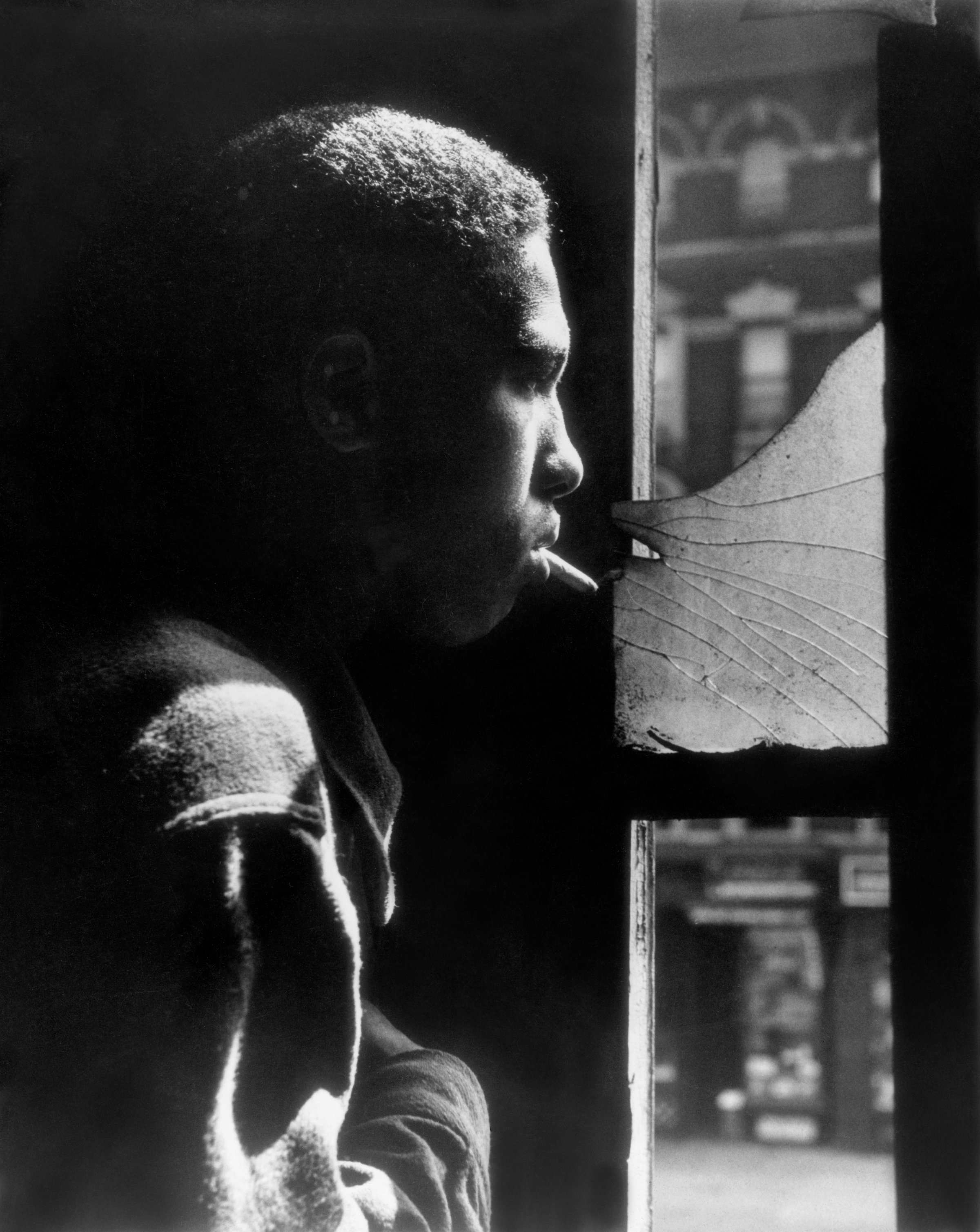

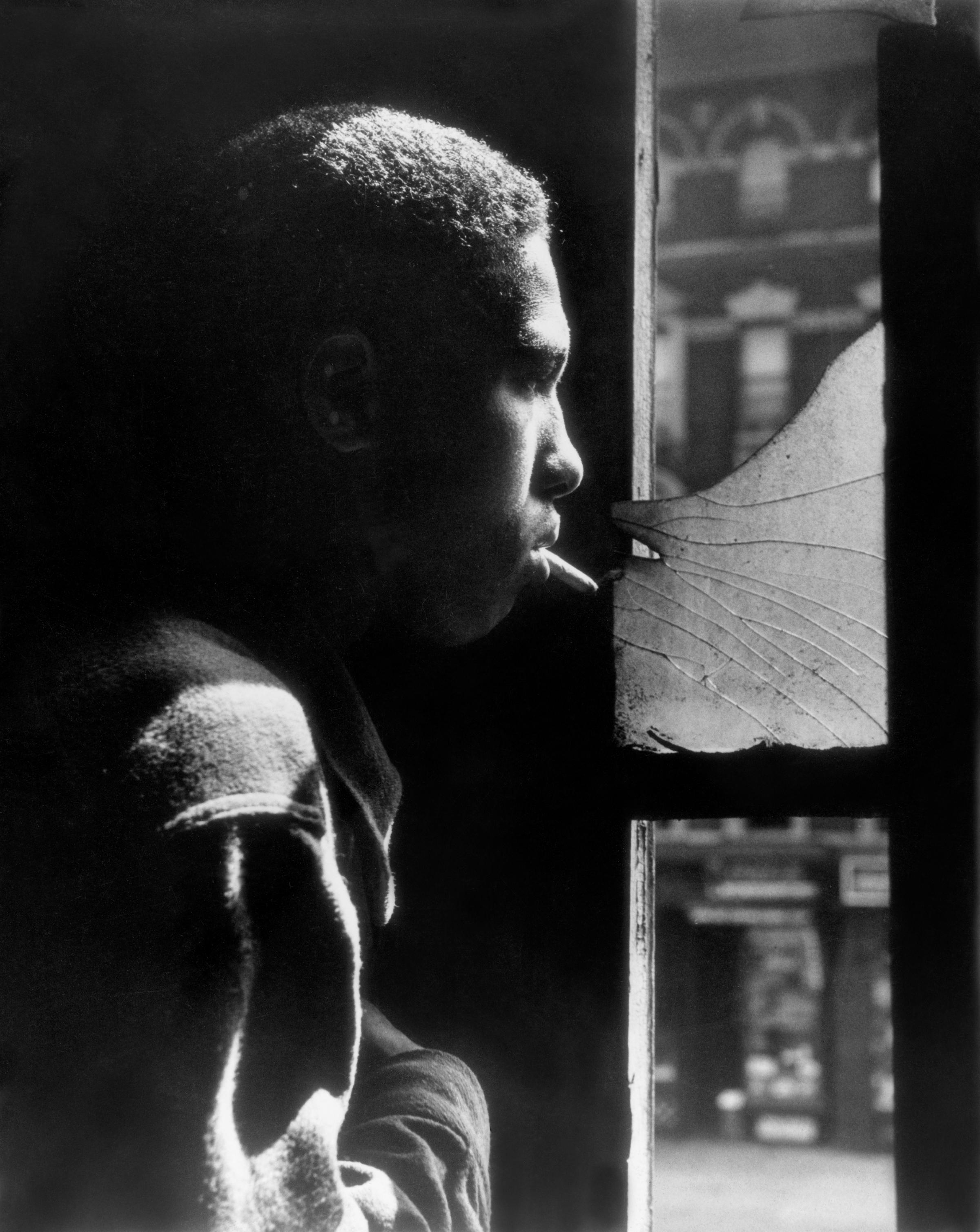

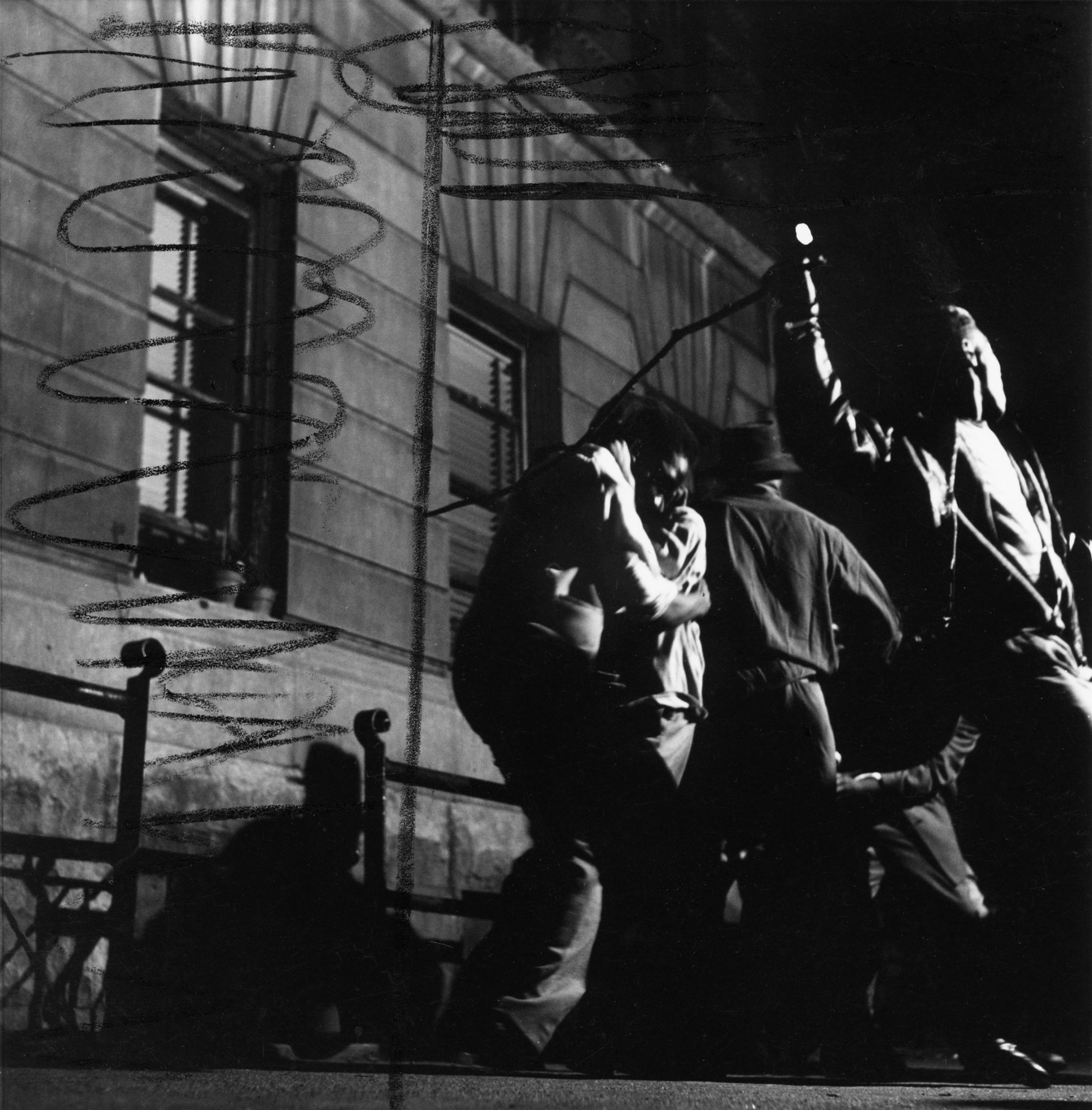

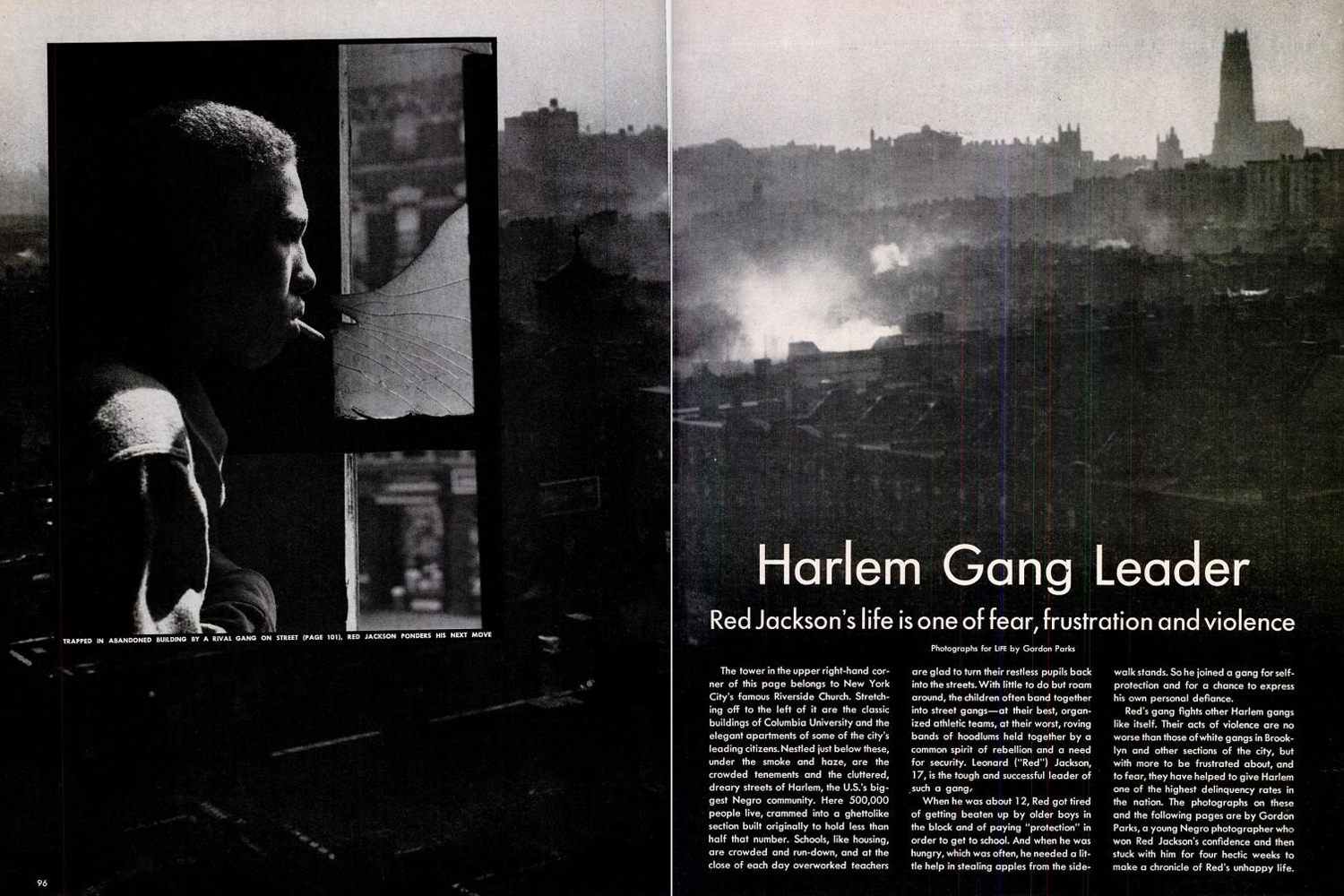

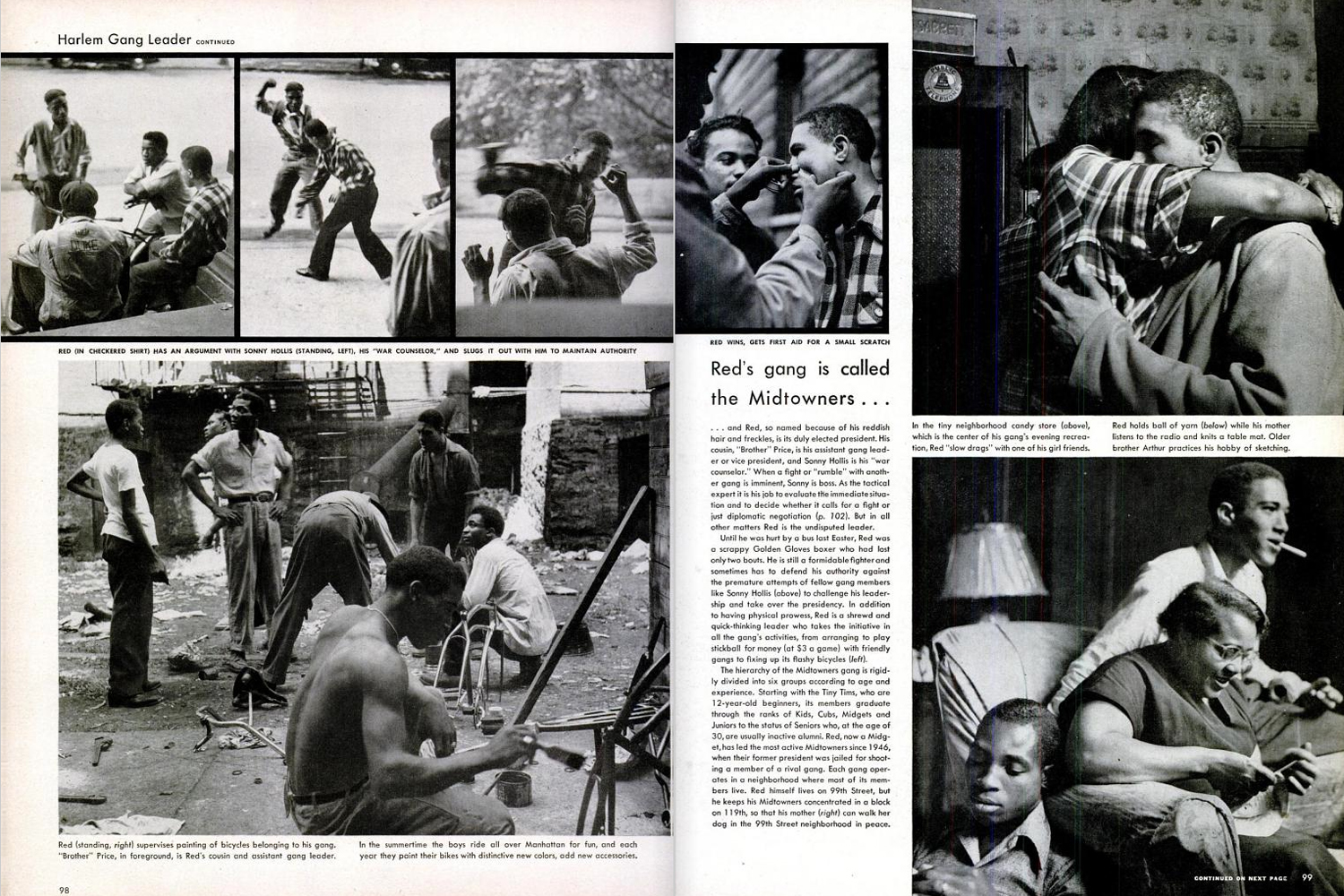

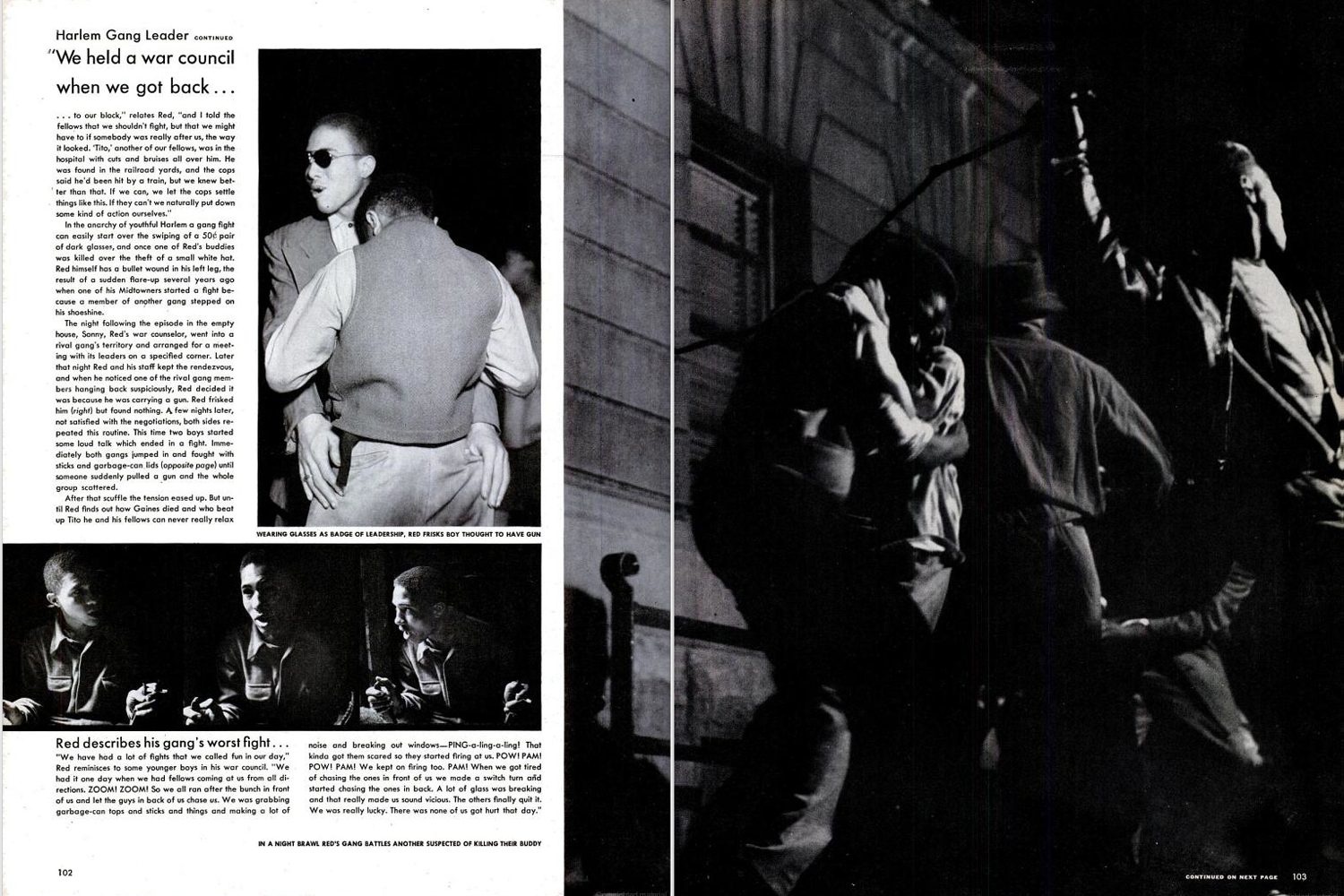

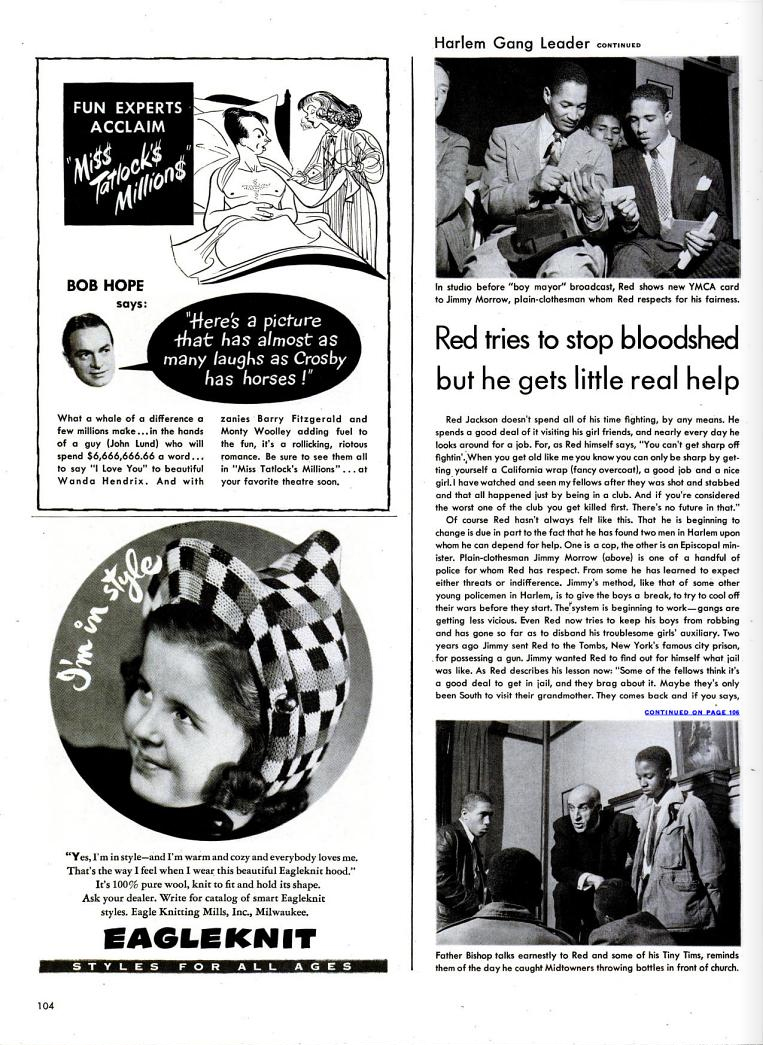

“Harlem Gang Leader” introduced Gordon Parks to America. LIFE magazine, which published the photo essay in its Nov. 1, 1948, issue, had every reason to be proud of the man it called “a young Negro photographer.” He had, it said, spent “four hectic weeks” exploring the world of Red Jackson, the 17-year-old leader of the Midtowners, a gang in Harlem, making hundreds of photographs. Most of the 21 pictures that LIFE’s editors chose for the story evoked the deep shadows and pervasive anxiety of classic film noir. Parks’ field notes provided the raw material for a narrative that mirrored the photographs’ sense of foreboding. The photo essay, while largely compassionate, ultimately depicted Jackson’s existence as one that was shaped by senseless violence and thwarted dreams.

In many ways Parks viewed “Harlem Gang Leader” as a success. Years later, in a memoir, he recalled that “[s]ympathetic letters, along with a few vitriolic ones, poured in” to LIFE’s offices and that Henry Luce, the magazine’s founder, sent him “a congratulatory note.” When Wilson Hicks, LIFE’s longtime photo editor, offered him a position as a staff photographer soon afterwards, he happily accepted, making him the first, and for many years only, African American photographer at the magazine.

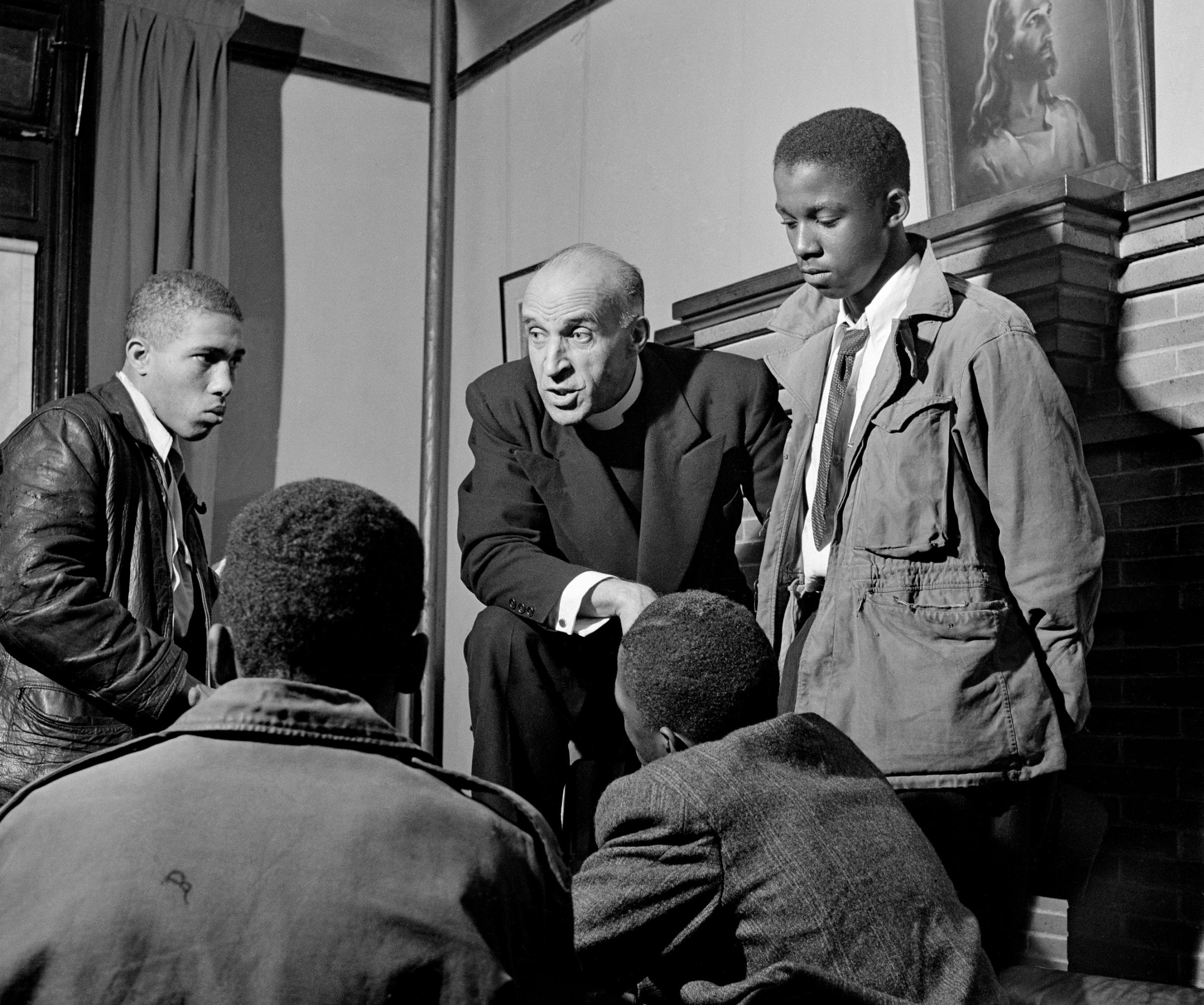

Yet it is unlikely that “Harlem Gang Leader,” with its emphasis on violence and pessimistic conclusion, fulfilled the hopes that Parks brought to the project. In 1946 Ebony, a magazine similar to LIFE that catered to an African American audience, reported that Parks had been looking for an opportunity to work on a photo essay about juvenile delinquency among black youth for some time. He believed that gang members were simply “good, poor kids gone wrong,” Ebony wrote. He felt that if he could “show enough of the kids’ home background on film, he can . . . show the way out of juvenile crime to any social agency which wants to wipe it out.”

A year later Ebony offered Parks the chance to produce a story that was, in effect, a trial run for “Harlem Gang Leader.” (See slides 19 and 20 in the gallery above.) For a photo essay about Harlem’s Northside Testing and Consultation Center, a mental health clinic founded by African American psychologists Mamie and Kenneth Clark, he employed amateur models to create a number of “hypothetical cases” to illustrate the therapy that the clinic offered to troubled youth. Among Parks’ case studies was “Bob,” a young gang leader. A series of photographs showed “Bob’s” transformation under Dr. Kenneth Clark’s care, from a rough gang leader in the first of Parks’ photographs to an obedient son and eager student in the last.

The narrative arc from delinquency to redemption was crucial for Parks. He had lived it. His own impoverished childhood in Kansas, a series of dead-end jobs in Minnesota and a brush with petty crime in Harlem had left him near despair. Photography had been his salvation—and LIFE, his inspiration. Discarded issues of the magazine and a chance encounter with photographer Robert Capa, who often worked for the celebrated weekly, prompted him to buy his first camera. Talent, an enormous capacity for hard work and generous mentors propelled him to a position with the Farm Security Administration’s heralded documentary project, during World War II, and, in the years immediately after the war, to success as a freelance photographer in New York. Vogue, like Ebony, was among his regular employers.

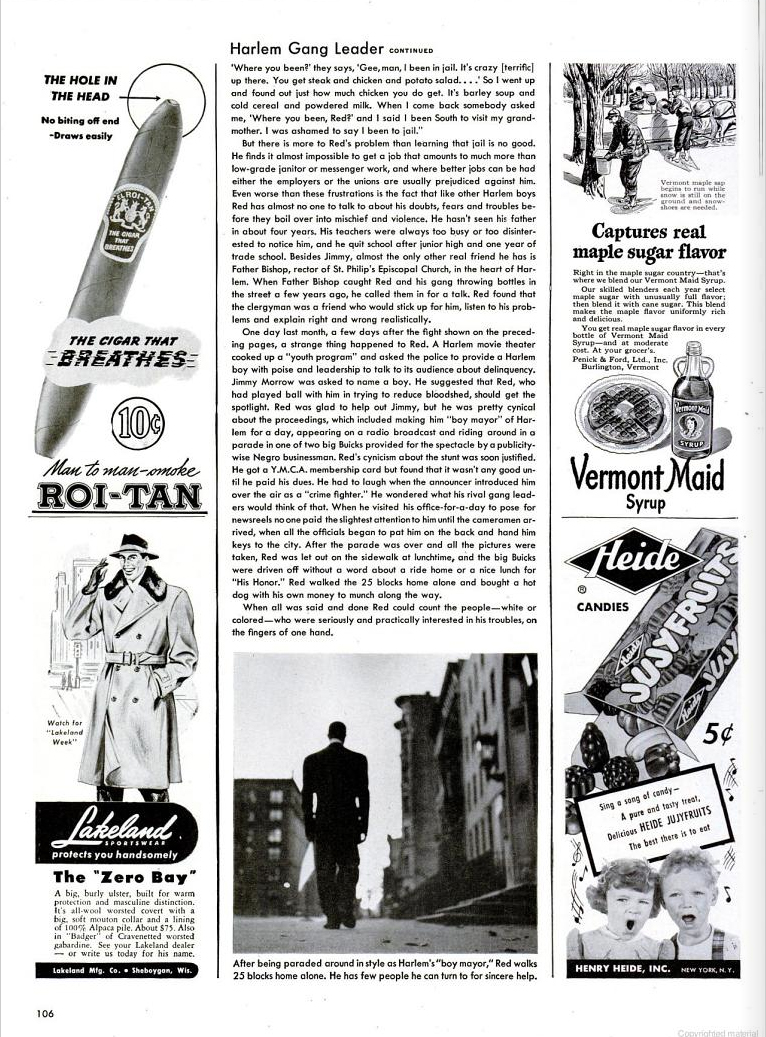

The possibility of redemption is all but missing from “Harlem Gang Leader.” Instead there is a sense of futility. In the photograph that LIFE’s editors chose as the story’s final image, Parks isolated Jackson on an empty Harlem street that stretched far before him into the distance. As Jackson walked away from the camera, tenement buildings, shrouded in shadows, towered above, threatening to engulf him. The story’s closing words reflected the photograph’s gloom. “When all was said and done,” the magazine wrote, “Red could count the people—white or colored—who were seriously and practically interested in his troubles on the fingers of one hand.”

Gordon Parks: The Making of an Argument, which opens on Sept. 19 at the University of Virginia’s Fralin Museum of Art, examines the tension between Parks’ vision of what “Harlem Gang Leader” could have been and the photo essay as LIFE’s editors shaped it. In the exhibition’s catalog, Russell Lord, the show’s original curator at the New Orleans Museum of Art, notes that from the moment Parks turned his exposed film over to LIFE he “had little control over the use (or misuse) and presentation of his pictures.” Editorial decisions resulted in a story that emphasized the “fear, frustration and violence” in what the magazine called Jackson’s “unhappy life.”

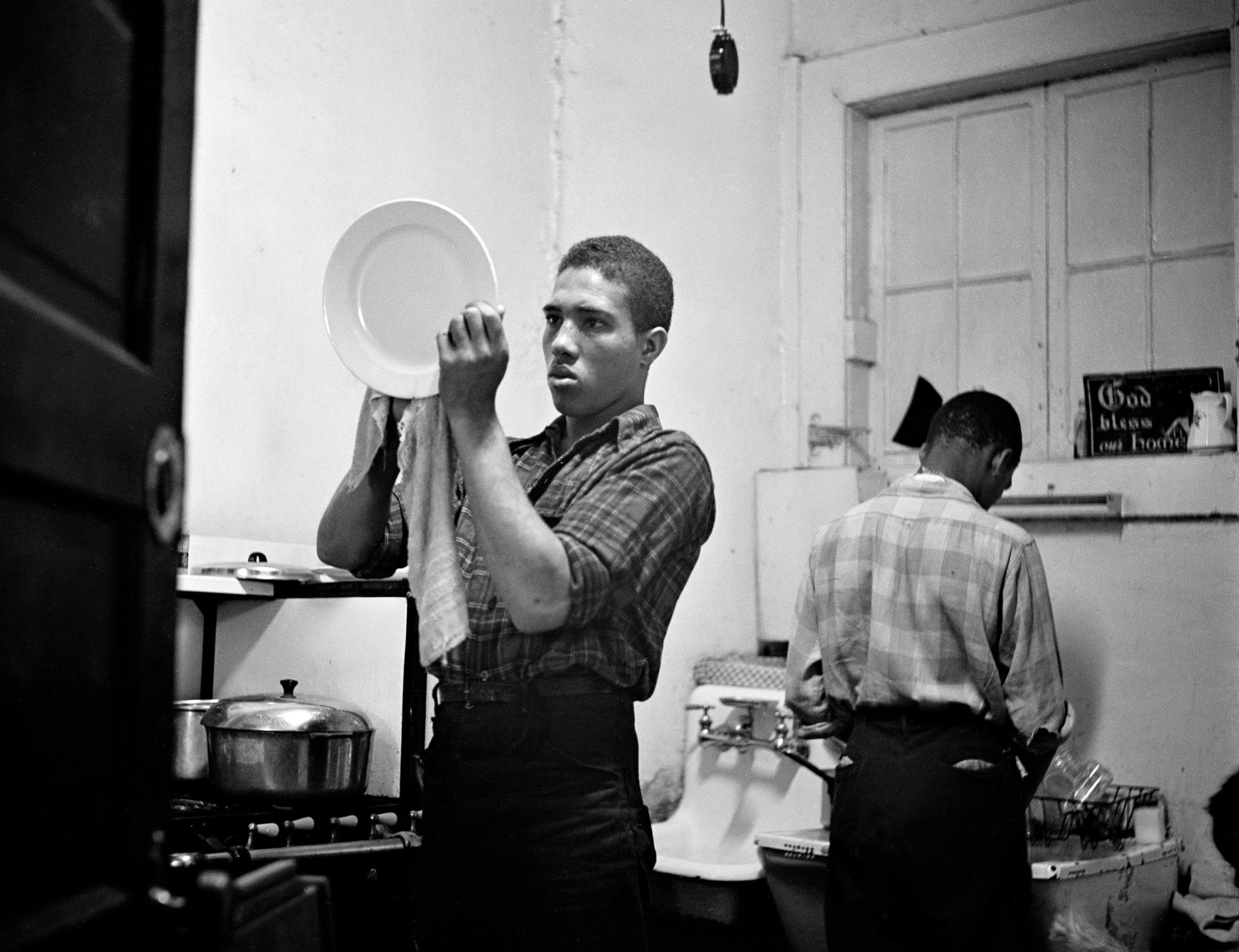

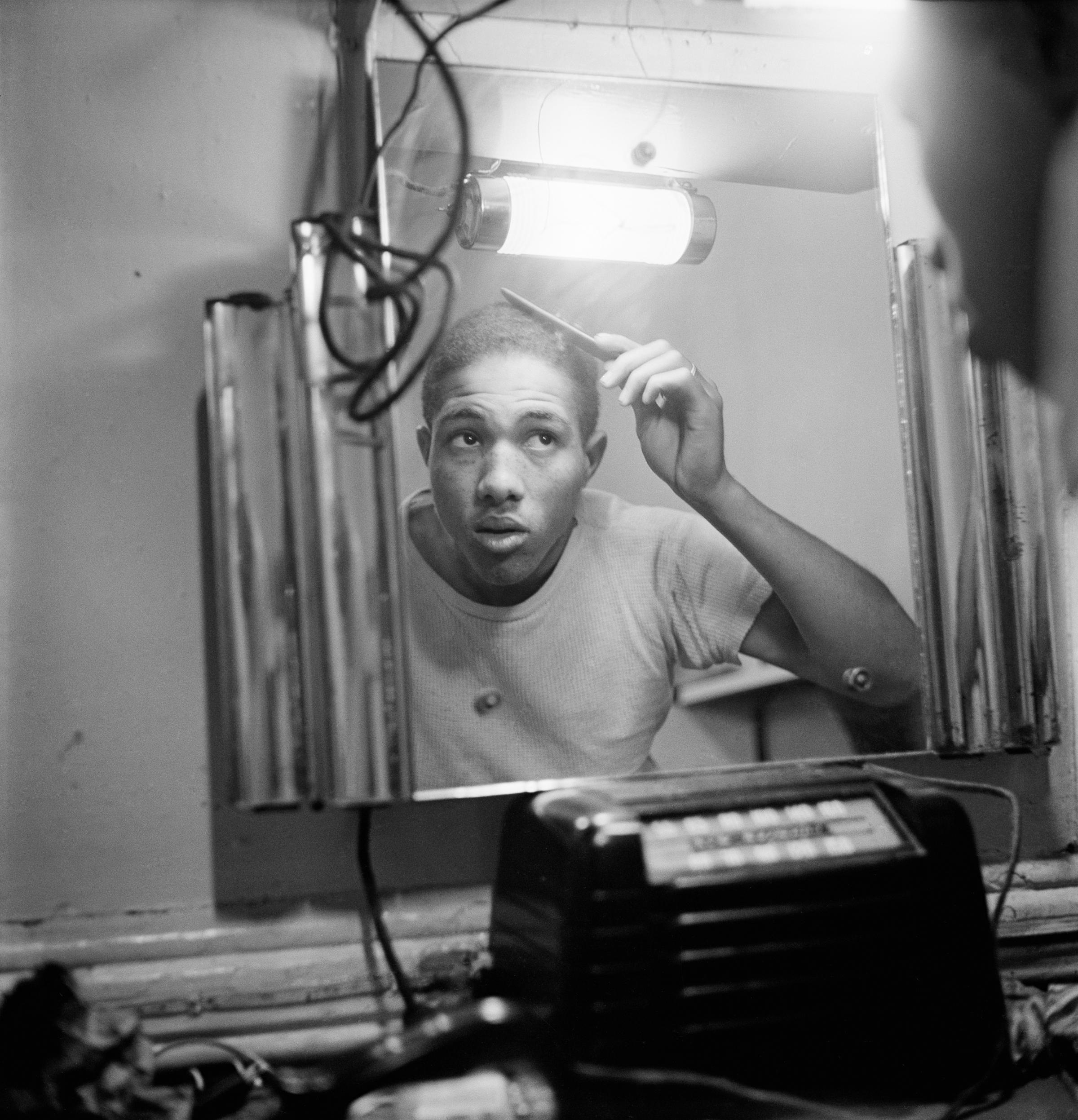

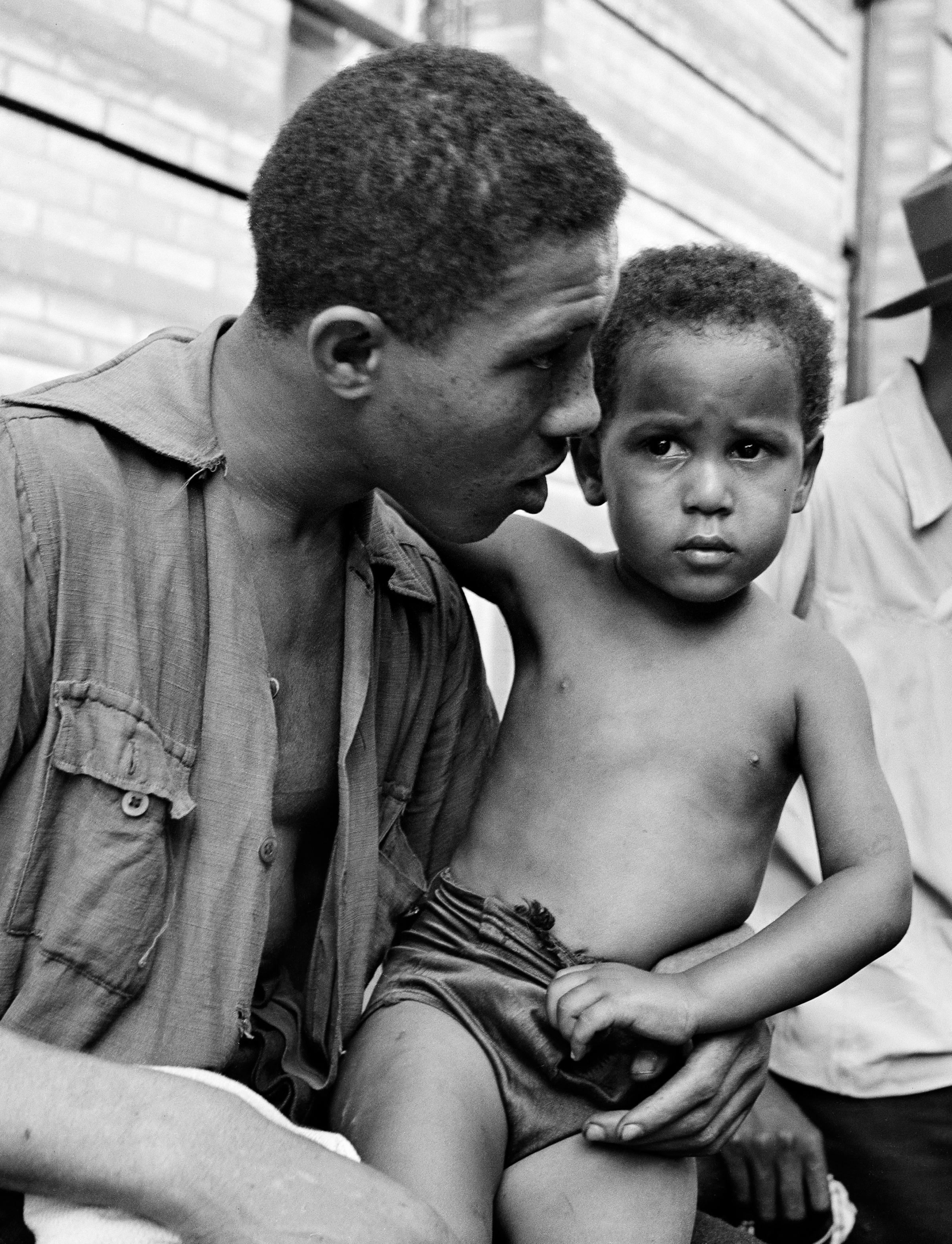

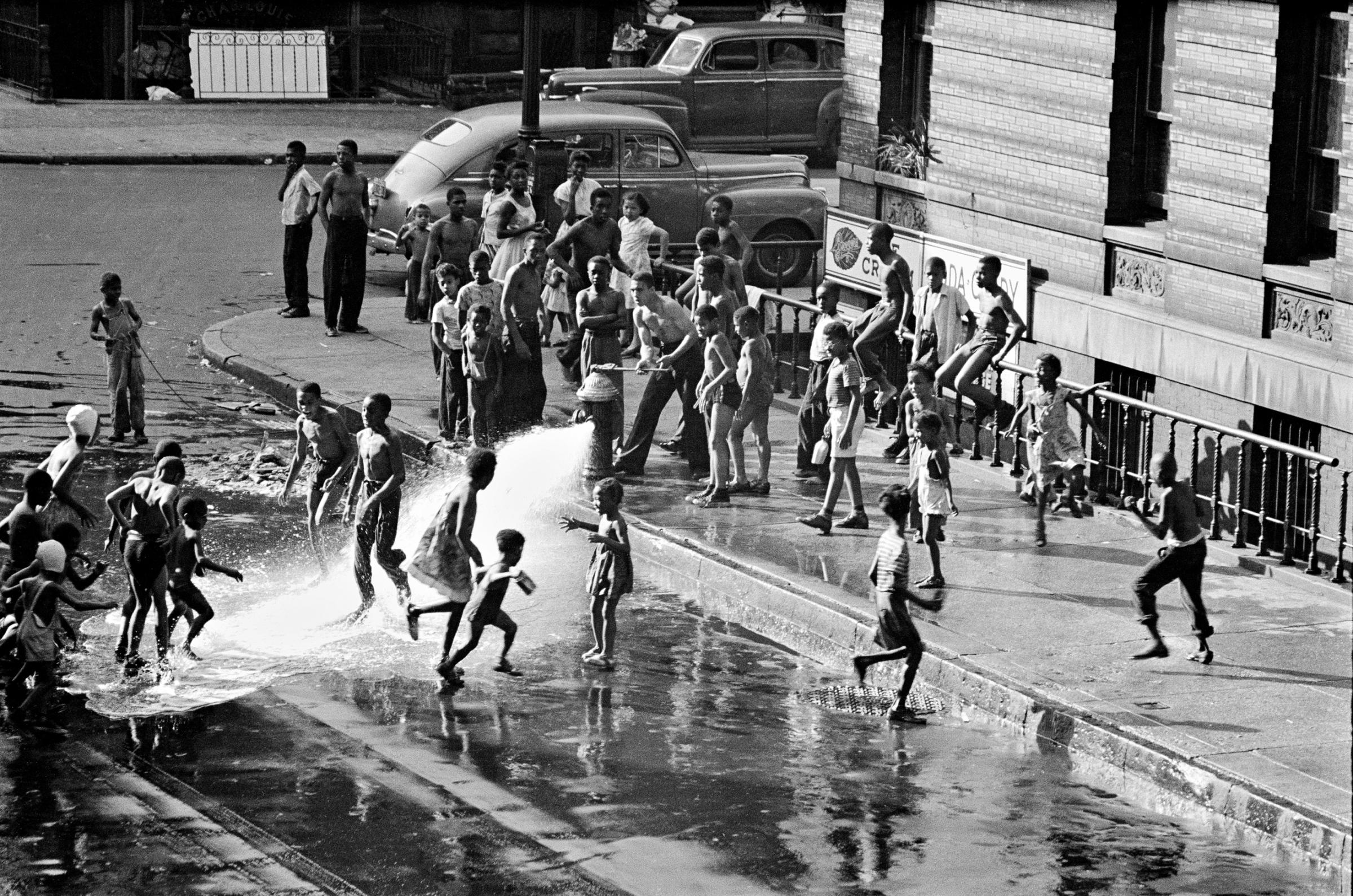

Lord contends, however, that in “the vast collection” of Parks’ “rejected images and out-takes a more complete portrait emerges of Red Jackson as a complex and conflicted teenager.” These photographs, many of which are a part of the exhibition, illustrate that the juvenile delinquent was also a normal teen: opening a fire hydrant on a hot summer’s day so that neighborhood children could cool off in its spray; sweeping the floor of his mother’s apartment; adjusting his tie in front a mirror for a big night out. An alternative photo essay resides, latent, in these pictures, one in which Jackson, like “Bob,” has the potential to leave gang life behind.

The editorial process that created “Harlem Gang Leader” was far from unique. All of LIFE’s photo essays were the products of a collaboration between photographers, editors, writers, layout artists and darkroom technicians. Parks was well aware of the compromises that he would be required to make at LIFE , and he made them willingly. The magazine provided him with a platform that he coveted—one that allowed him to place issues of social justice in front of tens of millions of largely white, middle-class readers. The photo essays that he produced on issues relating to race and poverty during his long career at LIFE made him one of the most significant interpreters of the African American experience in the mid-twentieth century.

Soon after “Harlem Gang Leader” was published, Parks and Jackson lost touch with each other. They did not meet again until a chance encounter on a Harlem street corner when they were both elderly men. Parks gave Jackson his telephone number with instructions to call. By the time Jackson reached out to him, Parks was too infirm to accept visitors. He died shortly afterward, in 2006, at age 93. Jackson attended his funeral.

Red Jackson passed away in 2010. He was 79 years old.

John Edwin Mason teaches African history and the history of photography at the University of Virginia, where he is an associate professor and associate chair of the Corcoran Department of History. Follow him @johnedwinmason.

Gordon Parks: The Making of an Argument opens at the Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia on September 19th, 2014, and will be on view until Dec. 21, 2014.

The exhibition’s catalog, Gordon Parks: The Making of an Argument, is published by Steidl, the Gordon Parks Foundation and the New Orleans Museum of Art and is available from all booksellers.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com