Militant. Radical. Man-hating. If you study word patterns in media over the past two decades, you’ll find that these are among the most common terms used to talk about the word “feminist.” Yes, I did this — with the help of a linguist and a tool called the Corpus of Contemporary American English, which is the world’s largest database of language.

I did a similar search on Twitter, with the help of Twitter’s data team, looking at language trends over the past 48 hours. There, the word patterns were more simple. Search “feminist,” and you’ll likely come up with just one word association: Beyoncé.

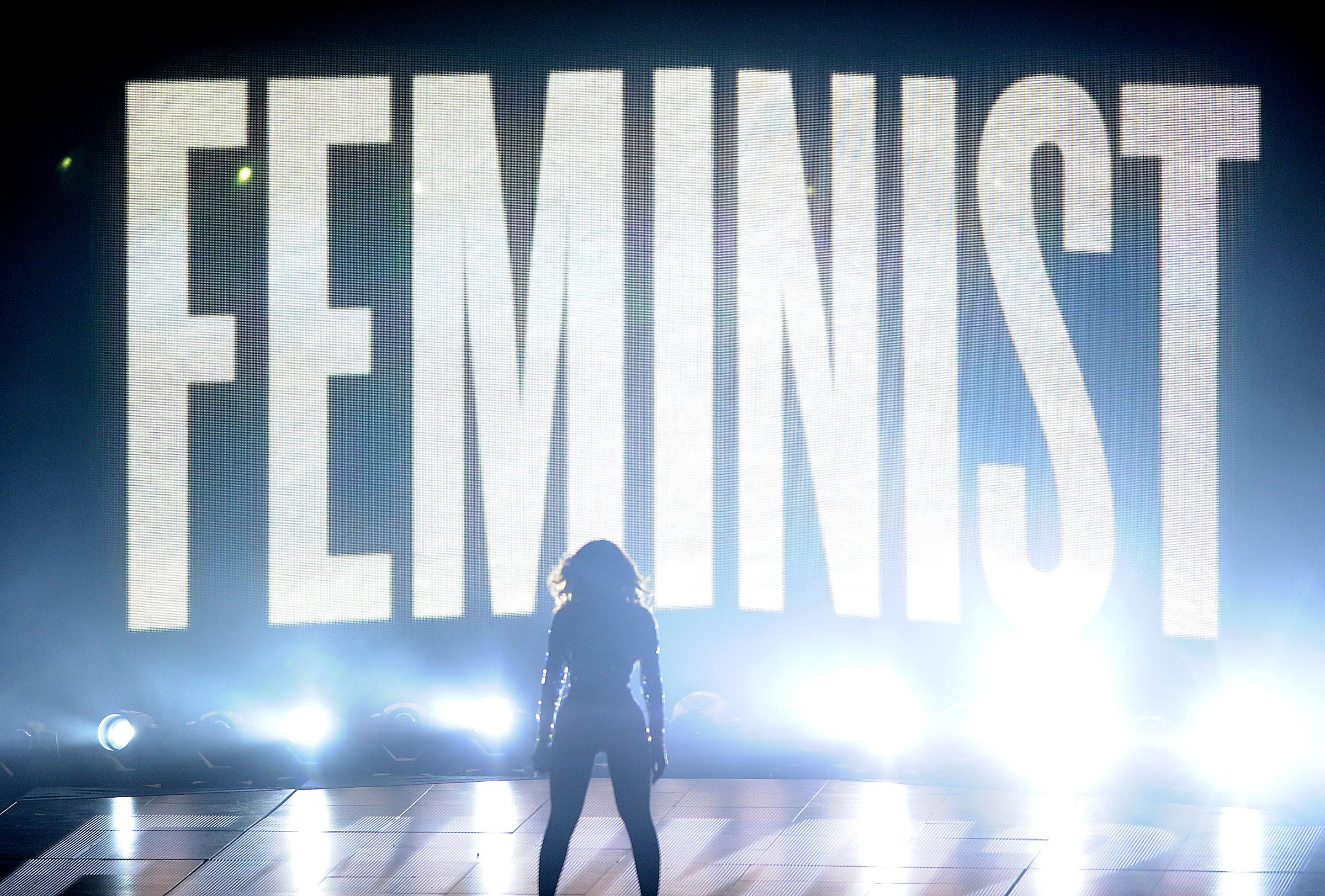

That’s a product of Sunday’s MTV Video Music Awards, of course, in which the 33-year-old closed out the show with an epic declaration of the F-Word, a giant “FEMINIST” sign blazing from behind her silhouette.

As far as feminist endorsements are concerned, this was the holy grail: A word with a complicated history reclaimed by the most powerful celebrity in the world. And then she projected it — along with its definition, by the Nigerian feminist author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie — into the homes of 12 million unassuming Americans. Beyoncé would become the subject of two-thirds of all tweets about feminism in the 24 hours after her appearance, according to a data analysis by Twitter, making Sunday the sixth-highest day for volume of conversation about feminism since Twitter began tracking this year (the top three were days during #YesAllWomen).

“What Bey just did for feminism, on national television, look, for better or worse, that reach is WAY more than anything we’ve seen,” the writer Roxane Gay, author of the new book, Bad Feminist, declared (on Twitter, naturally).

“HELL YES!” messaged Jennifer Pozner, a writer and media critic.

“It would have been unthinkable during my era,” said Barbara Berg, a historian and the author of Sexism in America.

Feminism may be enjoying a particular celebrity moment, but let’s just remember that this wasn’t always the case. Feminism’s definition may be simple — it is the social, political and economic equality of the sexes, as Adichie put it — and yet its interpretation is anything but. “There was only about two seconds in the history of the world in which women really welcomed [feminism],” Gail Collins, The New York Times columnist and author of America’s Women once told me in 2010, for an article I was writing about young women and feminism. “There’s something about the word that just drives people nuts.”

Over the past 40 years in particular, as Berg explains it, the word has seen it all: exultation, neutrality, uncertainty, animosity. “Feminazi” has become a perennial (and favorite) insult of the religious right (and of Rush Limbaugh). In 1992, in a public letter decrying a proposal for an equal rights amendment (the horror!) television evangelist Pat Robertson hilariously proclaimed that feminism would cause women to “leave their husbands, kill their children, practice witchcraft, destroy capitalism, and become lesbians.”

Even the leaders of the movement have debated whether the word should be abandoned (or rebranded). From feminist has evolved the words womanist, humanist, and a host of other options — including, at one point, the suggestion from Queen Bey herself for something a little bit more catchy, “like ‘bootylicious.'” (Thank God that didn’t stick.)

It wasn’t that the people behind these efforts (well, most of them anyway) didn’t believe in the tenets of feminism — to the contrary, they did. But there was just something about identifying with that word. For some, it was pure naiveté: We were raised post-Title IX, and there were moments here and there where we thought maybe we didn’t need it. (We could be whatever we wanted, right? That was the gift of the feminists who came before us.) But for others, it was a notion of what the word had come to represent: angry, extreme, unlikeable. As recently as last year, a poll by the Huffington Post/YouGov found that while 82 percent of Americans stated that they indeed believe women and men should be equals, only 20 percent of them were willing to identify as feminists.

Enter… Beyoncé. The new enlightened Beyoncé, that is. Universally loved, virtually unquestioned, and flawless, the 33-year-old entertainer seems to debunk every feminist stereotype you’ve ever heard. Beyoncé can’t be a man-hater – she’s got a man (right?). Her relationship – whatever you believe about the divorce rumors – has been elevated as a kind of model for egalitarian bliss: dual earners, adventurous sex life, supportive husband and an adorable child held up on stage by daddy while mommy worked. Beyoncé’s got the confidence of a superstar but the feminine touch of a mother. And, as a woman of color, she’s speaking to the masses – a powerful voice amid a movement that has a complicated history when it comes to inclusion.

No, you don’t have to like the way Beyoncé writhes around in that leotard – or the slickness with which her image is controlled – but whether you like it or not, she’s accomplished what feminists have long struggled to do: She’s reached the masses. She has, literally, brought feminism into the living rooms of 12.4 million Americans. “Sure, it’s just the VMAs,” says Pozner. “She’s not marching in Ferguson or staffing a battered woman’s shelter, but through her performance millions of mainstream music fans are being challenged to think about feminism as something powerful, important, and yes, attractive. And let’s head off at the pass any of the usual hand-wringing about her sexuality — Madonna never put the word FEMINIST in glowing lights during a national awards show performance. This is, as we say… a major moment.”

It’s what’s behind the word that matters, of course. Empty branding won’t change policy (and, yes, we need policy change). But there is power in language, too.

“Looking back on those early days of feminism, you can see that the word worked as a rallying cry,” says Deborah Tannen, aa linguist at Georgetown University and the author of You Just Don’t Understand, about men and women in conversation. “It gave women who embraced [it] a sense of identity and community — a feeling that they were part of something, and a connection to others who were a part of it too. Beyoncé’s taking back this word and identifying with it is huge.”

Bennett is a contributing columnist at TIME.com covering the intersection of gender, sexuality, business and pop culture. A former Newsweek senior writer and executive editor of Tumblr, she is a contributing editor for Sheryl Sandberg’s women’s foundation, Lean In. You can follow her @jess7bennett.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com