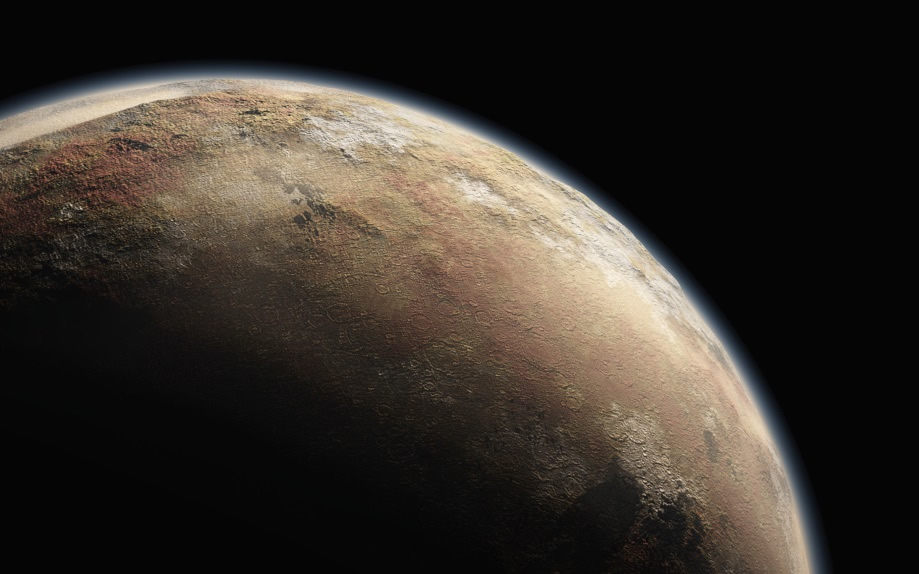

When Pluto was hurled from the pantheon of planets back in 2006, it could simply have slinked away, accepting its new title of “dwarf planet” without a fuss. But thanks to the undying support of its millions of fans—not just schoolchildren, but many astronomers as well—the little planet that could is still a contender.

The latest evidence: a debate at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, in which three astronomers squared off to present both sides of the question: “Is Pluto a Planet?” And when the dust settled, the audience, made up mostly of ordinary citizens, declared once again that the answer is “duh, obviously.”

Three may seem like one side too many, but David Aguilar, the Center’s director of public affairs, who set up the debate, wanted to look at the question not just from a scientific perspective, but also through the lens of history. The first speaker, therefore, was the eminent Harvard astronomer and historian of science Owen Gingerich. “Planet,” he pointed out, “is a culturally defined word that has changed its meaning over the ages.”

In fact, the word itself comes from an ancient Greek word meaning “wanderer.” Unlike the stars, which seem fixed in place, the planets are objects that wander from one constellation to another in the sky—and since the Sun and the Moon do that too, they were originally considered planets as well.

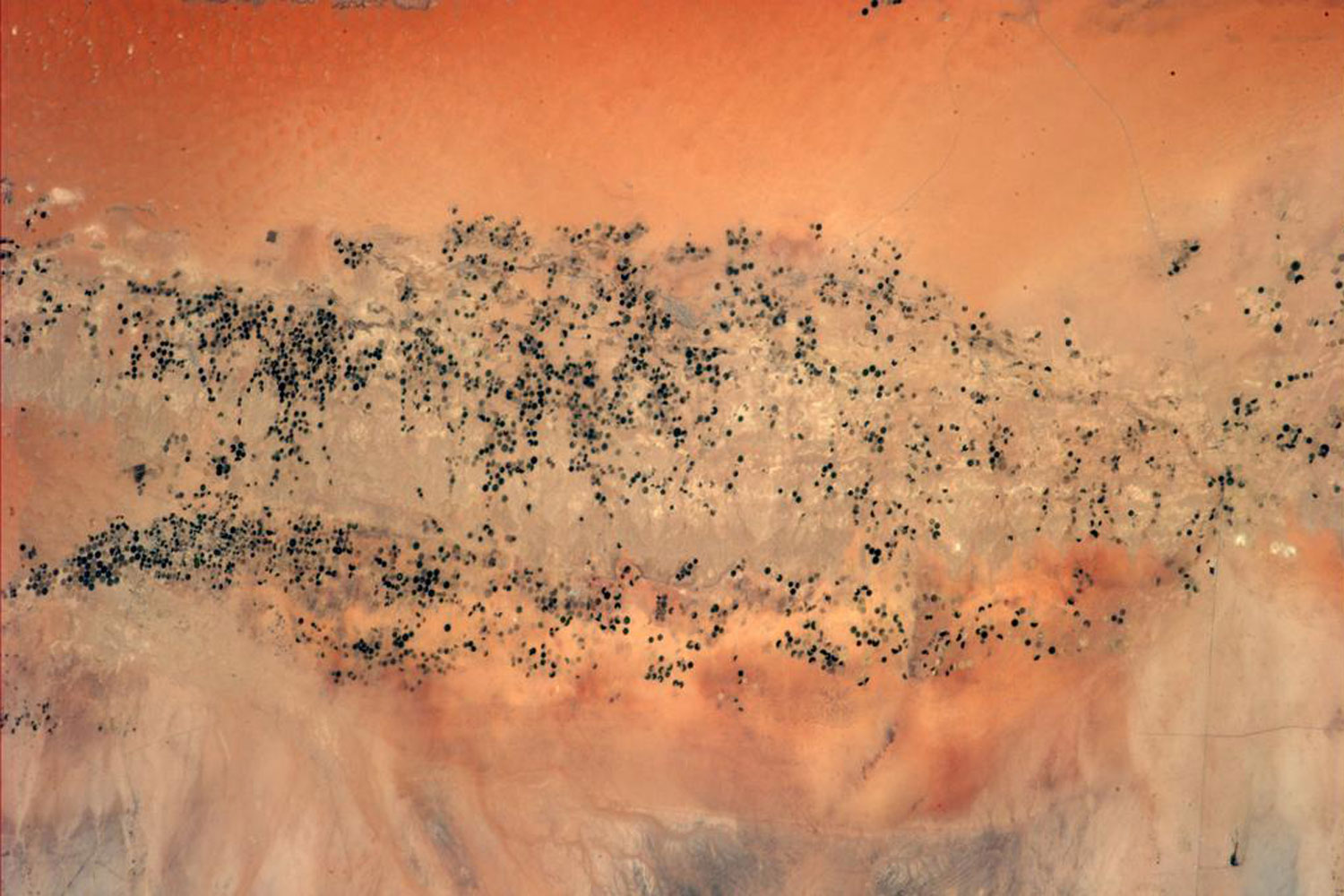

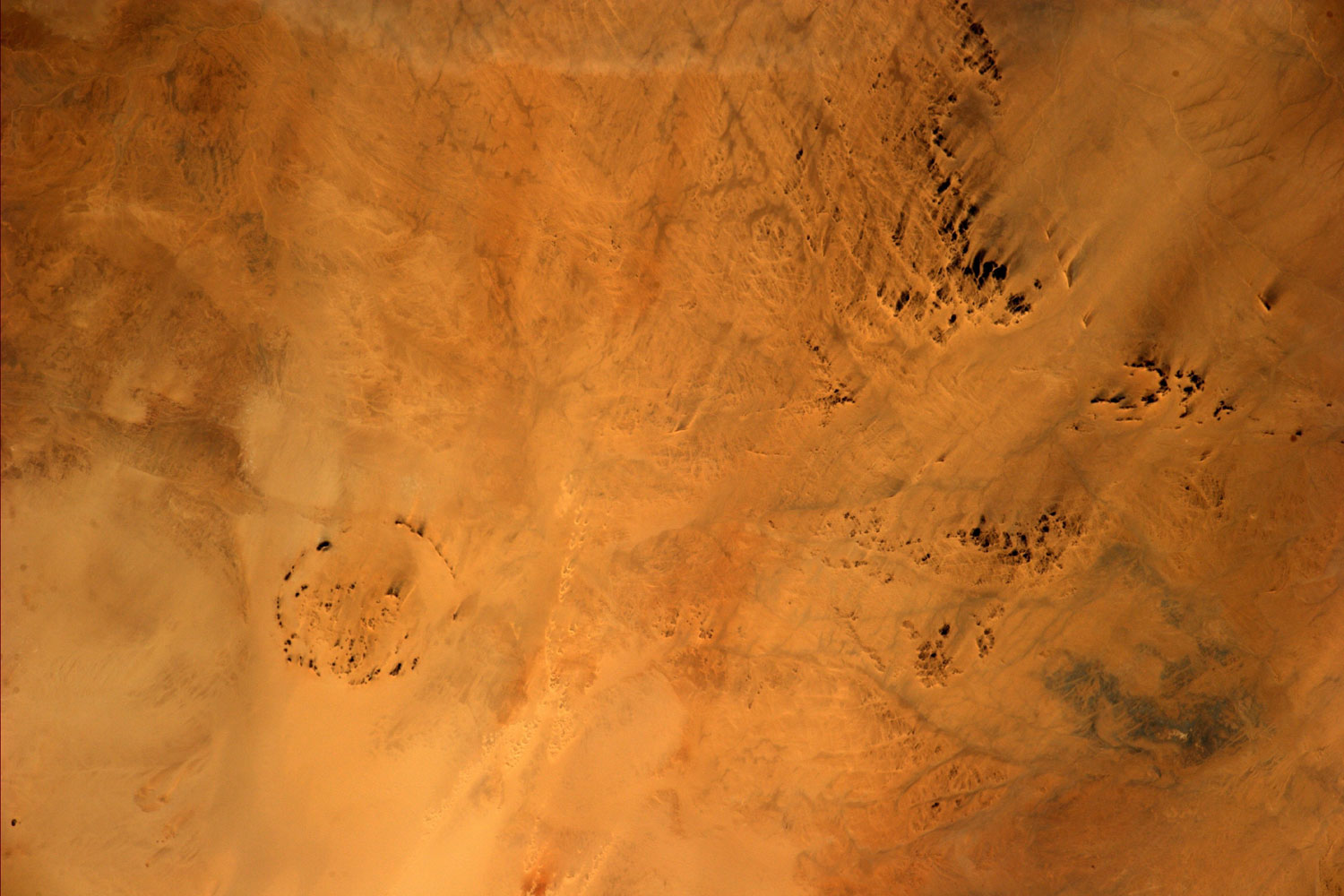

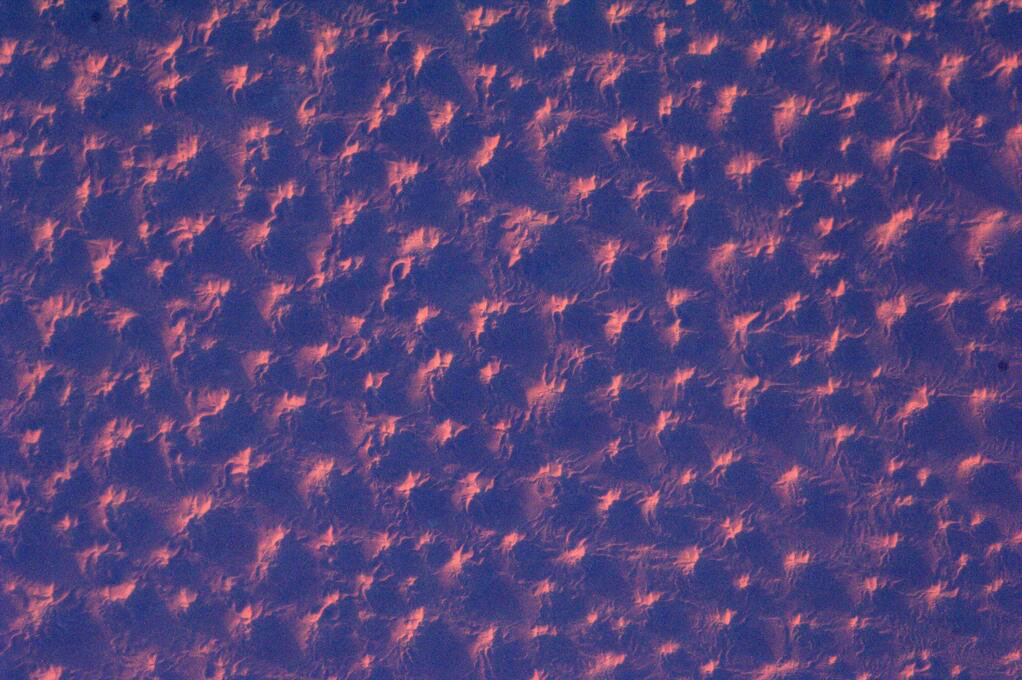

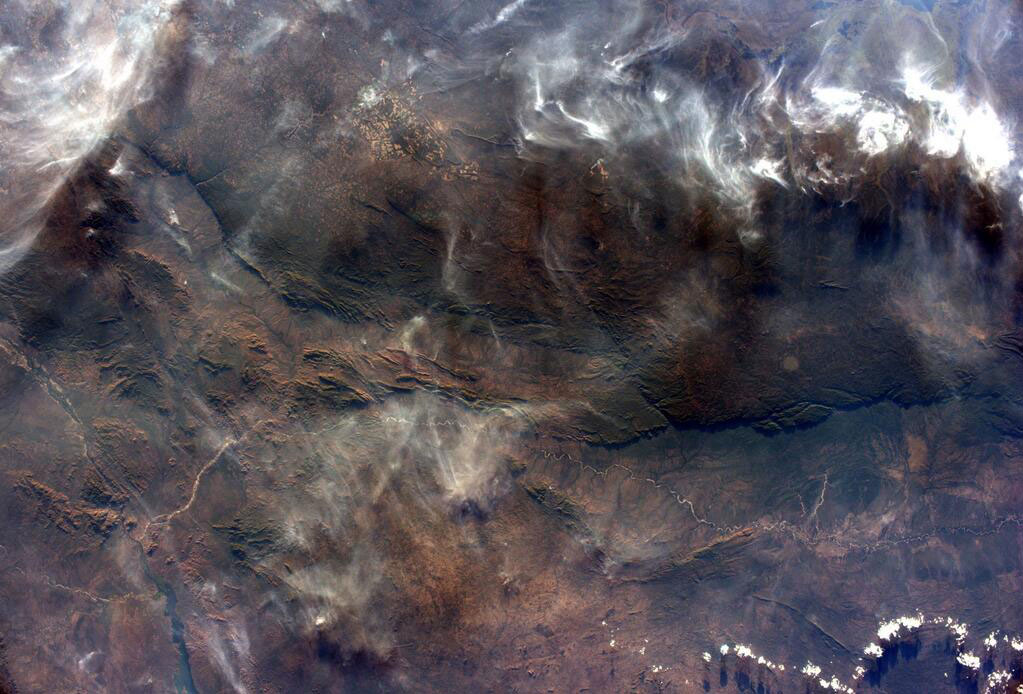

PHOTOS: This Astronaut's Images of Earth Look Like Beautiful Abstract Paintings

That designation didn’t last, of course, but when astronomers began finding asteroids in the early 1800’s, they were also counted as planets, at least as first, (The fact that astronomer William Herschel had recently discovered the new planet Uranus had evidently given the scientists’ a taste for more.) Within a few decades, though, astronomers found so many asteroids that things were getting confusing. Objects like Ceres and Vesta, the largest asteroids in the asteroid belt, were demoted from “planet” to “minor planet,” in a foreshadowing of Pluto’s fate a century and a half later—and it had nothing to do with any sort of scientific definition of the word.

And neither did the International Astronomical Union’s decision to downgrade Pluto in 2006. Just as with the asteroids, astronomers began finding additional Pluto-like objects starting in the 1990s, including Eris, which turns out to be essentially the same size as Pluto. If Pluto is a planet, so is Eris, and so are several other objects at the edge of the Solar System.

That would be just too confusing, argued the second debater, astronomer Gareth Williams, associate director of the IAU’s Minor Planet Center. If you let Pluto stay, he said, you logically have to let the number of planets rise to 24 or 25, “with the possibility of 50 or 100 within the next decade” as more objects are found. “Do we want schoolchildren to have to remember so many? No, we want to keep the numbers low.”

This isn’t exactly a rigorous scientific argument—so to give its decision the flavor of science, the IAU came up with a definition of “planet” so convoluted it seemed entirely arbitrary. To qualify as a planet, a body must orbit the sun and be large enough to be at least roughly spherical—two rules that make sense. But it must also have gravitationally “cleared its neighborhood” of other bodies, meaning it has its orbital traffic lane all to itself, which Pluto doesn’t—at least during the most remote portion of its journey around the sun. The rule seemed carefully crafted so that “dwarf planets” like Pluto, Eres and the asteroid Ceres didn’t make the cut.

“It didn’t make sense at all,” said Center for Astrophysics communications director David Aguilar, who set up the debate. “Isn’t a dwarf fruit tree also a fruit tree? Isn’t a dwarf rabbit a rabbit?” But in the end, the resolution was approved by IAU members, and in 2006 the number of planets was pared from 9 to 8—the ones known to science pre-Pluto.

The last debater was astronomer Dimitar Sasselov, director of Harvard’s Planets and Life initiative. His argument, he explained in a conversation after the debate, was that the word “planet” does need a scientific definition, but that we don’t know enough yet to create one. The reason: we’ve discovered thousands of planets orbiting stars beyond the Sun, and until we can understand how they formed and what they’re really like, any definition is premature. Pluto may be a planet based on scientific reasoning, or it may not be. “For now,” he said, “we should keep Pluto as a planet by default.”

In the end, the Harvard audience voted in favor of Pluto’s reinstatement by a landslide. Planetary scientist Alan Stern, whose new New Horizons probe will reach Pluto next summer for a first-ever close encounter, wasn’t there. But when he heard about the vote, he said, “every time there’s a poll it turns out this way. The IAU have become largely irrelevant in this.”

The organization may seem to count even less when you consider something Gingerich revealed during his arguments. He was there for the 2006 IAU vote, which came when most of the attendees had already gone home. Just 424 of the organization’s nearly 10,000 members were present, and when the organizers offered the gathering the chance to reconsider Pluto’s demotion, Gingerich said, “they voted not to vote again because they wanted to go to lunch, so that was the end of it.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com