Updated: Thursday, July 31, 2014, 1:35 p.m.

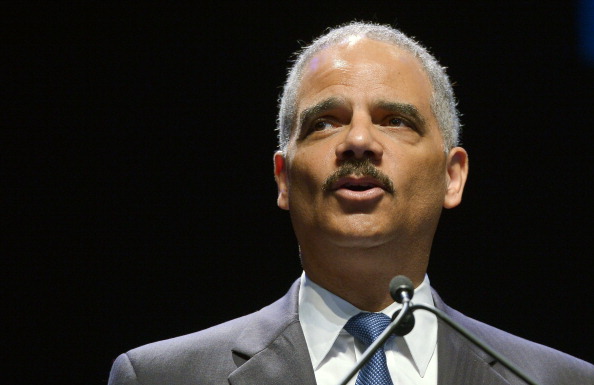

Citing concerns about equal justice in sentencing, Attorney General Eric Holder has decided to oppose certain statistical tools used in determining jail time, putting the Obama Administration at odds with a popular and increasingly effective method for managing prison populations. Holder laid out his position in an interview with TIME on Tuesday and will call for a review of the issue in his annual report to the U.S. Sentencing Commission Thursday, Justice department officials familiar with the report say.

Over the past 10 years, states have increasingly used large databases of information about criminals to identify dozens of risk factors associated with those who continue to commit crimes, like prior convictions, hostility to law enforcement and substance abuse. Those factors are then weighted and used to rank criminals as being a high, medium or low risk to offend again. Judges, corrections officials and parole officers in turn use those rankings to help determine how long a convict should spend in jail.

Holder says if such rankings are used broadly, they could have a disparate and adverse impact on the poor, on socially disadvantaged offenders, and on minorities. “I’m really concerned that this could lead us back to a place we don’t want to go,” Holder said on Tuesday.

Virtually every state has used such risk assessments to varying degrees over the past decade, and many have made them mandatory for sentencing and corrections as a way to reduce soaring prison populations, cut recidivism and save money. But the federal government has yet to require them for the more than 200,000 inmates in its prisons. Bipartisan legislation requiring risk assessments is moving through Congress and appears likely to reach the President’s desk for signature later this year.

Using background information like educational levels and employment history in the sentencing phase of a trial, Holder told TIME, will benefit “those on the white collar side who may have advanced degrees and who may have done greater societal harm — if you pull back a little bit — than somebody who has not completed a master’s degree, doesn’t have a law degree, is not a doctor.”

Holder says using static factors from a criminal’s background could perpetuate racial bias in a system that already delivers 20% longer sentences for young black men than for other offenders. Holder supports assessments that are based on behavioral risk factors that inmates can amend, like drug addiction or negative attitudes about the law. And he supports in-prison programs — or back-end assessments — as long as all convicts, including high-risk ones, get the chance to reduce their prison time.

But supporters of the broad use of data in criminal-justice reform — and there are many — say Holder’s approach won’t work. “If you wait until the back end, it becomes exponentially harder to solve the problem,” says former New Jersey attorney general Anne Milgram, who is now at the nonprofit Laura and John Arnold Foundation, where she is building risk-assessment tools for law enforcement. Some experts say that prior convictions and the age of first arrest are among the most powerful risk factors for reoffending and should be used to help accurately determine appropriate prison time.

And data-driven risk assessments are just part of the overall process of determining the lengths of time convicts spend in prison, supporters argue. Professor Edward Latessa, who consulted for Congress on the pending federal legislation and has produced broad studies showing the effectiveness of risk assessment in corrections, says concerns about disparity are overblown. “Bernie Madoff may score low risk, but we’re never letting him out,” Latessa says.

Another reason Holder may have a hard time persuading states of his concerns is that data-driven corrections have been good for the bottom line. Arkansas’s 2011 Public Safety Improvement Act, which requires risk assessments in corrections, is projected to help save the state $875 million through 2020, while similar reforms in Kentucky are projected to save it $422 million over 10 years, according to the Pew Center on the States. Rhode Island has seen its prison population drop 19% in the past five years, thanks in part to risk-assessment programs, according to the state’s director of corrections, A.T. Wall.

The spread of data analysis in criminal justice is a relatively new phenomenon: not long ago, reckoning a criminal’s debt to society was the work of men. For much of the 20th century judges, parole boards and probation officers made subjective decisions about when and whether a criminal was ready to return to society. Then in the 1970s and ’80s, as lawmakers sought to eradicate racial bias and accommodate victims’ rights, jail terms increasingly became a matter of a fixed formula set by law in a process that boiled down to the adage, “Do the crime, do the time.”

The result was a huge surge in prison populations, jail for low-risk offenders and often freedom for unrehabilitated inmates. The number of U.S. prisoners has risen 500% since 1980, to more than 2.2 million in 2012; 95% of them will be released at some point. Evidence collected everywhere from conservative Texas to liberal Vermont shows that statistical analysis used to rank prisoners according to their risk of recidivism can reduce prison populations and reduce repeat offending.

The federal Bureau of Prisons says it uses an assessment tool to gauge risk of misconduct among inmates and determine the security conditions under which they are held. Holder says he wants to ensure that the bills that are moving through Congress, which require broader use of assessments in federal prisons, account for potential social, economic and racial disparities in prison time. “Our hope would be to work with any of the Senators or Congressmen who are involved and who have introduced bills here so that we get to a place we ought to be,” Holder said.

— With reporting by Tessa Berenson and Maya Rhodan / Washington

The original version of this story has been updated to reflect comment from the federal Bureau of Prisons provided after publication

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com