This article originally appeared on Patheos.

Every year during the time of hajj a feeling of nostalgia overcomes me as the media begins covering one of the world’s largest annual religious gatherings. Although I performed hajj almost nine years ago, the experience feels like yesterday. It was the journey of a lifetime.

But this year, hajj will take place against the ugly backdrop of a group that has come to represent the antithesis of what the pilgrimage signifies: Unity through diversity, brotherhood and equality, and the sanctity of religion, its symbols and holy places.

As ISIS sends another two hundred thousand Muslim Kurds fleeing into Turkey after terrorizing Christian, Yazidi, and other populations for months, millions of pilgrims in Islam’s two holiest cities are gathered to peacefully commemorate Abraham, the father, not only of Islam, but of Judaism and Christianity.

The entirety of the hajj takes place in and around Mecca and commemorates the life and struggles of Abraham, who is revered as an important prophet in Islam. Many of the themes and rituals of hajj focus on Abraham’s devotion and submission to God and the sacrifices that he and his family made. They include walking in the footsteps of Hagar, the mother of Ishmael, whom all Muslims emulate when they perform the required ritual known as Sa’i. During the ritual pilgrims run or walk swiftly in Hagar’s footsteps to commemorate her desperate search for water for her young son — water which eventually gushed up at his feet in what would become known as the well of Zamzam.

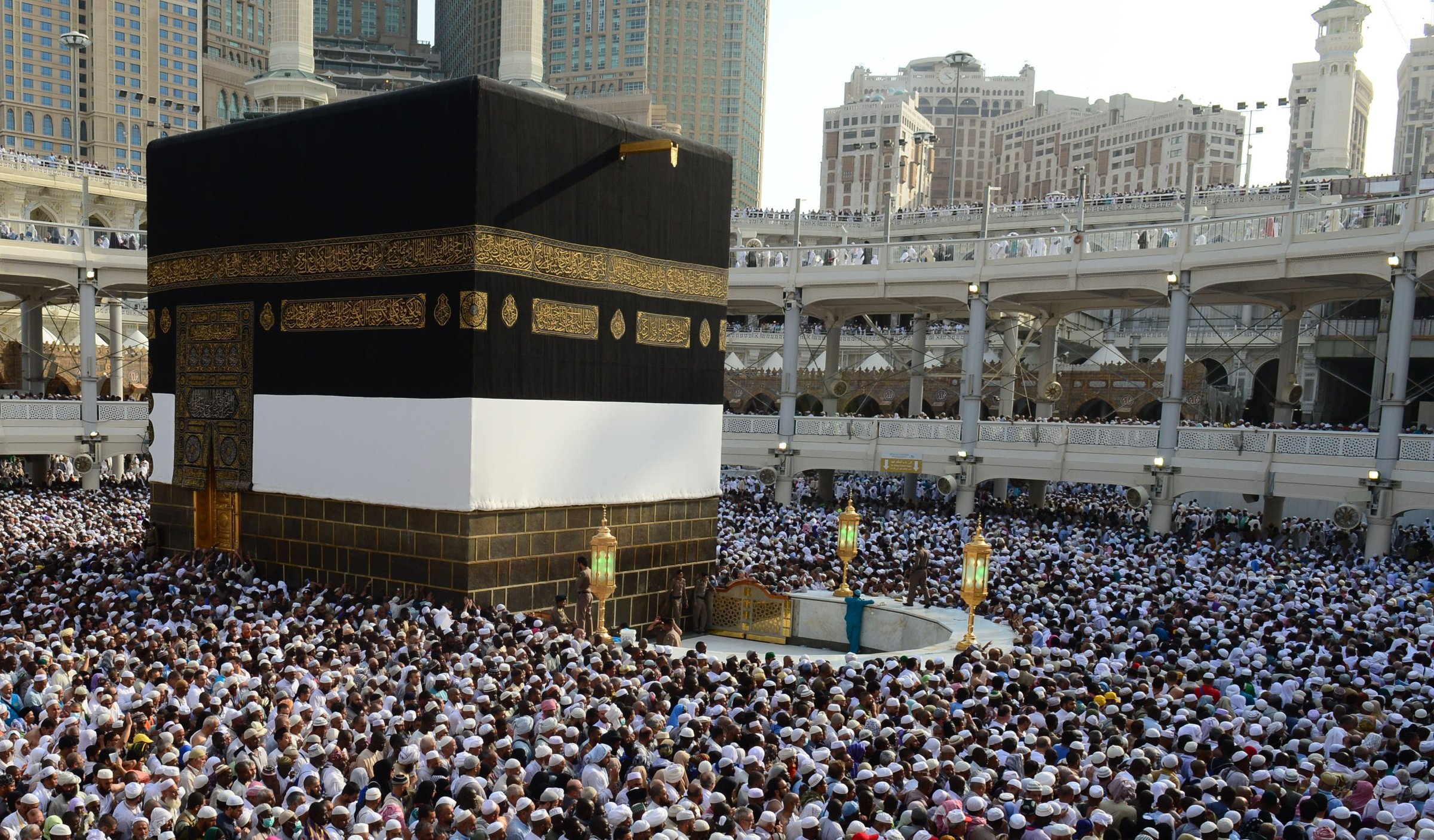

Another major theme of hajj is the interconnectedness of humankind, which is demonstrated by the simple white pieces of cloth which all male pilgrims wear during the duration of the hajj, no matter from where in the world they come.

One of the first things that struck me when I landed at the airport in Jeddah was the variety of airlines, each carrying pilgrims who had come for one singular purpose – to perform the fifth pillar of Islam which is required of all adult Muslims at least once in their lifetime if they are physically and financially able to make the journey. While I was unable to communicate in words with most of the pilgrims who hailed from every part of the world, there was little need for words. We all performed the same rituals, speaking an unspoken language of common purpose and objective.

Central for the diverse group of 2-3 million people gathered for communal worship, is the Kaaba, the cubical structure believed to have been built by Abraham and Ishmael as the first house of worship. One of the highlights of my trip, as it is for most pilgrims, was setting eyes on the Kaaba for the first time as it stood in its simple splendor in the center of a sea of humans circling around it.

At the end of the week 1.5 billion Muslims will celebrate Eid ul-Adha, the Festival of the Sacrifice, which commemorates Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son, a story also recounted in the Hebrew Bible. Muslims across the world mark the holiday by sacrificing a lamb and sharing its meat with those in need. This year, Muslim charities offer dozens of choices for people who want to sponsor a sheep in countries where poverty and war have made meat a rare and expensive luxury. This act of sharing with those in need is at the heart of two other major Islamic pillars, zakat, or poor-due, and fasting in Ramadan.

All of these acts of worship have the dual goals of bringing adherents closer to God and encouraging good character, including the good treatment of other people. Ihsan, or moral excellence, is said to be the highest level of Islam.

Especially at this holy time, the stark contrast between the lofty goals of the religion and the actions of groups like ISIS, Boko Haram and others who make a mockery of Islam with their brutal and merciless behavior is a painful reminder that religion is not about terminology or slogans. Rather, true religion is explained in a saying of the Prophet Muhammad, “I was only sent to perfect good character.”

Ameena Jandali is the Content Director for ING. Islamic Networks Group (ING) is a non-profit organization that counters prejudice and discrimination against American Muslims by teaching about their traditions and contributions in the context of America’s history and cultural diversity, while building relations between American Muslims and other groups.

Read more from Patheos:

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com