This should be a time of excitement and anticipation for Britain’s opposition Labour Party. Delegates and politicians have gathered in Manchester for the party’s annual convention, its last big get-together ahead of the U.K. general election scheduled for May 2015. Since Ed Miliband became Labour leader four years ago — to the surprise of large swaths of Britain and his brother David, the former Foreign Secretary and bookmakers’ favorite for the role — his party has mostly maintained a lead over the David Cameron’s Conservatives. Britain’s Conserverative-Liberal Democrat coalition took office in 2010 and has introduced unpopular budget cuts, presiding over an affluent nation that has seen increasing numbers of cash-strapped citizens forced to use food banks. Labour should be looking forward to an easy victory next spring, and you’d expect the mood at its party convention in a city in northwest England that boomed during the industrial revolution and cradled Britain’s labor movement, to reflect that outlook.

Instead delegates to the Labour Party Conference, which opened on Sept. 21 and concludes with a guest speech from New York Mayor Bill de Blasio tomorrow, seem muted and apprehensive. The conference is sparsely attended. In days gone by, business tycoons and celebrities scenting a party about to gain power reliably swelled the numbers at such gatherings. This, by contrast, is a low key event. So why the long faces?

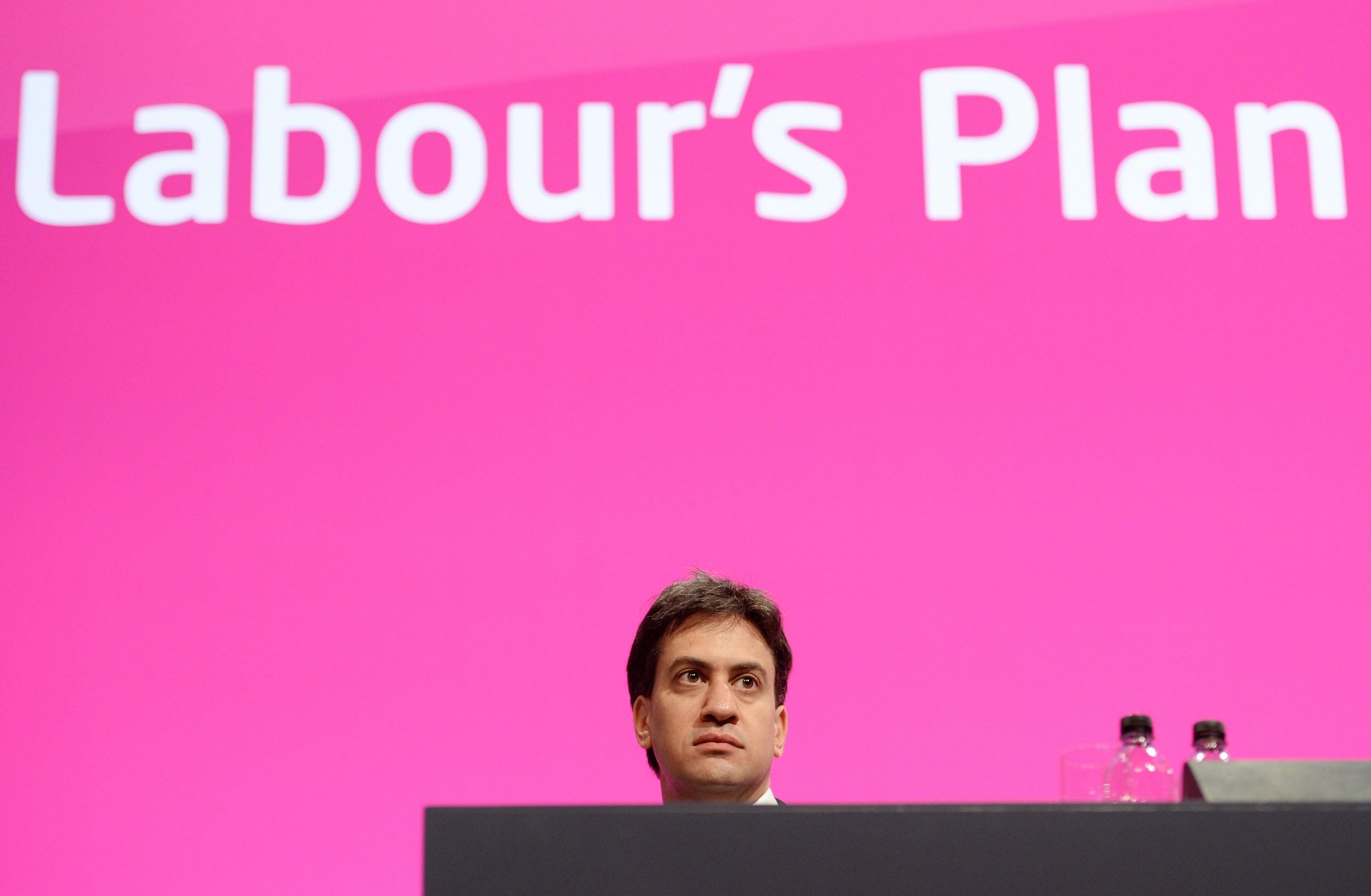

There are several reasons: Ed Miliband, a boyish 44-year-old, handsome enough but easily caught by photographers in cartoon-like expressions of befuddlement, has yet to convince Labour supporters or the wider public that he’s Prime Ministerial material. Pollster Ipsos-MORI recently revealed that only 30% of Britons consider him a capable leader compared to 46% who find him out of touch with ordinary people. His keynote address to the conference today marks a chance to change — or confirm — such views.

It doesn’t help that Labour’s poll lead over the Conservatives is modest: only 5 points according to the latest YouGov survey. Ahead of his stunning first election win in 1997, Tony Blair consistently polled leads in the double digits. Delegates glumly staring into their pints of beer in the bars of the Manchester Central Convention Complex see a murky prospect at the bottom of the glass: a possible coalition with the Liberal Democrats, tarnished in Labour minds by their current service in coalition with the hated Conservatives.

Yet the Lib Dems’ own electoral runes look so gloomy — they polled only 7% in the same YouGov survey — that this scenario too must be in question. All the mainstream parties have lost ground among English voters to the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), red in tooth and claw on issues such as the European Union (UKIP advocates Britain’s E.U. withdrawal) and immigration (UKIP doesn’t like it one bit). YouGov shows UKIP doing far better than the Lib Dems, with the right-leaning party polling at 16%.

And another populist party has left Labour with a yet bigger headache. The Scottish National Party (SNP) may not have steered Scotland to independence in the Sept. 18 referendum, but it succeeded in convincing 45% of Scottish voters to disregard the Better Together campaign and opt for a split. Better Together was, in theory, a cross-party initiative combining Conservatives and Lib Dems as well as Labour in collegiate efforts to keep Scotland in the U.K. In practice, the campaign was run by the Labour Party, the only one of the three mainstream parties to have a large support base in Scotland — and 41 members of Parliament with Scottish seats.

The lackluster Better Together campaign has raised questions about whether Labour has lost its connection to the Scottish electorate and whether it will, as a result, lose those seats. Speaking at a conference fringe meeting in Manchester last night, Douglas Alexander, Labour’s Shadow Foreign Secretary and head of Labour’s general election strategy, gave his perspective as a key member of the Better Together team and as a Scot. He said the SNP and UKIP were both benefiting from the same tailwinds — the British electorate’s lack of faith in mainstream parties to deliver. He also saw parallels with the rise of the Tea Party. “Westminster is assuming the same level of toxicity in the minds of British voters as Washington has in the minds of U.S. voters,” he said.

Britons’ trust in the mainstream parties has not been boosted by an unseemly scramble in the aftermath of the Scottish referendum vote to reinterpret promises made to Scotland to retain its support for the union. Labour had joined the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats to promise further devolution of powers to the Scottish parliament and also the preservation of a controversial formula for allocating U.K. public spending that sees Scots do better per capita than their English counterparts. The morning after the referendum, Prime Minister Cameron raised the idea that these concessions to Scotland should be matched by greater local powers for the English, including “English Votes for English Laws” (the unfortunate acronym is EVEL), potentially barring MPs representing constituencies outside England from voting on matters affecting only English voters. It sounds fair enough but is constitutionally complex — and would probably deprive Labour, with its 41 Scotland-based MPs, of a working majority on key issues such as health and education.

In rejecting Cameron’s proposed breakneck schedule for EVEL, Miliband may well have put national interests ahead of party considerations. Rushed constitutional change is seldom a good idea. To voters, already disinclined to trust politicians, his response may well look like naked self-interest. He may be the most likely winner of the U.K.’s 2015 elections but Miliband, it seems, just can’t win and that’s why the Labour Party conference is such an odd, damp, dreary affair.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com