On the morning of July 30, in the ancient Silk Road city of Kashgar, an imam named Juma Tahir led prayers to mark Eid al-Fitr. Soon after, the 74-year-old was found stabbed to death outside his 600-year-old mosque. His murder capped days of violence in China’s vast and troubled northwest — and, many fear, augured conflict to come.

The territory that is today called Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region is, and has long been, contested space. The oasis towns that circle the Taklamakan Desert are claimed as both the homeland of the mostly Muslim, Turkic Uighur people, and, off and on for centuries, as Chinese land. With the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the ruling Communist Party sent forth waves of military personnel to settle the area. They have since been joined by migrants from the Chinese heartland, most but not all of whom, are from the ethnic Han majority; in 1949, Han people accounted for only about 6% of Xinjiang’s population; today, the figure is more than 40%.

The influx has left Xinjiang at odds. Beijing says integration with the rest of China is revitalizing the region, bringing money and jobs to the long-neglected west. Uighurs counter that they have yet to reap the benefits of the economic boom, and worry that their language, religion, and culture are threatened. Many want greater independence for the land they call East Turkestan. A small minority has fought for it, waging a decades-long insurgency that has mostly targeted local symbols of state power, including police stations, transportation hubs and government offices.

This year, the unrest moved east. In October 2013, an SUV driven by three members of a Uighur family plowed through crowds of holidaymakers in the heart of Beijing, killing five, including the occupants, at the northern end of Tiananmen Square. In March, a group of black-clad attackers stabbed and slashed their way through a train-station in Kunming, the capital of Yunnan province, killing 29. State media blamed the bloody ambush and two subsequent attacks in Xinjiang’s capital, Urumqi, on religious extremists.

The surge in violence prompted the government to tighten its grip on Xinjiang. Its town squares are now patrolled by police officers carrying automatic weapons. Across the Uighur heartland, villages are sealed by police checkpoints. Mistaking cultural practice for evidence of extremist thought, local governments are monitoring people’s habits and dress: there have been campaigns to stop students and civil students from fasting during the Muslim holy month; age restrictions on mosque visits; and, most recently, in Karamay, an ill-conceived move to ban women wearing veils and men sporting beards, from the city’s public buses.

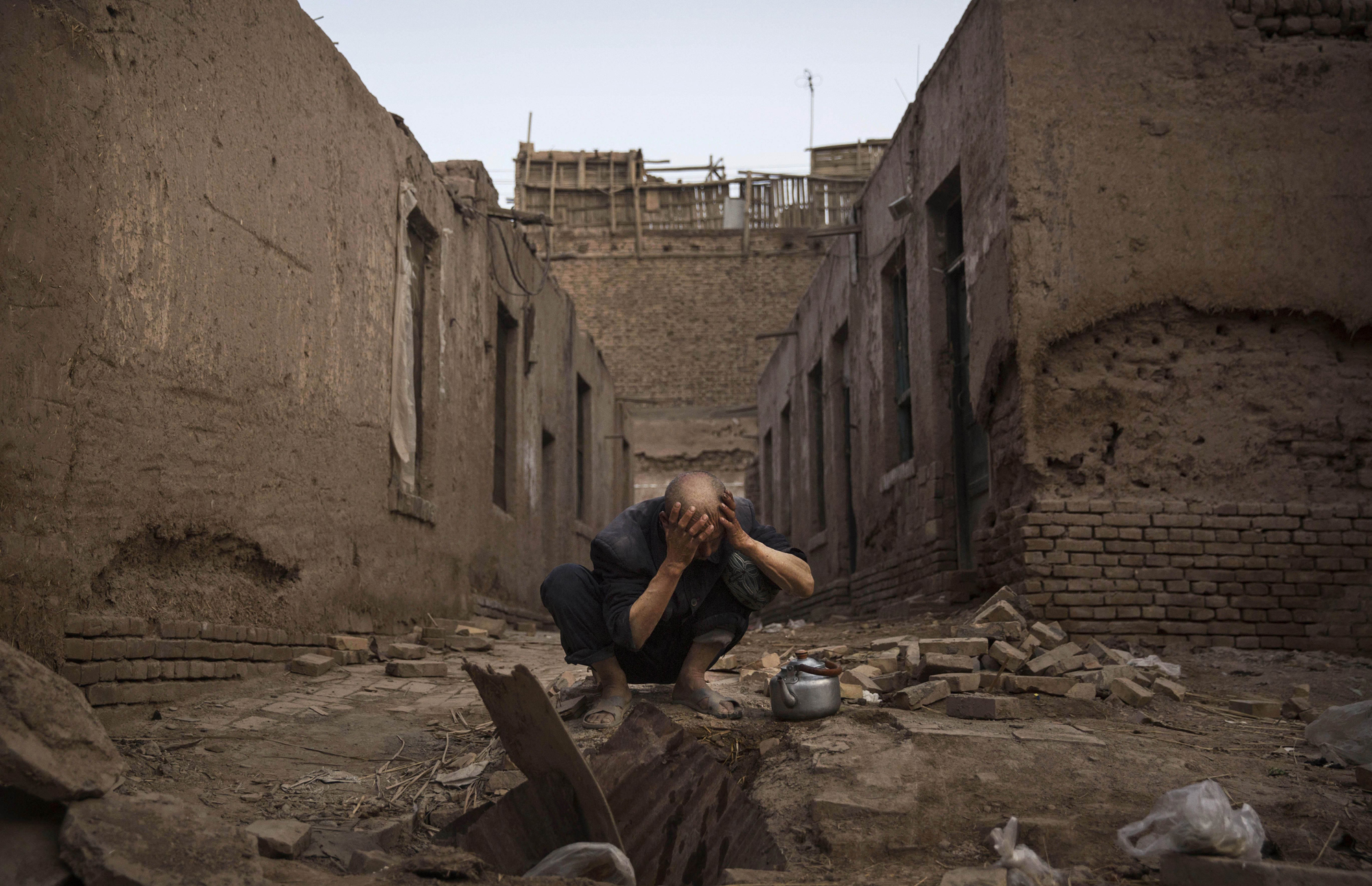

Kashgar, where Getty photographer Kevin Frayer made these pictures, is at the heart of all this. Sitting at the westernmost fringe of the People’s Republic, closer to Baghdad than Beijing, it has for centuries been a meeting point and trading hub, the place that connected Constantinople (now Istanbul) to Xi’an, before playing host to Britain and Russia’s spies during the 19th centuries “Great Game.” A good portion of the alleys and warrens they wrote home about have since been bulldozed; China will flatten 85% of the old city — an unpopular project that is well under way.

It was outside the city, in Kashgar prefecture, Shache county, that the most recent spate of bloodshed took root. What happened there on July 27 is still disputed and, because outside journalists are effectively barred from the area, facts are scarce. Chinese state media initially said “dozens” were killed. Later, they revised the official account, reporting that 96 people, including 37 civilians and 59 terrorists, died in a rampage masterminded by extremists. Their account is at odds with reporting by Radio Free Asia, a nonprofit news service, that linked the incident to state-led violence and suppression during Ramadan.

Days later, outside China’s largest mosque, imam Tahir was killed. China’s state newswire, Xinhua, reported his alleged assassins were “influenced by religious extremism” and plotted to “do something big” to increase their influence. Other nonstate outlets were quick to note, though, that Tahir was not just any imam, but a state-sanctioned one. He held a position in the government-run China Islamic Association and was often quoted backing the party line. Was that was got him killed?

That, like much else, remains unclear. But from wherever you stand, the murder feels like a grisly message: The lines are drawn; pick a side.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Emily Rauhala at emily_rauhala@timeasia.com