story of Riggan Thomson (played by real-life Batman star Michael Keaton), an actor best-known for a long-concluded superhero franchise, in his attempts to mount a Broadway adaptation of the work of Raymond Carver. Impressively, it does so in what appears to be a single take.

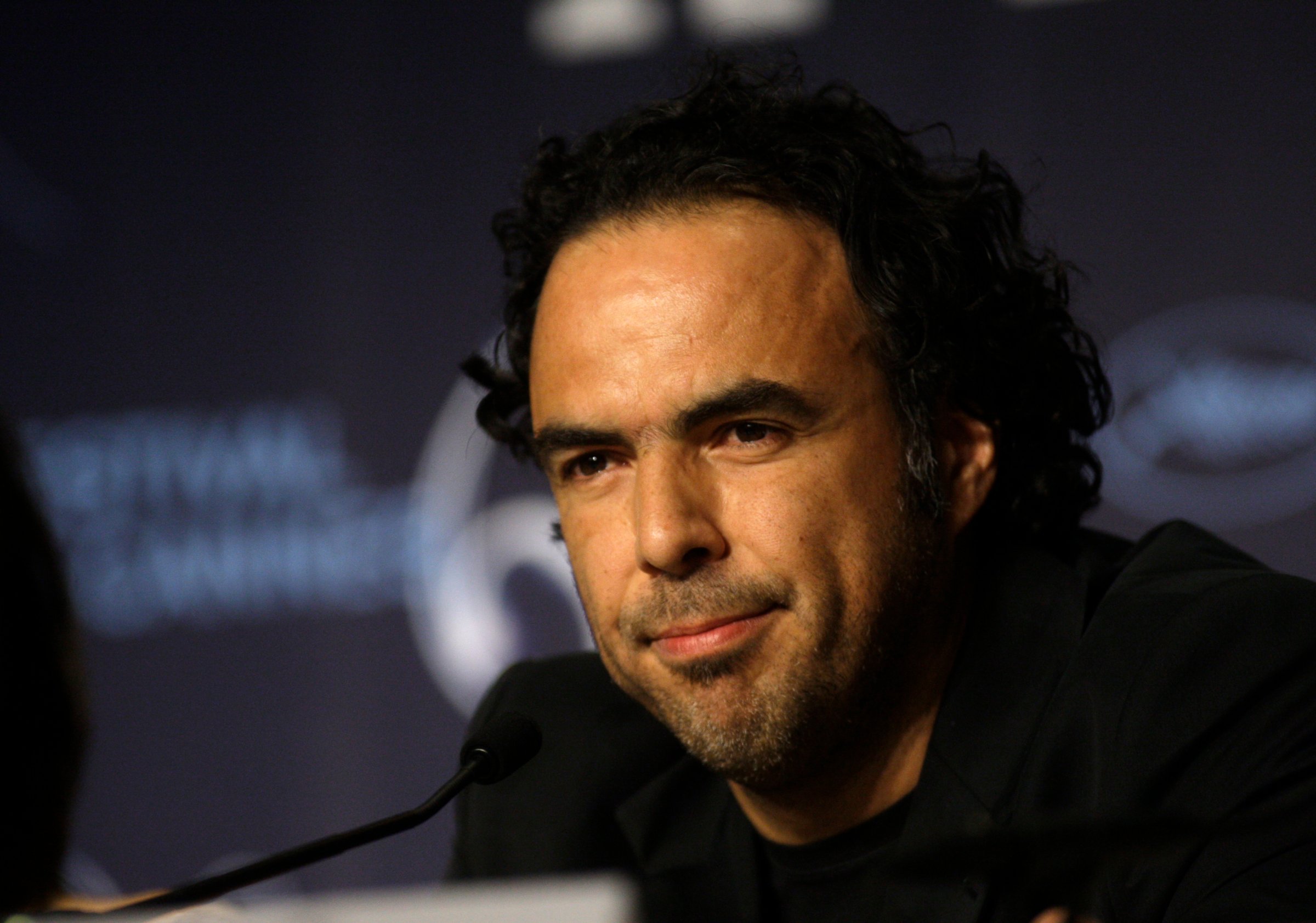

The camera moves seamlessly through a real Broadway theater and the surrounding street as days pass, opening night approaches, and Thomson’s mental state deteriorates. In contrast to his protagonist, who struggles with substances, difficult costars, and an archnemesis from the New York Times, González Iñárritu seemed confident and calm. (It may help that he’s been through it all before: Though Birdman represents a technical step forward, the director of Babel and Biutiful has been the subject of complicated, much-heralded productions before.) Speaking to TIME just after his film’s debut at the New York Film Festival, González Iñárritu described the perfectionist voice inside of him, why he doesn’t care about superhero movies, and why Alfred Hitchcock’s similarly single-shot film Rope is “mediocre.”

TIME: How are you?

Alejandro González Iñárritu: Tired and hungover.

Were you nervous that the apparent single take would overshadow the thematic content of your movie — that it’d be seen as a stunt?

I was very aware of that, and I didn’t want it to take over the film and become a distraction. That’s why I tried to submit that approach in a very humble way, in a way that wouldn’t be showy. All the choices we made were serving the purpose and dramatic tension of the characters, not about “Look how impressive we can be.” All the shots were meant to serve the narrative of the film, not to be showy; there’s no one shot that doesn’t propel the purpose of the whole thing.

I hope that it succeeds, but it’s impossible not to notice. The first time people saw it, they noticed something was weird around twenty or twenty-five minutes in. And I was very happy about that — that people, when they saw it the first time, first noticed something weird twenty or twenty-five minutes in. That’s good! That means it is not distracting. You feel it but don’t see it.

What do you think of big-budget action movies like the movie franchise within Birdman? Did they inform your work?

I’ve seen a few of them, because I have a 17-year-old boy, so I go with him. I think now he’s a little bit out of that, thank God. But I would go with him sometimes. What’s fascinating is that he’ll come home and I’ll ask how the movie was. “Great, fantastic!” I’ll ask what it was about. “I don’t know, but it was great!” Either it was about nothing or he doesn’t care. It’s just about popcorn or candy, the visual s— and not what’s related to the story. It’s the same story told hundreds of times, each time with more explosions, loudness, and absurdity. I was conscious of that nonsense. That’s why I put that bird in there. Who the f— is that? Well, who cares! It looks cool. Exactly! It’s cool for two minutes, but one and a half hours of coolness is too much for my personal taste.

Your movie comes down hard on the character of the theater critic (played by Lindsay Duncan); she’s portrayed as venomous and biased. What were you drawing on here? Critics seem to love your movies!

First of all, remember that everything is basically in the fearful and uncertain mind of Riggan Thomson. In the beginning, he’s floating in his underwear. Everything comes from that point of view; everything’s happening in his fearful mind. And the critic represents what he has been fearing all this time, which is to be judged. And I think that in the theater scene, it’s not a secret that a few people have the power to finish a production. It’s a reality and everyone knows it. It’s almost like a dictatorship, represented by Lindsay Duncan playing a critic who has enormous power and incredible disrespect for what Riggan Thomson represents. She tells him she hates him and what he represents — they are polar opposites. What she says to him is right, and it’s powerful. Is it based on something personal? No! It’s truthful to the universe of the film. As the camera, I try to subordinate every word to be truthful and honest to each character’s context. Is it personal commentary? No, it just makes sense there. And believe me, I have many critics who say, “I know somebody like that exactly.” And that’s funny. People like that exist.

Do you have any Riggan-style anxiety over how critics or the public are going to react to this movie come opening night?

Anyone who says they don’t care is lying. Obviously, you want to be accepted and liked. But at the same time, there’s nothing I can do anymore. What’s done is done. I’m proud and happy of the film. It was a beautiful and fun experience to be allowed to be that irresponsible. To make a film with one shot, with comedy and drama, all of that craziness — God bless the people who gave money — all of that craziness, to be able to do that was an incredible right for me as an artist. If the box office is great, fantastic. If not, I will be as proud.

This is your first movie that doesn’t use the Spanish language or Latino actors at all. Did you feel less at home?

No, I never thought about that. It was a film born to be played here and shot in New York. I never thought about it.

In Birdman, Michael Keaton’s character wants so badly to be more than how he’s been pigeonholed, but that’s also really destructive. Do you ever feel, as a creative person, as though compromise might be easier?

On the contrary! I think my creative process, personally, is full of that kind of voice, of Birdman. I have my own Birdman, who’s a motherf—er, dictator, tyrannical figure who misleads you. It’s cruel. And he’s always unsatisfied — good or bad, it’s going to be the same, always questioning, saying “It could have been better. You are this, you are that.” Once I realized that through meditating for more than five years, I can see clearly that there’s a mechanism of that voice that we all have who can really tell you how great you are and 20 minutes later he’s just tearing you to pieces. If you don’t realize it, it’s dangerous — most dictators and superego guys are really dangerous because they’re attached completely to that voice without realizing that it’s them! They’re delusional about it. And that’s what Riggan Thomson is dealing with; it was an exploration of how the creative process can drive you crazy. There were moments in the film I was feeling like Riggan Thomson, it was very difficult to get that one-take thing. It was extraordinarily new for me and we had to discover a way to do it.

Did you ever wish you’d planned to shoot the film conventionally, given how much of an undertaking it was?

No. I would have never done the film like that. The idea and the form were born together. It was a monolithic piece that couldn’t be shot conventionally. The experience of the film is completely different, and that part was exhilarating for me. It was risky! Every scene — good or bad — I had to leave in. It was an endless strand of spaghetti that could choke me! Every note had to be perfect.

But Birdman isn’t the only movie in history to have been made to look like a single take. Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope is the famous example, and there’s also the 2002 film Russian Ark.

There’s always this comparison with Rope, which I think is a terrible film. I don’t like it. I think it’s a very bad film of Hitchcock’s. It’s a very mediocre film. Obviously, he shot with that intention and it didn’t work — because of the film itself! It has nothing to do with the technique, it’s just a mediocre film. Russian Ark, I adore — I almost cried at the end of that film, it’s so beautiful. But more than anything, if there’s an influence here, it would be [Lola Montes and La Ronde director] Max Ophuls. Every film of Max Ophuls contains a sequence that’s long and beautifully choreographed, always serving the magic and purpose of the character, and the context. If there’s someone that needs to be watched in that sense, it’s Max Ophuls — or Robert Altman or Sidney Lumet.

I didn’t know how to do it, but I tried and I really had fun doing it. For me, personally, I reflect now on how much I have over-abused editing. We over-cover [shooting scenes from various angles to ensure there will be a polished final cut]. There’s no need for so much cover. It’s better when you’re clear and engaged because it’s more powerful on every level. The way films establish the order of scenes is very artificial. And now when I think of my old films, I think, “Why did you shoot like that?” It looks very artificial! It’s fragmented. Now, I don’t see cinema the same way as I did before Birdman. It was an experiment that affected my whole approach to fiction.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com