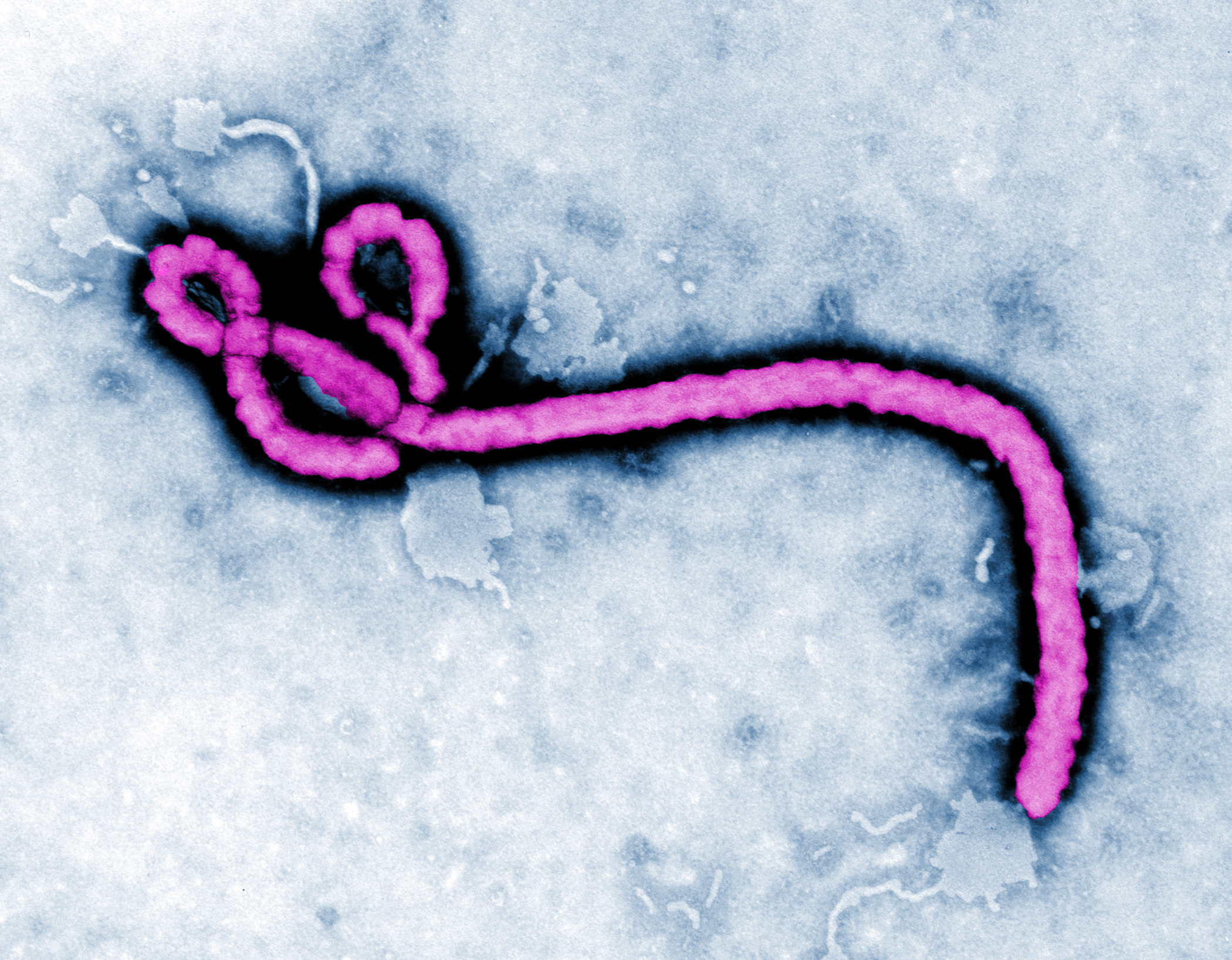

The tragic journey of Ebola victim Thomas Eric Duncan from Liberia to Texas, where he died at the hospital that initially sent him home undiagnosed, revealed gaps in the screening and preparedness system aimed at detecting Ebola cases. However, no one foresaw how that system could be porous enough to allow a disease carrier to pass undetected from the West Africa Ebola zone to the suburbs of Dallas. Nor did anyone foresee how his missed diagnosis worsened matters by allowing his infection to intensify further.

Ironically, by escaping Liberia’s overwhelmed hospitals and in reaching Dallas, Duncan found himself in a land where his illness could be fought using modern intensive care, including access to an experimental drug. His sickness resulted in quarantines for those who came in contact with him, stoked fears within the community in which he lived ever so briefly, and forced a realization that Ebola could pop up anywhere within a country.

Even more cases like his could be forthcoming.

As the epidemic accelerates, a new onrush may emerge of West African “Ebola refugees” fleeing their homelands’ increasingly hellish conditions. Duncan’s success in reaching America and getting advanced health care may spur others to flee if economies and living conditions collapse further. Others who interacted with active Ebola victims and those who believe themselves infected might evade travel restrictions en masse in order to reach foreign lands with better health care.

With more people falling ill and infecting others, the number of symptom-free carriers there will escalate rapidly. Because Ebola can incubate symptom-free for up to 2-3 weeks, present control measures may not be able to detect those harboring the virus as they board planes or arrive at customs halls. Such controls are keyed to active symptoms, such as fever or bleeding, and will miss those who are symptom-free.

A further vulnerability is the reliance on travelers’ self-reporting of past contacts with Ebola victims. But unknowing or desperate people may misstate their past contact status, and if they are not exhibiting active symptoms even upon questioning, then chances are that they would be allowed to progress to their destinations.

If more asymptomatic Ebola carriers reach industrialized countries, those nations’ medical preparedness will be tested if and when they become sick. In spite of proclamations of readiness, it is uncertain if all health care sites are ready to detect and treat them. Finding Ebola cases relies upon frontline health workers to recognize key signs, to zero in on travel history, and to act quickly.

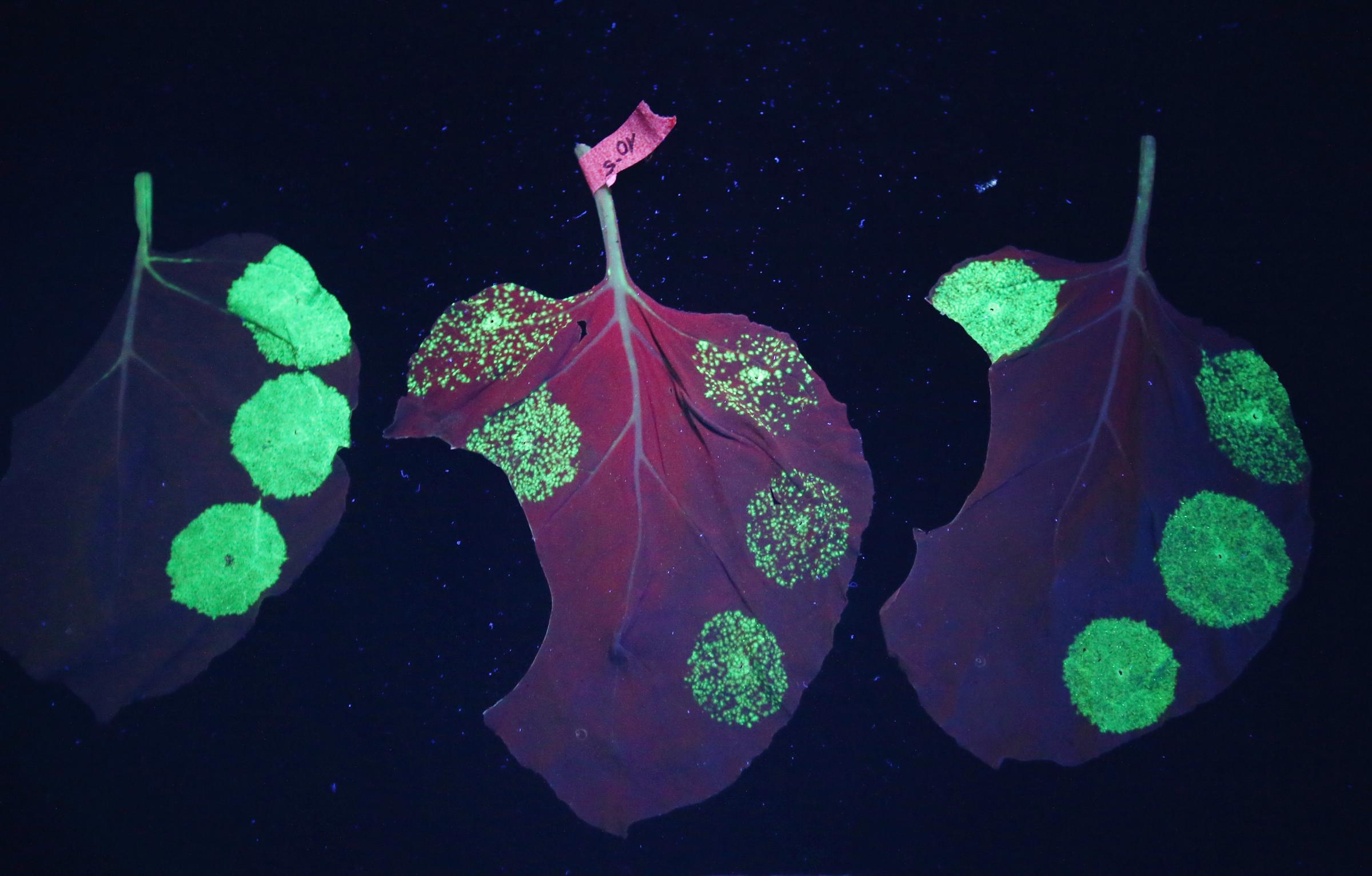

See The Tobacco Leaves That Could Cure Ebola

But health workers already complain of lack of training and protective equipment, and the myriads of health facilities nationwide with wide variations of staffing, equipment, and physical layout complicate planning. Our sophisticated, high volume hospitals have an unintended liability: Risks are raised that patients presenting with the true signs of Ebola, which can mimic other illnesses, can slip past the attention of harried or undertrained health workers.

To date, no strict travel bans are expected to be imposed on those leaving West Africa as a result of the Texas case. Officials believe that doing so may inadvertently worsen conditions, and even provoke panic if people try to leave all at once ahead of a complete ban.

Still, the Texas case has stoked rising public and political pressures to bolster travel screening. If new measures are weighed, they should be directed towards the key points of vulnerability in the travel system: departure, en route, arrival, and in the homeland. Airports in the Ebola zone could impose wider screening measures such as temperature checks and individual interviews by a health official to elicit any traveler’s past Ebola exposure.

Passenger manifests could be scrutinized ahead of departures or even while planes are en route. On flights deemed high risk, on-board health marshals could immediately assess any passenger with suspect symptoms, apply protective measures, and inform ground authorities to institute isolating procedures upon landing.

Arriving passengers could receive stickers on the back of their passports with a toll free number to call should they suspect onset of Ebola consistent symptoms along with a short list of such symptoms. Calls to that number would alert authorities to potential cases and give them an opportunity to direct the sick to the closest, well-equipped hospital for evaluation. Isolation beds kept in reserve at the hospitals close to airports would give screeners ability to quickly send patients for evaluation.

Domestically, we can begin special stress testing of hospital responsiveness. Simulated patients can be deployed who, with the prior knowledge and approval of authorities, present themselves into emergency rooms and imitate symptoms of Ebola. Different test patients could be inserted into clinics who present in a variety of ways -—from overt, classical signs to more subtle and challenging presentations. Staff reactions to these “mystery patients” can be gauged and evaluated, and weaknesses identified and overcome.

Another tactic is to conduct preplanned Ebola exercises, similar to disaster response drills, that activate the entire hospital staff and are coordinated with public health authorities. Publicity of these exercises raises community awareness and boosts citizens’ confidence that local authorities are taking the threat of Ebola seriously. Lessons learned would enhance readiness by flagging shortcomings so they could be overcome.

If the epidemic intensifies, we should prepare for the possibility of an influx of Ebola refugees who, upon gaining entry, could become ill in any locale, putting many more at risk. Thus we need to re-think the Ebola defense zone to go beyond hard hit West Africa to include the world’s transport links and major destinations in the American homeland. With fears rising, readiness should go beyond pronouncements of readiness to involve both a rapid upgrade of screening measures along travel corridors and the initiation of stress testing of hospitals and clinics.

Jack C. Chow, M.D. is a former U.S. ambassador on HIV/AIDS and global health (2001-2003) and a former assistant director-general of the World Health Organization on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria (2003-2005). He is currently a professor of global health at Carnegie Mellon University’s Heinz College of Public Policy, and based in Washington D.C.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com