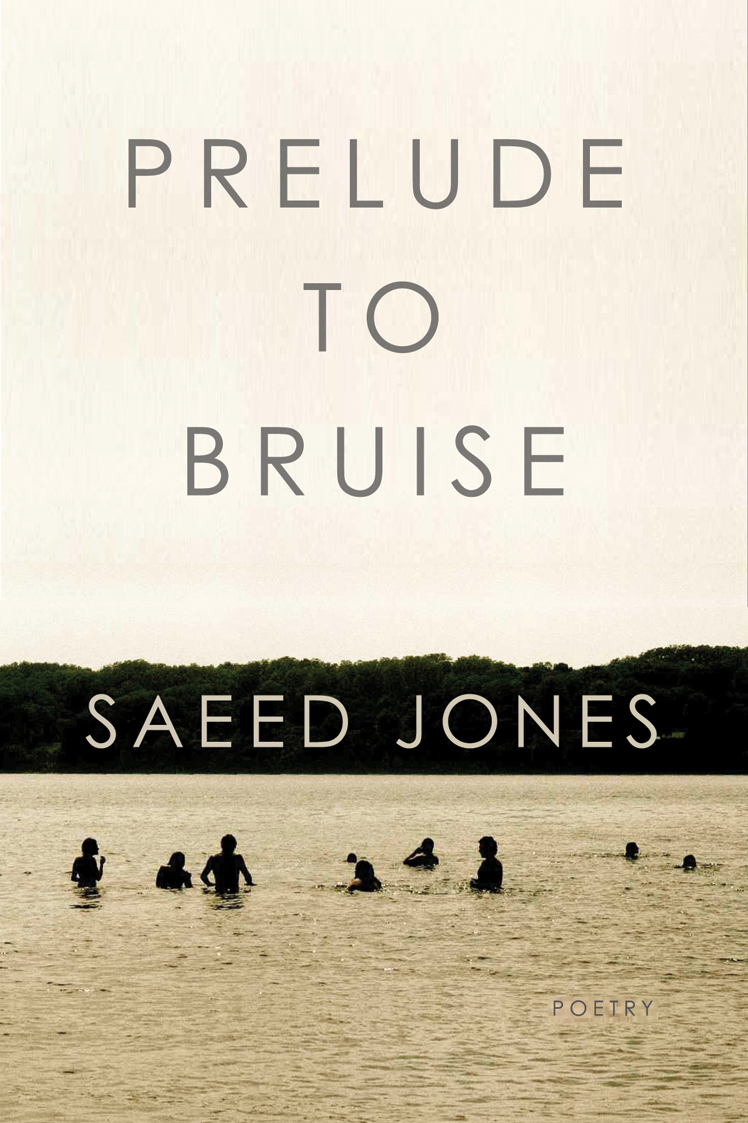

When he’s not editing BuzzFeed’s LGBT vertical by day, Saeed Jones is also a poet. His debut collection, Prelude to Bruise, hit shelves earlier this month, and though listing its topics hardly does the critically acclaimed book justice — you’ll have to see the words arranged on the page yourself — the way these poems address violence, life in the south, race, sexuality and relationships makes for an engrossing read best consumed in as few sittings as possible.

TIME met up with Jones last week to talk about his work.

TIME: You live in New York now, but many of these poems are several years old and were written in the South, where you’re from originally — as well as during other travels. Is this book closing the chapter on that time in your life, or going back in to investigate it?

Saeed Jones: Yeah, it is [closing a chapter]. There’s a line in the very last poem in the book where I say, “I’m in the woods again.” That’s often how I felt working on the book. I would think I was finished, and then another door would open, and I’d be like, crap! I’m still here! When am I going to be done with this? It feels very good to have the book finished and out there.

Anything you write is filtered through your life, so even though I may not say in the poems, “I too am on a journey as a writer!” I like that that comes through and really shaped the physical shape of the poems — they start to look different as you move. It’s important that the speakers have revelations and a sense of age. By the end, the speakers certainly sound older, the dynamics of the relationships feel differently.

Talking about the book does bring things back, and you find yourself realizing things about yourself and the poems I maybe wasn’t really thinking about at the time. I realized I was trying to answer some questions. One of the questions was, how are we using other people and their bodies to understand who we are? And that’s in terms of sex, that’s in terms of relationships, that’s in terms of sexual orientation. It’s experimenting, right? Certainly your first few relationships, you’re kind of figuring this out, and that requires having another person to work with. That’s actually kind of weird! For me, one way that I know I’m clearly in a different point in my life is that I’m not in any way interested in experimenting with identity in the way that I was when I was in my teens and early 20s.

Yeah, I was going to ask about the powerful body imagery you have here — that seems like such a focus of the book.

Aside from mythologizing coming of age, the book is also about black men’s bodies. I was thinking a lot about the way black men are written about and described, how we become hooded figures and this very particular assumption of masculinity. Where does that leave queer black guys? Who are often just as nervous and human as anyone else? I’m not trying to steal anyone’s purse! I’m maybe looking over my own shoulder. Everyone’s in peril in these poems — no one is safe. No one is going to save you in these poems. Being deeply aware of your mortality, that there are bones and blood and how easily we can bleed and be cut, that is something I’m always thinking about. Hopefully it’s a way to remind us of the value of life, even if it’s someone who’s very, very different from you. I hope you don’t have to be a black gay guy from the South to understand the journey these speakers are on in the course of the book.

Also, Americans love sex, obviously. But we’re still very Victorian about sex, and that’s something that’s always irritated me. So why not just start there? Start in the bedroom! And it’s fun to write about. I remember reading a poem once where someone was writing about spreading jam on toast, and I was like, “I couldn’t write that!”

A lot of these poems deal with trying to move on from your past while still acknowledging the ways your past has shaped you.

Over the course of the book, everyone’s remembering, and kind of under siege by, their past and not doing the best job of moving on. Certainly as an LGBT news editor, I see that when I’m reading stories: LGBT people who have survived but maybe have not had the opportunity — because it is a certain kind of privilege — to process. And if you don’t process, I do think there’s a reliving, recreating circumstances.

Roxane Gay actually said this yesterday [at a BuzzFeed event]: it’s always helpful when you’re thinking about whatever your history is, whatever is true, one fact is certain — you’re not still there. I think that’s very helpful. As I was working through the book and reflecting, I started thinking about, well, okay, this character is struggling, I’m struggling, but we’re also alongside other people who are struggling. You in the present moment are surrounded by people who are also on a journey. That’s the question in the poem “Body & Kentucky Bourbon.” He’s been in this relationship with this man, and it’s ended, and only after it’s ended is he able to think about, wait, this guy had a past too that he was grappling with. I’m sure he would have liked to have been able to figure that out before.

As someone who’s very new to poetry, I’m still getting used to the ambiguity of it — what’s happening, who is speaking, is this real life? Is that as liberating for you as it is unsettling to a first-timer?

It’s amusing! I can see it sometimes when I’m talking to people. I can often see the flash of trying to understand. I do think it’s part of American book culture. We’re used to fiction and nonfiction, and we’re obsessing over a memoirist fictionalizing and a novelist drawing from biography. Poetry is, “We don’t know what to do with it!”

Often when people see an “I” in poetry, there’s an inclination to assume its autobiographical. Once I remember someone asking me what it’s like to be writing and dealing with being a survivor of child abuse, and I was like, “Oh! I am not a survivor of child abuse.” There are certainly shards of my life in the book. But it’s usually details. It’s usually setting. Like, I did have sex with a boyfriend in the woods, but it was at a party! We weren’t running away from home. My house obviously isn’t on fire. I’m sure there are some readers out there who are very worried about me.

Is there more of a risk in the poetry world of becoming “a black queer poet” versus a poet who happens to be black and queer and write about those things?

I’ve been to readings where I’ve been packaged as a Southern writer, and at other readings, it’s black writer, queer writer. It’s always being arranged. Typically it’s for the audience — it has nothing to do with me. I think about the 18-year-old gay kid that I once was in Texas. If I found out there was a reading and there was a gay poet and saw that in a bio, I would go! As long as my work is out there and able to get into peoples’ hands, and as long as the questions are thoughtful and in good faith, I’m fine.

Not that writing a book of poetry and writing for the Internet strike me as particularly at odds with each other, but has working for the social web changed anything about how you work and write?

It’s a good question, and it’s something I think about. I’ve been working on a memoir since I started at BuzzFeed, so I haven’t been writing a lot of poems. But it has to have an impact on my writing process. Because I’m online all day and am reading all day, it reminds me that readers, wonderfully, have so many options. Maybe that’s why it is an intense book and all the poems have their fingers curled. I don’t feel like wasting someone’s time with poems about the weather. There’s a sense of urgency that I’ve gotten from engaging in the social web. Looking at your TweetDeck, there’s so many things shouting urgency at you. What does that mean for literary writers? We have to be very honest with ourselves. Why am I writing this? Am I writing this because I want to write a poem? am I writing this because I want to publish a book? Only you know the answer to that question.

Do you hear from a lot of first-time poetry readers who try out the book because they know your other work?

Yeah. I think for any poet, certainly in America, that is a constant, and it is a wonderful compliment. Often the way we’re taught poetry when we’re educated here is we’re reading great poetry written centuries ago, if not decades ago. Shakespearean sonnets become all of poetry, though there is wonderful poetry being written all the time that’s narrative or whatever would make people feel more comfortable. This book, it does push you to read it in one sitting, because you’re like, what’s going to happen to this seemingly disaster-prone young man? His father is hunting him with a rifle! I want to turn the page and see what happened.

Binge-watching poetry! Though I guess that’s basically just reading a book.

Totally! That’s how I stumbled into what the book became. I was writing a lot of poems in the southern landscape, and it was three years before the Boy [a character in many of the poems] even appeared. I got curious about him. It started with the poems about the mother’s dresses, and I was like, why would he be so interested in his mother’s dresses? That process reads like a bit of a novel.

Does poetry have a capacity to go viral? You mentioned something just now about discovering all the poetry out there that could be up your alley, and I remember having that realization when I first came across Patricia Lockwood’s work. Her “Rape Joke” poem obviously hit a nerve on the Internet.

Patricia Lockwood certainly figured it out very successfully. I’m pretty stubborn with poetry. I like writing in so many different forms — if it’s an essay, I’m going to write an essay! I don’t know if one of my poems would ever be able to go viral, honestly. But there’s huge potential. If people can memorize entire sections of The Iliad, why not?

Part of the reason Patricia Lockwood’s poem worked so well was because it was so in line with the engine of the conversation we’re already having. It works as a beautifully written and structured poem as well as an essay. Prose poems in particular, that are straddling that, I think, are totally possible. Poetry emphasizes language, and obviously on the social web, outrage-driven stories, whether it’s something the police chief in Ferguson said, or Alessandra Stanley’s “Angry Black Woman” [article about Shonda Rhimes in the New York Times], so often the things that are driving these conversations online are about language. Poetry distills the focus and forces you to look at blue-black, boy, burning. You’re looking at words that can illuminate the way we look at everything else, because in general we have a more casual relationship with words.

So I would love to see more poems go viral. But in order for that to happen, it has to be in step with that conversation — and genuine! Oh my gosh, if people still writing poems with the intention of going viral? God help us.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Nolan Feeney at nolan.feeney@time.com