Correction appended, Aug. 12, 2014

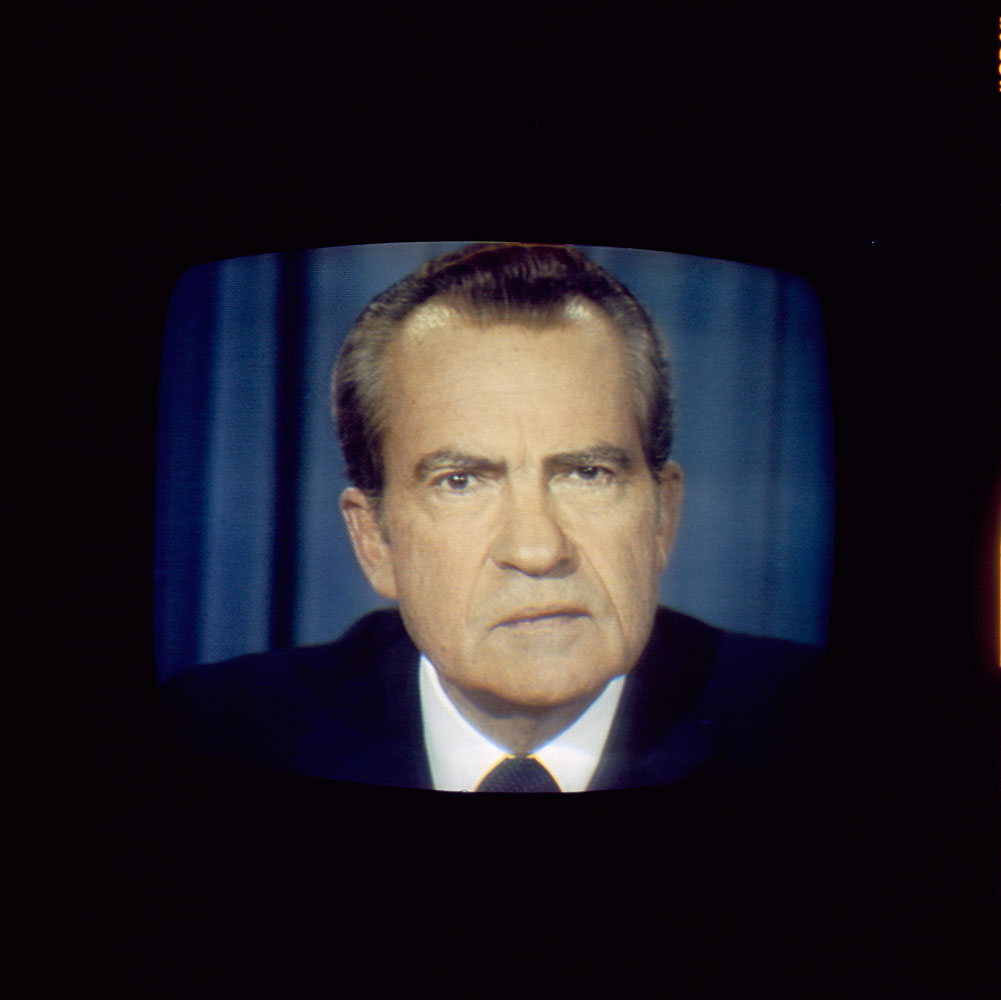

In the minutes before his 37th speech from the Oval Office, the 37th President of the United States bantered nervously with the CBS camera crew. He ran a sound check of the first words of his text (“My fellow Americans”) and made a joke about White House photographer Fred J. Maroon—”I’m afraid he’ll catch me pickin’ my nose.” After delivering the 3 min. 40 sec. address on national TV, he rose from his desk and, as he walked out, told the crew, “Have a merry Christmas, fellas.”

In August.

Forty years ago today, Richard Nixon became the first U.S. President to resign from office. He had been re-elected to serve four more years in 1972, with the slogan “Now more than ever.” In his victory over George McGovern, he received more votes than any other President in history. But faced with impeachment by the House of Representatives over the Watergate scandal, Nixon announced his resignation in that Thursday-night speech. At noon the following day, Aug. 9, 1974, he raised his hands flashing inappropriate and pathetic double-victory signs and helicoptered off the White House lawn to Andrews Air Force Base, from which he made his final trip on Air Force One to his San Clemente redoubt.

Gerald Ford, who then became President, spoke to the nation: “My fellow Americans, our long national nightmare is over.”

(WATCH: Harry Shearer’s re-enactment of Richard Nixon preparing for his resignation speech)

Many Americans then and since thought of Nixon’s 5 1/2-year reign as a long national nightmare. When the disgraced Chief Executive died in 1994, historian Jonathan Rauch wrote in the New Republic that Nixon’s had been “the worst presidency of the century.” Inheriting the Vietnam morass from Lyndon Johnson, Nixon promised to “end the war and win the peace,” yet he extended U.S. and allied military action into Cambodia, resulting in a half-million Southeast Asian deaths and 15,000 extra names on the Vietnam Memorial. Paranoid and prejudiced, he ordered his minions to spy illegally on his perceived enemies, who were many. He did not know in advance of the June 1972 break-in of the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate Hotel, but he approved its cover-up and lied about the conspiracy. Tapes of these conversations, which he had made for posterity, led to his downfall. Nixon resigned because he bugged himself.

Nixon’s shifty eyes and perpetual 5 o’clock shadow made him a natural fit for caricatured villainy. According to the Internet Movie Database, he has been impersonated in more than 80 films and television shows, from Dan Aykroyd’s Nixon (with John Belushi’s Henry Kissinger) on Saturday Night Live to the double-barreled blast in 2008: Frank Langella in Frost/Nixon and Josh Brolin in Oliver Stone’s biopic. For many Nixon haters, he is the character Rip Torn excoriated in Blind Ambition, or the mad wailer incarnated by Philip Baker Hall in Robert Altman’s Secret Honor. In the decade after his resignation, when those portrayals took hold, until today, the very mention of Nixon can cause splenetic outbursts from liberals who lived through his long career.

(READ: Richard Corliss on Richard Nixon and Frost/Nixon)

Even those who might sympathize with Nixon have to acknowledge that the man was no natural performer. In fact, he was one of a surprisingly high number of presidential aspirants who rose in the first era of TV but seemed incapable of selling their No. 1 product: themselves. Dwight Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan, Jack Kennedy, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama and, in his faux-cowboy fashion, George W. Bush could make the sale; Adlai Stevenson, Hubert Humphrey, George H.W. Bush, Bob Dole, Al Gore, John Kerry, John McCain and Mitt Romney could not, because they rarely gave the impression they were comfortable in their own skin. Nixon, with his mellifluous baritone, was a great politician for radio but creepy on TV.

He gave his opponents plenty of reasons to put him on their own enemy lists, beginning with his first run for Congress in 1946, when he daubed his rival, Helen Gahagan Douglas, with red smears. He teamed with Senator Joe McCarthy in exposing, or inventing, communist spies in the U.S. government. A charge of financial improprieties nearly lost Nixon his spot as Eisenhower’s running mate in the 1952 presidential election, until he took to the airwaves with his Checkers speech, declaring that he would not return the gift of a little dog that his daughters loved. Narrowly defeated by Kennedy in the 1960 presidential race, Nixon then ran for California governor, losing to the incumbent, Pat Brown, and later declaring to the press, “You won’t have Nixon to kick around anymore.”

That was Tricky Dick: mean winner, sore loser.

People kept kicking him around for decades. He eventually found surprising allies among what was left of the American left. Noam Chomsky, of whom few are leftier, called Nixon “the last liberal American President.” Sometimes goaded by large Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress, but often initiating the proposals, Nixon signed bills to create the Consumer Product Safety Commission, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration for workers’ injury claims and Title IX (sponsored by Democratic Senator Birch Bayh), which subsidized women’s sports programs. He fought for affirmative-action hiring policies and approved legislation that enabled injured workers under 65 to receive Medicare.

(READ: Why Noam Chomsky thinks Richard Nixon was the last liberal American President)

Nixon nominated four Justices to the Supreme Court, all of whom Congress approved, and three of whom voted with the 7-2 majority in the Roe v. Wade decision allowing abortions. Nixon appointee Harry Blackmun wrote the majority opinion, about which the President made no public declaration. (If he had appointed four pro-lifers to the court, the judgment would not have passed.) Nixon also instituted cost-of-living adjustments to Social Security and pushed for a comprehensive health care program, to be financed through then new HMOs. His negotiations with Senator Ted Kennedy foundered when Kennedy pushed for a single-payer plan. The Nixon version, with a few wrinkles, passed in 2010 as the Affordable Care Act.

Last Monday, Stephen Colbert devoted an entire episode of his show to assessing the legacy of a man he described as “my all-time favorite non-Reagan President, non-Cheney Vice President and non-Oats Quaker.” Colbert noted that Nixon “founded the EPA, ended school segregation, lowered the voting age to 18 and endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment. But his greatest achievement was restoring diplomatic relations with China, for which we owe Nixon a lasting debt, and China $1.3 trillion.” This is mostly true. Nixon did sign the 26th Amendment, which allowed 18-year-olds to vote, “despite my misgivings about the constitutionality of this one provision.” He met communist leader Mao Zedong to launch a détente as trade partners. He signed an Executive Order to establish the Environmental Protection Agency, endorsed Congress’s passage of the ERA for women and, over the objections of Vice President Spiro Agnew, enforced school desegregation.

(SEE: The Colbert Report episode on Richard Nixon)

Re-revisionists like Erik Loomis argue that “Richard Nixon was a liberal in no way … Nixon didn’t like signing those bills. He would have LOVED to rule in the 1980s when he could slash the welfare state, kill Central American commies, ignore the AIDS crisis, and undermine environmental regulations. But he couldn’t do that between 1969 and 1974 … As it was, he wanted to build support for the war by signing relatively liberal legislation.” Whatever Nixon, or today’s conservatives, might have loved to do, he did what he did. And instead of vilifying liberals, whom he may have deeply opposed and irrationally feared, he would quote Franklin Roosevelt’s definition—”It is a wonderful definition, and I agree with him”—that “a liberal is a man who wants to build bridges over the chasms that separate humanity from a better life.”

By any definition, Nixon and the Congress achieved a spectacular liberal domestic agenda between 1969 and 1974. “The War President” was really Lyndon Johnson: the Next Generation, lowering defense spending and pushing Johnson’s commitment to the Great Society. During Nixon’s presidency, the government slashed its defense budget’s share of the GDP by more than 50% and raised social-welfare programs by two-thirds; as Rauch notes, “this was a staggering change to have made in only six years.” Food-stamp benefits, welfare assistance, the minimum wage: they all went up under Nixon.

(READ: Jonathan Rauch on “the worst presidency of the century”)

In part, they went up because, for half a century, from Roosevelt to Jimmy Carter, the flow of federal entitlements was essentially progressive. Poor and working-class citizens got more assistance, and by 1975 the richest Americans—the top half of the wealthiest 1%—reached the lowest proportion of the GDP in the past 100 years. That drift shifted in the 1980s under Reagan, who put skids on New Deal, Fair Deal and Great Society legislation. Since then, the countercurrent has swelled to tidal-wave proportions. In 2008, as Obama and McCain vied for the presidency, political commentator Samuel Smith itemized Nixon’s agenda in an AlterNet story under this headline: “If Nixon Were Alive Today, He Would Be Far Too Liberal to Get Even the Democratic Nomination.”

Obamacare notwithstanding, the current President’s progressive instincts have been neutered by the rise of the Tea Party and Luddite conservatism. Speaker of the House John Boehner, when asked about his Congress’s reluctance to pass new laws, has said his mandate is to repeal the bad old ones—by which he means social programs. (We must not stand still; we must march boldly backward.) The top half of the 1%, and the corporations they run, have regained all their power and loot, plus some. The Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act. State assemblies manipulate laws to close legal abortion clinics. Citizens along the southern border tremble with rage at the influx of immigrants who would bolster our workforce in jobs that few Americans are willing to take. We are close to becoming the “pitiful, helpless giant” that Nixon described and denounced during the Vietnam War.

Forty years later, we can see Nixon as personally vindictive and socially generous, a small-minded man with a big-picture worldview. He wielded presidential power in ways both vicious and benevolent. Going against his conservative instincts, but perhaps listening to the Quaker voice from his youth, he endorsed progressive legislation that later Republicans have worked hard, largely successfully, to overturn. Liberals may hate themselves for thinking it, but they’d be tempted to honor Richard Nixon—now more than ever.

Correction: The original article misidentified the party of Indiana Senator Birch Bayh. He was a Democratic Senator. The article also misspelled the name of Helen Gahagan Douglas.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com