The photographs and videos of police trying to calm the rioting in Ferguson, Mo., look like a war zone. There’s the black-clad special-ops cops, backed by armored tactical vehicles that wouldn’t look out of place on a battlefield. The police are doing their best to restore order following Saturday’s police killing of unarmed Michael Brown, 18. But their tools and tactics have grabbed the attention of some of the nation’s real soldiers dispatched to fight its post-9/11 wars.

Brandon Friedman, who served as an Army officer with the 101st Airborne in Afghanistan and Iraq, tweeted a pair of photographs contrasting a policeman in Ferguson with one of him on the eve of the 2003 Iraq invasion. “The gentleman on the left,” he said of the Missouri cop Wednesday, “has more personal body armor and weaponry than I did while invading Iraq.”

“Army underequipped pros,” a commenter said. “Cops here overeq/amateurs.”

Actually, that’s not right. Local police departments are strapped for cash and can’t afford the high-tech body armor, communications gear, weapons and armored vehicles that have replaced the local cop’s nightstick, revolver and cruiser. Most of this beefed-up arsenal is coming from the world’s biggest Army-Navy surplus store: the Pentagon.

The scenes from Ferguson have reached a point where Mashable has posted photos from Afghanistan, Iraq, and Ferguson—and asked readers to try to figure out where they’re from. The Department of Defense told USA Today last year that Ferguson acquired two Humvees, a 10-kilowatt generator and an empty flatbed trailer. St. Louis County, whose police have been out in force in Ferguson, acquired much more equipment, according to the Missouri Department of Public Safety, including night vision goggles, Humvees and more.

With the Mine-Resistant, Ambush-Protected vehicles, Kevlar-vested and helmeted personnel, outfitted with serious-looking firepower, in some snapshots it’s tough to tell Ferguson from Firdos Square in Baghdad or Farah, Afghanistan.

To be sure, there are times when a law-enforcement challenge—rescuing hostages or taking down terrorists—requires such heavy-duty gear, including some military handdowns. But the use of SWAT—Special Weapons and Tactics— teams has leapfrogged from such serious cases to less-serious episodes of trying to calm civil unrest, where a less-confrontational approach might work better.

“American policing has become unnecessarily and dangerously militarized, in large part through federal programs that have armed state and local law enforcement agencies with the weapons and tactics of war, with almost no public discussion or oversight,” the American Civil Liberties Union reported in June. “The use of hyper-aggressive tools and tactics results in tragedy for civilians and police officers, escalates the risk of needless violence, destroys property, and undermines individual liberties.”

The Pentagon encourages the trend. Beginning with its effort to help fight the war on illegal drugs in 1997, the Defense Department’s provision of military gear to local police departments exploded following 9/11. “Since its inception, the [Law Enforcement Support Office] program has transferred more than $4.3 billion worth of property,” LESO says on its website. “In 2013 alone, $449,309,003.71 worth of property was transferred to law enforcement.” (Seventy-one cents?)

There’s a bit of a sales pitch, too: “If your law enforcement agency chooses to participate, it may become one of the more than 8,000 participating agencies to increase its capabilities, expand its patrol coverage, reduce response times, and save the American taxpayer’s investment,” it adds, along with a proviso noting that the weapons “are on loan from the DOD and remain the property of the DOD. … Trading, bartering or selling of the weapons is strictly prohibited.”

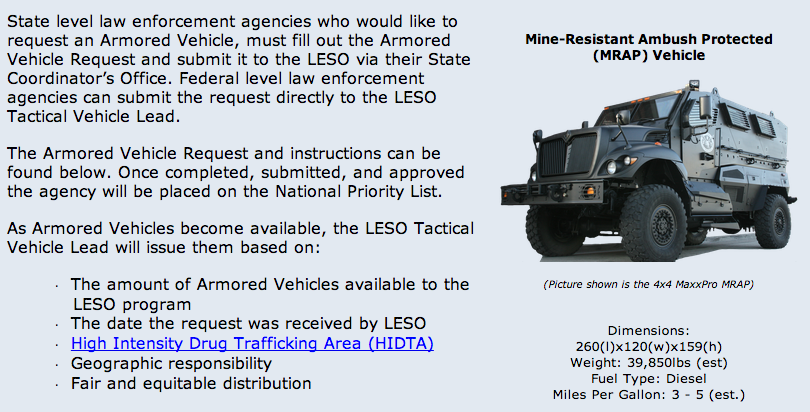

In 2011 and 2012, the ACLU estimated that an 63 police departments received 500 Mine-Resistant Ambush-Protected vehicles, armored 20-ton behemoths (3-5 mpg) that were designed to defeat enemy roadside bombs in Afghanistan and Iraq. The New York Times reported in June that the Pentagon has given local police forces 435 other armored vehicles, 533 aircraft and nearly 94,000 machine guns.

This has at least a few cops wondering what’s going on. “We’re not the military,” Salt Lake City Police Chief Chris Burbank has said. “Nor should we look like an invading force coming in.”

An ex-Boston police lieutenant—from a force not known for its gentler, kinder demeanor—agrees. “Have no doubt, police in the United States are militarizing, and in many communities, particularly those of color, the message is being received loud and clear: ‘You are the enemy,’” Tom Nolan, who spent 27 years on the Beantown beat, wrote for Defense One in June. “Police officers are increasingly arming themselves with military-grade equipment such as assault rifles, flashbang grenades, and Mine Resistant Ambush Protected, or MRAP, vehicles and dressing up in commando gear before using battering rams to burst into the homes of people who have not been charged with a crime.”

The ACLU said its analysis showed that 79% of SWAT missions were for drug investigations, while 7% were for hostage or barricade situations. It also noted that more than half of the SWAT deployments tracked were aimed at minorities. “The incidents we studied,” it added, “revealed stark, often extreme, racial disparities in the use of SWAT locally, especially in cases involving search warrants.”

We’ve been through similar, if not precise, episodes before: Think of the Ohio National Guard killing four students with their M1 Garand rifles at Kent State University in Ohio in 1970, for example. The troops turned on the students after some lobbed rocks and tear-gas canisters toward them. A presidential commission refrained from concluding why the Guardsmen fired the estimated 67 shots, but concluded that “the indiscriminate firing of rifles into a crowd of students and the deaths that followed were unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable.”

Of course, they were military troops. In Ferguson, those now wielding them are local law-enforcement officers, many of whom lack the training—and the command and control of their use—that most military units receive.

-Additional reporting by Josh Sanburn

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com