Exactly 200 years ago this weekend, on Sept. 14, 1814, Francis Scott Key, a lawyer from Georgetown, found himself on a ship in Baltimore’s harbor as the War of 1812 raged around him.

On Aug. 24, 1814, the British army had invaded Washington, D.C. The Capitol building and the White House were burned, and the Brits turned to nearby Baltimore, firing on the harbor’s Fort McHenry on Sept. 13. It was in the midst of that battle that Key, who had been negotiating for the release of a prisoner of war, was at sea. At dawn on Sept. 14, the American flag still flew over the fort; the British were in retreat. Key’s poem about what he saw, which he set to an earlier tune by John Stafford Smith, came to be known as “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

But Key hadn’t written the American national anthem. In fact, for more than a century after that day, America had no national anthem at all.

The “Star-Spangled Banner” did quickly gain popularity, however, and military bands during the Civil War and World War I used it as a de facto anthem — even though officially it was just another patriotic ditty like the rest. The effort to acquire a national anthem gained speed following World War I, as can be traced through early mentions of the song in TIME. In 1925, the magazine reprinted an anti-“Banner” letter from a man who found it “hurtful to every ideal which Americans cherish” in its violence (particularly toward Britain, an ally) and who said that he would refuse to remove his hat while the song was played. The other camp was represented by people like John C. Wright, whose 1929 letter to the magazine is shown above:

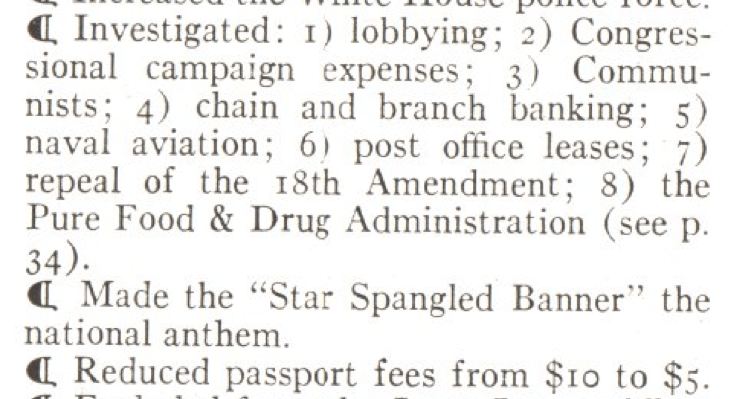

As Wright’s letter makes clear, one of the main concerns with naming “The Star-Spangled Banner” the anthem was that, with its octave-and-a-half range, it was just too hard to sing. That was why, in Feb. 1930, the pro-“Banner” crowd invited the U.S. Navy Band to perform the song for the House Judiciary Committee. “Two sopranos sang all its four verses to prove that its words were not difficult, that its pitch was not too high,” TIME reported. And, whether or not that was the deciding factor, it worked. In listing the work of the 1930 congressional session, TIME had this to report:

On Mar. 3, 1931, President Hoover signed the bill into law, and the U.S. had an anthem for the first time. But two sopranos do not a nation make — and history has shown that, despite its other virtues, the song isn’t exactly easy to sing. These ten terrible national anthem renditions are proof enough of that.

Read a 1990 story on the difficulties of singing the national anthem here, in TIME’s archives: Oh Say, Can You Sing It?

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com