With the midterm elections approaching, U.S. politics is unusually dopey and depressing.

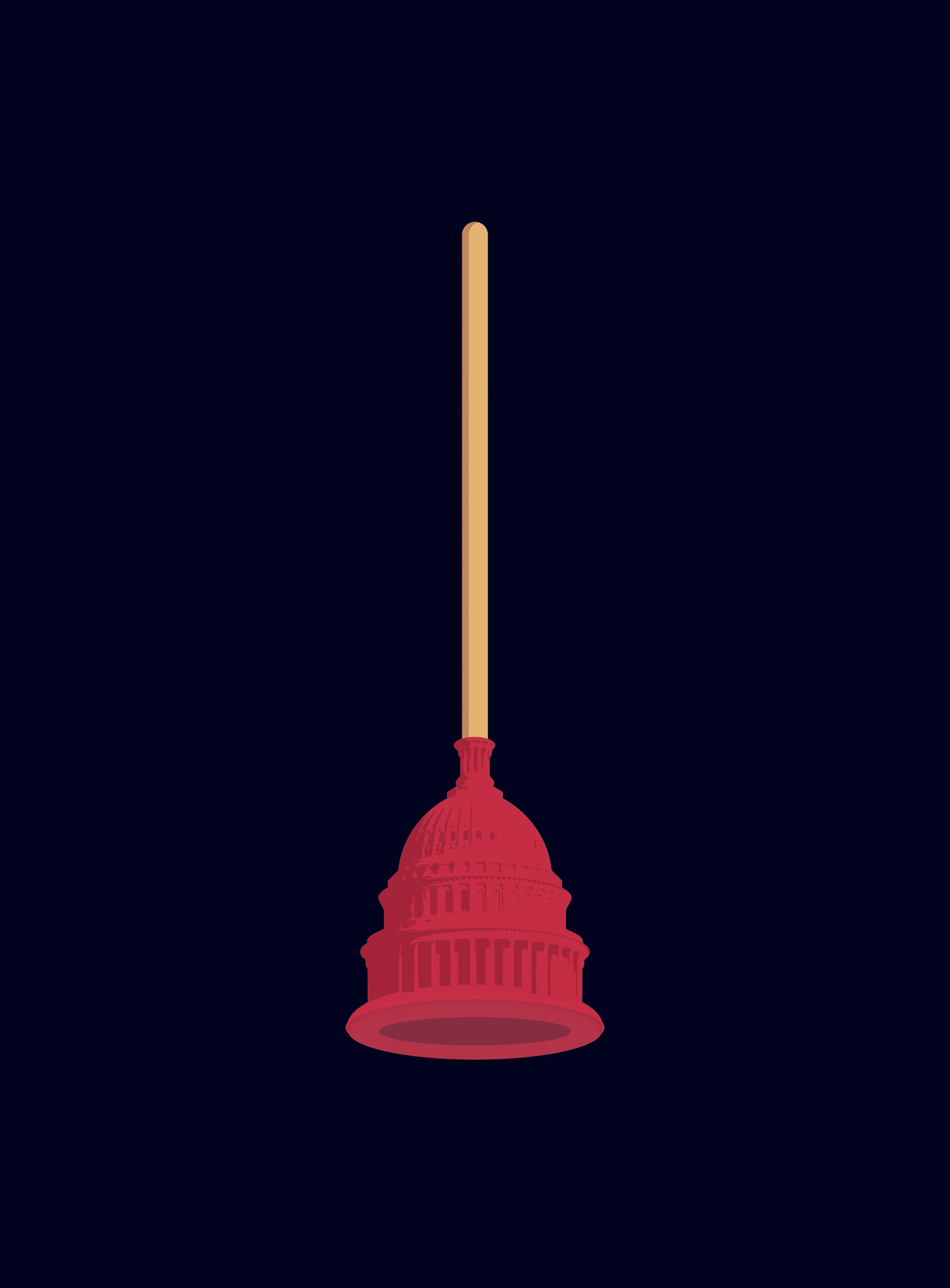

The previous Congress was the least productive in history. The current Congress has done even less. Efforts to reform gun laws, immigration policy and the tax code stalled. The main substantive debate has involved the arcane Export-Import Bank–not a debate on which the fate of the Republic depends, though quite consequential compared with cable-TV slugfests over President Obama’s golf habits. Legislators have stopped pretending that they might break the gridlock; Congress has been in session for only eight days since the end of July, and it isn’t going back to work until mid-November.

With no hope of governing, both parties are focusing on messaging. Off-year elections are won by turning out the base, so Republicans are trying to energize conservatives by obsessing about Benghazi and suing Obama, while Democrats are trying to energize liberals by warning that impeachment is next. Democrats have highlighted unpopular Republican views on issues like women’s health, gay rights and the minimum wage, while Republicans have tried to force vulnerable Democrats into tough votes on issues like the Keystone pipeline. House Speaker John Boehner, upset that his messaging efforts didn’t get more attention, recently issued a press release titled “8 Shark GIFs That Perfectly Explain Why Senate Dems Can’t Ignore House Republican Jobs Bills,” perfectly capturing the ugh of politics in 2014.

Polls suggest that the public is disgusted with Obama, disgusted with the GOP and completely nauseated by Congress. Talking heads in both parties are talking up the high stakes in November, with Republicans hoping to take control of the Senate just as they seized the House in the 2010 midterms. In reality, the stakes in this election are pretty low. If Republicans flip control of the Senate by ousting Democrats who won in red states in 2008, Democrats will probably flip it back in two years by ousting Republicans who won in blue states in 2010. In any case, the stalemate in Washington is virtually certain to continue after November whether the Republicans flip the Senate or not, because Obama will still be President and Republicans will still control the House.

Even the President admitted that he expects gridlock to continue no matter who wins the Senate. The best rationale he could provide for the importance of the midterms was that without a Democratic Senate, he’ll have trouble communicating the Democratic message. “Having a Democratic Senate that can present those issues and put them forward, even if House Republicans fail to act, means we’re debating the right stuff for the country.” Not exactly a rallying cry.

Inertia does not produce uplifting politics. It produces obsessions over a traffic jam in Governor Chris Christie’s New Jersey, over obscure campaign-finance violations in Governor Scott Walker’s Wisconsin, over Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell’s ad featuring stock footage of basketball players from Duke instead of Kentucky. I just checked the latest campaign uproars in my Twitter feed: The Democratic candidate for Senate in Iowa is under fire because he once squabbled with a neighbor whose chickens wandered into his yard. The Republican candidate for governor in Illinois apparently paid $100,000 to join a wine club. Someone said Walker has given women “the back of his hand,” which Republicans found so outrageous that his Democratic challenger, who didn’t say it, was being pressured to apologize for it.

But there’s a more pleasant way to think about the politics of nothing, a happier explanation for the dreary stalemate. One reason the two parties fight so bitterly over petty stuff is that they’ve already achieved their major goals. They’re fighting over relative scraps. Our politics is about “first-world problems,” the silly battles a strong nation with an improving economy and a dominant military can afford to have.

These days, Republicans don’t have much of an agenda beyond opposing whatever Obama is for, but that’s partly because they’ve had so much success on issues like taxes, welfare and crime since the Reagan revolution. Democrats don’t have much of an agenda either, but that’s partly because Obama has enacted so much of his. He engineered a massive stimulus bill, record investments in clean energy, ambitious school reforms and sweeping Wall Street reforms. And his Affordable Care Act became the law of the land, a major step toward the long-standing Democratic dream of universal health insurance.

Obamacare in particular represents the culmination of an ancient battle in U.S. politics, the war over the welfare state that has raged since the New Deal. It has been the most divisive issue in national politics for the past 80 years, animating the fundamental philosophical split between the two parties. The long war may be winding down. The future of our politics will depend on what replaces it.

“The Final Strand in the Safety Net”

Franklin D. Roosevelt wanted to include “compulsory health insurance” in the Social Security Act of 1935, but his advisers said opposition from the Republican Party and the medical lobby would endanger the entire bill. So the government response to the Great Depression created unemployment benefits and old-age benefits but not health benefits. “Health care was the orphan of the New Deal,” says Jacob Hacker, a domestic-policy expert at Yale University.

Gradually, the safety net expanded. Social Security benefits got much more generous. Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society extended health care to the elderly and the needy through Medicare and Medicaid, along with food stamps, Head Start and other War on Poverty programs. But when Obama took office, there were still nearly 50 million Americans without health insurance plus tens of millions more with unreliable insurance. As Hacker put it, Obamacare aimed to provide a home for the New Deal’s orphan, covering the uninsured while prohibiting insurers from using pretexts like pre-existing conditions and lifetime limits to deny treatment. “It’s the last fundamental piece of the social-insurance vision,” Hacker says.

But politically, Obamacare was an immediate disaster. The 2010 midterms were a brutal vote of no confidence.

That December, the centrist Democratic group Third Way suggested in a memo to Obama that he should respond by using his 2011 State of the Union address to turn the page on 80 years of Democratic rhetoric, to “declare the passage of health care as the final strand in the safety net.” America was committed to protecting its old, its poor and now its sick–“a tremendous legacy to honor, but there is no major new thread to weave,” the memo said. It was time, Third Way argued, to announce that the welfare state had reached its logical conclusion–and that Obama was moving on to new priorities.

“Such a pronouncement by the President will be seen as a bold and profound shift for the Democratic Party, far more so than President Clinton’s pronouncement that ‘the era of Big Government is over,'” the Dec. 14, 2010, memo concluded.

After a vigorous West Wing debate, the President’s aides rejected the advice. They thought it would sound like a cheesy throwback to Clinton’s line–and get shredded instantly on social media. They also thought it would sound like a surrender to the Tea Party, infuriating the liberal base the President needed to get re-elected. “We can’t just say: ‘O.K., you win,'” argued Obama’s top political adviser, David Axelrod.

Instead, Obama’s State of the Union theme was “Winning the Future.” His defiant mantra was: “We do big things.” He defended government against Republican attacks, calling for new investments in education, infrastructure and research. And that anti-antigovernment framing helped him win a second term.

He hasn’t done many more big things, though. The parties have spent much of the past several years relitigating Obamacare, with House Republicans holding dozens of votes on repeal and most Republican governors opting out of its provisions extending Medicaid to uninsured families. After the botched launch of the program’s website, many Republicans vowed to make 2014 a referendum on Obamacare.

But signups ended up exceeding the Administration’s goals. GOP-forecasted “death spirals,” soaring premiums and other Obamacare failures have failed to materialize. And energy has drained out of the repeal movement. Obamacare still polls badly, but repeal polls worse, and many voters support the law’s provisions even though they oppose the law.

In other words, the politics of fear has given way to the politics of loss aversion. Americans simply don’t like having their benefits taken away. It’s telling that the GOP is running ads attacking Democratic Senators Mark Pryor of Arkansas and Kay Hagan of North Carolina for supposedly considering Social Security cuts, just as Mitt Romney attacked Obama in 2012 for cutting Medicare. Politicians talk about entitlement reform, but they know voters like their entitlements. In fact, Pryor and Alaska Senator Mark Begich have attacked opponents for threatening Obamacare’s benefits, although their ads never mention “Obamacare.” Democratic challengers are also going after Republican governors like Walker in Wisconsin and Rick Scott in Florida for turning down federal money to expand Medicaid. Obamacare has already extended health benefits to more than 10 million uninsured Americans, and that number will gradually increase. Third Way was right: Obamacare is filling in the main gap in the Democratic vision of a safety net that protects all Americans.

“The President won that argument,” says Michael Strain, a scholar at the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute. “Republicans can’t just say, Hey, let’s go back to where we were in 2008. You can’t run on taking away people’s health care.”

Republicans have won some arguments too. As Strain points out, the top income tax rate was 70% before Reagan took office; in recent years it’s bounced between 35% and 39.6%. Tax increases on the nonrich have become nonstarters at the federal, state and local levels, a testament to the success of the GOP antitax message. Meanwhile, America has gotten tougher on crime and attached work requirements to welfare. Republicans have also largely gotten their way on robust military spending, turning “soft on defense” into a political kiss of death. And discretionary spending–the ever shrinking sliver of the federal budget that isn’t reserved for defense or the safety net–is at its lowest level since Eisenhower was President. Those are big GOP victories. In surveys, Americans often seem to embrace Republican rhetoric, expressing aversion to Big Government and Big Spending even though they express support for the goodies that Big Government provides. There are even elements of the Obama agenda that borrow heavily from Republican ideas, particularly his education reforms, despised by Democratic-leaning teacher unions, as well as his health reforms, inspired by Romney’s efforts in Massachusetts.

But whether or not you like the Obama agenda, he’s made most of it happen. He’s launched a budding clean-energy revolution. He’s cut taxes on the poor and middle class while raising taxes on the rich. He’s kept his promises to cut health care costs, slice the deficit in half and let gays serve openly in the military. And while Republicans opposed most of those initiatives, they’re not really clamoring to roll them back, at least not when they’re trying to reach voters beyond their base. For example, Cory Gardner, a conservative Republican Congressman in Colorado, is talking up his support for wind energy and over-the-counter contraception now that he’s running for the Senate.

This is the irony of our divisive politics: many of our most divisive arguments are fading. Republicans in close races rarely pontificate about gays. Few Democrats run against guns. Republicans have blocked efforts to legislate equal pay for women, but it’s a sign of the times that they’re now trying to airbrush that history; the Republican National Committee recently tweeted that “All Republicans Support Equal Pay.” A lot of Washington fights are fake fights.

Still, it’s worth asking: If we had a politics of something, what would it be about?

Agendas for the Future

The conventional beltway wisdom is that Obama has checked out, but his team says he’s just more realistic about Republican obstruction. There are no longer frequent West Wing meetings to discuss a fiscal grand bargain or other big bipartisan deals. Now the focus is on implementing Obamacare and other legacy initiatives while devising smaller initiatives that can bypass Congress, like his My Brother’s Keeper mentoring program for minority youth and an effort to streamline permits for public-works projects. The combination of Capitol Hill gridlock and growing global turmoil has diminished Obama’s focus on domestic policy, but his aides insist he’s still driving hard–and not just on the fairways.

“If you’re tired,” he recently told staffers, “then leave.”

The larger question for Democrats is what happens to their agenda after Obama. Much will depend on their presidential nominee–front runner Hillary Clinton has avoided specifics–but two themes emerge: economic inequality and economic competitiveness. The gap between rich and poor has continued to grow under Obama, even though he boosted transfer payments like the earned-income tax credit, raised taxes on high earners and passed Obamacare. Some liberals would like to see a bolder push to require paid family leave and sick leave for workers, as well as stronger government backing for long-term care. French economist Thomas Piketty’s best seller Capital in the 21st Century has also renewed the left’s interest in wealth taxes, especially on estates.

But some Democrats are eager to shift their party’s focus from helping Americans in need to helping Americans compete. They will keep pushing some version of Obama’s “Winning the Future” agenda, which is currently stalled in Congress, with investments in high-speed rail, broadband and other infrastructure needs, as well as medical research, clean energy and 21st century schools. But you don’t hear Democrats talking about a new Marshall Plan for climate or infrastructure or cities or schools; New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s crusade for universal pre-K is as ambitious as they’ve gotten so far.

There are more ideas flying around on the Republican side, where potential 2016 candidates seem to recognize that their party can’t just appeal to the haves. Senator Marco Rubio has floated wage subsidies for struggling families; he also bucked his party last year by pursuing immigration reform, although he’s sounded less enthusiastic about it as its legislative prospects have dimmed. Senator Rand Paul has challenged lock-’em-up GOP orthodoxy on crime issues while questioning the militarization of local police forces and the intelligence gathering of the National Security Agency. Congressman Paul Ryan’s new antipoverty plan actually endorsed Obama’s call to expand tax credits for the working poor. “A year ago, it was just people like me saying stuff like that–and Ryan’s people were attacking me,” says Strain of the American Enterprise Institute, a leader of an intellectual coterie of “reform conservatives” who have pushed the GOP to broaden its message. “Now you’re seeing Tea Party guys recognize that we can’t just be about shrinking government and cutting taxes. It’s not 1979 anymore.”

It’s a fool’s errand to try to predict what politics will be about tomorrow. A Supreme Court vacancy could scramble 2014 or 2016. So could war with ISIS in Iraq or a new crisis involving Russia or Syria or Israel or Iran. The stock market could crash. The economy could tank. And there are fissures within both parties over issues like free trade, school reform, corporate subsidies and drones that could deepen in unexpected ways.

For now, our politicians keep reciting their old lines about Big Government and the safety net, about “we’re in this together” vs. “you’re on your own.” But they’re no longer even on the same stage. The question is when the audience is going to realize that–and when they’re going to shift to a new script.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com