In the dusty shopfront of one of downtown Monrovia’s more desolate side streets, Sam Agyra flips through a fly-specked photo album showing off his custom caskets.

Cake-like confections of pale satin, gold detailing and elaborate wooden scrollwork, his coffins have earned him a well-deserved reputation for beautiful work at a cheap price. In good times he was turning out five handcrafted pine coffins a week. Now? He doesn’t even want to talk about it. Instead he just laughs, the hysterical cackle of a man watching his business of 25 years grind to a halt. He hasn’t sold a coffin in two months, ever since the Liberian government declared, in an effort to tackle the Ebola crisis, that all of the country’s dead should be burned and not buried.

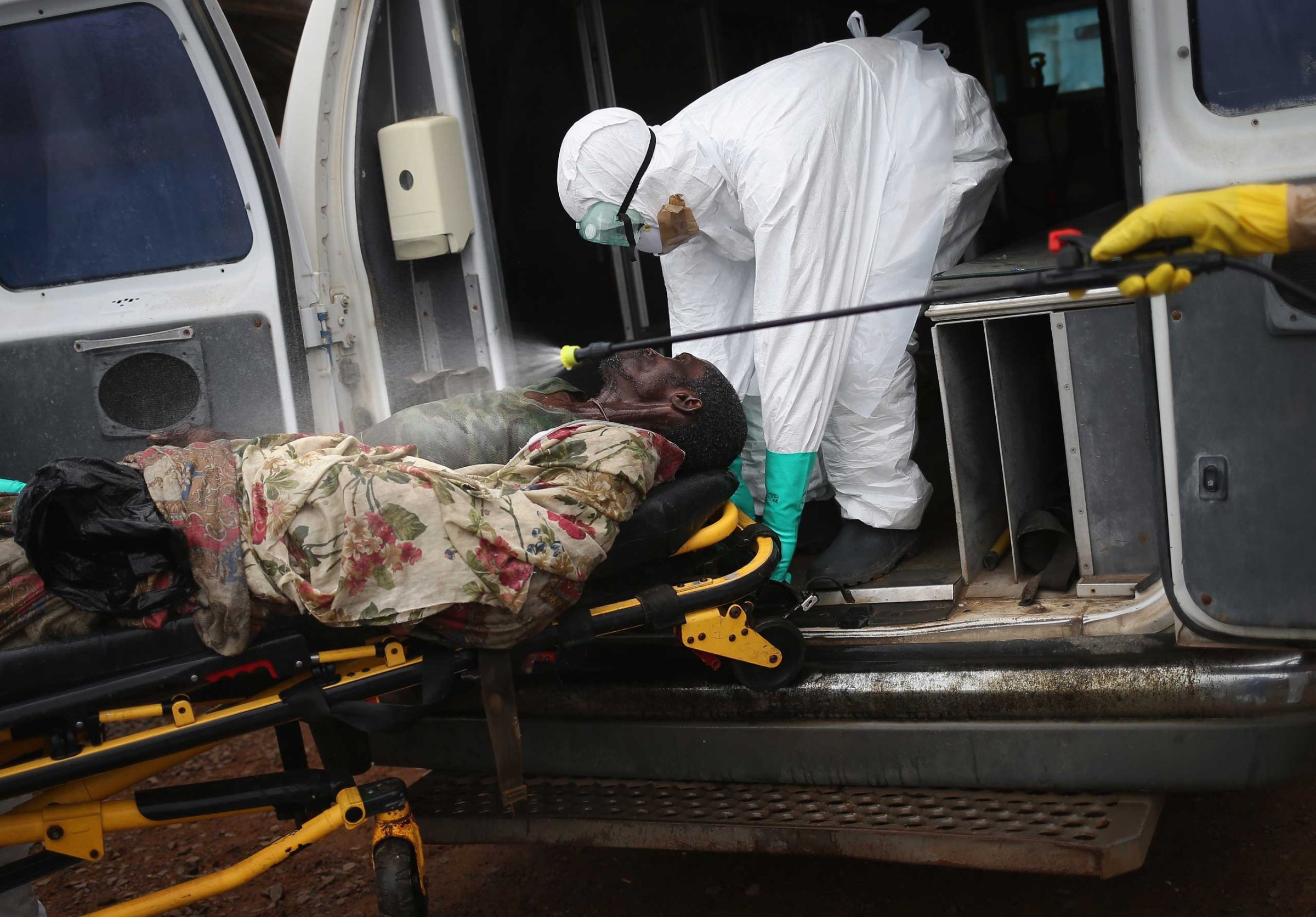

An Ebola victim is most contagious in the moments and days after death, when unprotected contact with infected bodily fluids carries an extremely high risk of transmission. Liberia’s traditional burial practices, in which mourners bathe, dress and even kiss the corpse, are widely credited with the early explosion of Ebola in the country, where over 2,000 have so far died of the disease. Overwhelmed by the increasing number of dead, and faced with community fears that the buried bodies may also transmit the disease—which, if interred properly, they won’t—Liberia’s government declared in August that all those who died of Ebola should be cremated.

With international help and advice, the government established a Dead Body Management program to pick up Ebola’s victims and dispose of them safely. But testing for Ebola is difficult and time consuming. What little testing resources do exist are reserved for the living, says assistant health minister, Tolbert Nyenswah. With hospitals closed and doctors overwhelmed, it is almost impossible to prove that the cause of death is anything but the deadly virus. “These days, if someone dies, it’s Ebola,” says Agyra. “There is no testing, no questions. Just Ebola, and they take the body away. No one has time for coffins.”

The government directive, while logical from an epidemiological aspect, has taken a toll on a society already traumatized by Ebola’s sweep. It denies communities a final farewell, and has led to standoffs with the Dead Body Management teams who must pick up the dead even as the living insist that the cause of death was measles, or stroke, or malaria — anything but Ebola. “We take every body, and burn it,” says Nelson Sayon, who works on one of the teams. Dealing with the living is one of the most difficult aspects of his job, he says, because he knows how important grieving can be. “No one gets their body back, not even the ashes, so there is nothing physical left to mourn.”

Monrovia’s mass cremations, which take place in a rural area far on the outskirts of town, happen at night, to minimize the impact on neighboring communities. For a while the bodies were simply burned in a pile; now they are placed in incinerators donated by an international NGO. There are so many that it can sometimes take all night, says Sayon.

In a country where distrust between the people and the government runs deep, the mass cremations have caused a deeper rift, says Kenneth Martu, a community organizer from the Westpoint area of Monrovia. “In west Africa we don’t cremate bodies at all. So when the government takes away our bodies, and can’t even tell us if they died of Ebola or not, it breeds resentment.” Liberians, he points out, are no strangers to mass casualties: two civil wars, from 1989 to 1996 and 1999 to 2003, saw nearly half a million die. “Even with mass graves, people can bring flowers. They know where to find the dead. But here we don’t even know where the ashes are.”

There are exceptions to the cremation directive. If a family can get a signed death certificate from the Ministry of Health stating that the cause of death was not Ebola, they can take the body to a funeral parlor for embalming and eventual burial. There are even dispensations for those who do die of Ebola; under certain circumstances the dead can be buried in a cemetery, if the Dead Body Management team conducts the preliminary steps of laying the body six feet deep and soaking the next four feet of earth with chlorine solution.

But those dispensations are impossible to get without connections. One recent Saturday, a funeral cortege down one of Monrovia’s main thoroughfares drew questioning comments and glares of resentment from bystanders. “Haven’t seen that in a while,” exclaimed one woman. “Must be related to a minister,” muttered a man.

Considering Liberia’s mounting death toll, it is an irony not lost on coffin-maker Agyra that an enterprise that ordinarily profits from death should be struggling. “You hear of 50, 80, 100 people dying a day here, and the coffin business has never been so bad,” he groans. “This Ebola business. It’s bad for people, and it’s bad for me.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com