As college students settle into the fall semester, they are probably worried about whether they’ll get along with their roommates, and how they’ll fare in Organic Chemistry—and probably (along with their parents) about sexual assault. Recent media reports have exposed terrifying stories amidst heightened scrutiny of the Department of Education, which is currently investigating 55 schools’ administrative responses to sexual assault on their campus.

And those students (along with their parents) are right to worry: it’s during these first weeks on campus that sexual assault rates are highest. Right now is called the “Red Zone” – it refers to those beginning of the year parties where young women are eager to please and young men have a lot to prove, where alcohol is flowing freely, and everyone is eager to break out of their helicopter parents’ ambit. The atmosphere is steamy and soggy, peering out from behind beer goggles makes nearly everyone’s vision blurry. Words like “consent” and “resistance” lose precision.

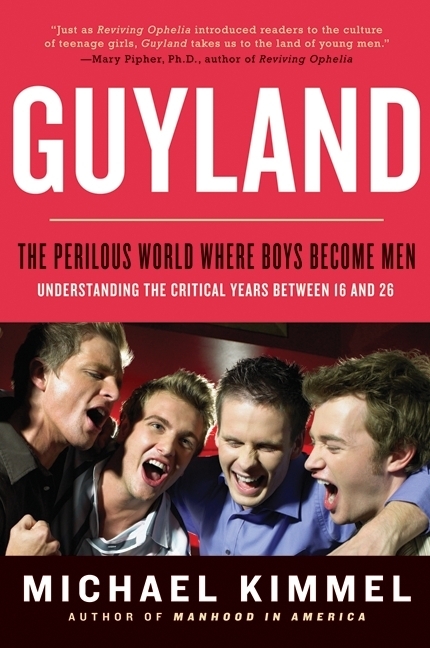

At least that’s the prevailing idea. But lets look a little more closely at those parties. While researching my book, Guyland: The Perilous World Where Boys Become Men, I probably spent more time as a grown-up observer at these parties than I ever did as a student. On the surface, it looks pretty equal: guys and girls having fun, drinking themselves silly, dancing as long as they can stand up (or sometimes beyond). But many campus parties are arenas of dramatic gender inequality.

This is pretty ironic, because during the day, there is probably no institution in America that is more gender equal. At night, well, not so much. Take a look at how everyone’s dressed. It is a sociological axiom that you can observe dynamics of inequality by looking at who dresses up for whom: Those with less power almost invariably dress up for those who have more. So, by day, in class, women and men dress pretty much the same: t-shirts, sweatshirts, jeans and running shoes or flip-flops. At parties, though, the guys will still be dressed that way, while the women will be sporting party dresses, high heels and make up.

And just who is hosting the parties? Did you know that national Greek-letter sororities are prohibited from serving alcohol at parties? Fraternities, by contrast, are permitted to do so (in accordance with state alcohol laws). The Interfraternity Council has no national policy, but focuses instead on vague advice on alcohol education.

Thus the frats hold the parties. Walk up to the door and there are always a few brothers who act as gatekeepers, admitting those women who appear to dress, drink, dance, and party in the ways that the fraternity guys most want, and excluding those who don’t.

Let’s be clear: Sexual assaults take place at all hours of the day and night, in every location on campus, including dorms, classrooms, libraries, and off-campus residences. But the fraternity party has been singled out for special attention, not because fraternity men are more likely to be sexual predators, but because the research makes clear that fraternity parties are, to be blunt, the most likely site for sexual assault to occur.

So, at a time when 55 colleges and universities are being investigated over how they handle claims of sexual assault, a first step might be to simply reverse this alcohol policy.

Imagine if, just for 2014-2015, only sororities were permitted to serve alcohol at the parties (in accordance with state law) and fraternities were expressly prohibited from doing so. Now party gatekeepers would be the sorority sisters who will determine if the men who seek entry are dressed well enough, behaved well enough, and responsible enough to be there.

Of course, it would be impossible for the sisters to prevent sweet looking nicely dressed predators from entry. But policing doesn’t have to stop at the door. Act like a jerk? The women will ask you to leave. Resist, and that’s where the legions of men who complain that they, the “good guys,” are unfairly tarnished with such broad brushes come in. Eager to show the women they are, in fact, good guys, they show the lout the door, and burnish their reputation – and get invited back.

At fraternity parties, when a young woman is so drunk she can barely stand up, some enterprising young predator will try to take her upstairs. Where will he go at the sorority party? Some will ask their friends “can I use your room?” And just as surely, some women will say yes. But others will be alerted, and assault would be far less likely.

It has the drawback of throwing the burden of preventing sexual assault back on women, who’d have to staff, police, and procure for the parties, and clean up the messes afterwards. But I suspect most women would happily trade Sunday morning cleanups for a lower likelihood of sexual assault. And guys wouldn’t exactly be prohibited from helping out.

This simple change will not eliminate sexual assault on our nation’s campuses. Nor, however, will strategies that focus only on changing individual behavior. It’s a start, and it can accomplish two things, one concrete and one abstract. It will reduce assault by reducing opportunity, increasing peer surveillance, and leading young men to think before they act. And abstractly, it begins a conversation about the causes of sexual assault on campus, and that there need to be both institutional and individual responses.

Let’s see just one campus try it for a year and see what happens. Because transforming the “rape culture” will require institutional changes. While you are fighting for your right to party, as the Beastie Boys sang, you shouldn’t also have to fight someone off.

Michael Kimmel, Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Gender Studies at Stony Brook University, is the author of Guyland: The Perilous World Where Boys Become Men.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com