Domestic abuse of any kind is violent and ugly, and today there is rightful public outrage over it, whether the perpetrators are famous athletes, college students, members of the military, or leaders of our institutions and communities.

On Tuesday, I joined hundreds of domestic violence survivors and advocates at the National Archives to commemorate the 20th Anniversary of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) and to recognize a right that flows directly from our founding documents: the right of every woman in America to be free from violence and free from fear.

Twenty years ago, this was a right that few people understood and our culture failed to recognize. Kicking a wife in the stomach or pushing her down the stairs was repugnant, but it wasn’t taken seriously as a crime. It was considered a “family affair.” State authorities assumed if a woman was beaten or raped by her husband or someone she knew, she must have deserved it. It was a “lesser crime” to rape a woman if she was a “voluntary companion.” Many state murder laws still held on to the notion that if your wife left you and you killed her, she had provoked it and you had committed manslaughter.

That was the tragic history when, as chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, I introduced the Violence Against Women Act in 1990. We started out believing that the only way to change the culture was to expose the toll of domestic violence on American families. And I was convinced, as I am today, that the basic decency of the American people would demand change once they saw the scale of violence and the depth of the ignorance and stereotypes used to justify it.

To paint an honest picture, I invited health professionals to testify on the long-term psychological effects of the violence. Advocates told of the desperate need for funding for shelters and centers. But what broke through were the stories of courageous survivors.

One woman testified ten years after being raped by her boyfriend as a 15-year-old, “It is not the gory details that you need to hear to understand, it is the suffering, the loss of feeling any control, the incredible self-blame, and the disruption of a survivor’s life that can’t often be heard.” She asked the committee a powerful question: “How did I get this message that…it was my fault?”

We heard more stories through a report detailing a single week in America where 21,000 women were victims of assaults, murders, and rapes. Women had arms broken with hammers and heads beaten with pipes by men who supposedly loved them.

But as more women — and men — spoke out, minds began to change. Terms of the debate shifted. And we forged a national consensus that something had to be done. Local coalitions of shelters and rape crisis centers led the way. National women’s groups and civil rights groups got on board. Brave women judges and lawyers stood up to Chief Justice Rehnquist, who opposed to the bill because it included a civil rights remedy. To get it passed with that remedy and more resources for shelters and advocates, I added VAWA to a crime bill I had been working on for years that had bipartisan support, put 100,000 cops on the streets, and provided more assistance for law enforcement.

On September 13, 1994, President Clinton signed the bill into law, and with each reauthorization over the years we’ve improved and included more protections for women, LGBT Americans, and Native Americans.

As a consequence of the law, domestic violence rates have dropped 64%; billions of dollars have been averted in social and medical costs; and we’ve had higher rates of convictions for special-victims unites and fundamental reforms of state laws. The nation’s first National Domestic Violence Hotline has helped 3.4 million women and men fight back from domestic and dating violence.

And along the way we’ve changed the culture. Abuse is violent and ugly and today there is rightful public outrage over it. It matters that the American people have sent a clear message: you’re a coward for raising a hand to a woman or child—and you’re complicit if you fail to condemn it.

That’s a monumental change from twenty years ago, and it’s why the Violence Against Women Act is my proudest legislative accomplishment. But we know there’s more to do. One in five women in America has experienced rape or attempted rape. Sex bias still plagues our criminal justice system with stereotypes like “she deserved it” or “she wore a short skirt” tainting the prosecution of rape and assault.

But twenty years after this law first passed, I remain hopeful as ever that the decency of the American people will keep us moving forward in the fight against this rawest form of violence and a culture that hides it. They understand the true character of our country is measured when violence against women is no longer accepted as society’s secret and where we all understand that even one case is too many.

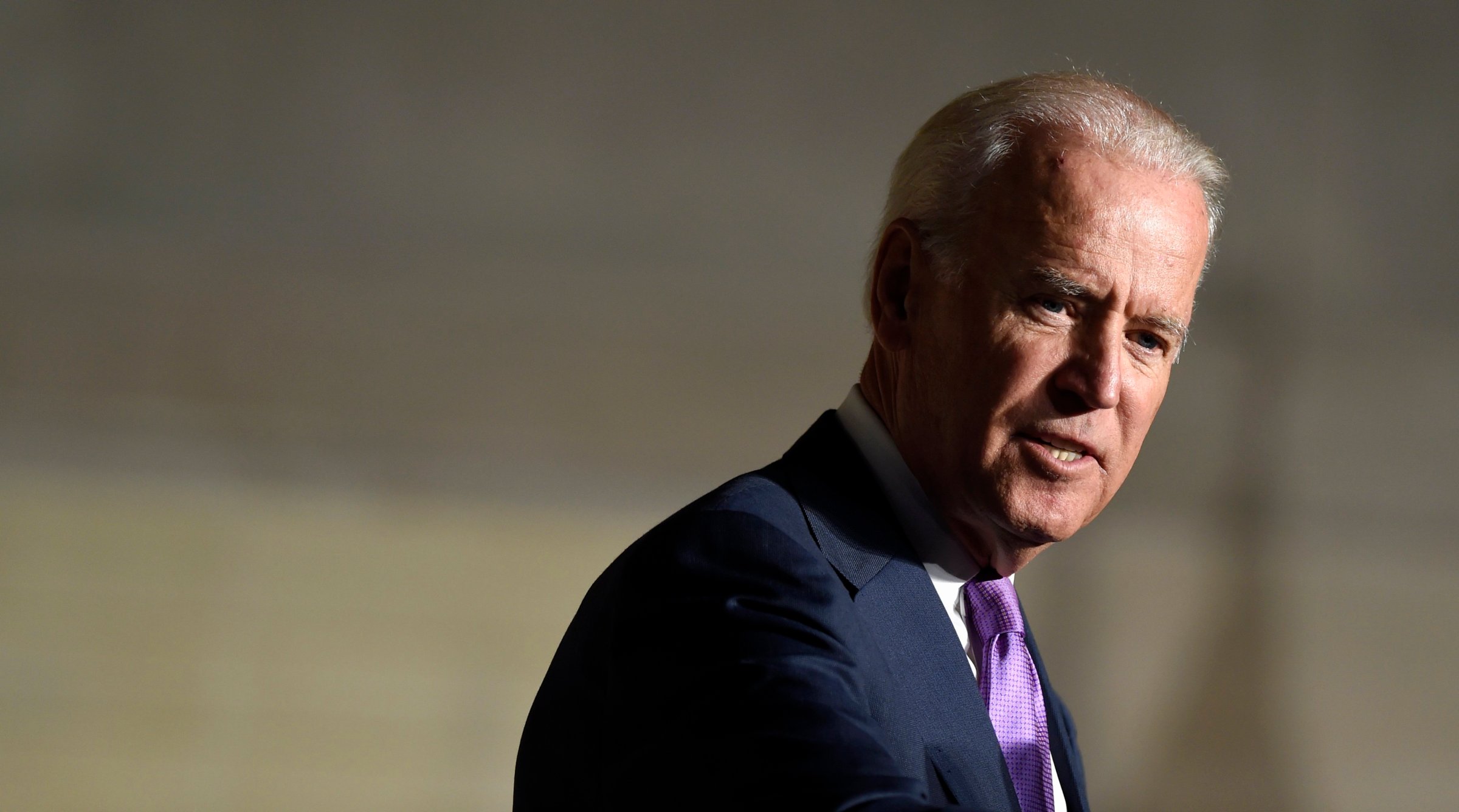

Joe Biden is the Vice President of the United States.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com