Space scientists have scrutinized comets with Earthly telescopes. They’ve watched from afar as one comet self-destructed and slammed into Jupiter, and as another committed hara kiri by venturing too close to the Sun. They’ve even sent space probes to whiz by comets at high speed, trying to unravel their still mysterious nature. Until now, however, nobody has attempted the daredevil stunt of inserting a space probe into orbit around a comet and following with the even riskier maneuver of sending a lander down to scratch and sniff at its ancient, murky surface.

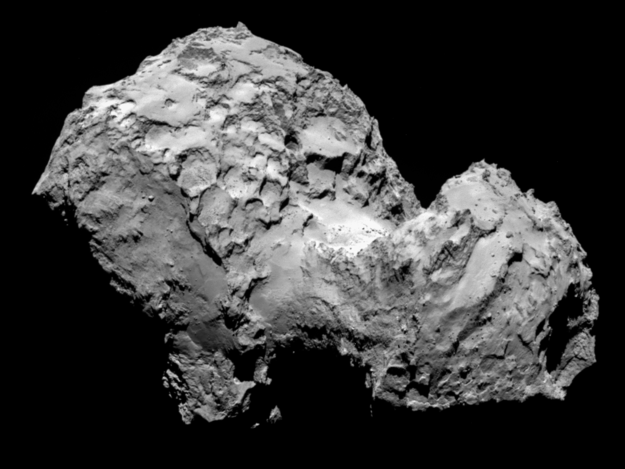

But that’s exactly what the scientists and engineers behind the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission have just accomplished—or the first part, anyway. On August 6 at about 7:00 A.M. ET, after more than ten years in pursuit, Rosetta caught up with and began circling a bulbous comet known as 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimernko (mercifully called 67P for short). And in early November, if all goes according to plan, the mother ship will deploy a lander named Philae to analyze the comet’s structure and composition in unprecedented detail.

It may seem like an awful lot of effort to expend just to study a member of a class of cosmic objects Harvard astronomer Fred Whipple once described as “dirty snowballs.” But these particular snowballs could be the key to all sorts scientific mysteries. They’ve been largely deep-frozen since the Solar System formed some 4.6 billion years ago, for example, so they preserve some of the original material from that seminal time. A rain of comets shortly after Earth came into existence might have been the source of our planet’s life-giving oceans. And some of that “dirt” comes in the form of tarry organic compounds, which means comet impacts could even have played a crucial role in the origin of life.

All of these questions, plus more nobody’s even thought to ask, could be answered, at least in part, by Rosetta and Philae as they ride along with 67P for the next 15 months, using a total of 21 separate instruments, including cameras to study the comet as it stirs to life in the heat of the Sun.

“We’ll be there through its closest approach with the Sun in summer 2015, when the activity is at a maximum and the nucleus is expelling thousands of pounds of material per minute,” says Mark Taylor, Rosetta’s chief scientist. That material will give 67P a temporary atmosphere for the orbiter to sample and analyze (among other things, it should be able to tell if the comet’s ice is a chemical match for Earth’s oceans), but since its closest approach to the Sun is still about 27 million miles (43 million km) outside Earth’s orbit, there’s not enough heat to make the thin atmosphere (called the coma) flare into a full-fledged tail.

The main spacecraft is currently circling at a distance of 60 miles (96 km) but it will gradually diminish to less than 10—stationkeeping while the lander does its work on the surface. That work will involve taking close-up photos and analyzing 67P’s surface chemistry—as well as the chemistry of the subsurface. Philae carries a handy drill which can penetrate a few inches into the ground beneath it. “It digs up a sample and puts it into a small oven,” explains Rosetta team member Fred Goesmann, of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Katlenburg-Lindau, Germany, which allows volatile chemicals to be released for chemical identification.

Another, ingenious experiment will be able to look far deeper into the comet’s interior. When the orbiter is on the opposite side of 67P from Philae’s landing site, it will send radio waves right through entire 3 mi. (4,8 km) mass of rock and ice. Philae will reflect the waves back—and just like a CT scan does with the human body—the reflected waves will reveal the interior structure of the comet. That will help scientists figure out whether it formed as a single piece, or as small chunks that slowly aggregated into 67P’s current size.

And that’s just a hint of what the mission is likely to uncover. Racing by comets at high speed or peering at them through telescopes has proven useful enough. Hanging out with one for more than a year of intensive study, however, will give scientists an unprecedented amount of information about these icy messengers from out beyond Neptune.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com