Not all fats we eat are created equal. We all know that, trying to dodge the less healthy ones that come from animals and dairy products and load up on those less likely to clog our arteries and add to our waistlines.

But it turns out that even after we consume fat, we store it in different forms as well, and scientists reporting in the journal Cell have identified a pathway in the brain that can direct our bodies to convert stubborn waistline-growing fat into a different fat that’s easier to burn off.

MORE: Having The Right Kind of Fat Can Protect Against Diabetes, Study Says

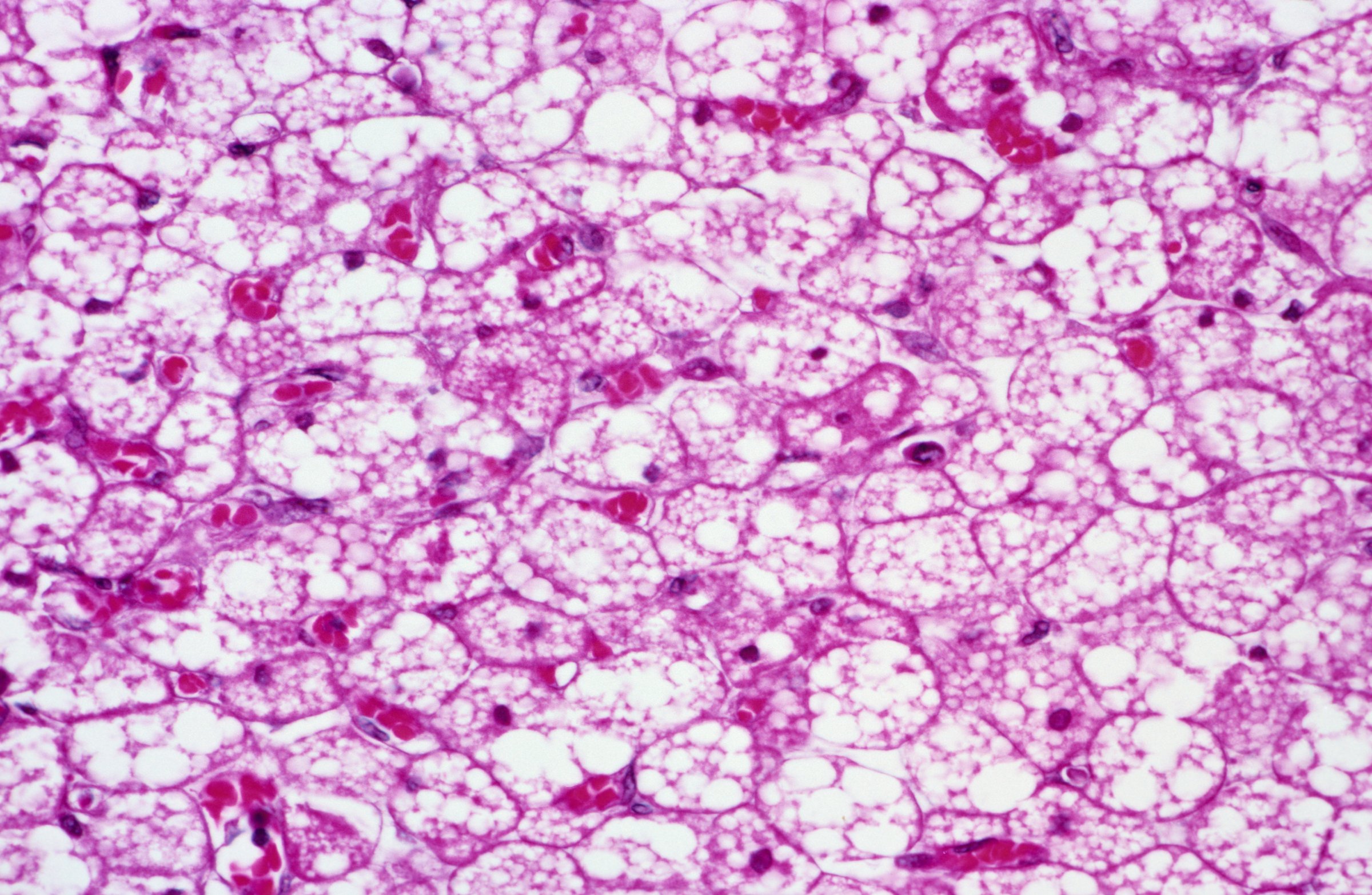

Brown fat, so-called because it is rich in the darker hued energy factories of cells known as mitochondria, is a calorie-hungry machine. It consumes a lot of energy and generates just as much, mostly in the form of heat. That’s why brown fat is more common in newborns, who need to be protected from getting chilled after nine months in the toasty womb. As we age and are better able to regulate our body temperature, we lose brown fat, and until recently scientists thought most adults had little brown fat, if any.

Now researchers at Yale School of Medicine have identified the process that turns white fat, the more common kind in the average adult body and the primary culprit in weight gain, into the energy-consuming brown fat.

QUIZ: Should You Eat This or That?

MORE: How Now, Brown Fat? Scientists Are Onto a New Way to Lose Weight

Working with mice, the scientists honed in on a set of neurons in the brain that regulate the body’s energy balance, including the breakdown of glucose, which is the primary source of fuel for most cells. When mice fast, for example, their bodies shift into a type of emergency mode, conserving energy and shutting off systems and cells that require high amounts of energy, such as the heat-generating brown fat cells. Fasting resembles times of starvation, so evolutionarily, this makes sense; when food is scarce, the body shunts its energy toward essential processes, such as keeping the heart pumping and getting oxygen to the brain.

Xiaoyong Yang, an associate professor of comparative medicine and physiology at Yale, showed that this switch to conserve energy is intimately tied to hunger signals in the brain. “We showed that hunger itself is a signal that controls the browning of white fat, so the brain can actually control the browning of white fat.”

That means it’s the brain that regulates what type of fat, and how much of it, is burned. In obese animals, Yang found, these hunger signals are dysfunction; overweight and obese mice eat regardless of whether they are hungry, so the normal physical signals from the stomach don’t function properly. Heavier animals continuously feel hungry, even if they’ve eaten enough for their energy needs. That perpetuates the cycle of obesity, since it shuts off the transformation of white fat into energy-consuming brown fat, and therefore keeps more fat in an inert, pound-packing form.

“Obese animals, and people, lose the response to hunger,” he says. “Although there is plenty of food and plenty of energy, the hunger neurons send a false message that the body needs to conserve energy, not burn it.”

Eventually, he says, it might be possible to intervene with the hunger signal anywhere along its journey from the brain to the fat cells, and that may shift the balance in favor of burning fat rather than storing it, which might open the door to weight loss. But calibrating the switch will be critical, since favoring the burning of fat can also lead to other physiological problems such as wasting and malnutrition. “You don’t want to set the body’s energy balance to zero,” says Yang. “You want to reset it to normal levels.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com