“Happy families are all alike,” Tolstoy famously observed, “but every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” But the opposite might well be said of those most volatile of family members: teenagers. Every happy teen, after all, is happy in his or her own way; but unhappy teens are all alike.

This hardly diminishes, of course, the issues forever bedeviling teenagers: navigating a maelstrom of unleashed hormones; confronting the riddle of how (or whether) to try to fit in with one’s peers; exploring the limits of rebellion against . . . everything. Even one of the saving graces of teen misery — namely, the eventual realization that everyone, to some degree, suffers the same cruelties during those confounding years — is merely acknowledgement that adolescence can be a waking nightmare.

That said, in very few societies is the idea of youth as fraught as it is in Japan. The nation’s culture of conformity — so often remarked on by outsiders, sometime to the exclusion of other aspects of the country — is an elemental reality of Japanese life. And with that culture of conformity comes a drive to rebellion that can, and has, at times resembled a quest for self-negation.

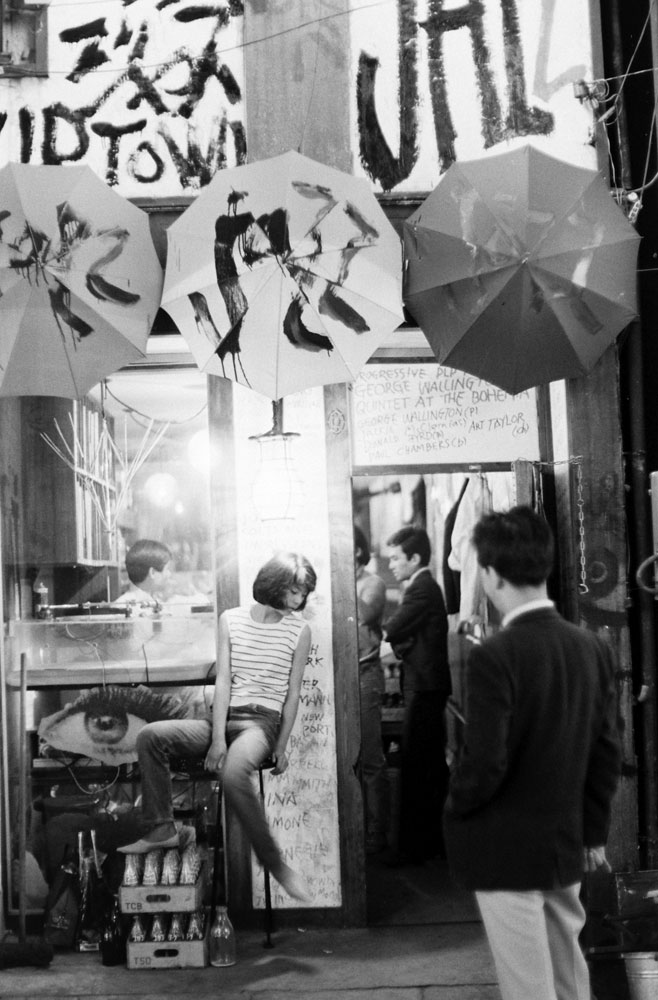

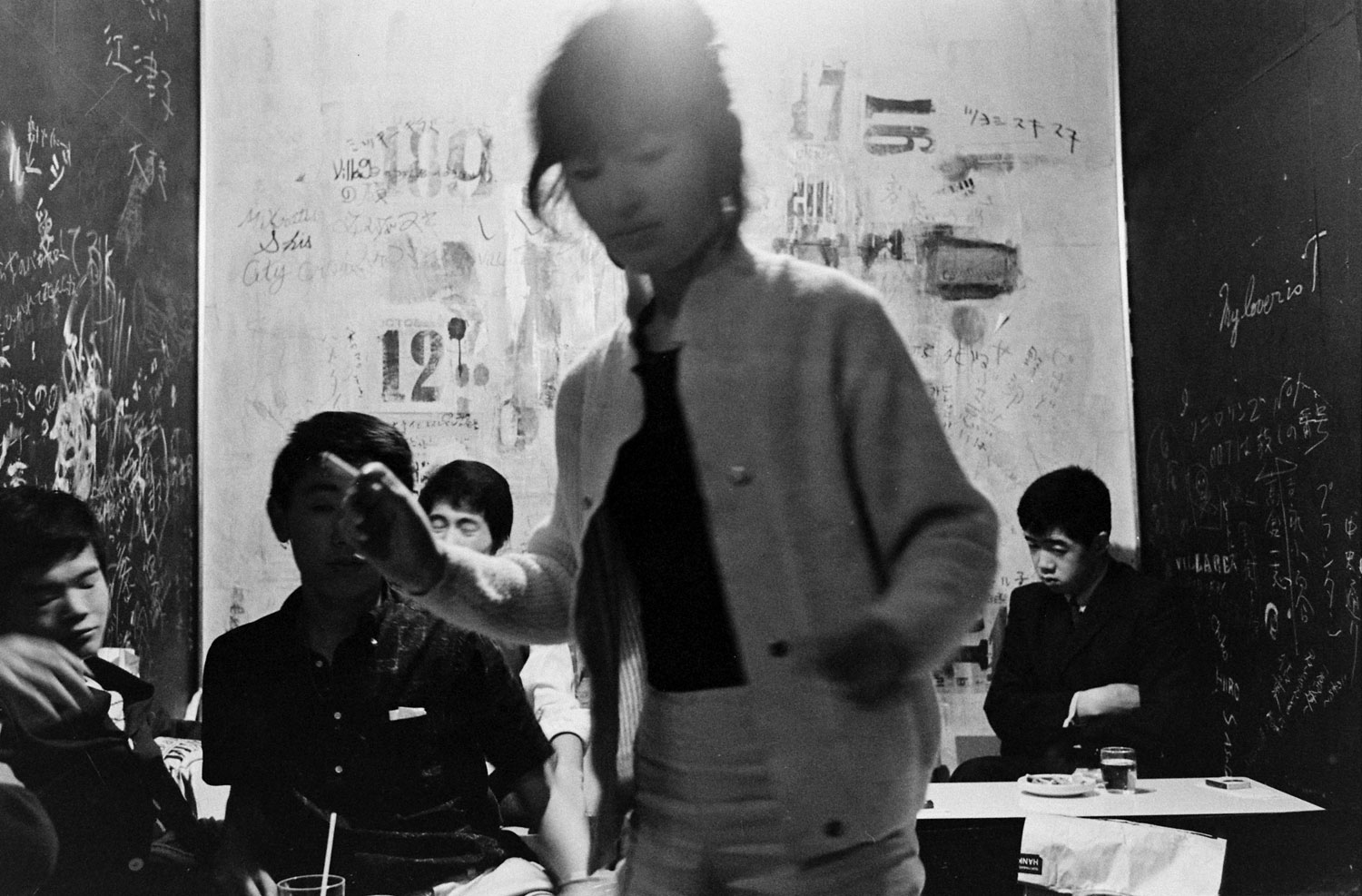

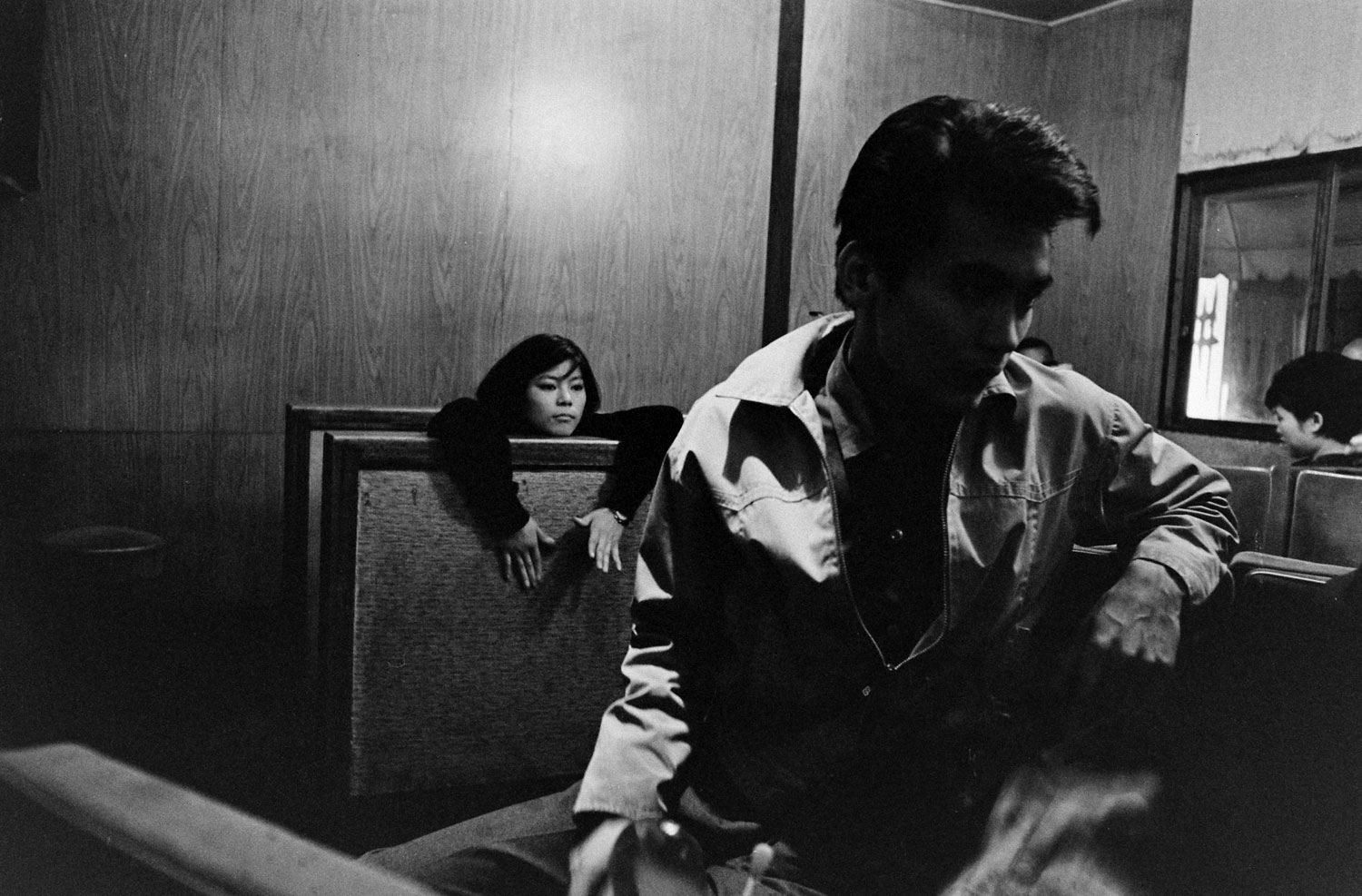

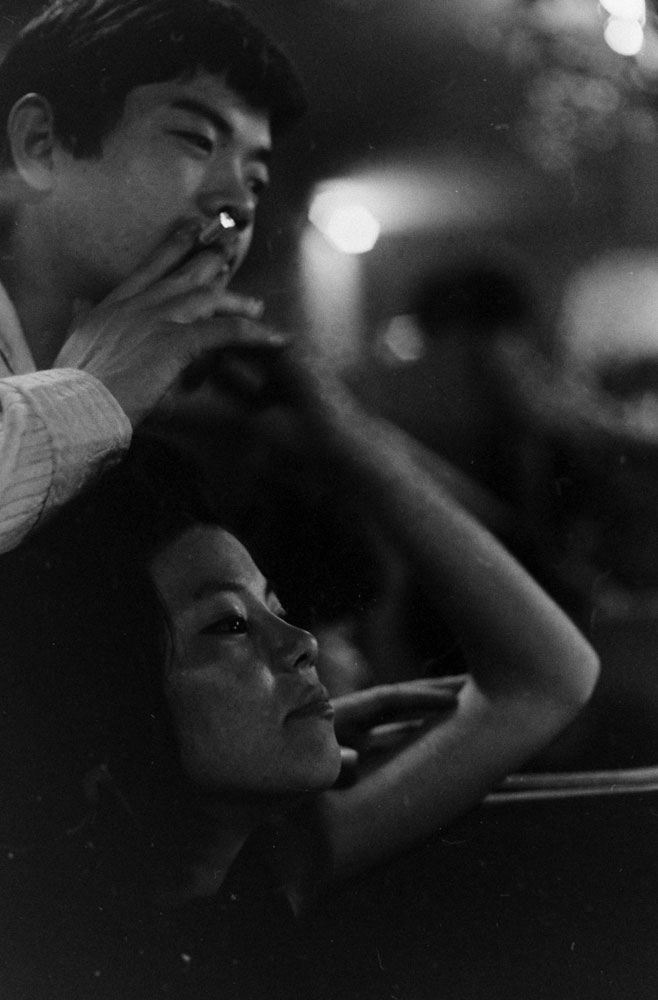

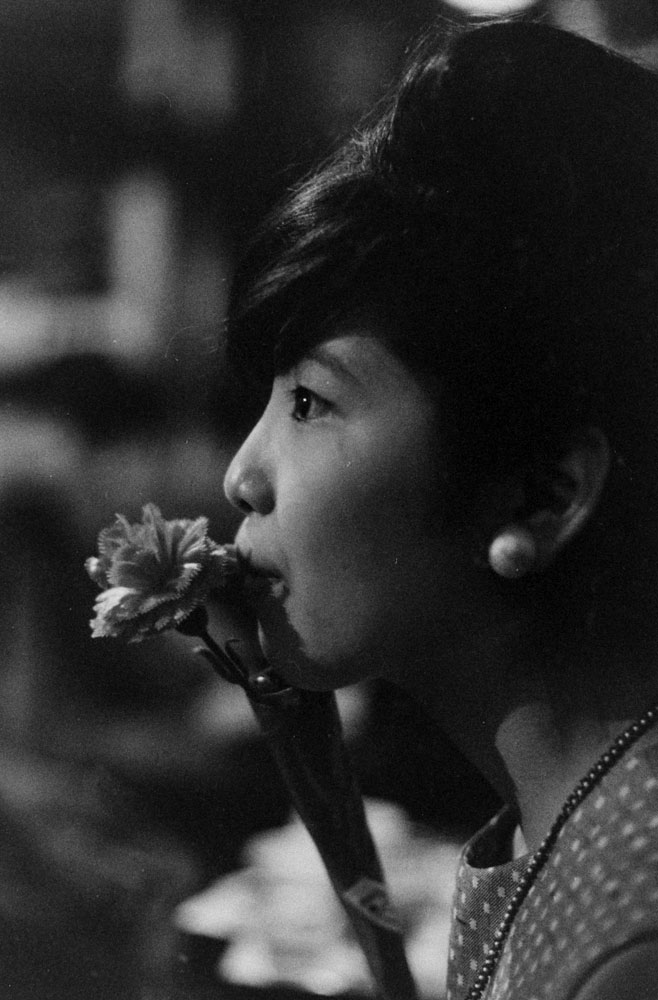

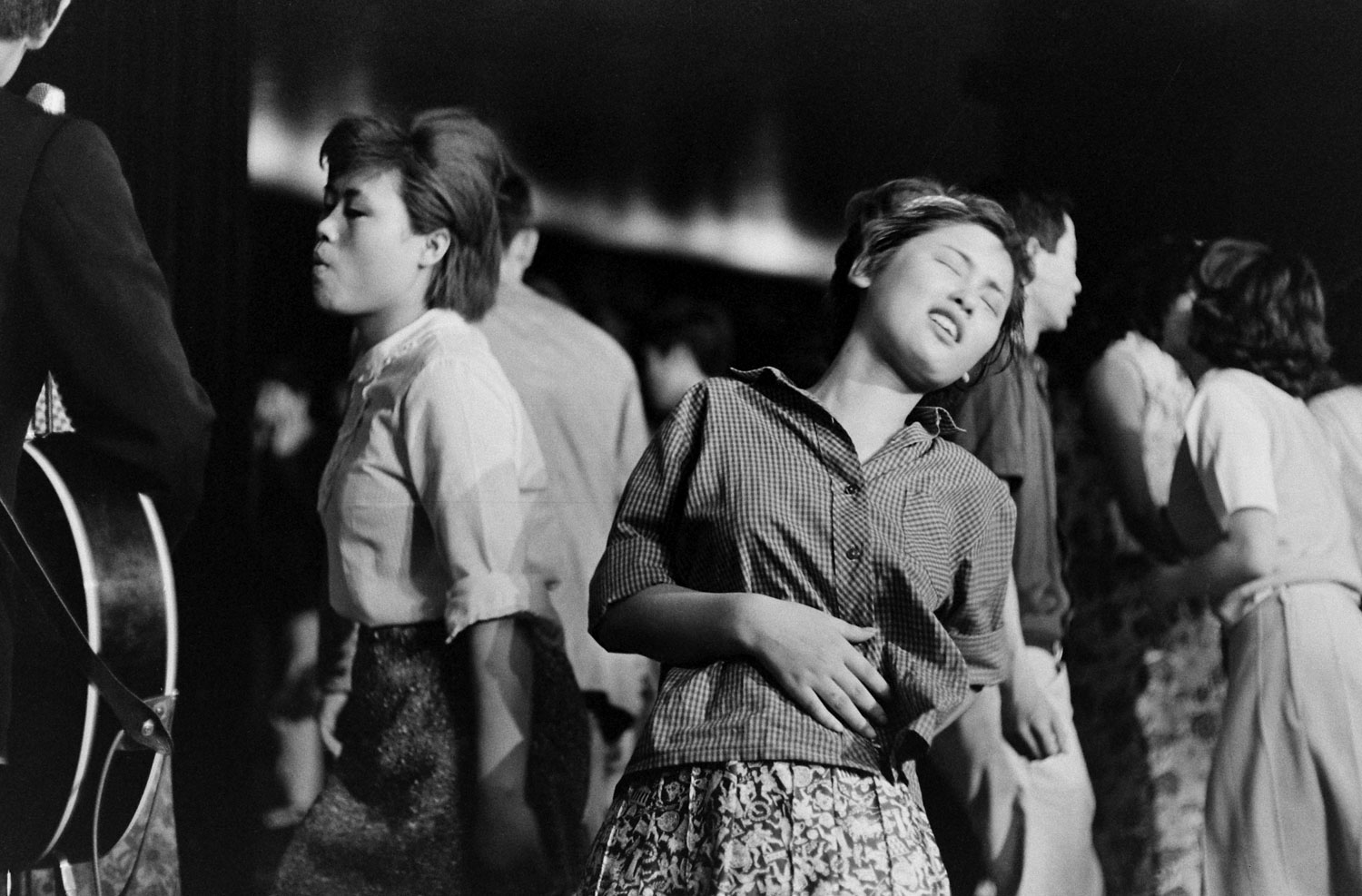

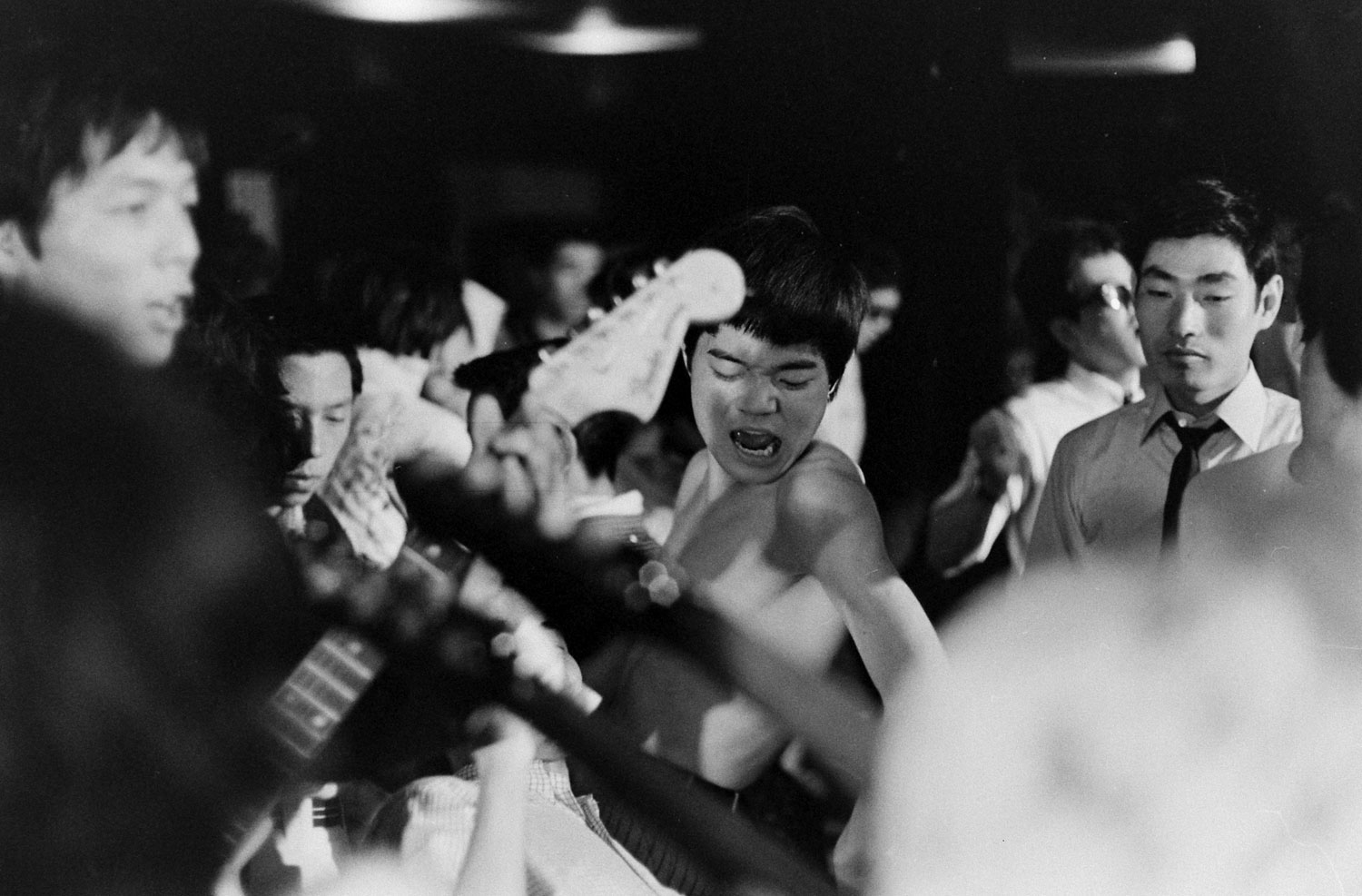

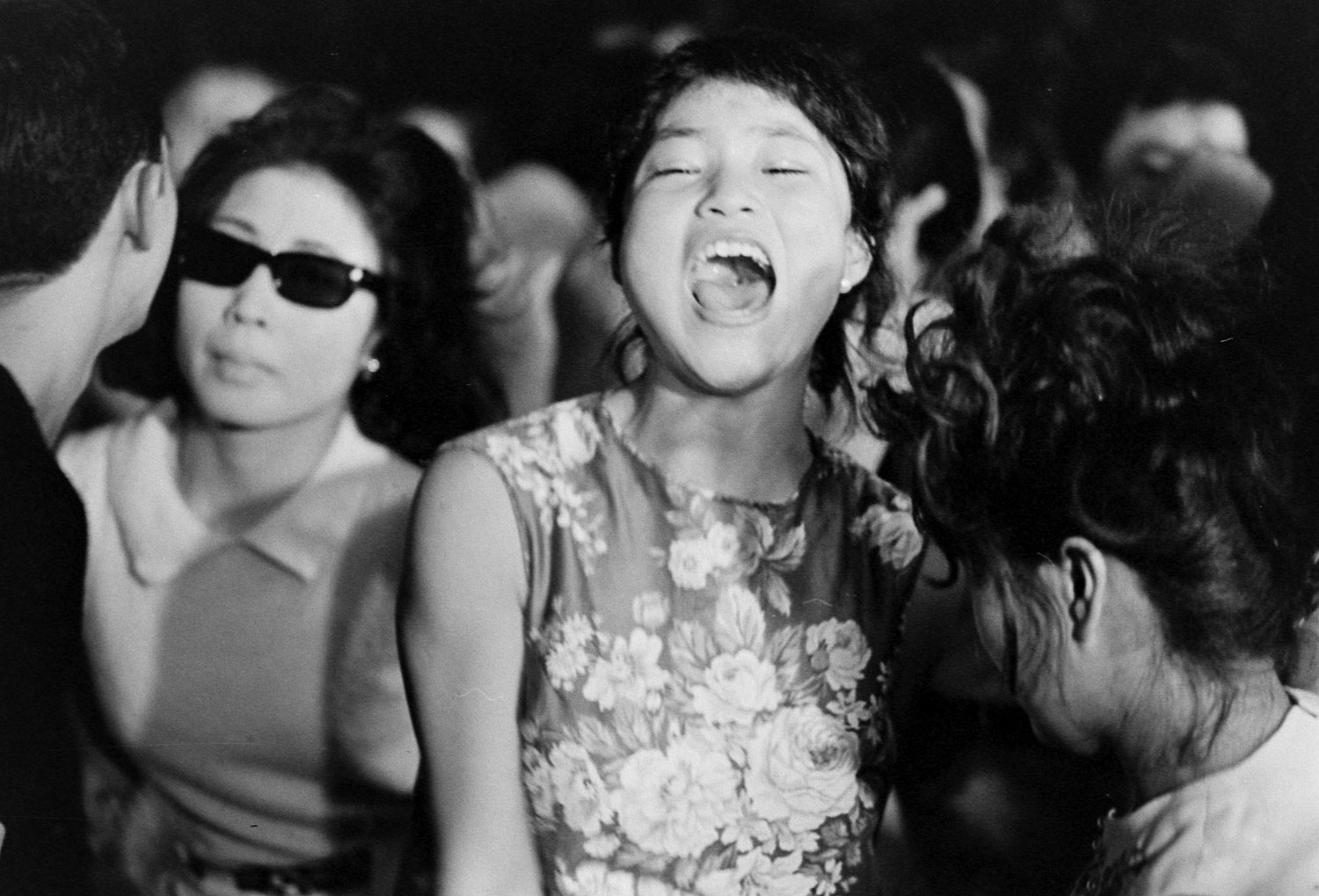

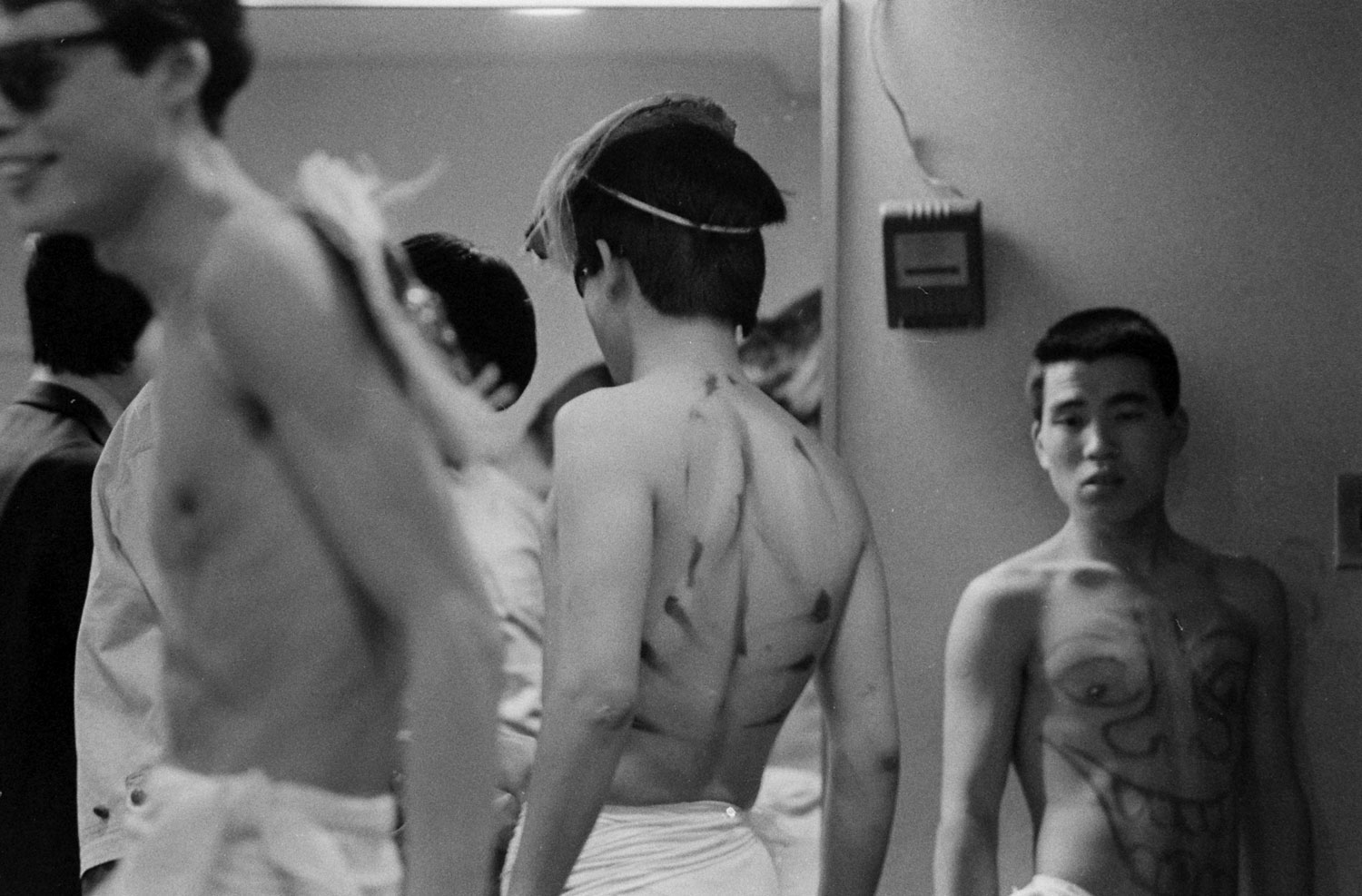

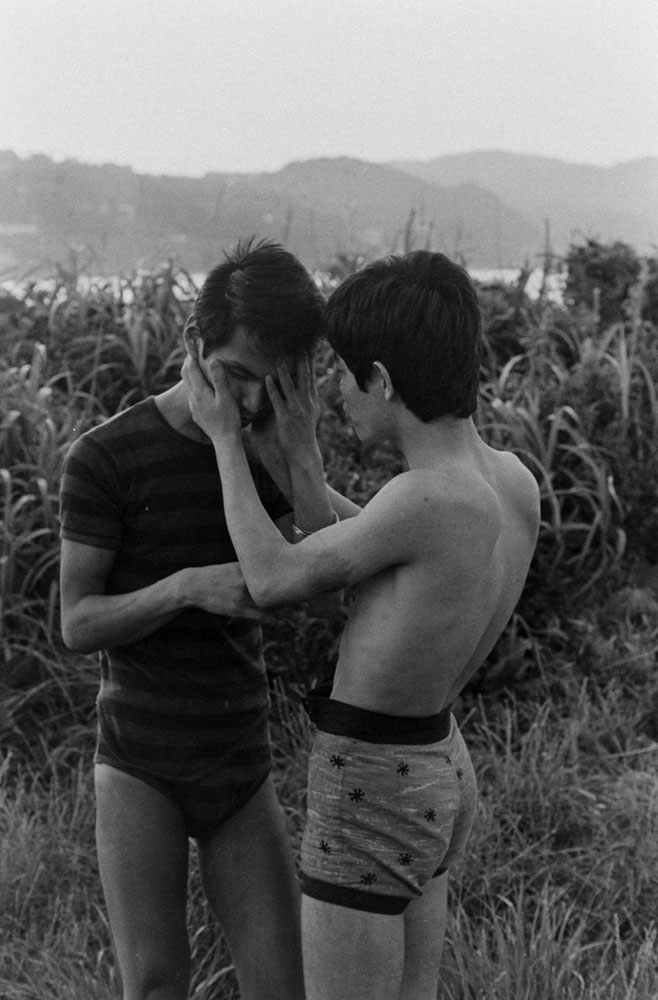

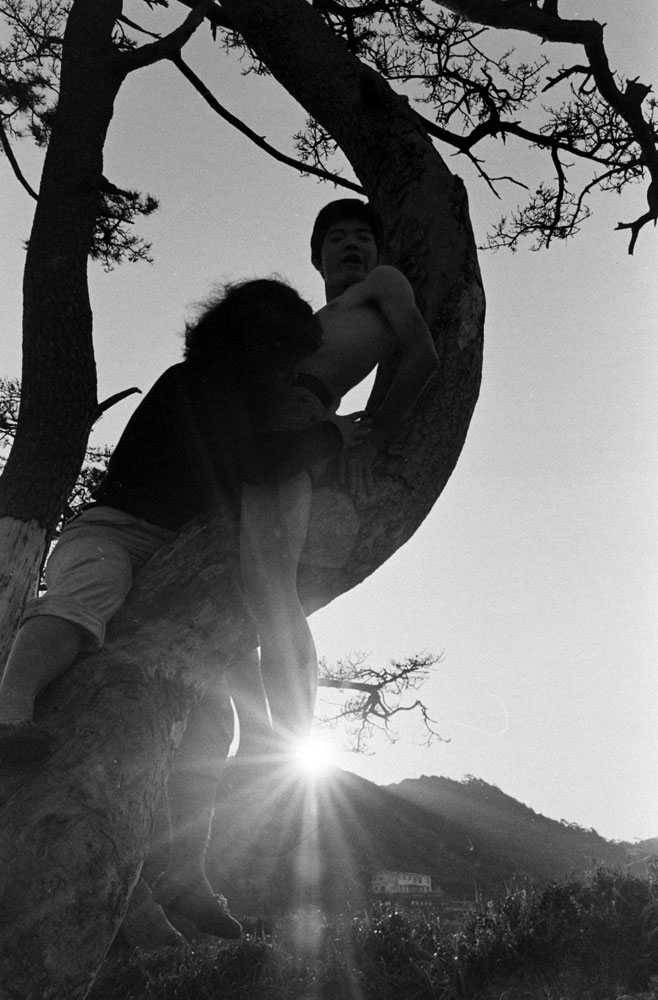

In 1964, LIFE photographer Michael Rougier (at right, on assignment in Tokyo) and correspondent Robert Morse spent time documenting one Japanese generation’s age of revolt, and came away with an astonishingly intimate, frequently unsettling portrait of teenagers hurtling willfully toward oblivion.

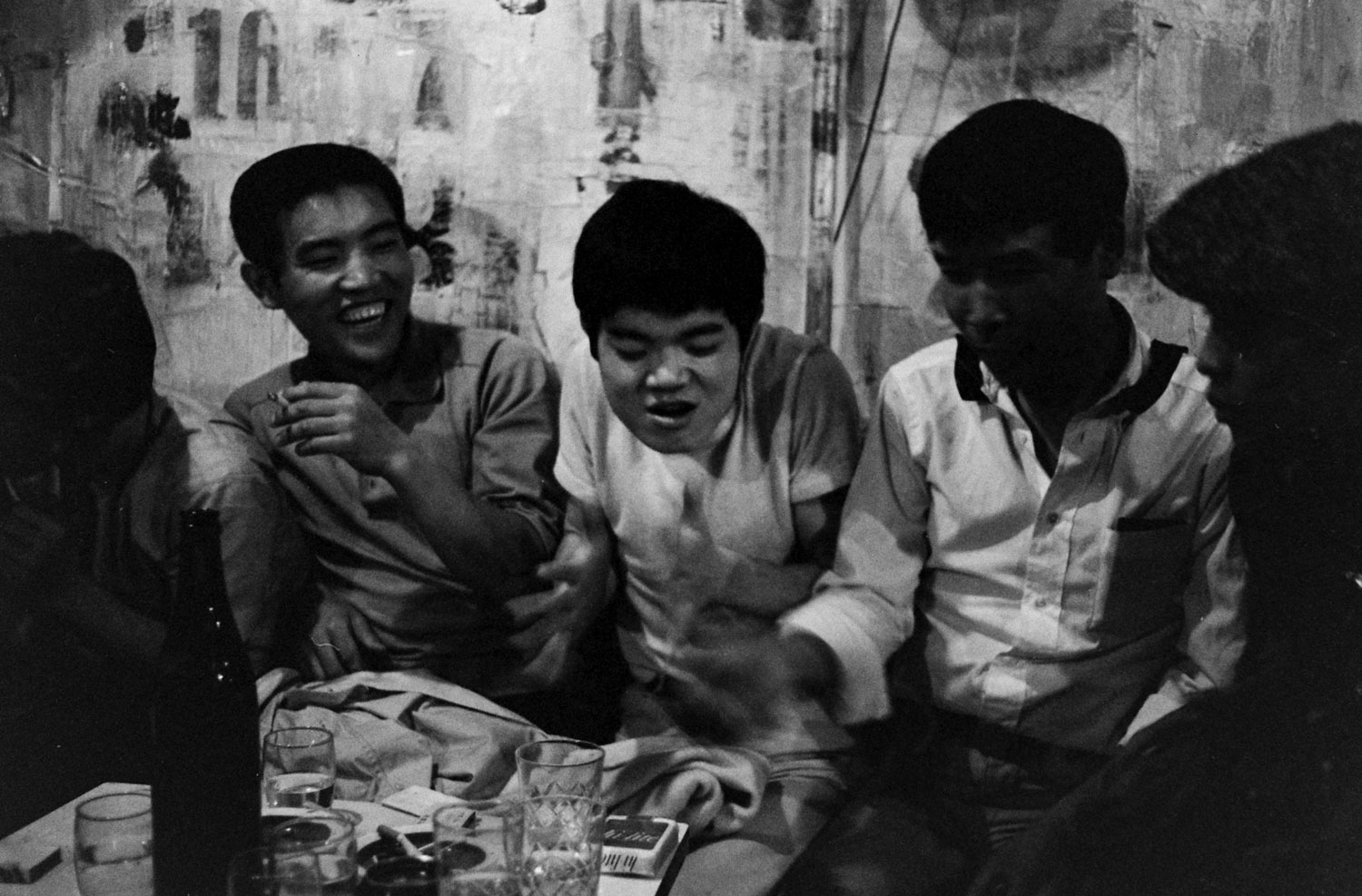

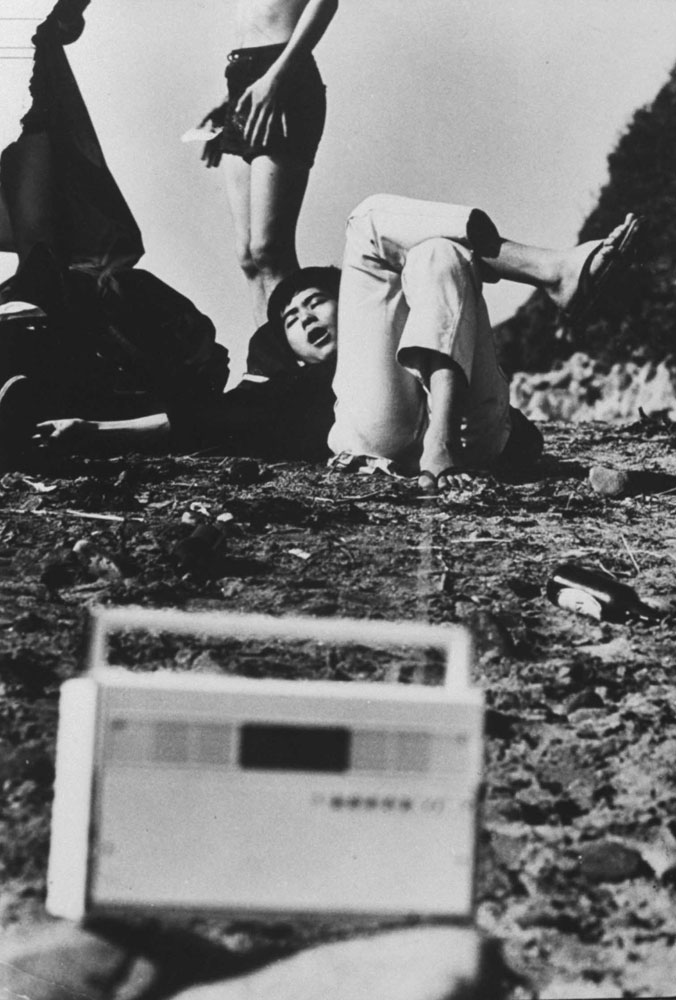

In Rougier’s photos — pictures that seem to breathe both reckless energy and acute despair — we don’t merely glimpse kids pushing the boundaries of rebellion. Instead, we’re offered the rare and disquieting gift of complicity: this generation of lost boys and girls, Rougier’s pictures suggest, is trying to tell us something — something reproachful and perplexing — about the world we’ve made.

Or rather, the world we’ve broken.

The teens and other young adults portrayed in Rougier’s pictures, Morse noted in a 1964 LIFE special issue on Japan (where some of these images first appeared), are “part of a phenomenon long familiar in countries of the Western world: a rebellious younger generation, a bitter and poignant minority breaking from [its] country’s past.”

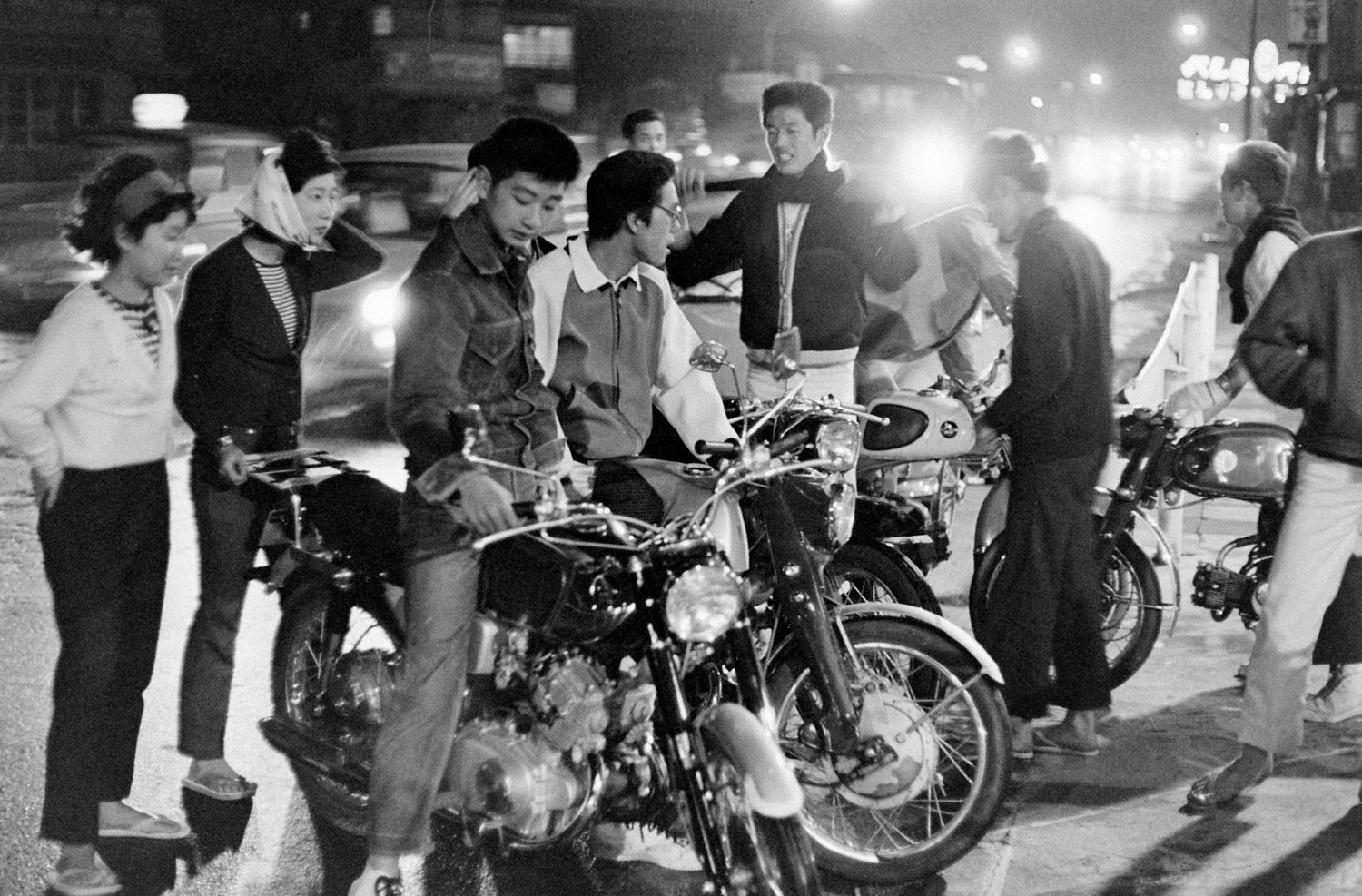

All through that past, a sense of connection with the old traditions and authority has kept Japanese children obedient and very close to the family. This sense still controls most of Japan’s youth who besiege offices and factories for jobs and the universities for education and gives the whole country an electric vitality and urgency. But as its members run away from the family and authority, this generation in rebellion grows.

In notes that accompanied Rougier’s film when it was sent to LIFE’s, Morse delved even deeper into the lives, as he perceived them, of runaways, “pill-takers” and other profoundly disengaged Tokyo teens:

Nowhere in the world does youth seem to dominate a nation as they do in Japan. They are overwhelming and everywhere, surging, searching, experimenting, ambitious at some times, helpless and without hope at others. Isolated on a tight little island, they have not, except on the surface, become international like their counterparts in freewheeling Europe.

Seeing the well-scrubbed faces of the black uniformed male students and middy-bloused girls swarming through Tokyo, physical-fitness minded young men galloping through the Ginza, and the bright young things clamoring after a teen-age idol, it would seem to the casual observer that here is a country with a youth as wholesome and happy as a hot fudge sundae.

This is not true at all.

A large segment of Japanese young people are, deep down, desperately unhappy and lost. And they talk freely about their frustrations. Many have lost respect for their elders, always a keystone of Japanese life, and in some cases denounce the older people for “for having gotten us into a senseless war.”

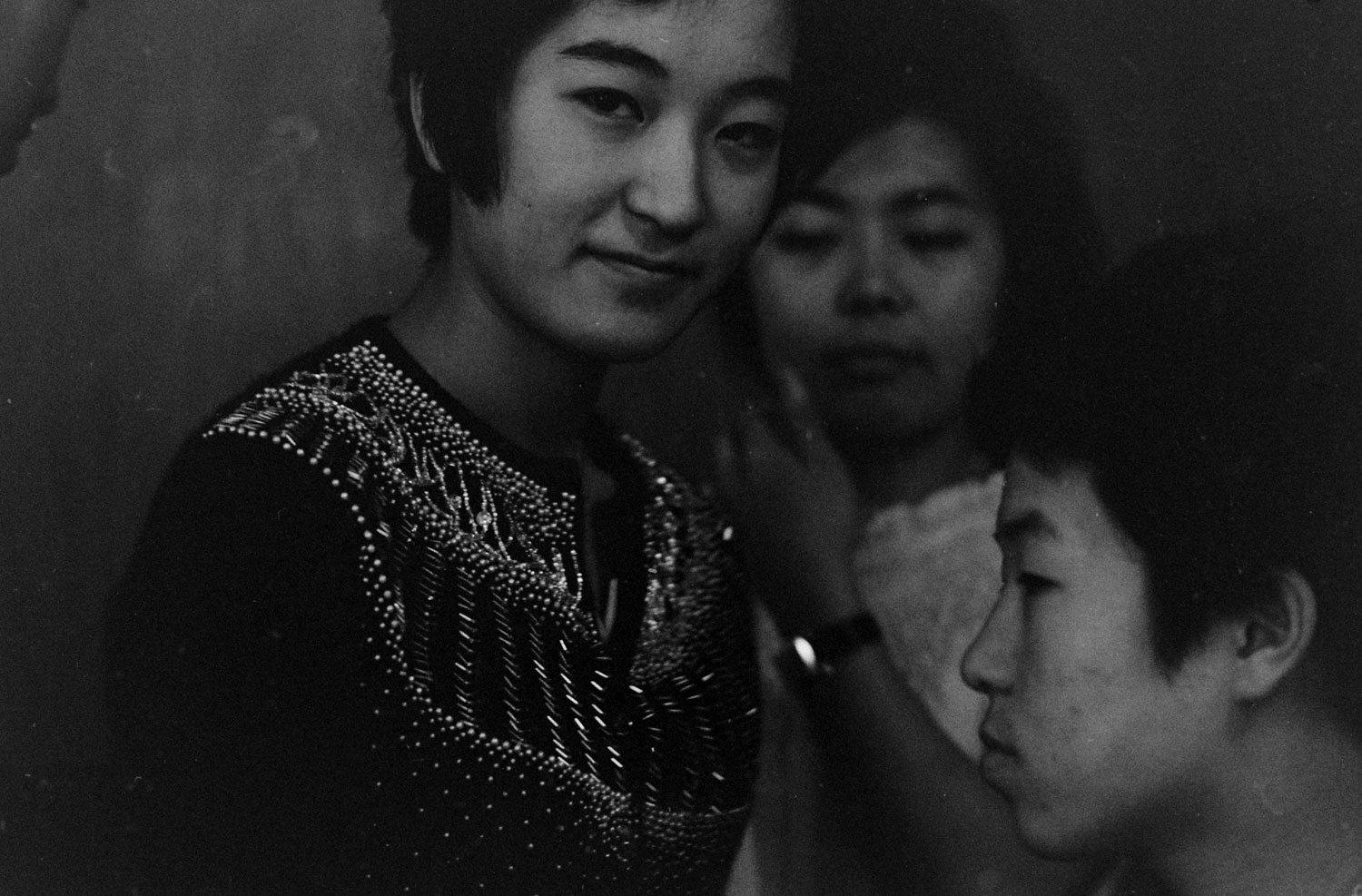

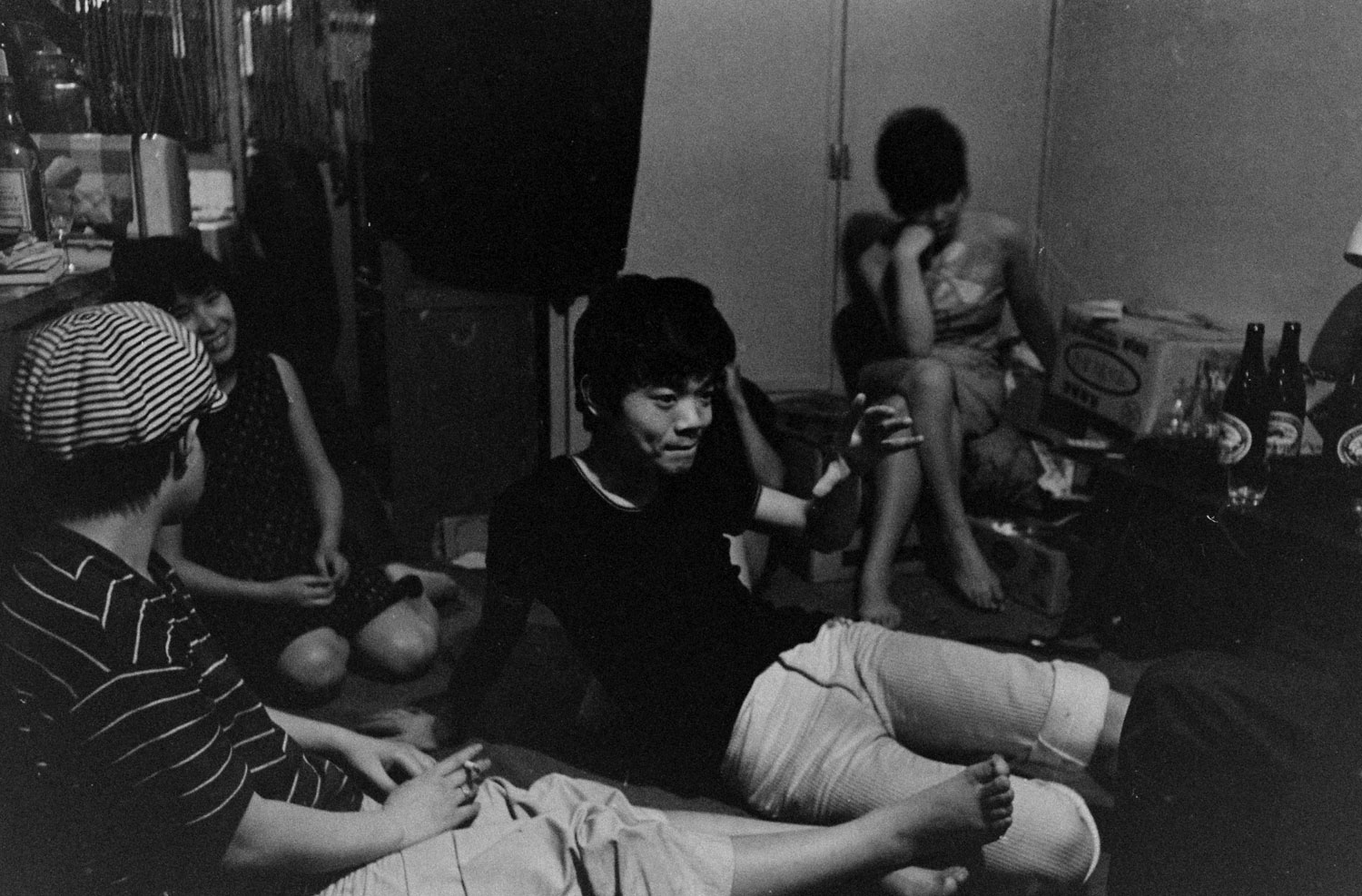

Having sliced the ties that bind them to the home, in desperation they form their own miniature societies with rules of their own. The young people in these groups are are bound to one another not out of mutual affection — in many cases the “lost ones” are incapable of affection — but from the need to belong, to be part of something.

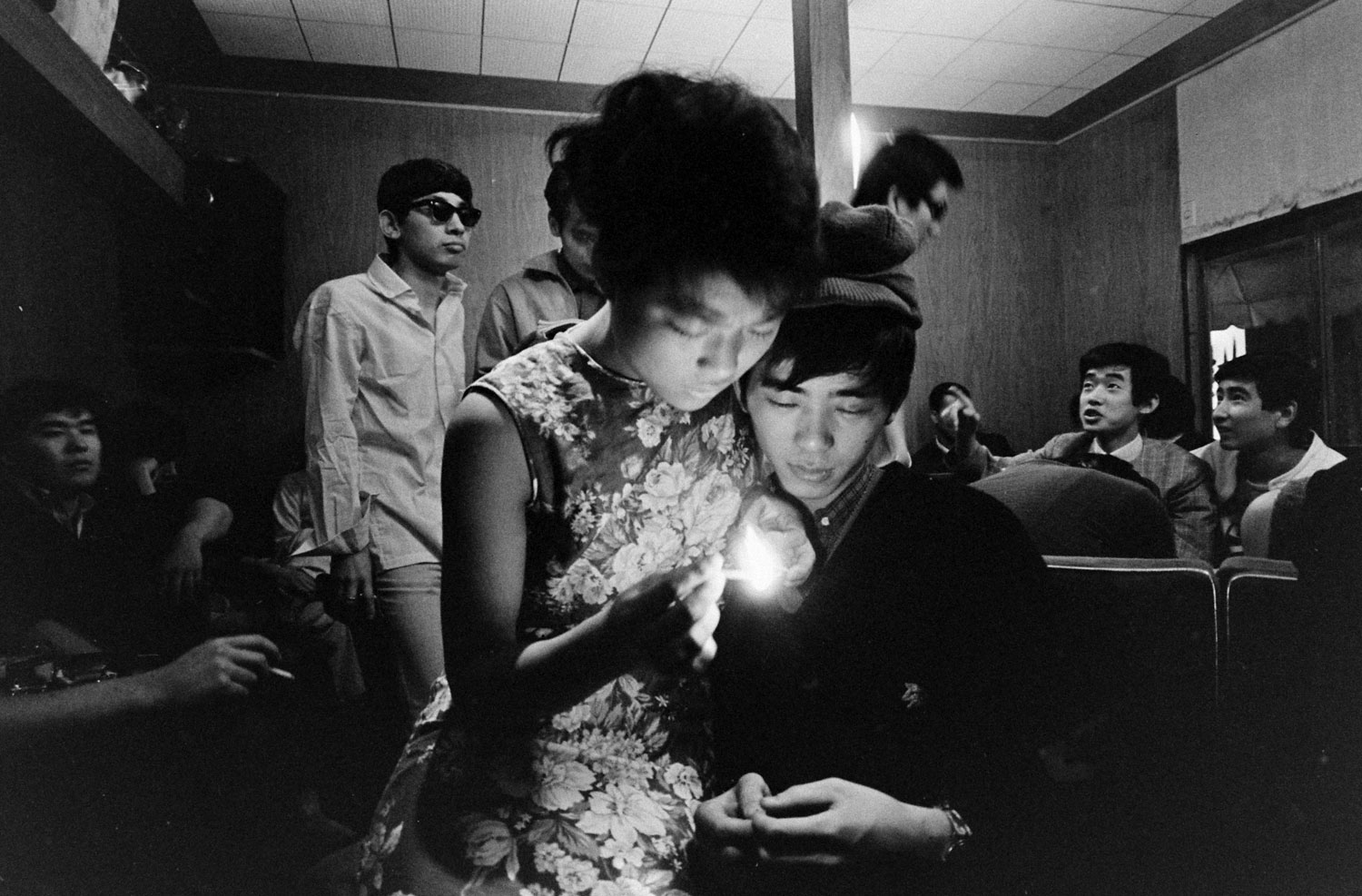

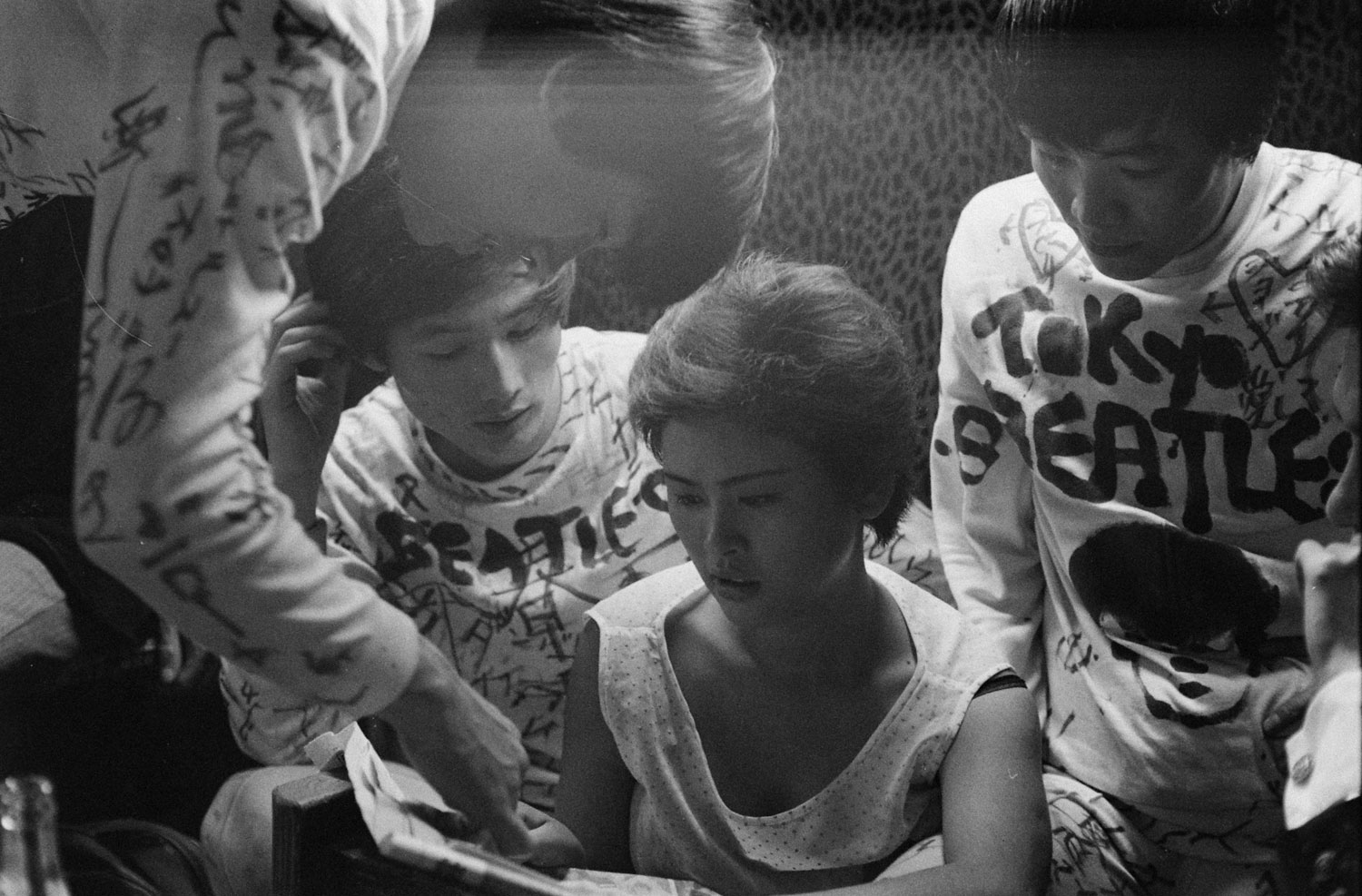

Both the article in LIFE and the story told in Morse’s ruminative — and, in some ways, far more devastating — notes make clear that this “lost generation” was not even remotely monolithic. While they might, to varying degrees, have shared a genuinely nihilistic outlook toward their own and their country’s future, the runaways, rock and roll fanatics (the “monkey-dance, Beatles set,” Morse calls them), pill-poppers, “motorcycle kids” and innumerable other subsets of Japan’s youth-driven subculture attest to the breadth and depth of teen disaffection to be found virtually anywhere one looked in 1964 Tokyo.

That Michael Rougier, meanwhile, was able to so compassionately portray not only that disaffection, but also captured moments of genuine fellowship and even a fleeting sort of joy among these desperately searching teens, attests to the man’s talent and his dedication to share the story of what he saw.

— Ben Cosgrove is the Editor of LIFE.com

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk.

![115039731.jpg [Yoko] often ends her long nights sprawled on a futon in a friend's room."](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/japanese-youth-25.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![115028026.jpg "Sometimes [Yoko] goes down to the port in Yokohama to watch the ships sail off to the places she only wishes she cold go. At sunset, her 'day' begins again."](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/japanese-youth-30.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com