It would be an understatement to call ZMapp a “sought after” drug. Ever since it brough tback two Ebola-infected aid workers from the brink of death, demand for the drug—which has not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and was made available on an emergency use basis—has boomed. The trouble is, there’s no supply.

The doses administered to the U.S. aid workers exhausted a nearly nonexistent supply, according to its manufacturer, Mapp Biopharmaceuticals. But that’s not because it takes a long time to manufacture the antibodies that make up the ZMapp cocktail. ZMapp is taking longer to produce in large quantities because one of the three antibodies in the cocktail doesn’t grow well in the plants—which is how ZMapp is produced.

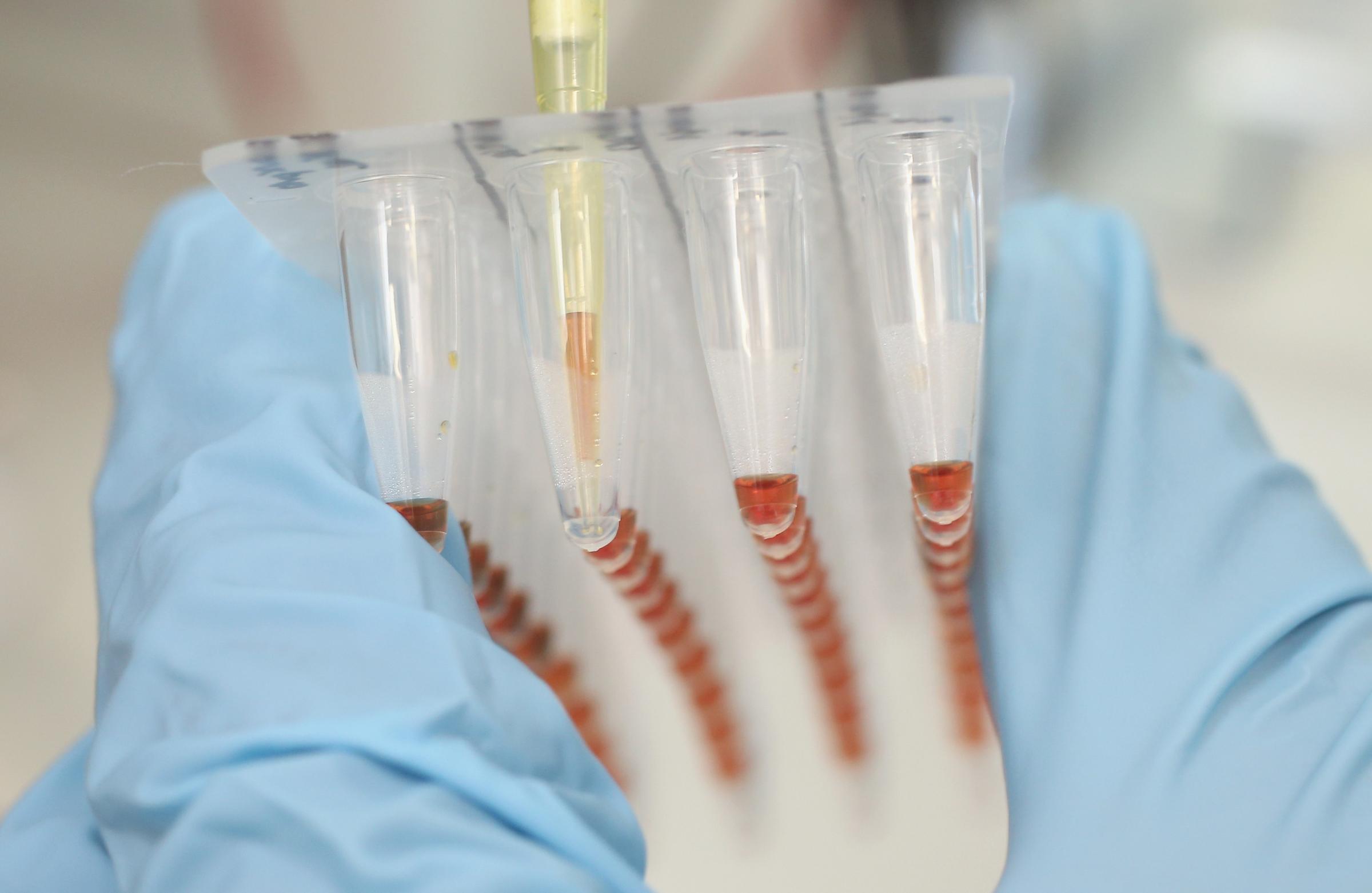

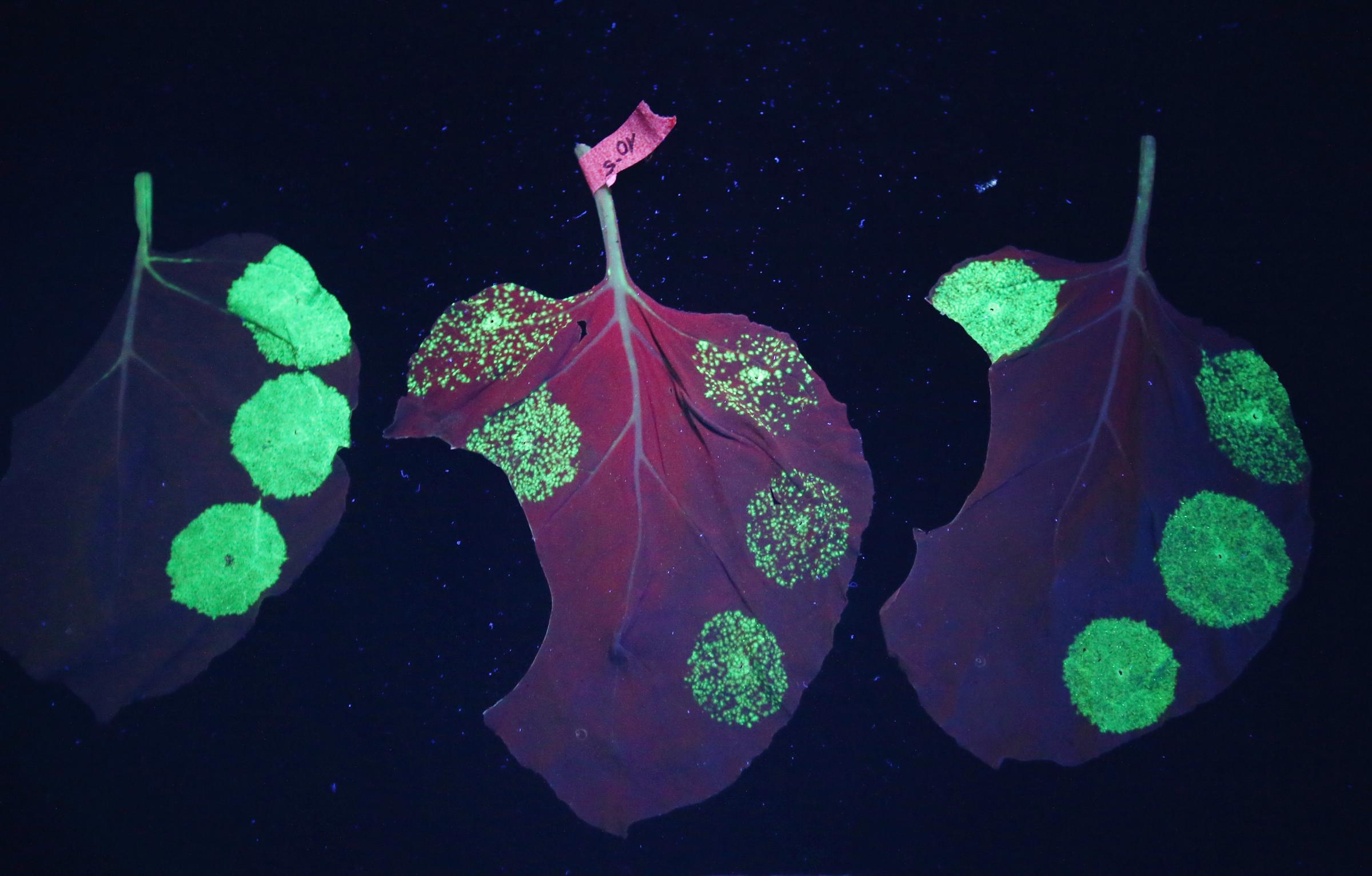

The process involves growing tobacco plants, not in the acres of fields earmarked by tobacco companies for their cigarettes, but in a controlled environment in a greenhouse, for six weeks. Then, the leaves of the plants are injected or infused with a plant bacterium that carries a valuable payload — the genes for the antibodies that can bind to and neutralize the Ebola virus. The plant cells treat the new genes as one of their own, and start making the antibody. It takes about 14g of these antibodies to treat a patient, says Yuri Gleba, CEO of Icon Genetics, the German company that pioneered the platform, and to produce that much requires around 78 tobacco plants and about seven to 10 days.

A team led by Gleba is helping Mapp Biopharmaceuticals to optimize that production and to make the entire process more efficient so it requires fewer plants. “If everything is properly optimized, those plants can be full of that antibody,” he says. (Mapp officials declined to comment for this article on the status of their ZMapp production.)

MORE: Ebola Treatment May Emerge From Drug For Another Virus

Why plants? The time it takes to grow a plant is less time than it takes to genetically engineer a mouse or other rodent to produce human antibodies, which is how such products have been made in the past. It’s also less expensive. Plant-based manufacturing represents a promising new way of producing drugs that could cut the time it takes to bring critical medications, such as a flu vaccine during a pandemic, to a large number of people. Researchers have used the technology to develop a vaccine against norovirus, the infection that plagues cruise ships, for example, that is being tested now.

Here’s what that process looks like.

MORE: Potential Vaccine Shows Some Promise, but the Spread of Ebola Is Accelerating

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in Februar

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com